Published online Jul 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1892

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: June 12, 2019

Revised: June 16, 2019

Accepted: June 20, 2019

Article in press: June 21, 2019

Published online: July 26, 2019

Processing time: 110 Days and 11.4 Hours

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease of unknown aetiology. While it may affect any organ of the body, few cases of solitary lung involvement are published in the literature. Here, we report a rare case of pulmonary LCH (PLCH) in an adult.

A 52-year-old male presented to hospital in July 2018 with complaints of progressively worsening cough with sputum, breathlessness, easy fatigability, and loss of appetite since 2016, and a 32-year history of heavy cigarette smoking (average 30 cigarettes/d). Physical examination showed only weakened breathing sounds and wheezing during lung auscultation. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed irregular micronodules and multiple thin-walled small holes. Respiratory function tests showed a slight decrease. Ultrasonic cardiogram showed mild tricuspid regurgitation and no pulmonary hypertension. Fibreoptic bronchoscopy was performed with transbronchial biopsies from the basal segment of right lower lobe. LCH was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. The final diagnosis was PLCH without extra-pulmonary involvement. We suggested smoking cessation treatment. A 3-mo follow-up chest CT scan showed clear absorption of the nodule and thin-walled small holes. The symptoms of cough and phlegm had improved markedly and appetite had improved. There was no obvious dyspnoea.

Imaging manifestations of nodules, cavitating nodules, and thick-walled or thin-walled cysts prompted suspicion of PLCH and lung biopsy for diagnosis.

Core tip: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disorder of unknown aetiology and may affect any organ of the body. Local LCH only affects the lungs and is known as pulmonary LCH (PLCH). Reports of PLCH cases are relatively rare in the literature. This report describes the presentation, clinical investigation and diagnosis of a PLCH case involving a 52-year-old male with a 1-year history of progressively worsening cough with sputum, breathlessness, easy fatigability, and loss of appetite, and 32-yr history of heavy cigarette smoking. We also discuss the clinical presentation and signs, diagnosis, treatment, and outcome of such rare cases.

- Citation: Wang FF, Liu YS, Zhu WB, Liu YD, Chen Y. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(14): 1892-1898

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i14/1892.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1892

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disorder of unknown aetiology that is characterised by the infiltration of involved tissues by dendritic cells sharing phenotypic similarities with Langerhans cells, often which are organized into granulomas[1]. LCH lesions are comprised of cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and irregular nuclei with prominent folds and grooves. The characteristic immunophenotype includes expression of CD1A, S100, and langerin (CD207). The disease may affect patients of all ages, ranging from neonates to the elderly[2,3].

While LCH may affect any organ of the body, cases in children most frequently involve the bones (80% of cases), skin (33%), and pituitary gland (25%), followed by liver, spleen, hematopoietic system or lungs (15% each), lymph nodes (5%-10%), or the central nervous system (2%-4%, excluding the pituitary)[1]. Involvement of the so-called “risk organs” (i.e., liver, spleen, and haematopoietic system) is a well-established unfavourable prognosticator. The different clinical forms of LCH have been categorised into systemic and localised forms. Localised LCH often affects the bone, skin and lung, and is characterised by a good prognosis, with occasional spontaneous resolution[4].

Pulmonary LCH (PLCH) belongs to a group of rare pulmonary diseases. The prevalence of PLCH is unknown but may account for about 3%–5% of all adult diffuse lung diseases[5]. The precise prevalence of PLCH may be higher than estimated in earlier studies because it may be asymptomatic, remit spontaneously, and be difficult to identify in very advanced forms. In this article, we present a patient who underwent bronchoscopic biopsy to confirm PLCH.

A 52-year-old male was admitted to our department with a year-long history of cough with sputum and breathlessness.

The patient reported progressively worsening cough with sputum, breathlessness, easy fatigability, and loss of appetite since 2016.

The patient denied any other medical conditions.

The patient denied any family history of related diseases. He did however report heaving smoking for 32 years (30 cigarettes per day) and drinking liquor for 30 years (100 mL per day).

Physical examination showed stable vital signs, including blood pressure of 128/88 mmHg (normal range: 90-140/60-90 mmHg), pulse rate of 84/min (normal range: 60/min to 100/min), respiratory rate of 18/min (normal range: 16/min to 20/min), and temperature of 36.6 °C (normal range: 36.1 °C-37 °C). Weakened breathing sounds and wheezing were detected during lung auscultation.

The findings from standard laboratory tests were: arterial blood gas: FiO2: 21%, pH: 7.42, PCO2: 43 mmHg, PO2: 82 mmHg, SaO2: 96%, HCO3: 27.9 mmol/L, and buffer excess: 2.9 mmol/L; full blood count showed haemoglobin of 166 g/L (normal range: 130-175 g/L), white blood cell count of 11.8 × 109/L (normal range: 3.5 × 109/L to 9.5 × 109/L), neutrophil percentage of 70.9% (normal range: 40%-75%), lymphocyte count of 2.7 × 109/L (normal range: 1.1 × 109/L to 3.2 × 109/L), eosinophil count of 0.14 × 109/L (normal range: 0.02 × 109/L to 0.52 × 109/L), and platelet count of 395 × 109/L (normal range: 125 × 109/L to 350 × 109/L); and C-reactive protein content of 10.23 mg/L (normal range: 0 mg/L to 8 mg/L). Liver function, renal function, electrolytes, and thyroid function were normal.

Chest computed tomography (CT) at admission showed the texture to be increased and disordered, thickened bronchial wall, and diffuse patchy ground glass opacity, irregular micronodules and multiple thin-walled small holes in both lungs (Figure 1A and Figure 1B). There were no abnormalities in the skin and skeleton of the patient and no pituitary dysfunction and other related clinical manifestations were found in the patients. No abnormalities were found in head, neck and whole abdomen CT examination and suspicious of metastatic tumors in the liver.

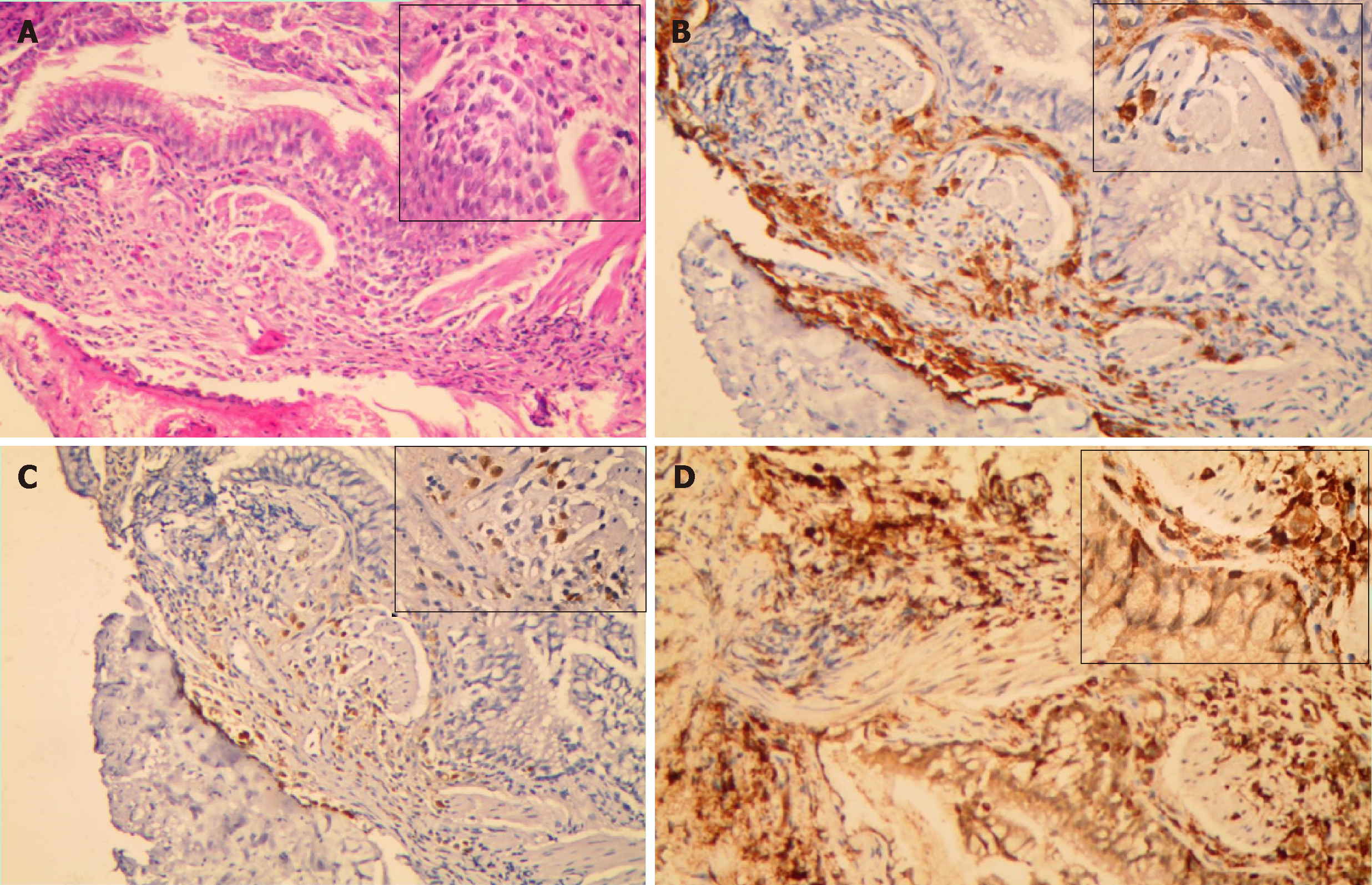

A fibreoptic bronchoscopy was performed to obtain transbronchial biopsies from the basal segment of right lower lobe. Haematoxylin-eosin staining showed a large number of typical Langerhans cells in the lung tissue, with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, irregular nuclei, and prominent folds and grooves. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positivity for CD1a, S100 and CD68 (Figure 2).

Based on the clinical manifestations and imaging and pathology findings, the final diagnosis was PLCH without extra-pulmonary involvement.

After comprehensively evaluating the patient's overall condition, we only recommended the patient to stop smoking, attend follow-up observation, and to not take other drugs during this time.

After smoking cessation, the symptoms of cough and phlegm improved markedly, there was no obvious dyspnoea, and the appetite had improved. Chest CT at 3 mo from the initial CT showed clear absorption of the nodules and thin-walled small holes (Figure 1C and Figure 1D). The patient is still being followed as of the writing of this report).

PLCH can occur at any age, but the majority of cases reported involve adults (aged between 20 years and 40 years) and particularly cigarette smokers[6,7]. The disorder is now considered as a form of smoking-related overreactive immune response in the lung tissue, complicated by chronic inflammation and ultimately resulting in Langerhans cells’ depositing into the interstitial area of the small airway[8-10].

Adult PLCH is generally diagnosed according to the presence of three main clinical manifestations[11-13]. The respiratory symptoms, usually cough and dyspnoea, occur in about two-thirds of cases; the constitutional symptoms of fever, malaise, sweats, and weight loss have been described in 15%–20% of cases. A second manifestation is the acute development of a spontaneous pneumothorax, seen in about 15%–20% of cases; the spontaneous pneumothorax can occur at any time during the course of disease. The third manifestation is an incidental finding on routine chest radiography, reported in 5%–25% of cases. Symptoms generally arise 6–12 mo prior to recognition of the disorder, but in some individuals the diagnosis is established after many years of observation. At late stages of the condition, PLCH patients may develop pulmonary hypertension, characterized by dyspnoea at rest and the features of right-ventricular circulatory failure. However, chest physical examination often does not detect significant pathological signs. The most common auscultations are weakened breathing sounds, wheezes, rales, and drum sounds in the pneumothorax. The first symptoms of our patient were cough and dyspnoea, and physical examination findings were non-specific, with only weakened breathing sounds and wheezing during lung auscultation.

PLCH has a very typical radiological pattern, which may be diagnostic if clinically consistent. Chest high-resolution (HR) CT demonstrates a combination of nodules, cavitating nodules measuring 1–10 mm in diameter, and thick-walled or thin-walled cysts[14,15]. Nodules and vacuolar nodules are common in the early disease state, while the appearance of advanced diseases is often cystic, or even honeycomb lung[14]. Imaging pulmonary lesions are mainly located in the upper and middle lung fields, with fewer pulmonary fundus. In our case, chest CT showed diffuse patchy ground glass opacity, irregular micronodules, and multiple thin-walled small holes in both lungs.

The characteristics of PLCH include the accumulation of a large number of CD1a+/CD207+ cells in loosely formed bronchiolocentric granulomas[16,17]. This results in airspace invasion, cavitation, and consequent destruction of lung parenchyma. However, the underlying molecular mechanism is still unclear. The CD1a+/CD207+ cells can be obtained by bronchoalveolar lavage, bronchoscopic lung biopsy, and video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery biopsy. Although transbronchial lung biopsies may show LCH granulomas, a definitive diagnosis of PLCH is most commonly obtained through video-assisted thoracoscopic surgical biopsy guided by HRCT findings[18]. Our patient was hospitalized for cough and dyspnoea and had abnormal chest CT examination. Immunohistochemical analysis of bronchoscopic lung biopsy detected CD1a+ cells and confirmed the diagnosis of PLCH.

At present, there is no definite therapeutic plan for PLCH. The first therapeutic approach recommended for patients affected by PLCH is smoking cessation[19,20]. Corticosteroids are the second method, applied after smoking cessation. Cytotoxic drugs (e.g., inblastine, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide) are also used to treat progressive PLCH. Cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine), a purine nucleoside analogue, has been reported to induce remission or improve lung disease in several PLCH cases[21,22]. Recently, a series of studies have confirmed that BRAF and MAP2K1 mutations occur in PLCH and that mutation-specific targeting therapy is effective[4]. For patients with recurrent pneumothorax, pleural fixation can be used to improve life treatment. Lung transplantation may be considered in patients with end-stage or severe pulmonary hypertension. Our patient had no underlying disease, isolated lung involvement, mild clinical symptoms and slight decline in lung function. Therefore, after comprehensive assessment of the condition, the treatment recommended was only smoking cessation and close follow-up. After 3 mo, the patient's symptoms had improved significantly, and chest CT showed that nodules were obviously absorbed. The effect of smoking cessation was, thus, good.

The natural history of the disease is variable and difficult to predict in a single patient. In some patients, HRCT abnormalities may disappear partially or completely without treatment, especially after smoking cessation. In the first 2 years after diagnosis, up to 40% of patients may have significant decreases in FEV1 or DLCO measurements[23]. Five years later, 50% of the patients will experience impaired lung function over time, and some patients will develop obstructive pulmonary disease[24]. In 10%-20% of patients, the first diagnosis is accompanied by severe clinical symptoms, which rapidly evolve into chronic cor pulmonale with progressive respiratory failure[11,25].

Follow-up with a physical examination, chest radiography and lung function tests should be performed periodically for PLCH. It is recommended that all patients undergo follow-up every 3–6 mo for the first year after diagnosis. Long-term follow-up is recommended and may detect respiratory dysfunction or a rare relapse with recurrent nodule formation[26]. After 3 mo of smoking cessation, our patient was re-examined and his condition had improved significantly. However, close follow-up was still needed to track any changes in the condition over time. Other interventions should be given as early as possible to improve the prognosis of the disease.

PLCH is a rare pulmonary cystic disease, and its pathogenic mechanisms are not yet fully understood. Diagnosis of PLCH depends on the pathological manifestations of CD1a+ cell aggregation. At present, there is no definite treatment plan for PLCH. The primary treatment is quit smoking; although, cladribine and BRAF inhibitors are the most promising methods for the treatment of aggressive PLCH. Individualized treatment strategies based on each patient's condition are needed and will improve outcomes. It is still necessary to carry out long-term follow-up and observation of PLCH cases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Turner AM S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: AE-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Emile JF, Abla O, Fraitag S, Horne A, Haroche J, Donadieu J, Requena-Caballero L, Jordan MB, Abdel-Wahab O, Allen CE, Charlotte F, Diamond EL, Egeler RM, Fischer A, Herrera JG, Henter JI, Janku F, Merad M, Picarsic J, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Rollins BJ, Tazi A, Vassallo R, Weiss LM; Histiocyte Society. Revised classification of histiocytoses and neoplasms of the macrophage-dendritic cell lineages. Blood. 2016;127:2672-2681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 722] [Cited by in RCA: 972] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aricò M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N, Emile JF, Lukina E, De Juli E, Danesino C. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the International Registry of the Histiocyte Society. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:2341-2348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weitzman S, Egeler RM. Langerhans cell histiocytosis: update for the pediatrician. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:23-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Torre O, Elia D, Caminati A, Harari S. New insights in lymphangioleiomyomatosis and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Vassallo R, Harari S, Tazi A. Current understanding and management of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Thorax. 2017;72:937-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Colby TV, Hartman T, Limper AH. Pulmonary Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1969-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tazi A. Adult pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir J. 2006;27:1272-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bratke K, Klug M, Bier A, Julius P, Kuepper M, Virchow JC, Lommatzsch M. Function-associated surface molecules on airway dendritic cells in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;38:655-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Merad M, Ginhoux F, Collin M. Origin, homeostasis and function of Langerhans cells and other langerin-expressing dendritic cells. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:935-947. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 580] [Cited by in RCA: 596] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Vassallo R, Walters PR, Lamont J, Kottom TJ, Yi ES, Limper AH. Cigarette smoke promotes dendritic cell accumulation in COPD; a Lung Tissue Research Consortium study. Respir Res. 2010;11:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vassallo R, Ryu JH, Schroeder DR, Decker PA, Limper AH. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans'-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wei P, Lu HW, Jiang S, Fan LC, Li HP, Xu JF. Pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis: case series and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mendez JL, Nadrous HF, Vassallo R, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Pneumothorax in pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Chest. 2004;125:1028-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Brauner MW, Grenier P, Mouelhi MM, Mompoint D, Lenoir S. Pulmonary histiocytosis X: evaluation with high-resolution CT. Radiology. 1989;172:255-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Brauner MW, Grenier P, Tijani K, Battesti JP, Valeyre D. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: evolution of lesions on CT scans. Radiology. 1997;204:497-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Roden AC, Yi ES. Pulmonary Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis: An Update From the Pathologists' Perspective. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:230-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kambouchner M, Basset F, Marchal J, Uhl JF, Hance AJ, Soler P. Three-dimensional characterization of pathologic lesions in pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:1483-1490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lorillon G, Tazi A. How I manage pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ninaber M, Dik H, Peters E. Complete pathological resolution of pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Respirol Case Rep. 2014;2:76-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wolters PJ, Elicker BM. Subacute onset of pulmonary langerhans cell histiocytosis with resolution after smoking cessation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190:e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lazor R, Etienne-Mastroianni B, Khouatra C, Tazi A, Cottin V, Cordier JF. Progressive diffuse pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis improved by cladribine chemotherapy. Thorax. 2009;64:274-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Grobost V, Khouatra C, Lazor R, Cordier JF, Cottin V. Effectiveness of cladribine therapy in patients with pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014;9:191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tazi A, de Margerie C, Naccache JM, Fry S, Dominique S, Jouneau S, Lorillon G, Bugnet E, Chiron R, Wallaert B, Valeyre D, Chevret S. The natural history of adult pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis: a prospective multicentre study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015;10:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tazi A, Marc K, Dominique S, de Bazelaire C, Crestani B, Chinet T, Israel-Biet D, Cadranel J, Frija J, Lorillon G, Valeyre D, Chevret S. Serial computed tomography and lung function testing in pulmonary Langerhans' cell histiocytosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:905-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Delobbe A, Durieu J, Duhamel A, Wallaert B. Determinants of survival in pulmonary Langerhans' cell granulomatosis (histiocytosis X). Groupe d'Etude en Pathologie Interstitielle de la Société de Pathologie Thoracique du Nord. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2002-2006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tazi A, Montcelly L, Bergeron A, Valeyre D, Battesti JP, Hance AJ. Relapsing nodular lesions in the course of adult pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:2007-2010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |