Published online Aug 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i15.2103

Peer-review started: March 11, 2019

First decision: May 10, 2019

Revised: May 14, 2019

Accepted: June 26, 2019

Article in press: June 27, 2019

Published online: August 6, 2019

Processing time: 151 Days and 20.9 Hours

Venous thrombosis (VT) is one of the minor complications of pacemaker lead extraction. It is often found due to the swelling of the limbs after the extraction. It is easy to be neglected or even misdiagnosed in the absence of typical clinical symptoms. The incidence, risk factors, and long-term impact of this complication are still unclear. Herein, we report a case of deep VT caused by transvenous lead extraction, which is easily misdiagnosed.

A 66-year-old woman underwent a pacemaker lead extraction at our hospital because of a pacemaker pocket infection. After the extraction, she began to experience intermittent fever accompanied by sweating. The highest body temperature recorded was 37.9 °C. Additionally, she reported migratory pain that made her uncomfortable. The pain was mistakenly thought to be caused by operation trauma. At first, the pain radiated from the left chest to the mandible. Then, the pain in the left chest was alleviated, but pain in the left neck and throat appeared. Finally, the pain was confined to the mandible and a submandibular mass was palpated with no other abnormalities upon physical examination. Computed tomography venography and angiography finally indicated that the fever and pain were the symptoms of thrombophlebitis caused by lead extraction. The patient was then treated with rivaroxaban for more than three months and has shown no symptoms since she left the hospital.

The possibility of thrombosis should be considered when pain and recurrent fever occur after pacemaker lead extraction.

Core tip: Deep venous thrombosis caused by transvenous lead extraction is easily missed. The exact incidence is still unclear. Thrombosis after lead extraction during hospitalization should be identified early even without typical symptoms such as edema. Additionally, reasonable and standard anticoagulation therapy after lead extraction should be considered in the future.

- Citation: Wang SX, Bai J, Ma R, Lan RF, Zheng J, Xu W. Fever and neck pain after pacemaker lead extraction: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(15): 2103-2109

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i15/2103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i15.2103

With the increasing use of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs), increasing attention has been paid to the safety and complications of lead extraction after CIED implantation. The indications of transvenous lead extraction (TLE) include infection, venous stenosis and occlusion, lead malfunction, lead perforation, arrhythmias, as well as radiation therapy[1]. Complications of TLE include cardiac avulsion, vascular laceration, pericardial effusion, hemothorax, pulmonary embolism, pocket hematoma, venous thrombosis (VT), etc[1]. Among them, VT caused by TLE is easily missed in the clinic, and the incidence is unclear. The following case shows that VT can be caused by TLE and is characterized by intermittent fever and neck pain.

A 66-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital due to infection of the pacemaker pocket for one month.

The patient was diagnosed with sick sinus syndrome for which she received a dual-chamber pacemaker 10 years ago. One month prior to admission, after carrying a heavy burden, she found redness and swelling at the pocket site, which gradually ulcerated. The local hospital gave her an antiinfection treatment of cephalosporin for a week, but the outcome was not positive. Therefore, she was transferred to our hospital for further treatment.

The patient had a history of hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and chronic gastric ulcer. She underwent a meningioma resection 7 years earlier and cataract surgery in both eyes 8 years earlier. The patient had no history of hepatitis or tuberculosis.

The patient had no significant past history or family history.

The patient's blood pressure and blood glucose were well controlled by medication. Her body temperature was normal three days before the operation.

Except for swelling and ulceration at the pocket site, other physical examination results were normal. There were no abnormalities in the laboratory examination, electrocardiogram, chest X-ray, or preoperative echocardiogram. Multiple blood cultures were negative before the preventative use of vancomycin 0.5 g/q8h.

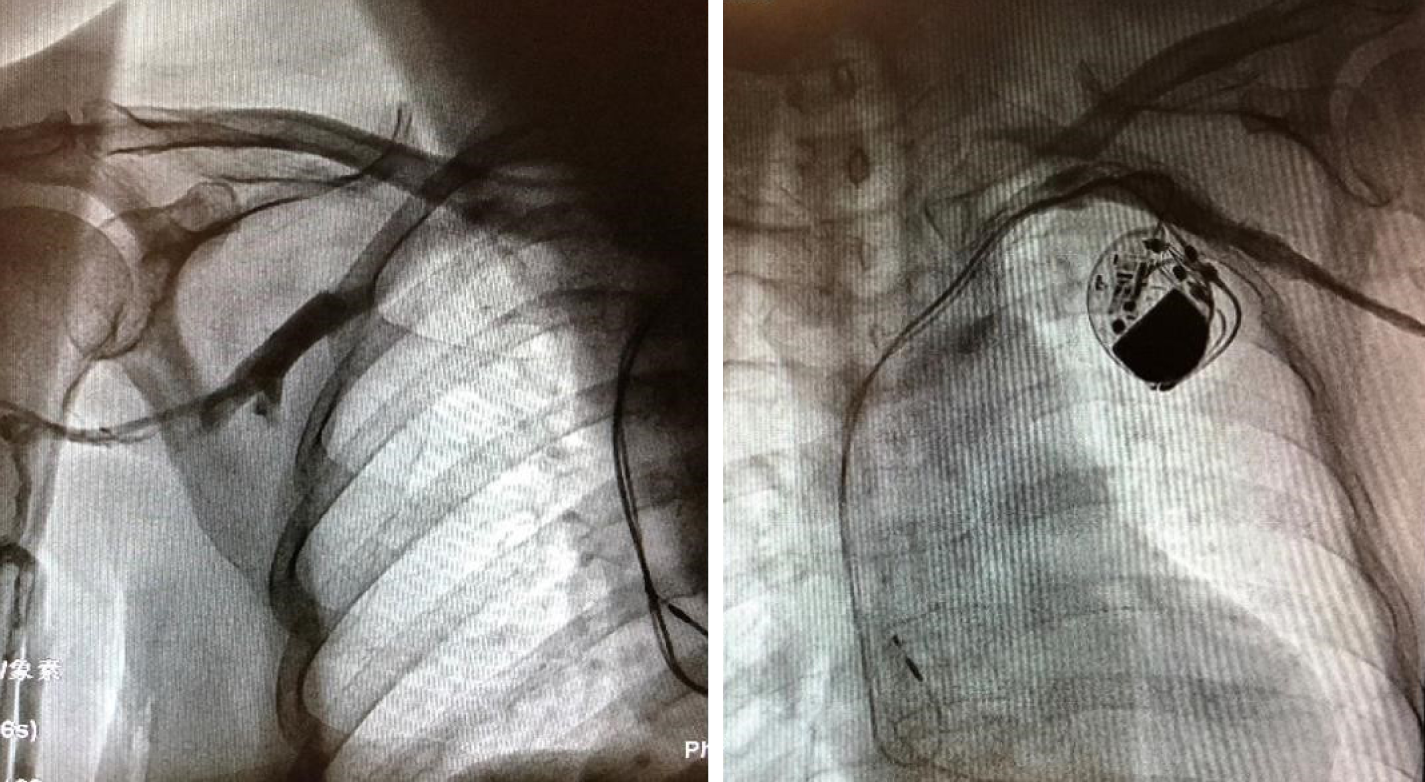

After excluding the contraindication of operation, the left leads were extracted successfully, and a temporary pacemaker was implanted on the other side. Intraoperative angiography revealed patency of the bilateral subclavian veins (Figure 1). The results of the pacemaker pocket tissue and lead culture showed the presence of Staphylococcus epidermidis, which is sensitive to vancomycin. Vancomycin was used continuously after the operation. The next day after the operation, the patient complained of pain radiating from the left chest to the mandible, with a pain score of 6. She began to present intermittent fever accompanied by sweating. Therefore, blood cultures were performed at that time; however, the results were negative. The serum concentration of vancomycin was up to standard. Three days after the operation, the patient felt that the pain in the left chest was alleviated, but increased pain in the left neck and throat accompanied by an irregular cough (dry cough, no sputum) appeared. Physical examination showed neck tenderness, normal tonsils, and a normal uvula. A few days later, the patient still had an intermittent low fever with sweating. Laboratory examination showed that routine blood and procalcitonin levels were normal, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was 44 mm/h, and the hypersensitive C-reactive protein (CRP) level was 45.6 mg/L. The operation incision and temporary pacemaker placement site were observed to be dry and clean without redness, burning, effusion, or pus. Seven days after the extraction, the patient felt relieved of pain in the left chest and neck and said that the pain was confined to the mandible. A submandibular mass was found through palpation. Routine blood tests, blood biochemical indexes, and procalcitonin levels were normal. Her ESR was 65 mm/h, hypersensitive CRP was 57.4 mg/L, plasma D-dimers was 9.58 mg/L, and fibrinogen was 5.6 g/L.

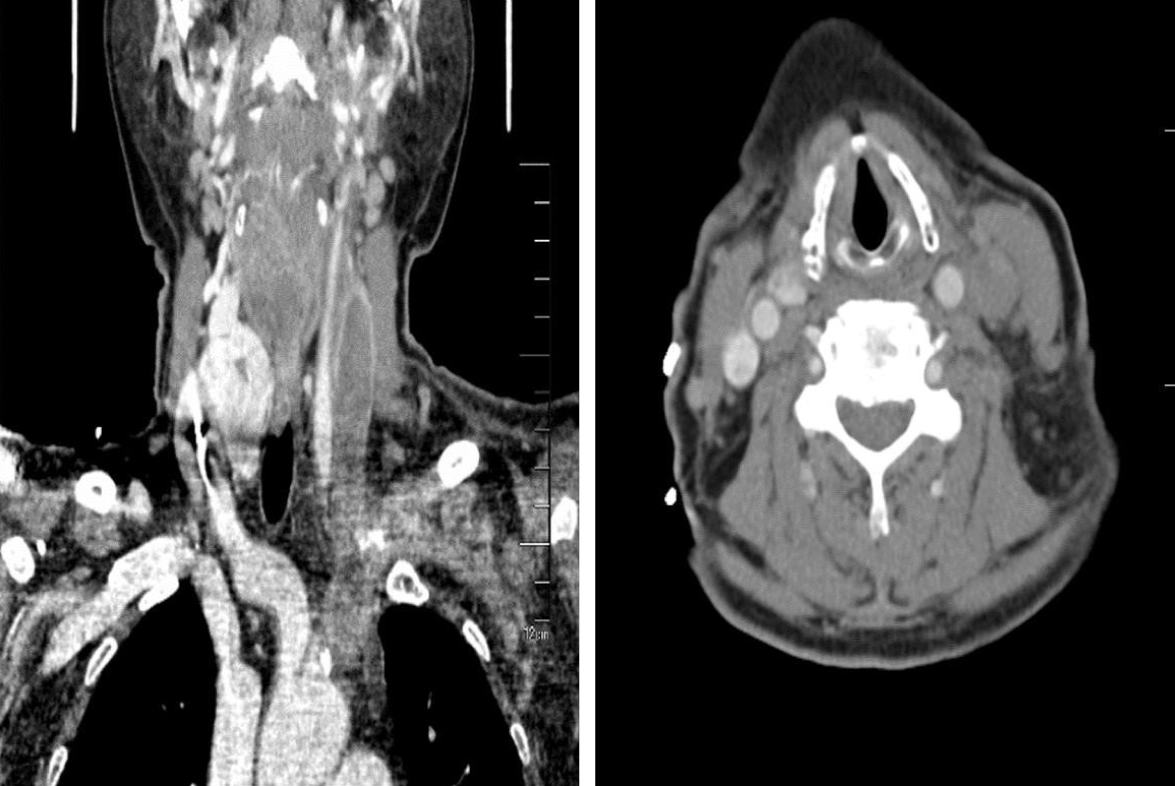

Color Doppler ultrasound showed left internal jugular vein thrombosis. Occlusion of the left common jugular vein, internal and external jugular veins, and subclavian vein was further demonstrated by computed tomography venography (CTV) (Figure 2). The patient refused the intravenous or subcutaneous use of anticoagulants; therefore, rivaroxaban was given.

VT after pacemaker lead extraction caused the symptoms of the patient.

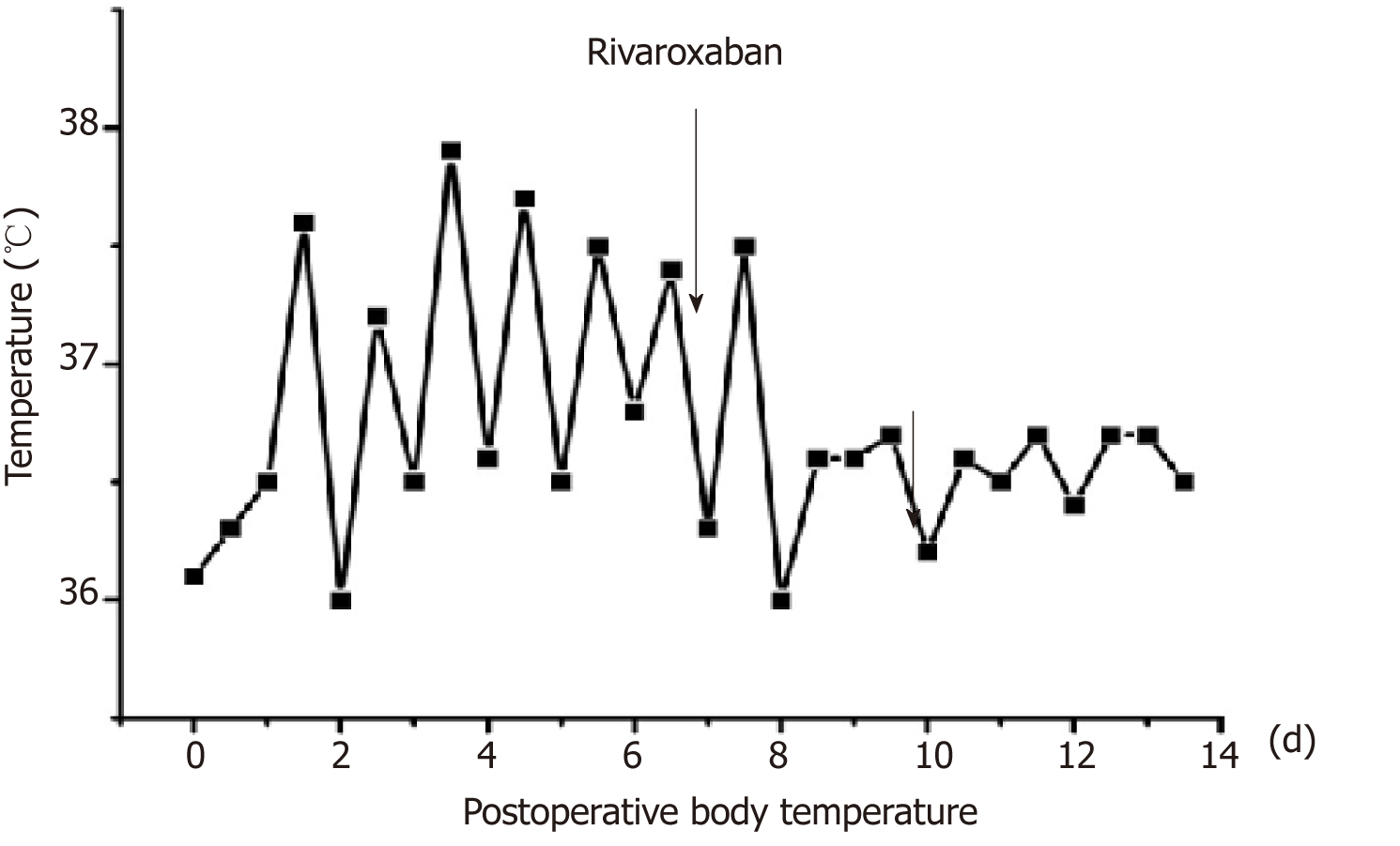

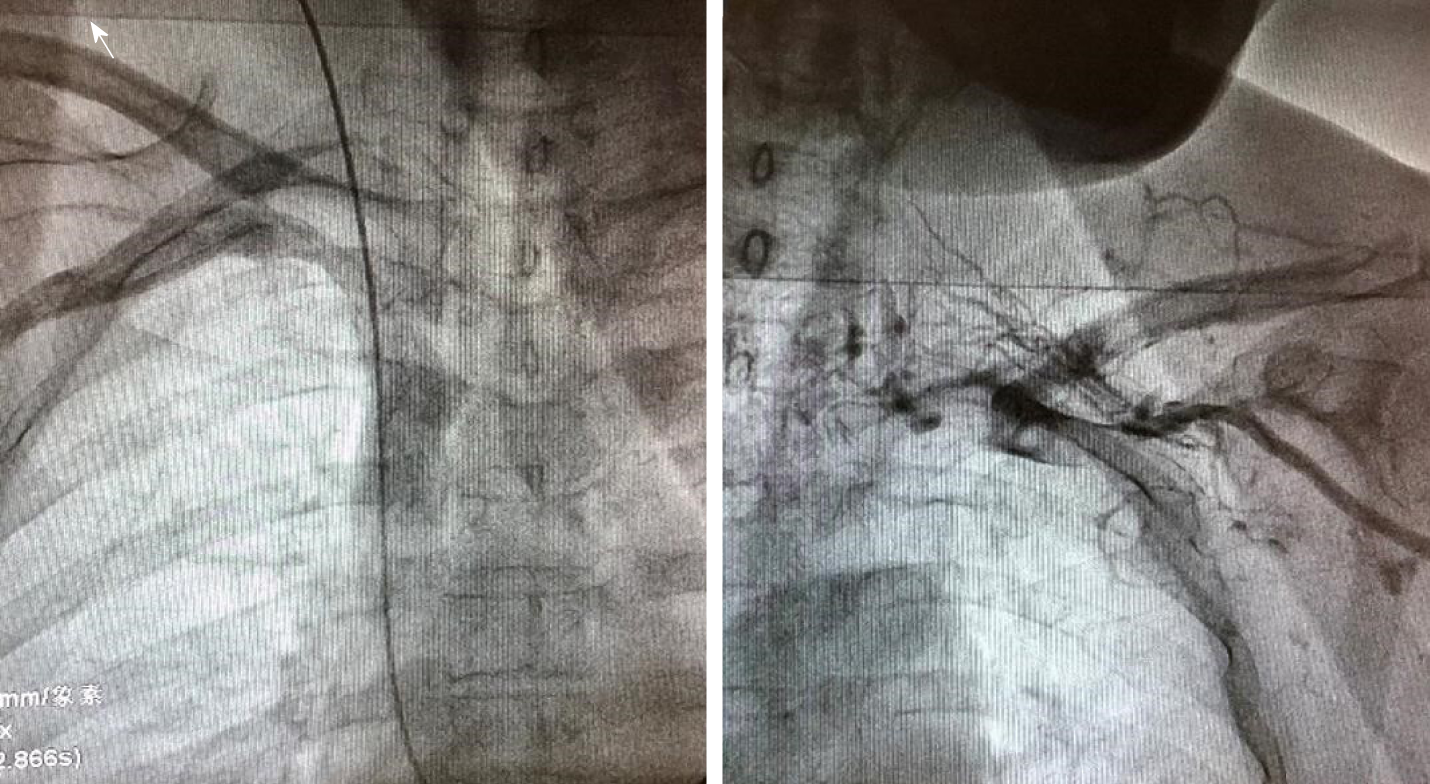

After 2 d of anticoagulant treatment with 15 mg rivaroxaban bid, the patient's temperature returned to normal (Figure 3), and no further neck pain was reported. Permanent pacemaker implantation on the right side was performed 5 d after anticoagulant therapy. Intraoperative angiography revealed occlusion of the left subclavian veins (Figure 4). Anticoagulant drugs were discontinued 24 h before implantation and were resumed 48 h after the operation.

Hypersensitive CRP and ESR showed a downward trend after anticoagulant therapy, and the patient was discharged from the hospital when her condition was stable. Clinical follow-up was conducted by telephone interviews with the patient. Rivaroxaban 15 mg bid was used for 21 d after the thrombosis was found, followed by 20 mg qd. The total rivaroxaban treatment lasted more than three months. The patient has shown no symptoms since she left the hospital.

Complications caused by TLE include major complications, minor complications, and death within 48 h after lead extraction[2]. Major complications are life-threatening or fatal complications, such as cardiac avulsion, vascular avulsion, stroke, and bleeding requiring transfusion. Minor complications include hematoma, hemothorax, VT and others that are not life-threatening to the human body. There has been a case report of thrombosis caused by TLE in the past. Hanninen et al[3] reported thrombosis extending from the right atrium to the right ventricular outflow after TLE, and the huge thrombus disappeared after anticoagulation treatment. The trauma of TLE might be the cause of thrombosis. Wazni et al[4] reported that the incidence of VT caused by TLE was 0.21%. A single-center study by Kennergren et al[5] found three patients with postoperative thrombosis in 647 patients, which indicated that the incidence was 0.5%. Wilkoff et al[6] studied TLE in 301 patients, and three of whom presented VT; therefore, the incidence was 1%. However, Bracke et al[7] indicated that the incidence of VT caused by TLE was more than 8%. In our center, bilateral venography was performed routinely before TLE and the implantation of a new pacemaker. Since 2013, we have conducted TLEs in 240 patients in our center. This patient was the first to suffer VT after TLE and before the implantation of a new pacemaker. However, we may have underestimated the incidence as we did not follow these patients after the new CIEDs were implanted. The exact incidence of this complication is unclear due to the different follow-up times of each researcher and the underestimation of atypical clinical symptoms caused by this complication. However, neglect of pulmonary embolism and other complications caused by deep VT might increase hospitalization rates and mortality[8].

Edema of the affected extremity is reported as the most typical symptom of upper-extremity deep VT[9]. Some patients may also suffer from pain or erythema, which occurs less often in upper-extremity deep VT[9]. Approximately 5% of deep VT patients are asymptomatic[9]. Similarly, edema is also a symptom with a prompting effect of VT caused by TLE[1,6,10]. CTV and venography can produce a definitive diagnosis.

Fever is reported to have the lowest predictive value of VT[11]. In our center, 82 of 240 patients had newly fever after TLE. Among them, 32 patients had a definite etiology: 13 were due to drug fever, 9 due to pulmonary infections, 5 to bacteremia, and 1 each to hyperthyroidism, cancer, gout, viral infection, and thrombophlebitis. In the remaining 50 people, we did not find a clear cause of fever and the average body temperature of them was lower than 38 °C. They might have suffered from physiological fever caused by operative trauma or neglected pathological fever[12].

The patient we reported lacked typical symptoms. We first considered that the fever that occurred after TLE was caused by infection because infection was the primary post-procedure complication of significance[1]. However, the results of laboratory tests did not support this diagnosis. We also considered that the patient might have a drug fever because previous literature reported that using vancomycin can lead to a drug fever in some patients[13]. However, this was ruled out because the body temperature returned to normal without the cessation of vancomycin. Additionally, we had no evidence to suspect that the fever was caused by tumors or autoimmune diseases because the related examinations were negative. The patient complained of neck pain. First, we only considered that the pain was caused by operation trauma and neglected that the pain might be caused by thrombophlebitis.

In retrospect, the patient had a pacemaker implanted for more than ten years, which might lead to severe adhesion between wire, tissue, and blood vessels. Therefore, thrombophlebitis occurred after the extraction of the leads, resulting in recurrent fever. After thrombosis of the left subclavian vein, it further spread to the left internal jugular vein. Therefore, her neck pain was related to thrombotic occlusion of the internal jugular vein. Venography indicated collateral circulation formation, so there was no swelling of the upper limbs or face. Postoperative fever prevented the implantation of the new pacemaker and prolonged her hospital stay. After anticoagulation treatment, her body temperature returned to normal. However, anticoagulation treatment might increase the risk of hematoma formation after pacemaker implantation[14]. Recent studies have shown that pocket hematoma increases the risk of device-related infection[15,16].

We hypothesize that the incidence of VT caused by TLE is higher than that reported previously in the literature. We might underestimate the incidence because of the lack of symptoms and short follow-up time. There are no clear guidelines regarding effective and safe anticoagulation strategies for patients with VT after TLE, especially in those who need new CIEDs implanted after TLE. As clinicians, we need to reduce misdiagnoses, and we should be alert to the possibility of VT when patients suffer from recurrent fever and neck pain after TLE.

We need pay more attention to the VT caused by pacemaker lead extraction, both in clinical work and in research fields.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Bloomfield DA, Karatza AA S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Kusumoto FM, Schoenfeld MH, Wilkoff BL, Berul CI, Birgersdotter-Green UM, Carrillo R, Cha YM, Clancy J, Deharo JC, Ellenbogen KA, Exner D, Hussein AA, Kennergren C, Krahn A, Lee R, Love CJ, Madden RA, Mazzetti HA, Moore JC, Parsonnet J, Patton KK, Rozner MA, Selzman KA, Shoda M, Srivathsan K, Strathmore NF, Swerdlow CD, Tompkins C, Wazni O. 2017 HRS expert consensus statement on cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead management and extraction. Heart Rhythm. 2017;14:e503-e551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 833] [Article Influence: 104.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Di Monaco A, Pelargonio G, Narducci ML, Manzoli L, Boccia S, Flacco ME, Capasso L, Barone L, Perna F, Bencardino G, Rio T, Leo M, Di Biase L, Santangeli P, Natale A, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F. Safety of transvenous lead extraction according to centre volume: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Europace. 2014;16:1496-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hanninen M, Cassagneau R, Manlucu J, Yee R. Extensive Thrombosis Following Lead Extraction: Further Justification for Routine Post-operative Anticoagulation. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2014;14:150-151. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Wazni O, Epstein LM, Carrillo RG, Love C, Adler SW, Riggio DW, Karim SS, Bashir J, Greenspon AJ, DiMarco JP, Cooper JM, Onufer JR, Ellenbogen KA, Kutalek SP, Dentry-Mabry S, Ervin CM, Wilkoff BL. Lead extraction in the contemporary setting: the LExICon study: an observational retrospective study of consecutive laser lead extractions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:579-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 446] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kennergren C, Bjurman C, Wiklund R, Gäbel J. A single-centre experience of over one thousand lead extractions. Europace. 2009;11:612-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wilkoff BL, Byrd CL, Love CJ, Hayes DL, Sellers TD, Schaerf R, Parsonnet V, Epstein LM, Sorrentino RA, Reiser C. Pacemaker lead extraction with the laser sheath: results of the pacing lead extraction with the excimer sheath (PLEXES) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33:1671-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bracke FA, Meijer A, Van Gelder LM. Symptomatic occlusion of the access vein after pacemaker or ICD lead extraction. Heart. 2003;89:1348-1349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Isma N, Svensson PJ, Gottsäter A, Lindblad B. Upper extremity deep venous thrombosis in the population-based Malmö thrombophilia study (MATS). Epidemiology, risk factors, recurrence risk, and mortality. Thromb Res. 2010;125:e335-e338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mai C, Hunt D. Upper-extremity deep venous thrombosis: a review. Am J Med. 2011;124:402-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Byrd CL, Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Sellers TD, Reiser C. Clinical study of the laser sheath for lead extraction: the total experience in the United States. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2002;25:804-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Diamond PT, Macciocchi SN. Predictive power of clinical symptoms in patients with presumptive deep venous thrombosis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1997;76:49-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Rehman T, deBoisblanc BP. Persistent fever in the ICU. Chest. 2014;145:158-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hung YP, Lee NY, Chang CM, Lee HC, Wu CJ, Chen PL, Lee CC, Chung CH, Ko WC. Tolerability of teicoplanin in 117 hospitalized adults with previous vancomycin-induced fever, rash, or neutropenia: a retrospective chart review. Clin Ther. 2009;31:1977-1986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chow V, Ranasinghe I, Lau J, Stowe H, Bannon P, Hendel N, Kritharides L. Peri-procedural anticoagulation and the incidence of haematoma formation after permanent pacemaker implantation in the elderly. Heart Lung Circ. 2010;19:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Essebag V, Verma A, Healey JS, Krahn AD, Kalfon E, Coutu B, Ayala-Paredes F, Tang AS, Sapp J, Sturmer M, Keren A, Wells GA, Birnie DH; BRUISE CONTROL Investigators. Clinically Significant Pocket Hematoma Increases Long-Term Risk of Device Infection: BRUISE CONTROL INFECTION Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1300-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Masiero S, Connolly SJ, Birnie D, Neuzner J, Hohnloser SH, Vinolas X, Kautzner J, O'Hara G, VanErven L, Gadler F, Wang J, Mabo P, Glikson M, Kutyifa V, Wright DJ, Essebag V, Healey JS; SIMPLE Investigators. Wound haematoma following defibrillator implantation: incidence and predictors in the Shockless Implant Evaluation (SIMPLE) trial. Europace. 2017;19:1002-1006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |