Published online Jul 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1884

Peer-review started: March 15, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Revised: May 3, 2019

Accepted: May 23, 2019

Article in press: May 23, 2019

Published online: July 26, 2019

Processing time: 136 Days and 18.3 Hours

Primary neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in the presacral region are extremely rare, some of which are caused by other primary tumors or metastatic rectal carcinoids. Nevertheless, cases of NETs have been increasing in recent years. This report describes the first primary neuroendocrine tumor in the presacral region that was found at our hospital within the last five years.

The patient was identified as a 36-year-old woman with a presacral mass and pelvic floor pain. A digital rectal examination revealed a presacral mass with unclear margins and obvious tenderness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 57 mm × 29 mm presacral lump. An ultrasound-guided needle biopsy confirmed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. No other primary or metastatic tumors were found.

Comprehensive consideration of our case report and literature reported by others suggests that a conclusive diagnosis of NETs should be based on computed tomography/MRI and pathological examinations. The treatment of primary NETs in the presacral region mainly relies on surgical procedures with follow-up.

Core tip: This case highlights the need to include neoplastic diseases in the differential diagnosis of any potentially benign perianal abscess. A 36-year-old Asian woman was initially diagnosed with perianal abscess. Ultrasound-guided needle biopsy confirmed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor, and then the patient underwent a sacrococcygeal tumor resection. A whole-body emission computed tomography scan was performed after the patient was discharged from the hospital, which revealed that she had no high expression of somatostatin receptors in the pleural cavity, abdominal cavity, or pelvis. There was no evidence of metastatic disease and no systemic symptoms or signs of carcinoid. These results confirmed that this was a primary presacral neuroendocrine tumor of level G2. The patient was advised to receive regular follow-up with her physician and magnetic resonance imaging.

- Citation: Zhang R, Zhu Y, Huang XB, Deng C, Li M, Shen GS, Huang SL, Huangfu SH, Liu YN, Zhou CG, Wang L, Zhang Q, Deng Y, Jiang B. Primary neuroendocrine tumor in the presacral region: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(14): 1884-1891

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i14/1884.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1884

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are tumors derived from neuroendocrine cells and peptidergic neurons. Research from the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results in the United States shows that the incidence of NETs has been increasing. A crude rate of occurrence has been estimated to be 5.85/100000 yearly, globally[1]. Although NETs occur mostly in the gastrointestinal tract (about 60%) and the broncho-pulmonary tract (about 30%), any part of the body may act as the primary site[2-4]. The clinical manifestations of NETs mainly depend on the type of hormones produced[5]. NETs are generally classified according to the Ki67 index and the mitotic index based on the 2010 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the digestive system. NETs are divided into three levels: (G1) mitotic index < 2/10 high-power fields and/or Ki67 index ≤ 2%; (G2) mitotic index 2-20/10 high-power fields and/or Ki67 index 3%-20%; and (G3) mitotic index > 20/ 10 high-power fields and/or Ki67 index > 20%. G1 and G2 identify NETs, and G3 identifies neuroendocrine carcinomas. Over 5 years, the survival rates of patients diagnosed with G1, G2, and G3 NET were 95.7%, 73.4%, and 27.7%, respectively. The prognosis for treatment is based on the degree of differentiation, with the higher degree leading to a better prognosis after treatment[6].

This study reports a case of primary well-differentiated NET in the presacral region. This case is an infrequent case of NET without any other primary tumor or metastatic tumor. In addition, we summarize our results regarding the diagnosis and review the literature on presacral NETs for collecting a comprehensive overview of these very rare tumors.

Anal discomfort for 1 mo.

A 36-year-old Asian woman had symptoms including a lump and pelvic pain. On March 11, 2018, she suffered from progressive pain. A pelvic computed tomography scan revealed an elliptical mass in the right side of the adnexa and in the left pelvis; this round mass, about 25 mm × 35 mm, appeared as circular-shaped soft tissue between the rectum and sacrum. A routine blood test revealed a white blood cell count of 11.34 × 109/L and neutrophil percentage at 84.3%. The patient then visited our outpatient department due to the intolerable pain in the sacrococcygeal region, and we diagnosed it as a suspected perianal abscess.

Two years before her enrollment, the patient suffered from pelvic pain due to an accidental falling and did not accept any imaging examination or therapy.

The patient was previously healthy and her family history was unremarkable.

There was no swelling between the anus and the sacrococcyx, but a mass which was full and had an unclear boundary and obvious tenderness could be touched. The internal anus was not obviously abnormal, and no blood was detected when we did digital rectal examination.

Analysis of peripheral blood showed a neutrophil percentage of 88.01% and 27.3 ng/mL of neuron-specific enolase.

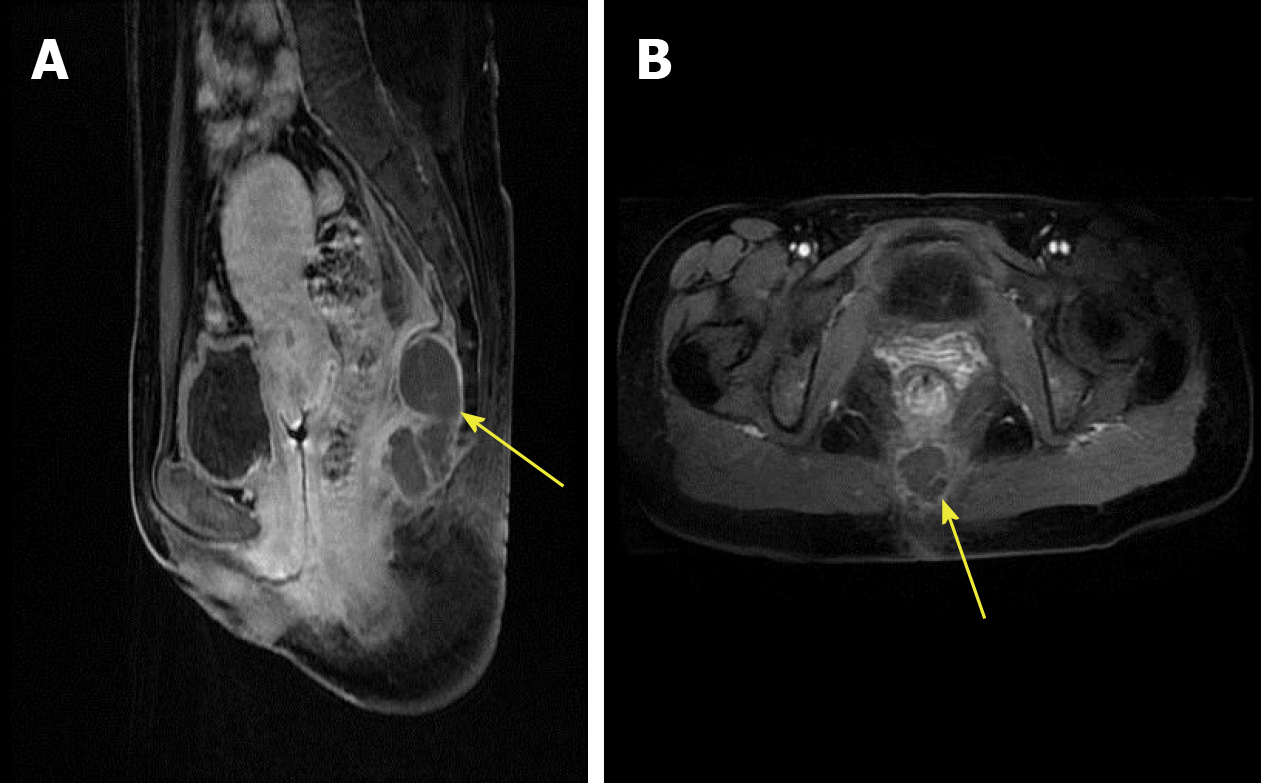

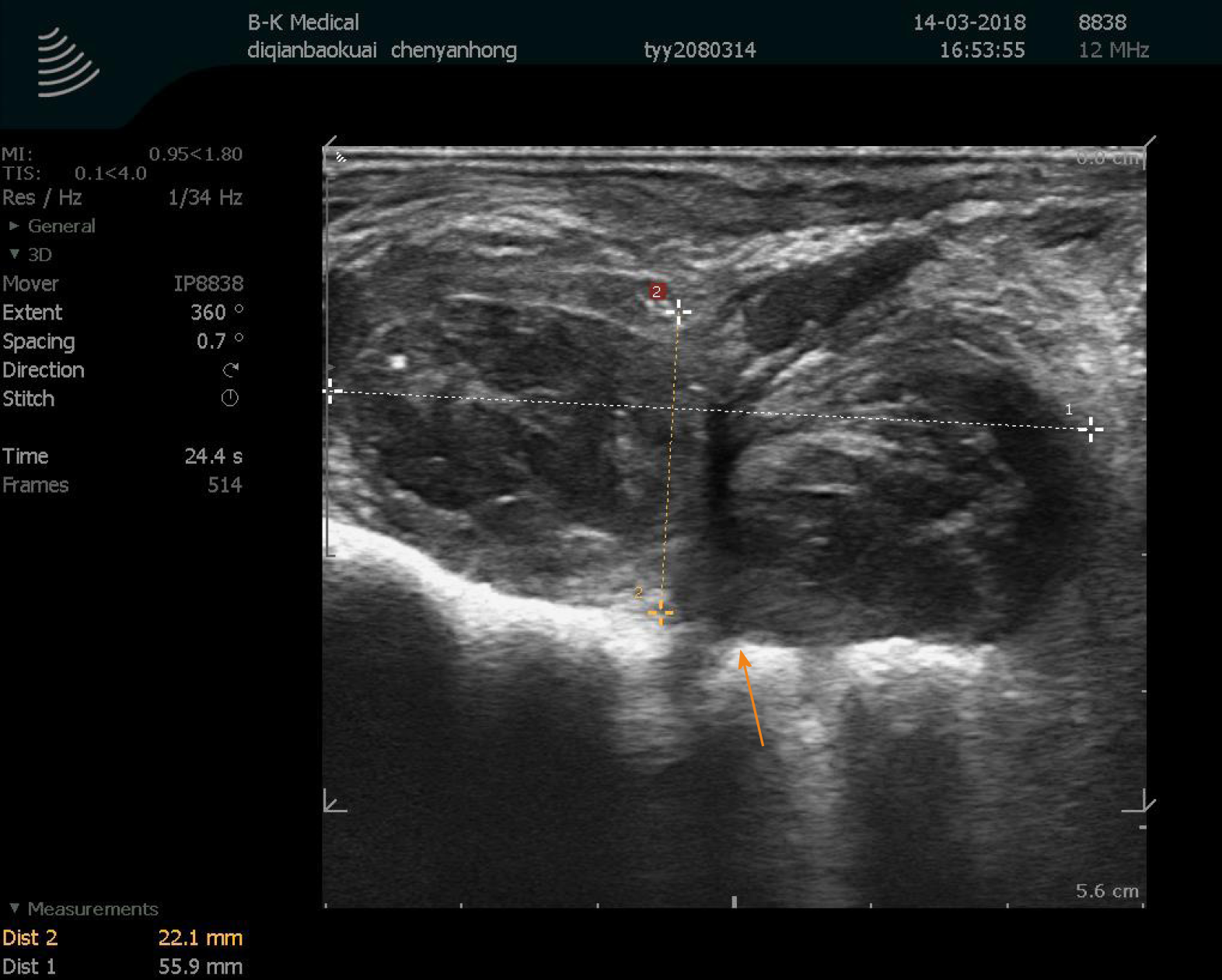

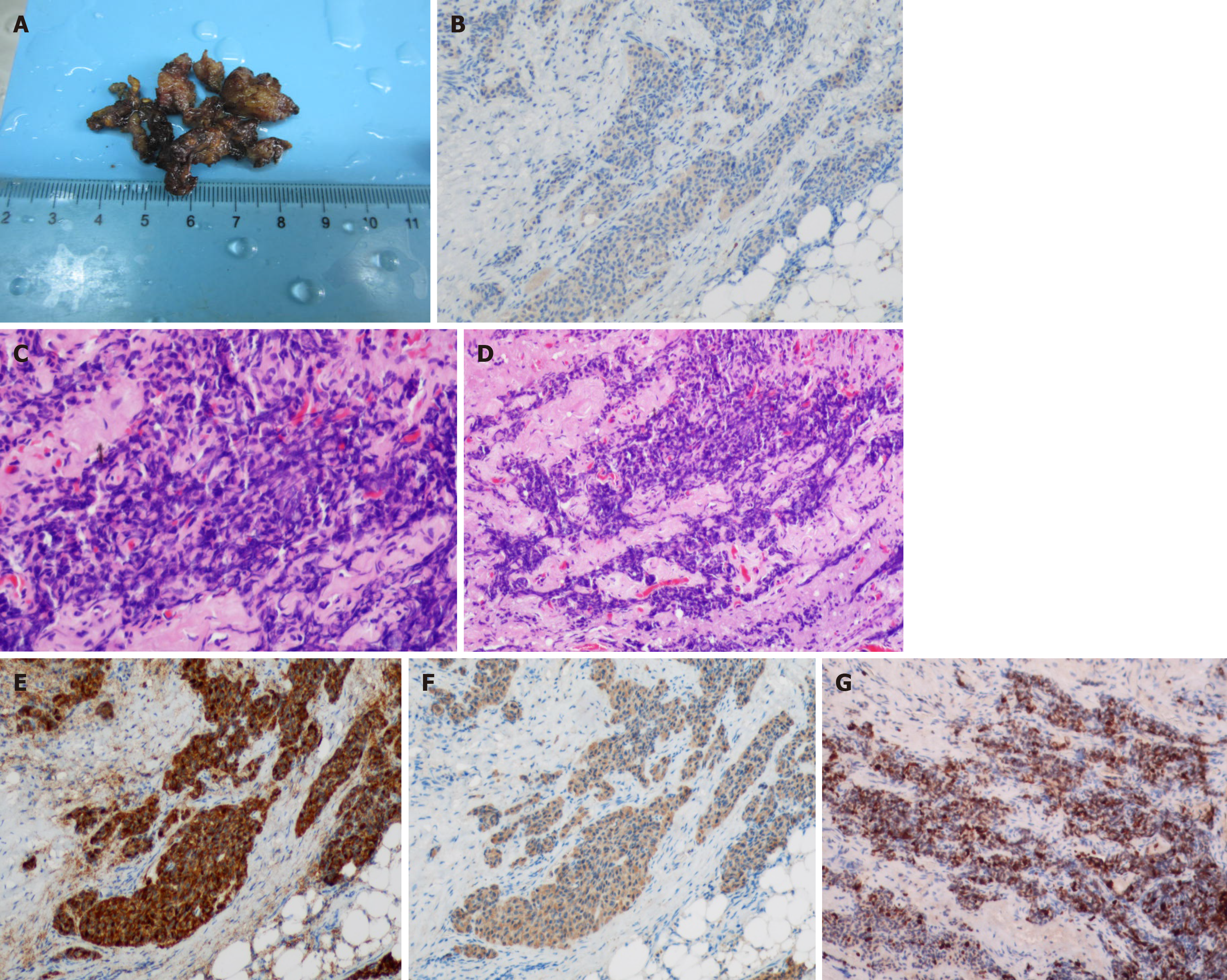

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) identified a 57 mm × 29 mm presacral mass, and margin and separation were visible (Figure 1). Transanal endoscopic ultrasound revealed a non-homogeneous echo-poor area 6 cm away from the sacral coccyx and in the direction of the sacrum, and a hyperechoic periosteum with a clear membrane but no abundant internal blood flow (Figure 2). On April 24, 2018, the patient underwent a sacrococcygeal tumor resection. The tumor was located in the anterior rectum 5 cm from the anus (Figure 3A). No tumor tissue remained after the resection.

The final pathology report showed that the tumor was a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor with a Ki67 index of 30% (Figure 3G). No nerve or lymphatic invasion was observed. Immunohistochemistry tested positive for neural cell adhesion molecule (CD56) (Figure 3E), CK2 (Figure 3F), and Syn (Figure 3B).

There was no evidence of metastatic disease and no systemic symptoms or signs of carcinoid syndrome (Figure 4). These results confirmed that this was a primary presacral neuroendocrine tumor of level G2. The patient was advised to receive regular follow-up with her physician and MRI.

On March 11, 2018, a small amount of pus was withdrawn during surgery, and the transanal endoscopic ultrasound showed that this was a solid mass. According to the patient's symptoms and signs, an abscess incision was performed with antibiotic therapy and an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy confirmed a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. On April 24, 2018, the patient underwent a sacrococcygeal tumor resection.

One month later, a whole-body emission computed tomography (ECT) scan was performed after the patient was discharged from the hospital. The whole-body ECT scan did not show high expression of somatostatin receptors in the pleural cavity, abdominal cavity, or pelvis.

The number of reported NET cases has increased in past decades because of improvements in diagnostic modalities and surveillance[7,8], but primary NETs in the presacral region are extremely rare. The sacrococcygeal tumors usually remain clinically silent for a long period of time. A physical mass and pelvic pain are often discovered in the context of nerve root compression. For adults, primary tumors arising in this area include chordomas, myxopapillary ependymomas, para-gangliomas, schwannomas, liposarcomas, and chondrosarcomas, etc.[9,10] Some NETs can also result from the metastasis of rectal carcinoids[11].

As shown in this case, a colonoscopy was not performed and a gastrointestinal tract NET was not considered since NETs in the presacral region are very rare, the patient’s previous symptoms aligned with those of an abscess, and the doctor had little experience in this kind of tumor. Along the lines, masses in the presacral region are difficult to pre-diagnose and are reported as NETs by biopsy much later. The current methods for diagnosing NETs include: (1) Somatostatin-receptor nuclear imaging; (2) CT/MRI; and (3) biopsy. NETs are then classified according to the Ki67 index and the mitotic index. At the same time, NET phenotypes can be divided into functional and non-functional tumors based on the absence or presence of hormones and the presence of hormone-related symptoms[5]. While hormone-related markers were not detected in the current case, it was unclear whether the patient suffered from hormone-related symptoms. Consequently, it was also difficult to distinguish whether the tumor was functional or non-function in this case.

Studies have shown that somatostatin-receptor nuclear imaging should be performed as a baseline preoperative test to detect whether a strong SSRT2A immune response is observed in tumor tissues[12]. In this case, the whole-body ECT did not show high expression of somatostatin receptors in the pleural cavity, abdominal cavity, or pelvis.

For treatment, surgery with follow-up is the main form of treatment for NETs in the presacral region. In addition, somatostatin analogs are appropriate initial therapies for most patients with unresectable metastatic NETs for the control of carcinoid syndrome and inhibition of tumor growth. SSAs are typically selected as the first-line systemic therapy[13-15]. In this case, the symptoms of recovery were pain relief and reduced mass size after pus withdrawal. With the mass remaining in the presacral region and a biopsy likely necessary to determine the pathological tendency, there was a risk for exacerbation and the patient needed a sacrococcygeal tumor resection. Nevertheless, the entire body ECT did not show high expression of somatostatin receptors in the pleural cavity, abdominal cavity, or pelvis. Therefore, there was no evidence of metastatic disease and no systemic symptoms or signs of carcinoid syndrome in the end.

Among the 11 cases of primary tumor in the presacral region that we found to be previously reported, the tumors were located mostly within the sacrum[16-26], with one case located at the anorectal junction[18]. Seven of the eleven patients were male. This prompted us to consider the possibility of a relationship between hormones and tumor location (Table 1)[16-26]. Of note, five were associated with a retrorectal cystic hamartoma which was also known as “Tailgut cyst”[16,18,19,24,25]. From those, three originated from a carcinoid tumor, one from a sacrococcoidal carcinoid[22], one from an anterior tibial neuroendocrine tumor[17], and one from a poorly differentiated large cell carcinoma[26].

| Ref. | Year | Sex/age | Size (cm) | Associatedanomalies | Symptoms | Biopsy | Treatment | Follow-up |

| Jehangir et al[18] | 2016 | M/71 | NA | Tailgut cyst | No | CD56+ AE1/AE3+ CgA+ | Surgery | 5 Y |

| Lokesh Bathlaet al[19] | 2013 | F/46 | 6 × 6 × 6 | Tailgut cyst | Constipation | Syn+ NSE+ | Surgery | 6 M |

| Fannyet al[17] | 2009 | M/72 | NA | Neuroendocrine tumor | Pain | Neurosecretory granules+ | Radiation- therapy | 28 Y |

| Stefano et al[16] | 2010 | F/73 | 3.9 × 3.2 | Tailgut cyst | Pain | Chromogranin+ Syn+ | Surgery | 10 M |

| Luonget al[22] | 2005 | M/37 | 7 | Sacrococcoidal carcinoid | Pain | NA | SSAs | NA |

| Mathieu et al[23] | 2005 | F/49 | NA | Carcinoid tumor | Mass | NA | NA | NA |

| Krasinet al[21] | 2001 | F/40 | 5 × 5 | Carcinoid tumor | Mass pain | Chromogranin+ Keratin++ | Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 4 Y |

| Theunissen et al[26] | 2001 | F/51 | 7 × 5 × 5 | Poorly differentiated large cell carcinoma | Pain | NA | Chemotherapy | NA |

| Prasad et al[25] | 2000 | F/36-69 | 20– 12 | Hamartoma | Pain Bleeding | Syn+ SSRT2A+ | Surgery | NA |

| Oyama et al[24] | 2000 | M/52 | 22 | Tailgut cyst | Mass | Syn+ | NA | NA |

| Fiandaca et al[20] | 1988 | F/35 | NA | Carcinoid tumor | NA | NA | NA | NA |

The main symptoms of the tumor were pain and the presence of a mass, which are also reported in Table 1. Biopsies generally showed positive tumor markers, but not every case had detected SSRT2A. Surgery was the main treatment. If metastasis was observed, adjuvant therapy was needed mainly for SSAs.

The average follow-up time of reported cases was 41.8 mo[16-26]. Most of the patients were alive at the time of the clinical follow-up control. Patients with well-differentiated presacral NETs that only showed a local disease often showed a good prognosis. There was even a patient who had been followed for 28 years after radiotherapy[17]. However, patients with distant metastases need more investigation.

In summary, primary NETs in the presacral region are very rare, and the clinical presentation often involves pain and the presence of a mass. The imaging performance of these tumors is indistinguishable from that of the other tissue masses in this area, making diagnosis difficult. Currently, the most common diagnostic method for NETs is still based on biopsy. If biopsy confirms a well-differentiated NET, a colonoscopy is needed to exclude metastatic disease. In terms of treatment, surgical excision is needed to remove the primary tumor, and follow-ups are necessary to prevent recurrent attacks and metastases.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu G, Ortiz-Sanchez E S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Hallet J, Law CH, Cukier M, Saskin R, Liu N, Singh S. Exploring the rising incidence of neuroendocrine tumors: a population-based analysis of epidemiology, metastatic presentation, and outcomes. Cancer. 2015;121:589-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 612] [Article Influence: 55.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Cives M, Strosberg JR. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:471-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 404] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Hilal T. Current understanding and approach to well differentiated lung neuroendocrine tumors: an update on classification and management. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9:189-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huguet I, Grossman AB, O'Toole D. Changes in the Epidemiology of Neuroendocrine Tumours. Neuroendocrinology. 2017;104:105-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Modlin IM, Moss SF, Gustafsson BI, Lawrence B, Schimmack S, Kidd M. The archaic distinction between functioning and nonfunctioning neuroendocrine neoplasms is no longer clinically relevant. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:1145-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Abdel-Rahman O, Fouad M. Bevacizumab-based combination therapy for advanced gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (GEP-NENs): a systematic review of the literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2015;141:295-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rindi G, Klimstra DS, Abedi-Ardekani B, Asa SL, Bosman FT, Brambilla E, Busam KJ, de Krijger RR, Dietel M, El-Naggar AK, Fernandez-Cuesta L, Klöppel G, McCluggage WG, Moch H, Ohgaki H, Rakha EA, Reed NS, Rous BA, Sasano H, Scarpa A, Scoazec JY, Travis WD, Tallini G, Trouillas J, van Krieken JH, Cree IA. A common classification framework for neuroendocrine neoplasms: an International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and World Health Organization (WHO) expert consensus proposal. Mod Pathol. 2018;31:1770-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 546] [Cited by in RCA: 713] [Article Influence: 101.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Deutsch GB, Lee JH, Bilchik AJ. Long-Term Survival with Long-Acting Somatostatin Analogues Plus Aggressive Cytoreductive Surgery in Patients with Metastatic Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;221:26-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Thornton E, Krajewski KM, O'Regan KN, Giardino AA, Jagannathan JP, Ramaiya N. Imaging features of primary and secondary malignant tumours of the sacrum. Br J Radiol. 2012;85:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gerber S, Ollivier L, Leclère J, Vanel D, Missenard G, Brisse H, de Pinieux G, Neuenschwander S. Imaging of sacral tumours. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:277-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ghosh J, Eglinton T, Frizelle FA, Watson AJ. Presacral tumours in adults. Surgeon. 2007;5:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Satpati D, Shinto A, Kamaleshwaran KK, Sarma HD, Dash A. Preliminary PET/CT Imaging with Somatostatin Analogs [68Ga]DOTAGA-TATE and [68Ga]DOTAGA-TOC. Mol Imaging Biol. 2017;19:878-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vinik AI, Wolin EM, Liyanage N, Gomez-Panzani E, Fisher GA, ELECT Study Group *. Evaluation of lanreotide depot/autogel efficacy and safety as a carcinoid syndrome treatment (ELECT): a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Endocr Pract. 2016;22:1068-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kunz PL. Carcinoid and neuroendocrine tumors: building on success. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1855-1863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | O'Toole D, Ducreux M, Bommelaer G, Wemeau JL, Bouché O, Catus F, Blumberg J, Ruszniewski P. Treatment of carcinoid syndrome: a prospective crossover evaluation of lanreotide versus octreotide in terms of efficacy, patient acceptability, and tolerance. Cancer. 2000;88:770-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | La Rosa S, Boni L, Finzi G, Vigetti D, Papanikolaou N, Tenconi SM, Dionigi G, Clerici M, Garancini S, Capella C. Ghrelin-producing well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor (carcinoid) of tailgut cyst. Morphological, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and RT-PCR study of a case and review of the literature. Endocr Pathol. 2010;21:190-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Dujardin F, Beaussart P, de Muret A, Rosset P, Waynberger E, Mulleman D, de Pinieux G. Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the sacrum: case report and review of the literature. Skeletal Radiol. 2009;38:819-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jehangir A, Le BH, Carter FM. A rare case of carcinoid tumor in a tailgut cyst. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2016;6:31410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bathla L, Singh L, Agarwal PN. Retrorectal cystic hamartoma (tailgut cyst): report of a case and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:204-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fiandaca MS, Ross WK, Pearl GS, Bakay RA. Carcinoid tumor in a presacral teratoma associated with an anterior sacral meningocele: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:581-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Krasin E, Nirkin A, Issakov J, Rabau M, Meller I. Carcinoid tumor of the coccyx: case report and review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:2165-2167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Luong TV, Salvagni S, Bordi C. Presacral carcinoid tumour. Review of the literature and report of a clinically malignant case. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:278-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mathieu A, Chamlou R, Le Moine F, Maris C, Van de Stadt J, Salmon I. Tailgut cyst associated with a carcinoid tumor: case report and review of the literature. Histol Histopathol. 2005;20:1065-1069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Oyama K, Embi C, Rader AE. Aspiration cytology and core biopsy of a carcinoid tumor arising in a retrorectal cyst: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2000;22:376-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Prasad AR, Amin MB, Randolph TL, Lee CS, Ma CK. Retrorectal cystic hamartoma: report of 5 cases with malignancy arising in 2. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:725-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Theunissen P, Fickers M, Goei R. Primary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the presacral region. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:880-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |