Published online Jul 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1857

Peer-review started: April 1, 2019

First decision: April 30, 2019

Revised: May 13, 2019

Accepted: May 23, 2019

Article in press: May 23, 2019

Published online: July 26, 2019

Processing time: 117 Days and 2.2 Hours

Because the duodenum is fixed onto the retroperitoneum, duodenal intussusception is usually impossible except in cases of malrotational abnormality. Although cases of duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormalities have been reported, it is unclear whether they constitute true intussusception or simple mucosal prolapse.

A 66-year-old woman presented with whole-body edema and malaise. Blood analysis indicated severe anemia and cholestasis. Endoscopic examination revealed a pedunculate polyp on the second part of the duodenum that migrated distally with mucosal elongation. Computed tomography showed duodenal intussusception. A tumor as the lead point and retroperitoneal structure, including the head of the pancreas and fat, invaginated beyond the duodenojejunal flexure. She was diagnosed with ampullary adenoma caused repeated intussusception that reduced spontaneously and underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Laparotomy showed tumor prolapse beyond the duodenojejunal flexure without intussusception. There was no evidence of malrotational abnormality. She was discharged with no complications.

We report true duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormality. This phenomenon was also associated with mucosal prolapse.

Core tip: Duodenal intussusception is usually impossible except in cases of malrotational abnormality. Some cases of duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormalities have been reported, but it is unclear whether this phenomenon is true intussusception or simple mucosal prolapse. We present a case of true duodenal intussusception secondary to ampullary adenoma without malrotational abnormality. Computed tomography showed a tumor as the lead point and retroperitoneal structure, including the head of the pancreas and fat, invaginating beyond the duodenojejunal flexure to the jejunum. This phenomenon was associated with mucosal prolapse.

- Citation: Hirata M, Shirakata Y, Yamanaka K. Duodenal intussusception secondary to ampullary adenoma: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(14): 1857-1864

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i14/1857.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i14.1857

Intussusception can occur anywhere in the small and large intestines. However, duodenal intussusception is rarely encountered because the duodenum is fixed onto the retroperitoneum. Therefore, duodenal intussusception is usually impossible, except in cases of malrotational abnormality[1,2], which permits excessive mobility of the duodenal wall. Some cases of duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormalities have been reported, but it is unclear whether this phenomenon is true intussusception or simple mucosal prolapse[1-5]. Here, we present a case of true duo-denal intussusception secondary to ampullary adenoma without malrotational abnormality.

A 66-year-old woman presented to our hospital complaining of whole-body edema and general malaise.

The patient’s symptoms started 6 mo prior, with recurrent episodes of epigastric discomfort after meals. These symptoms gradually improved spontaneously.

The patient had a medical history free of illness.

The patient had no family history of familial adenomatous polyposis.

Physical examination revealed pallor but no tenderness or palpable tumor in the abdomen.

Blood analysis showed severe microcytic anemia (hemoglobin level 3.6 g/dL) and cholestasis. The type of anemia was iron deficiency, as revealed by a serum iron level of 5.0 μg/dL (normal range: 45-170 μg/dL) and a serum ferritin level of 0 ng/mL (normal: 5-152 ng/mL). In addition, the patient had a serum gamma-glutamyltran-speptidase level of 187 IU/L (normal: 5-30 IU/L) and a serum alkaline phosphatase level of 851 IU/L (normal: 100-300 IU/L), though her serum total bilirubin level was normal. Amylase was also not elevated. Although these factors did not lead to jaundice, the cholestasis gradually worsened until surgery (serum gamma-glutamyl-transpeptidase level 614 IU/L, serum alkaline phosphatase level 3515 IU/L).

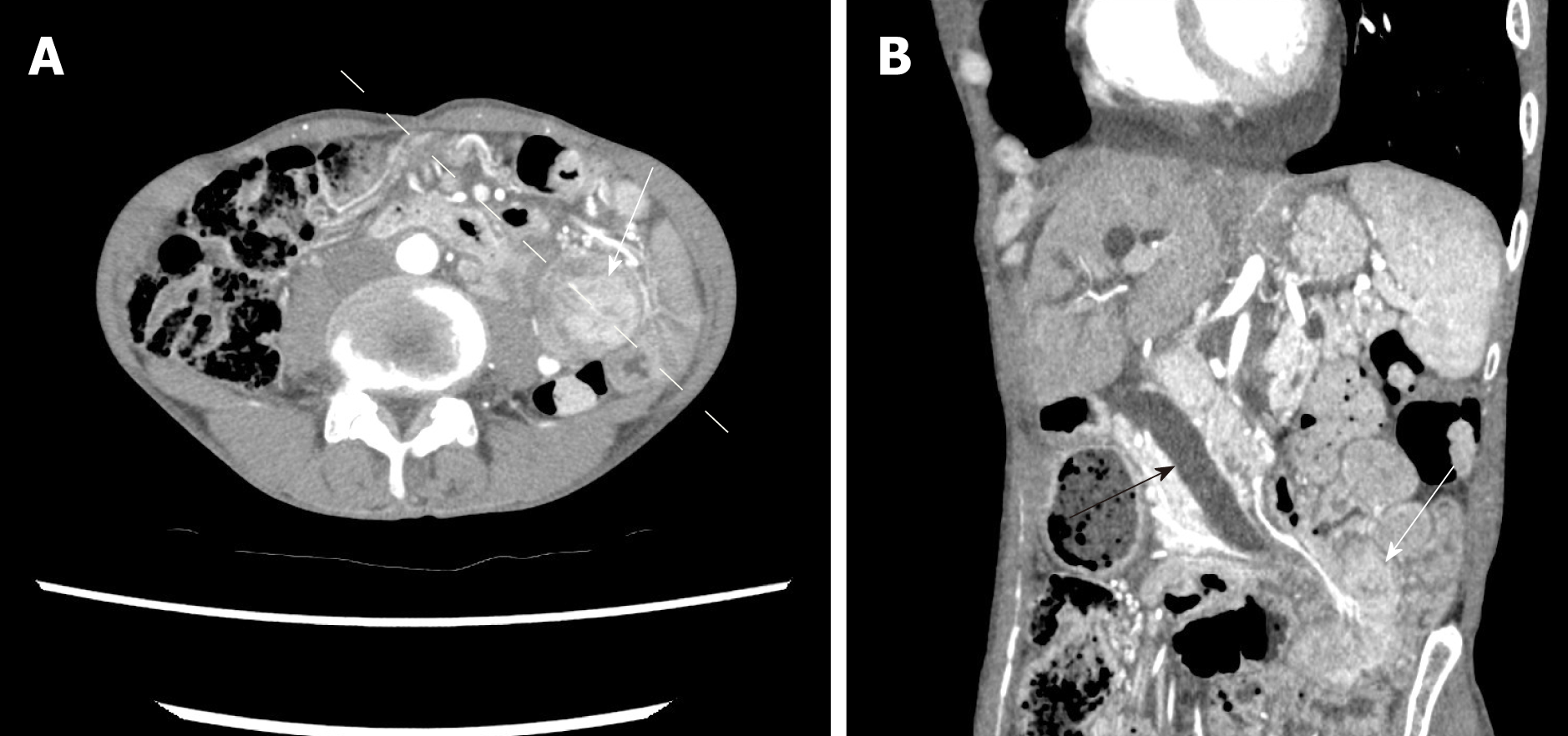

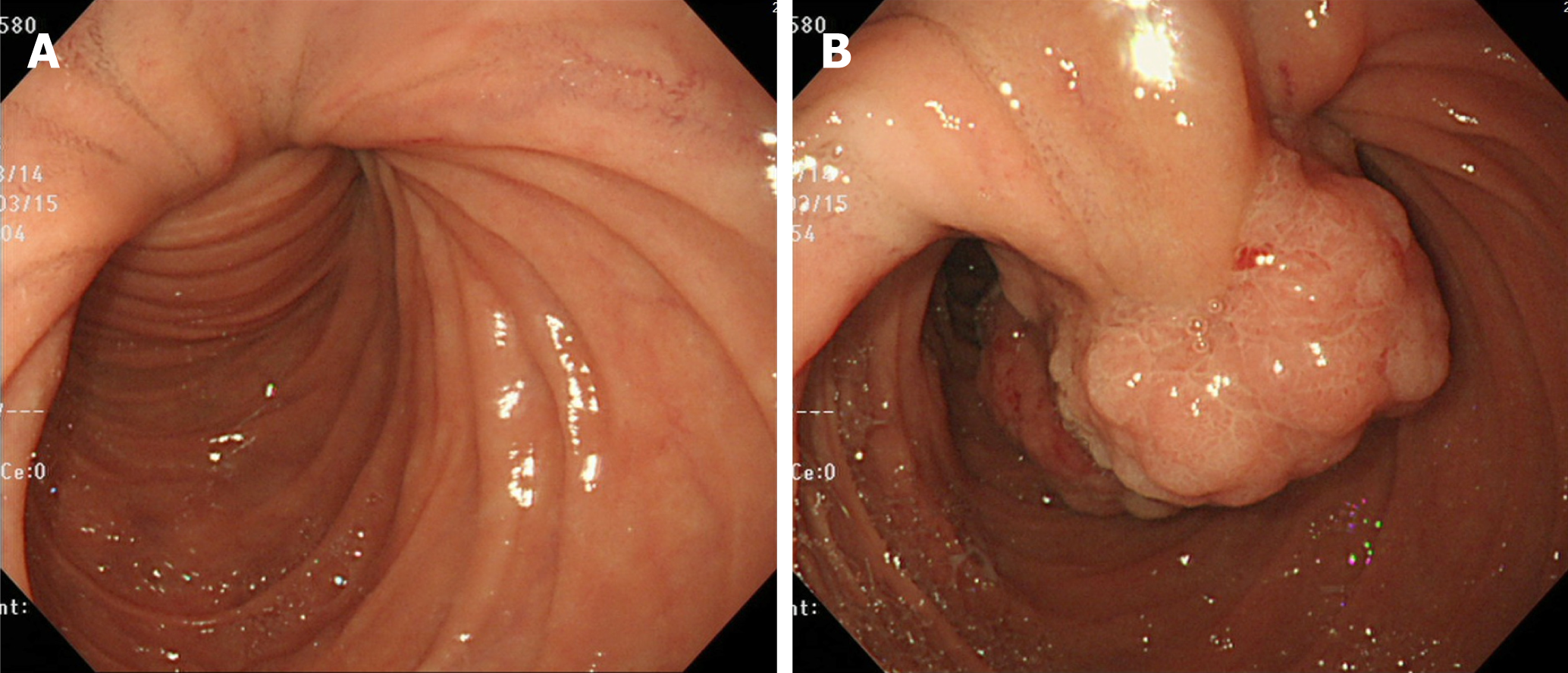

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) on admission demonstrated a 4.5 cm tumor at the proximal jejunum. The whole structures surrounding the ampulla, including the common bile duct (CBD) and the major pancreatic duct, deviated in the left-lower direction. Intussusception was not identified (Figure 1). Furthermore, drip infusion cholecystocholangiography-CT showed dilatation of the CBD-intrahepatic bile duct and marked left-lower deviation of the CBD and ampulla (Figure 2). The tumor was further evaluated by endoscopy, revealing a pedunculate papillary polyp with minor bleeding located on the second part of the duodenum that migrated distally with mucosal elongation (Figure 3). Biopsy material from the tumor indicated an adenoma without malignancy. Because the ampulla was not identified by endoscopy, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was not performed.

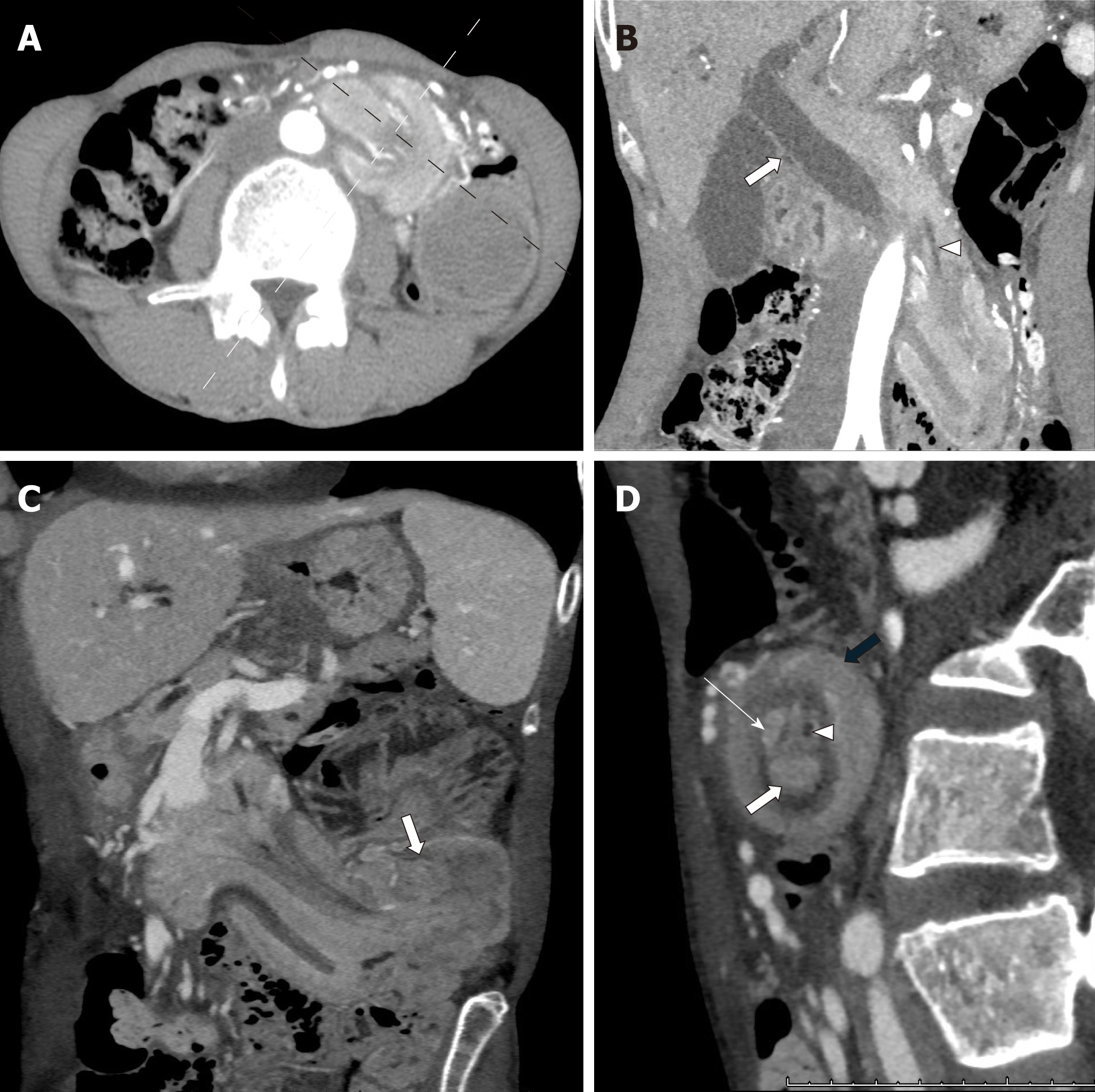

Because of the progression of cholestasis, we conducted follow-up CT of the abdo-men 3 d after admission, and the scan revealed duodenal intussusception (Figure 4). A tumor as the lead point and retroperitoneal structure, including the head of the pancreas and fat, was observed to invaginate beyond the duodenojejunal flexure to the jejunum. The target sign appeared when the CT beam was perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the intussusception. The whole structures surrounding the ampulla were further deviated toward the left-lower direction. Ischemia of the bowel was not observed.

The final diagnosis of the presented case is ampullary adenoma repeating intussu-sception and its reduction.

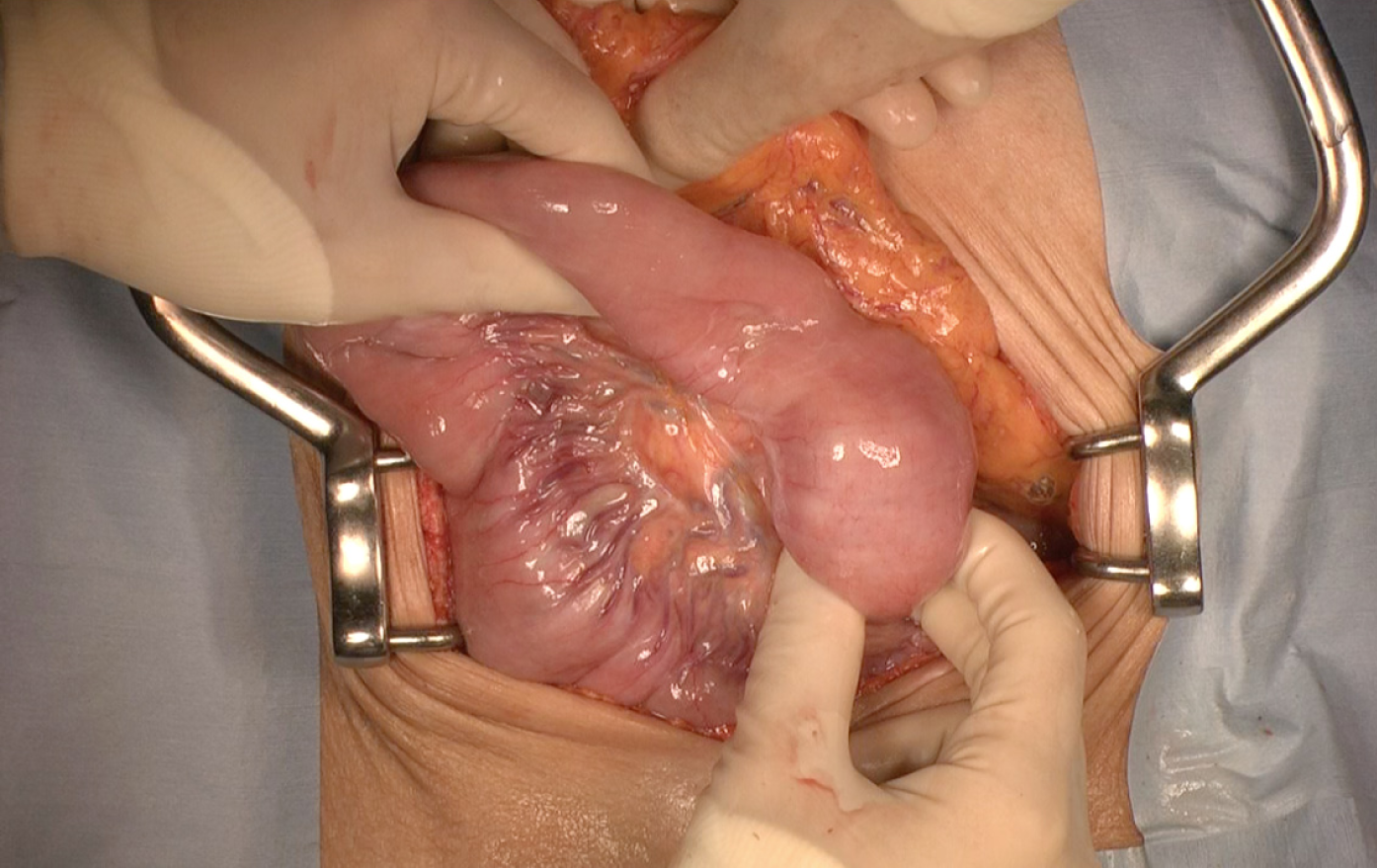

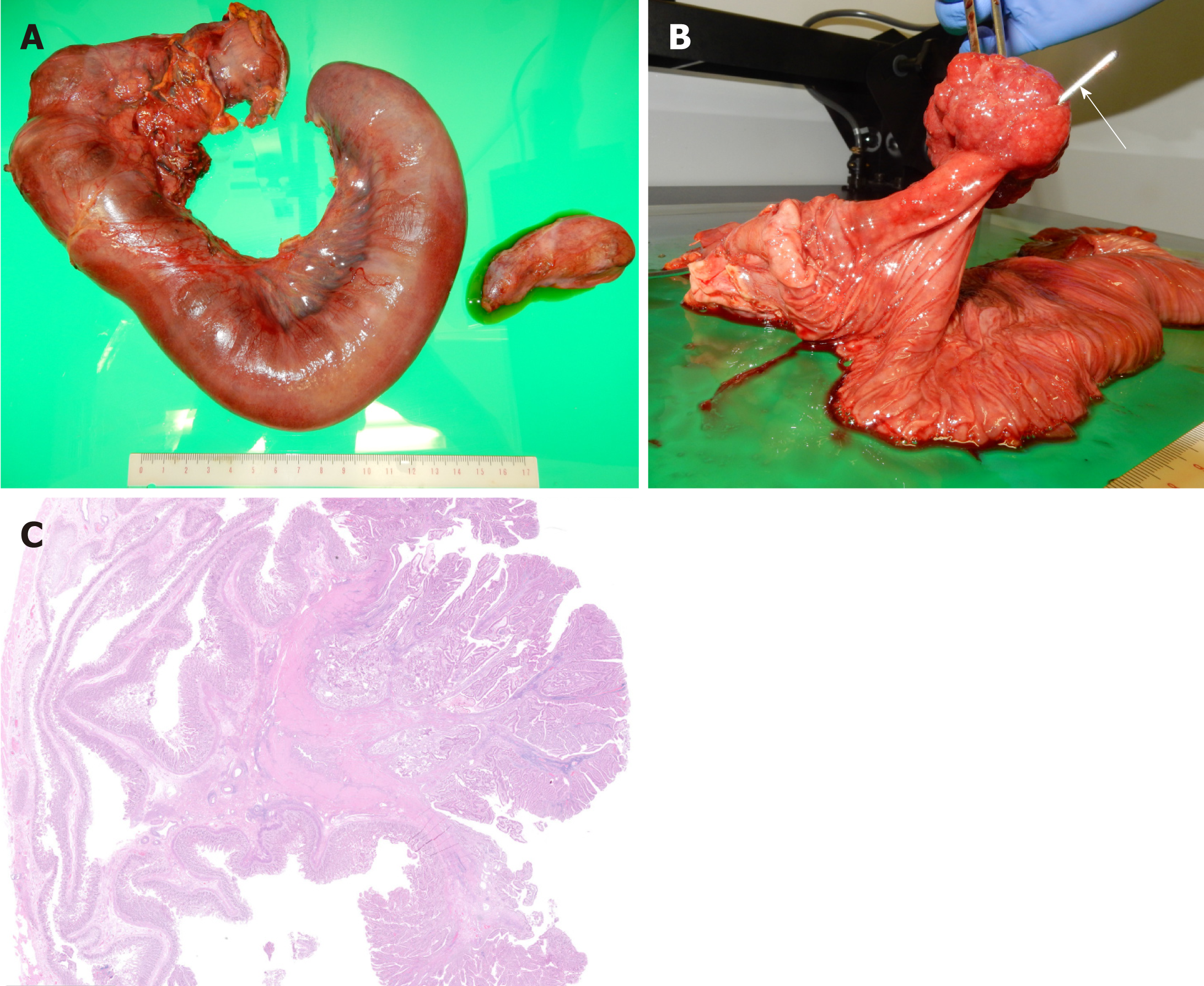

The patient underwent subtotal stomach-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy at one month after admission. Laparotomy showed that the intraduodenal tumor had prolapsed beyond the duodenojejunal flexure to the proximal jejunum, but intussusception was not identified (Figure 5). The tumor easily slid back into the second part of the duodenum, and we found no evidence of malrotation or incomp-lete fixation of the duodenum. The patient was discharged 4 weeks after the operation with no trouble.

Histology confirmed a 4.5 cm × 3.8 cm × 2.6 cm ampullary tubulovillous adenoma with no dysplasia originating from the duodenal epithelium in the papilla of Vater (Figure 6). There was no evidence of intraductal extension or malignancy. The patient has had no symptoms for a year postoperatively.

Intussusception is defined as the invagination of one segment of the bowel into an immediately adjacent segment[6]. As this complication requires free mobility of the intestine, duodenal intussusception is usually impossible because a large portion of the duodenum is fixed to the retroperitoneum, except in cases of malrotational abnormality[1,2]. However, there are some reports of cases of duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormalities. Saida et al[4] noted that distal migration of duodenal tumors might have been misinterpreted as intussusception in most of these reports. Distal migration can occur as a result of mucosal elongation and slipping. This phenomenon was introduced as mucosal prolapse[2,3], whereby the enveloping mucosa is elongated and results in a mucosal stalk as a tumor migrates distally by peristalsis. If the tumor migrates more distally, the wall of the duodenum and proximal jejunum become deformed. A schema by Greenwald et al[7] also suggested mucosal prolapse, though this complication was termed intussusception.

The diagnosis of intussusception has been based on a classic radiologic “coiled-spring sign” on contrast radiographs or a “target sign” on CT or ultrasonography; however, mucosal prolapse can mimic these signs without evidence of intussu-sception[8,9]. Indeed, for a definitive diagnosis of intussusception, the coiled-spring sign should have a structure consisting of multiple layers to reflect involvement of the intussuscipiens and intussusceptum; the target sign should also have fatty elements, including mesentery and omentum[10]. True intussusception involves invagination of the entire thickness of the bowel wall and its mesentery into the adjacent bowel. Moreover, clear visualization of a fat plane between the bowel walls is necessary when CT is used for diagnosis[11]. There have been no reports to date showing these findings in detail in a case of duodenal intussusception.

In our case, invaginating fatty elements, including the head of the pancreas, were identified in the target sign on follow-up CT. Therefore, we concluded that duodenal intussusception was present. In duodenal intussusception, invaginating mesentery will coincide with the head of the pancreas. To the best of our knowledge, the presented case is the first in the literature to clearly describe duodenal intussusception without malrotational abnormality. Furthermore, we confirmed mucosal prolapse in this case. Endoscopic and intraoperative findings suggested mucosal prolapse. Although CT on admission did not show intussusception, the ampullary tumor was identified at the proximal jejunum, and the whole structures surrounding the ampulla were similarly deviated toward the left-lower direction, also suggesting mucosal prolapse.

The enveloping mucosa is always elongated distally as mucosal prolapse, and the wall of the duodenum and proximal jejunum become deformed due to peristalsis. A more strongly elongated mucosa appears to lead to intussusception, and the head of the pancreas is pulled along with the mucosa. However, intussusception does not last for a long time and reduces spontaneously, as in this case. Therefore, bowel ischemia was not present in this case. Although the pathogenesis of this condition remains unclear, retrograde traction may occur as the invagination progresses more distally because of the lack of mobility of the duodenum and pancreas. Duodenal intussu-sception appears to be an extension of mucosal prolapse.

In our case, intermittent compression of the CBD and pancreatic duct caused by the intussuscepted duodenal segment led to massive duct dilation and cholestasis. This dilation was not caused by obstruction due to the tumor itself because the tumor pathologically invaded neither the bile duct nor the pancreatic duct. Moreover, the patient’s serum total bilirubin level did not rise because even though it was compressed, the bile duct was not completely obstructed; nonetheless, the cholestasis gradually worsened until surgery. If not treated properly, jaundice and pancreatitis might ensue. Severe anemia was also present due to minor chronic bleeding of the tumor and not by the intussusception. In cases of duodenal intussusception, it is important to carefully consider pancreaticobiliary symptoms in addition to bowel obstruction.

Less-invasive surgical ampullectomy, as opposed to pancreaticoduodenectomy, can be considered as a treatment for ampullary adenoma[12,13]. However, we performed pancreaticoduodenectomy because there is a risk of injury to the pancreatic parenchyma with surgical ampullectomy[14,15]. We suspected that the parenchyma of the head of the pancreas had been chronically stretched beyond the duodenal muscularis propria with the common channel by the intussusception and mucosal prolapse, though this could not be proven pathologically. Considering the risk of tumor malignancy and that surgical ampullectomy is not a frequently performed procedure, pancreaticoduodenectomy is an appropriate choice in such cases.

Duodenal intussusception is possible even if there is no malrotational abnormality. This phenomenon is also associated with mucosal prolapse. Pancreaticobiliary symptoms in addition to bowel obstruction should be considered in duodenal intussusception. This case report may contribute to clarifying the pathology of duo-denal intussusception.

We are thankful to Dr. Genki Fukumoto for helpful discussions.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ciocalteu A, Shin SJ S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wang J

| 1. | Chalmers N, De Beaux AC, Garden OJ. Case report: prolapse of an ampullary tumour beyond the duodeno-jejunal flexure. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:141-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gardner-Thorpe J, Hardwick RH, Carroll NR, Gibbs P, Jamieson NV, Praseedom RK. Adult duodenal intussusception associated with congenital malrotation. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:3892-3894. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ijichi H, Kawabe T, Isayama H, Yamagata M, Imai Y, Tada M, Komatsu Y, Shiratori Y, Omata M, Tanaka K, Midorikawa Y, Kubota K, Makuuchi M. "Duodenal intussusception" due to adenoma of the papilla of Vater. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1399-1402. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Saida Y, Matsueda K, Itai Y. Distal migration of duodenal tumors: simple prolapse or intussusception? Abdom Imaging. 2002;27:9-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Taams J, Huizinga WK, Somers SR. The wandering ampulla--duodenal-jejunal intussusception of a carcinoid tumour with displacement of the bile duct to the left iliac fossa. A case report. S Afr J Surg. 1992;30:153-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Marsicovetere P, Ivatury SJ, White B, Holubar SD. Intestinal Intussusception: Etiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Greenwald ES, Parker JG, Schultz S, Reed GE. Benign papillary adenoma of the ampullary region of the duodenum with intussusception. Gastroenterology. 1962;43:344-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Choi SH, Han JK, Kim SH, Lee JM, Lee KH, Kim YJ, An SK, Choi BI. Intussusception in adults: from stomach to rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;183:691-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Felson B, Levin EJ. Intramural hematoma of the duodenum: a diagnostic roentgen sign. Radiology. 1954;63:823-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iko BO, Teal JS, Siram SM, Chinwuba CE, Roux VJ, Scott VF. Computed tomography of adult colonic intussusception: clinical and experimental studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1984;143:769-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Warshauer DM, Lee JK. Adult intussusception detected at CT or MR imaging: clinical-imaging correlation. Radiology. 1999;212:853-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de Castro SM, van Heek NT, Kuhlmann KF, Busch OR, Offerhaus GJ, van Gulik TM, Obertop H, Gouma DJ. Surgical management of neoplasms of the ampulla of Vater: local resection or pancreatoduodenectomy and prognostic factors for survival. Surgery. 2004;136:994-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ceppa EP, Burbridge RA, Rialon KL, Omotosho PA, Emick D, Jowell PS, Branch MS, Pappas TN. Endoscopic versus surgical ampullectomy: an algorithm to treat disease of the ampulla of Vater. Ann Surg. 2013;257:315-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schneider L, Contin P, Fritz S, Strobel O, Büchler MW, Hackert T. Surgical ampullectomy: an underestimated operation in the era of endoscopy. HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:65-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lai JH, Shyr YM, Wang SE. Ampullectomy versus pancreaticoduodenectomy for ampullary tumors. J Chin Med Assoc. 2015;78:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |