Published online Jul 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i13.1535

Peer-review started: March 8, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Revised: May 11, 2019

Accepted: May 23, 2019

Article in press: May 23, 2019

Published online: July 6, 2019

Processing time: 124 Days and 7.2 Hours

Intracranial pressure monitoring (ICP) is based on the doctrine proposed by Monroe and Kellie centuries ago. With the advancement of technology and science, various invasive and non-invasive modalities of monitoring ICP continue to be developed. An ideal monitor to track ICP should be easy to use, accurate, reliable, reproducible, inexpensive and should not be associated with infection or haemorrhagic complications. Although the transducers connected to the extra ventricular drainage continue to be Gold Standard, its association with the likelihood of infection and haemorrhage have led to the search for alternate non-invasive methods of monitoring ICP. While Camino transducers, Strain gauge micro transducer based ICP monitoring devices and the Spiegelberg ICP monitor are the emerging technology in invasive ICP monitoring, optic nerve sheath diameter measurement, venous opthalmodynamometry, tympanic membrane displacement, tissue resonance analysis, tonometry, acoustoelasticity, distortion-product oto-acoustic emissions, trans cranial doppler, electro encephalogram, near infra-red spectroscopy, pupillometry, anterior fontanelle pressure monitoring, skull elasticity, jugular bulb monitoring, visual evoked response and radiological based assessment of ICP are the non-invasive methods which are assessed against the gold standard.

Core tip: Although, over the last few decades, intracranial pressure monitoring (ICP) monitoring has become the standard of care, invasive methods are a health-resource intensive modality and are associated with chances of haemorrhage and infection. In terms of accuracy and reliability, the intraventricular catheter systems still remain the gold standard modality. Recent advances have led to the development of non-invasive techniques to monitor ICP, but further evidence is needed before it becomes an alternative to invasive techniques. Apart from primary brain injury due to raised ICP, secondary brain injury can occur due to ongoing micro and macro vascular dysfunction in the face of apparently normal ICP.

- Citation: Nag DS, Sahu S, Swain A, Kant S. Intracranial pressure monitoring: Gold standard and recent innovations. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(13): 1535-1553

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i13/1535.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i13.1535

The concept of monitoring the intracranial pressure (ICP) as an indicator of dysfunc-tional intracranial compliance can be thought to be a practical approach to a historical doctrine proposed by Monroe and Kellie centuries ago[1-3]. Simplistically, Monroe and Kellie likened ICP to a mild positive pressure created by the brain, cerebral blood volume and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in a semi-rigid skull box. These components normally compensate for changes in each other, however, when this compensatory reserve is exhausted, potentially catastrophic neurological sequelae of intracranial hypertension occurs. Such perturbations of intracranial compliance occur in a variety of brain insult pathologies such as traumatic brain injury (TBI), intracranial space occupying lesions (ICSOL), intracranial heamorrhage (ICH) and subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH). Hence, monitoring of intracranial pressure assumes importance in the aforementioned diverse neurologically injured population as an indication for commencement of ICP control measures as well as in risk stratification, prognosti-cation and assessing response to therapy.

ICP monitoring as a novel modality was introduced to the medical fraternity by Guillaume and Janny in 1951[4]. However, the credit of popularizing ICP monitoring goes to Lundberg and his colleagues who systematized and established the protocol for its use in 1960[5]. ICP monitoring was more of a research tool for the ensuing three decades till its use in neurointensive care became an established practice following recommendations for its use in brain trauma foundation guidelines which were first published in 1995 and subsequently modified in 2016[6-9].

The aim of this review is to establish the pathophysiological basis of ICP moni-toring, the physicality of such monitoring, the various brain injury states where it is used as well as a look at the armamentarium of modalities now available to have an idea about intracranial compliance. We also take a look at the evidence for the usefulness of such monitoring in clinical practice in terms of influencing outcome and sequelae in brain injured patients.

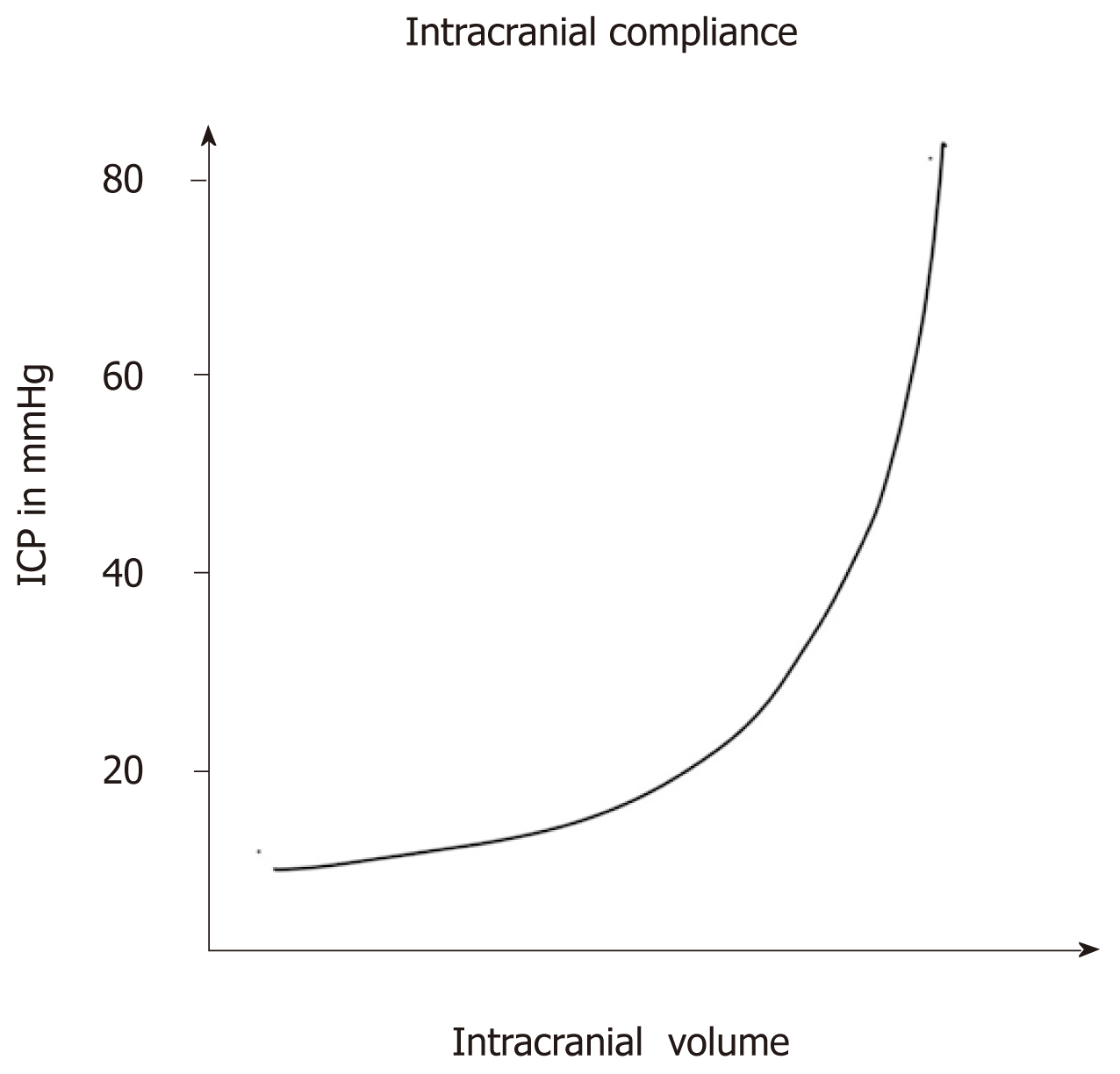

As is evident from the already discussed Monroe-Kellie doctrine, there is an existing volume of reserve in the brain which is around 60-80 mL in young persons and approximately 100-140 mL in geriatric population[10]. This surprising paradox in intracranial compliance can be explained by ongoing cerebral atrophy with age. The volume pressure curve denoting the relationship between ICP and intracranial volume is depicted in the Figure 1. The normal values of ICP are elucidated in the Table 1.

| Age group | ICP value in mm of Hg |

| Adults (supine) | 5 – 15 |

| Children | 3 – 7 |

| Infants | 1.5 – 6 |

When pathological conditions cause an increase in intracranial volume, the initial intracranial volume expansion till 30 mL is well compensated by CSF and venous blood movement out of the cranial vault. The compressibility of the constituents which are expanding determines the final intracranial compliance. For example, blood and CSF excess in the brain (intracranial haemorrhage and hydrocephalous) results in a steep curve owing to their incompressible nature. The volume pressure relationship is much more gradual when compressible brain parenchyma is involved (tumours and ICSOLs).

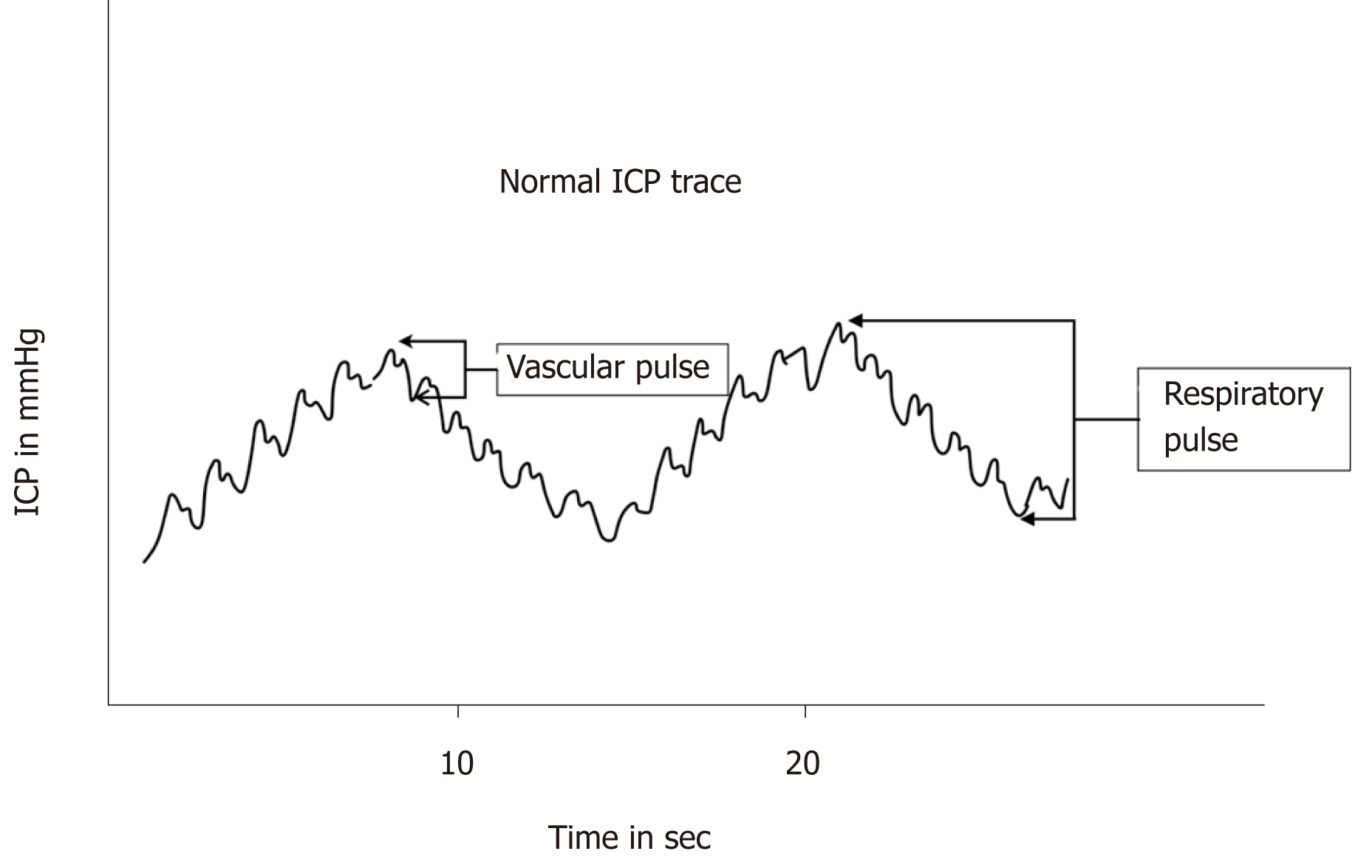

The intracranial pressure waveform is pulsatile in nature and correlates with respira-tory and cardiac cycle (Figure 2). The amplitude of the respiratory waves varies between 2 to 10 mmHg. The wave mirrors changes in intrathoracic pressure with respiration and increases in ICP obliterate the variation in amplitude. The cardiac component of the ICP wave correlates with pressure dynamics and its amplitude varies between 1 to 4 mm of Hg (Figure 2).

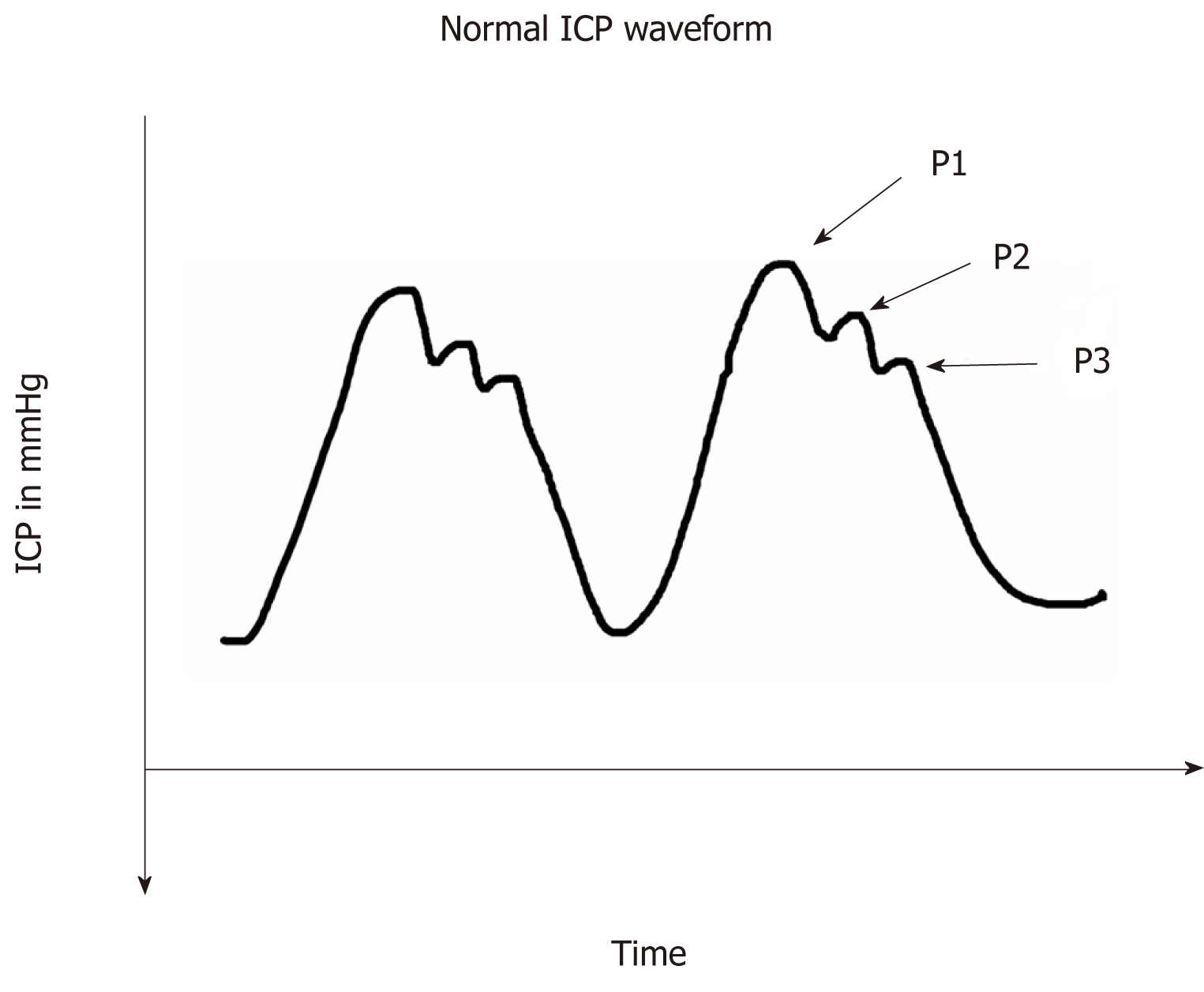

The different waves in the vascular ICP waveform are depicted in Figure 3. P1 wave (Percussion wave) reflects the arterial pulses of the carotid plexus into the CSF. P2 wave (Tidal wave) is thought to represent ICP proper as a correlate of the arterial pulses reflected off the brain parenchyma. The P3 wave (Dicrotic notch) reflects aortic valve closure.

Attempts have been made by Hammar et al[11] to use the morphology of the ICP pulse wave as a surrogate marker of intracranial elastance. They decided that the systolic part of the vascular ICP waveform reflects arterial activity while the caudal descending segment denotes the pressure in SVC. Hence when the ICP increases the caudal part of the ICP waveform (the P2 component) assumes the shape of an arterial pulse and when there is CVP elevation, the waveform approximate a venous pulse.

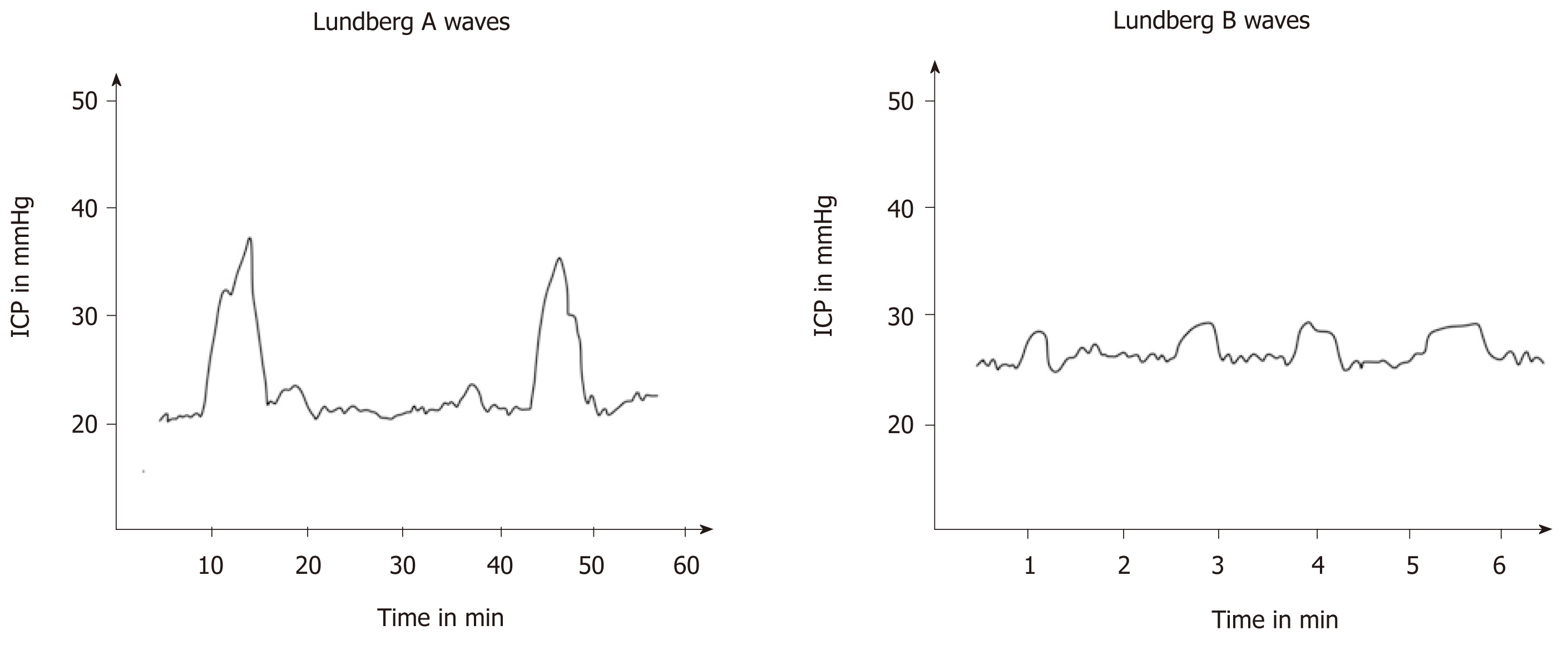

When the ICP is elevated, the vascular (cardiac) waveform amplitude increases while the respiratory waveform amplitude decreases. Other phenomena which are visible in dysfunctional intracranial compliance include occurrence of P waves as well as elevation of P2 and rounding off of the waveform (Figure 4). The occurrence of these phenomena are useful in clinical practice in that these alert the neurophysician to initiate ICP control measures on an urgent basis. It is pertinent to note here that increased ICP can produce characteristic waveform variously classified by Lundberg into A, B and C waves[12].

Lundberg A waves are the ones which denote highest rise in ICP (50-100 mmHg). They are generally indicative of high degree of cerebral ischemia and impending brain herniation and persist for 5 to 10 min (Figure 5).

Lunenburg B waves occur for a lesser period of time (1 to 2 min), the ICP elevation or not as much, 20 to 30 mm Hg, and are rhythmic in nature. They indicate evolving cerebral injury causing a gradual increase in ICP (Figure 5)[13,14]. Lundberg C waves correlate with blood pressure fluctuations brought about by baroreceptors and chemoreceptor reflex mechanisms and have no clinical significance.

The basic idea of the utility of ICP monitoring lies in utilizing it as a means of predic-ting and preventing inordinate cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and the relationship between the two in the given formula: CPP = mean arterial pressure (MAP) – ICP.

The role of CPP has been reinforced over the last two decades. Earlier, dehydrating the brain was considered sacrosanct to the management of brain injured states. With the evidence of cerebral ischemia playing a central role in secondary brain injury, CPP maintenance has now assumed a more central role[15]. However, there are certain caveats to CPP guided management of brain injury. Overzealous attempts to maintain CPP has resulted in cerebral hyperemia and vasogenic edema, especially in non-reactive cerebral vasculature. Such means also put an inordinate stress on the myocardial functioning of such patients resulting in heart failure and attendant cardio-respiratory perturbations. In the light of aforementioned complications, recent evidence has witnessed a paradigm shift from the initial CPP aim of 70 mm Hg to an easily attainable and safer CPP of 60 mm of Hg[16,17]. A bone of contention in ICP monitoring is whether efforts to keep ICP below a certain value were actually benefi-cial to the outcome or not. The initial thinking was that as long as the CPP was taken care of, intracranial pressure was of no consequence[18].

However, studies debunked this logic, showed increased ICP had inherent toxic effects on the brain independent of perfusion, and large trials established 20 mm Hg as the cut off for intracranial hypertension[19]. Newer evidence in the most recent Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines have pushed this cut off higher to 22 mm of Hg[9].

ICP monitoring has been variously explored as a diagnostic and therapeutic modality in various pathological conditions culminating in neurological injury (Table 2). There is a paucity of evidence currently to formulate universally excepted guidelines. However, indications for ICP monitoring in current clinical practice are often institu-tion and neurophysician specific[20-23]. Traumatic brain injury is a neurological injury subset in which there has been substantial amount of work as far as ICP monitoring is concerned. The American Brain Trauma Foundation (BTF) guidelines set out clear indications for ICP monitoring in TBI. In patients with severe TBI with a normal CT scan, ICP monitoring is indicated if two or more of the following features are noted at admission: (1) Age over 40 years, (2) Unilateral or bilateral motor posturing, or (3) Systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg[9]. Based on the quality of evidence available (one Class 1, four Class 2 and nine Class 3 studies) the foundation recommends (Level II B) the use of ICP monitoring in patients of TBI to reduce in-hospital and 2-wk post-injury mortality[9]. A pertinent thing to note is that the new BTF guidelines set 22 mm Hg as the lower limit for intracranial hypertension while the limit in the previous guidelines was 20 mmHg[9]. In addition, it is important to consider that for ICP monitoring, it is also important to consider the most useful location of the ICP monitor as well as the impact of local intracranial pressure gradients.

| Indications |

| Traumatic brain injury |

| Haemorrhage |

| - Intracranial haemorrhage |

| - Subarachnoid haemorrhage |

| Cerebral edema |

| Cerebral abscess |

| Hydrocephalus |

| Hepatic encephalopathy |

| Cerebral ischaemia |

Regarding local pressure gradients in the brain, it is relevant to note that these exist even in physiological conditions. There have been studies across a wide spectrum of pathologies causing neurological injury like SAH, TBI, hydrocephalus and ICH[24-27]. Studies have revealed that amongst various subsets, local pressure gradients in the brain are significant in the subset of TBI, irrespective of the presence or absence of mass lesion[28-31].

As discussed earlier, there is a plethora of ICP monitoring devices, both invasive and non-invasive[32]. The multitude of devices and technology available for ICP monitoring has necessitated formulation of minimum standards for an ICP monitor. (1) The device pressure range should be between 0 to 100 mm Mercury; (2) Its accuracy should be ± 2 mm Mercury in the range of 0 to 20 mm Mercury; and (3) In the pressure range of 20-100 mm, the maximum allowable error Hg should be 10%.

An ideal monitor to track ICP should be easy to use, accurate, reliable, reprodu-cible, inexpensive and should be associated with minimal infections and haemorrhagic complications. Amongst all devices, EVD systems are presently considered as the benchmark devices to monitor ICP. Invasive transducers are reliable and accurate; however cost and access to technology are pressing issues limiting their widespread use. Subarachnoid, epidural and subdural locations are currently out of favor. Intraparenchymal pressure monitoring systems are relevant in slit like ventricles (paediatric age group) and swollen brain conditions. Infections and hemorrhagic complications are associated with invasive monitoring modalities and have been responsible for driving a lot of technology search for non-invasive modalities. The other major reasons why non-invasive ICP monitoring technology has evolved so much research interest is to discover a logistically and financially lighter alternative to invasive ICP modality without sacrificing the reliability, accuracy and reproducibility of invasive methods.

The credit for demonstrating the feasibility of measuring intracranial pressure invasively goes to Lundberg way back in 1960[5]. There has been an advent of various methods of monitoring ICP directly since then and each of them has its own unique set of shortcomings and desirable properties.

It is pertinent to note that intraventricular catheters and parenchymal micro-transducers are the techniques which are most commonly used in present day neuroscience specialties and hence will be discussed in more detail in our review.

The idea of placing a catheter directly into the ventricles through a burr hole is a very simple but effective premise in terms of reliability. So much so that, this method though the oldest of the described technique, still remains the gold standard to measure intracranial compliance and also to standardize other methods of measure-ments[20,32-36].

The technique, also known as the EVD technique, consists of connecting the cath-eter in either of the ventricles with an external strain gauged fluid coupled device. Such an assembly offers the advantage of re-calibration. While the reference point for such calibration ideally should be the Foramen of Monroe, normally the external auditory meatus is chosen as the anatomical landmark for convenience. In addition to monitoring ICP, EVD placement offers additional advantage in the form of facilitating therapeutic drainage of CSF, intrathecal administration of drugs (antibiotics, thrombolytics) and drainage of Intraventricular hemorrhage. However, in some cases, therapeutic CSF drainage especially in the presence of concomitant intracranial space occupying lesion has been associated with cerebral herniation[37-39].

The traditional approach for EVD placement has been classically through the coronal burr hole approach, however based on individual neurosurgeon’s prefe-rences, other sites can be chosen as well[40]. Either the ipsilateral lateral ventricle or the third ventricle is the preferred site and owing to its non-dominance in the majority of the population[41]. Misplacement of the catheters (extraventricular, parenchymal) have been reported as has been inadvertent injury to cerebral structures such as basal ganglia, thalamus, internal capsule[42-44]. Kinks, bubbles, clots, tissue debris as well as infectious complications because of repeat surgery also pose a common impediment in the accurate recording of an ICP waveform and should be routinely screened for[45,46].

Technically EVD placement may be challenging in patients of young age group owing to narrow ventricular system. In contrast, atrophy induced widened ventricu-lar systems in older age groups also cause difficulty in placement of EVD[5]. Though it appears to be an innocuous surgical procedure, haemorrhage and infectious complications are common. While the incidence of haemorrhage is variably high in different case series, detection of haemorrhage was more in institutions routinely performing CT scans after the procedure[47]. Thankfully significant haemorrhage causing morbidity and mortality occur only in fewer proportion of patients (0.9 – 1.2%)[42,47,48].

Similar to haemorrhage, infectious complications following EVD placement show a wide reported variance amongst studies (1%-27%)[49,50]. The spectrum of infectious complications range from self-limiting indolent skin site infections, infections of the meninges and ventricular systems of the brain to florid and often fatal septi-cemia[42,49,50]. Intra-ventricular haemorrhage, sub-arachnoid haemorrhage, CSF contamination following a breach in the bony cranial vault, as well misplacement of EVD are other factors predisposing to EVD related infectious complications[43-45,50]. Various modalities such as use of antibiotic and silver impregnated catheters, subcutaneous placement of catheters, minimal mechanical disruption of the EVD setup, shortening use of EVD to less than five days and use of sterile techniques in an operating room setup have been shown to reduce infection rates[46,49,51-54]. At present evidence does not support the routine change of catheters or prophylactic antibiotics and it seem prudent to refrain from sampling CSF on a routine basis[46,50].

To summarize, EVD placement in the ventricle remains a highly reliable option for measuring intracranial compliance making it a gold standard technique. Care should be taken to minimize morbidity of infections and haemorrhagic complications as well as mechanical disruption in the catheter setup.

Other modality to directly monitor ICP in the present era of neurosciences uses the giant strides in micro-transducer technology. There are various kinds of devices, for example, fibreoptic strain gauge and pneumatic sensor devices which use the aforementioned technology, and an attempt has been made to present information about them in order of popularity, level of evidence and other salient points precluding their use. Numerous anatomic locations such as brain parenchyma, epidural and subdural spaces as well as the subarachnoid space have been explored to monitor ICP. The most common location of placement of microtransducers in the routine practice is the right frontal cortex parenchyma, although other sites are also selected in brain parenchyma depending on loco-regional pathology in the brain[42].

Micro-transducers have exhibited a good deal of correlation with intraventricular devices. They offer advantage over EVD in ease of handling and the fact that readings are not influenced by patient positions. The absence of fluid coupled system ameliorates the risk of infection and simplicity in the surgical maneuvering required for placement translates to lesser haemorrhagic complications. Also, the incidence of pressure waveform damping and measurement artefacts is lesser than fluid coupled devices such as EVD[42,55].

In addition to the drift in the system which sets in on prolonged use, the limitations with intraparenchymal transducer technology include an inability to recalibrate, institute concomitant CSF drainage as well as inability to predict global ICP [55].

This consists of a fibreoptic transducer which uses a diaphragm and a microprocessor driven amplifier to detect changes in light signal intensity to calculate ICP and represent it both as a waveform and a number[56]. The catheters are single use, involves an expensive set up and prone to damage during insertion in uncooperative patients. A daily baseline drift of about 0.3 mm Hg occurs routinely[56-58]. Available evidence suggests that the significant infectious and haemorrhagic manifestations are negligible[57,59].The technical errors have been mostly attributed to dysfunctional fibreoptic cables[56,57].

The commonly used Codman microsensor, the Raumedic Neurovent-P and S type sensors and the most recent Pressio sensor all work on the piezoelectric strain gauze technology[42].

Codman microsensor is a popular device and extensive studies have established it as a robust, stable and accurate ICP monitoring system which affords therapeutic options of CSF drainage when used in conjunction with the ventricular catheter[55]. Its small size permits its use in the pediatric age group as well as at various anatomical sites. There is no need for alignment and zeroing, and most importantly, infection and haemorrhagic complications and negligible[60-62]. The other two recent piezo-electric sensors, Raumedic Neurovent-P and S type and Pressio sensor have demonstrated similar efficacy and safety profile[63,64]. Drift continues to remain a common problem across all three devices, however newer devices have performed better in comparison to the Codman set up[61,63,65-68].

These ICP monitors use pneumatic strain gauze technology in a balloon tipped catheter system to measure ICP mostly at subdural or epidural location[69]. Available evidence has shown compatible results to gold standard intraventricular and intraparenchymal EVD-based monitors with negligible infections and haemorrhagic complications[69-71]. The fact that recent versions allow for therapeutic CSF drainage and have facilities for periodic automatic drift correction, besides being cheaper than the microtransducers, have made these compliance monitors very popular in neuro critical care set up[55].

The idea of a non-invasive method of measuring intracranial pressure is captivating, as at least theoretically, they are expected to be less cumbersome and would avoid complications such as haemorrhage and infection. Additionally, in certain clinical scenarios or patient conditions, non-invasive monitoring should be logically a more reliable alternative. The advent of recent software-based neuro-imaging techniques and new diagnostic tools has led to the development of a variety of methods which have been investigated for their potential to replace the gold standard invasive monitoring. Ideally a non-invasive ICP Monitor should be readily available throughout the hospital, be inexpensive, accurate and should also be simple and convenient to use. There should be minimal contraindications and limitations, so that it can be of use in all patient populations. There have been various attempts at classi-fying non-invasive ICP monitors. While some authors have classified according to the anatomical location of the measured entity, some have classified it according to the timeframe utilized. We have attempted to present the various modalities for non-invasive ICP monitoring in terms of relevance and popularity of use.

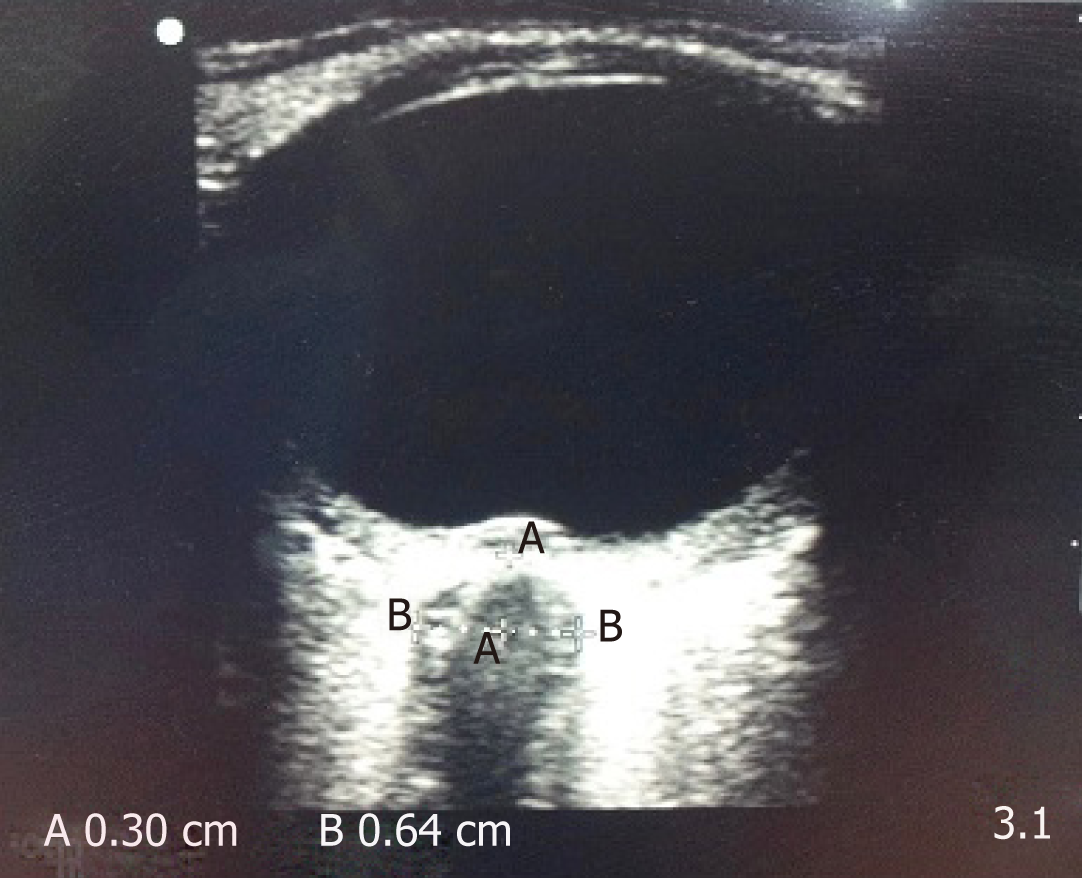

Measuring the optic nerve she diameter as a mirror of ICP works on the premise that the intracranial cavity is in direct continuation with the CSF filled subarachnoid space between optic nerve and the sheath which encloses the optic nerve[72,73]. Hence the logical extension would be that an increase in CSF pressure would expand the sheath and this change would be dynamic. It presents neuroscientists an unique window to measure the optic nerve sheath diameter (ONSD) which would predict dysfunctional intracranial compliance in real time[74]. It is measured by placing a liner transducer probe (13-7.5 MHz) over the closed eyelid to obtain an image of the optic nerve sheath as a hypodense area behind the globe of the eye (Figure 6). The ONSD is measured at a depth of 3 mm from the posterior pole of the eyeball as this point is the most reflective of the changes in ICP[75]. While sonographic ONSD measurement is easy to learn and non-cumbersome, it has certain limitations. It is contraindicated in clinically commonly encountered lesions such as tumors of the orbit, inflammation of eye, sarcoidosis (one of the leading causes of inflammatory eye disease), Graves’ disease, diseases affecting the optic nerve sheath diameter and patients with legions of the optic nerve[42] . Despite the limitations, measurement of ONSD has been established as a useful bedside modality to predict increased intracranial pressure and there have been a slew of studies in neuroanaesthesia and neuro-intensive care to establish that ONSD is of actual utility in the management of intracranial hypertension. While it has been established that an ONSD increase in millimeters corresponds to dramatic changes in ICP value, is it still has a long way to go to replace invasive ICP monito-ring in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Available evidence suggests an ONSD of 4.5 to 5.5 mm to be indicative of intracranial hypertension[75-85]. In clinical settings, ONSD has established itself as a reliable screening tool for detection of severe ICP changes [76,86,87].

Hence, while currently ONSD might not be a highly sensitive and specific mo-dality, it is more popular as a screening tool for detecting increased ICP, especially in situations where access to invasive monitoring techniques are unavailable.

The idea to measure central retinal vein pressure as a surrogate of ICP was mooted by Baurmann way back in 1925[88]. However it was only at the turn of the last century that Firsching et al[89] explored the idea in a study. They concluded that CRV pressure measurement or ophthalmodynamometry showed good correlation with invasive ICP monitoring but it was not useful for continuous monitoring. Subsequent studies by the same author, Firsching et al[90], have demonstrated refined algorithm-based measurement and superior technology whilst using ODM. Although venous ophthalmodynamometry can be useful for static measurements, it cannot be used for continuous monitoring[90]. While it can predict raised ICP with a probability of 84.2%, in 92.8% of patients, a normal central retinal vein pressure indicates normal ICP[90]. However, while it has been established that ophthalmodynamometry is an exciting non-invasive modality, it still remains inferior to invasive ICP monitoring [90].

The core concept of using tympanic membrane displacement (TMD) as a simulation of ICP is based on the proximity of the stapes and the oval window. The assumption is that the cochlear fluid pressure which would logically be a function of the ICP would affect the stapedial excursions. Consequently the TMD, which can be measured in response to auditory stimulation, would present an insight into intracranial pressure dynamics[78,91]. Available evidence for TMD and tympanic membrane infrasonic emissions has shown them to be a good screening tool which can be useful in assessment and follow-up of patients with increased ICP. However, they do not allow the establishment of specific ICP values and there are certain prerequisites for the test, such as intact stapedial reflexes, normal middle ear pressure and a patent cochlear aqueduct[78,92-94].

This novel ultrasound technique was developed by Michaeli et al[95] and they used the tissue specific ultrasound resonance of the brain to digitally obtain an echopulsogram which showed good correlation with invasive ICP. However, following the initial promise, there have been very few studies, and hence, the level of evidence is pretty poor.

Numerous studies have attempted to correlate intraocular pressure with intracranial pressure. However majority of the studies have unequivocally proved that tonometry IOP has very poor correlation with ICP. Present literature does not support it as a form of non-invasive modality of ICP monitoring[96-102].

In a one of its kind experimental model in 2013, Wu et al[103] attempted to use ultra-sound autoelasticity of the brain to predict ICP. Whereas the correlation in the experimental model was acceptable, follow up studies to validate the same in human populations are lacking.

As discussed earlier on the segment of TMD, on account of the continuity of CSF with perilymphatic space, ICP changes can affect otoacoustic emissions from the middle ear[104,105]. A form of otoacoustic emission named as Distortion-Product Oto-Acoustic Emissions has consequently been tested as a non-invasive ICP monitor[103,104,106-108]. Studies correlating DPOE with ICP have shown good correlation in experimental models. Results in human population have vindicated a good correlation with inva-sive methods[105,106,109,110].

Trans cranial doppler (TCD) as a tool to monitor ICP was first described by Klingelhöfer et al[111,112] and basically made use of the TCD derived velocities for predicting intracranial compliance. The MCA is commonly used for insonation and different indices such as Pourcelot resistance index and Gosling's pulsatility index have been explored to correlate with ICP. Gosling's index has been favored primarily because it remains unaffected by extraneous factors such as angle of insonation.

The fact that TCD is extensively used in neurosciences has spawned a lot of studies exploring the reliability in terms of correlation with ICP [113-116]. Studies by Bellner et al[116] in 2004, and more recently by Wakerley et al[117] in 2014 showed a good correlation between ICP and TCD values, especially at higher values (ICP more than 20). Wakerley et al[117] in fact went a step further and developed a formula to predict ICP using PI –ICP = 10.93 X PI – 1.28.

However, this formula still needs validation by further independent studies. Considerable TCD based studies have shown ambiguous results. Reviews by some researchers have even questioned the clinical usefulness of this modality to monitor ICP[78,114,118]. Similar non-encouraging results have been observed in the paediatric population[119]. Hence while TCD shows initial promise as a surrogate marker its routine use as a non-invasive ICP monitor is contentious.

The neurophysiological premise on which electro encephalogram (EEG) has been explored to predict ICP is that EEG would change if there are changes in CMRO2 which gets affected in dysfunctional intracranial compliance[120]. Numerous studies have explored the aforementioned concept and Amantini et al[121,122] showed that neurophysiology changes actually preceded ICP changes[120-122]. Recently Chen et al[123] established certain components of EEG power spectrum analysis to be useful in correlating with ICP prediction. Further studies are warranted to establish the correlation of EEG spectrum analysis with ICP monitoring.

Near infra-red spectroscopy (NIRS) is a newly emerging technology which works on the principle of differential absorption of light in the vicinity of the infrared spectrum to detect concentration changes in oxygen and deoxyhaemoglobin. In head injured patients NIRS has been found to detect alterations in cerebral blood flow, cerebral blood volume, brain tissue oxygenation and ICP[124,125]. Wagner at all also established a correlation of ICP with an NIRS in children with severe encephalopathy however the level of evidence for such correlation remains poor[78,126].

Way back in 1983, Marshall at al[127] established the fact that an oval pupil was indicative of high ICP suggestive of imminent brain herniation. They did not indicate any numerical value of ICP correlating with pupillary changes. Advancement of technology resulted in another study by Taylor et al[128,129] using the novel use of a pupillometer. This established that pupillary constriction velocity is sensitive to high ICP and a 10% decrease in pupil size was associated with intracranial hypertension (ICP more than 20 mm Hg) in all cases. Recently Chen et al[130,131] introduce the concept of neurological pupillary index using an algorithmic approach to predict ICP with pupillary reactivity. While they conclusively proved that an inverse association between ICP and pupillary reactivity exists, a direct correlation to actual ICP values were not forthcoming. Hence, present day evidence suggests that while pupillometer can predict and screen for patients with dysfunctional intracranial compliance, it is inappropriate for continuous ICP monitoring.

In infants, the anterior fontanelle is open and presents as a window to measure ICP. Preliminary studies to explore this were done in the previous century, but they were largely ambiguous because of unsuccessful fixation of the device[132-135]. Over the years, various devices such as the Rotterdam transducer, the Fontogram and the Ladd Intracranial Pressure Monitoring device has been used to measure anterior fontanelle pressure and various levels of reliability have been reported with respect to correlation with ICP[133-136]. However, currently none of these modalities are being routinely used. A definite review by Wiegand et al[137] has made it clear that ICP monitoring in infants is currently not feasible by non-invasive methods.

The notion that measuring the minute expansion of the skull as a reflection of increasing ICP has been explored in animal studies and cadavers in 1985 by Pitlyk et al[138]. However, the technology which they used could not be further[138]. Yue et al[139] showed a positive correlation between increasing ICP and skull deformation. However, the concept of skull elasticity as a non-invasive modality of ICP monitoring is still in its infantile stages[139,140].

York et al[141] have demonstrated a good relationship between intracranial pressure elevation and a shift in latency of the N2 wave of the visual evoked response. The N2 wave is normally found at 70 ms and is thought to be a cortical phenomenon. It is therefore likely to be sensitive to potentially reversible cerebral cortical insults such as ischemia or increased intracranial pressure.

There have been numerous attempts to develop ICP and mortality prediction models based on CT findings such as loss of gray and white matter differentiation, midline shift and basal cistern and ventricular effacement[79,142-143]. However, present evidence suggests that CT is not a very sensitive tool in the sense that CT remains normal even with a raised ICP [144].

The MRI-ICP method is a new method wherein advances in MRI technology are combined with neurophysiological principles to predict ICP[145]. It basically measures the pulsatile differences in intracranial volume and pressure to predict a mean ICP.

MRI has also been used to evaluate the optic nerve and measure the optic nerve sheath diameter 3 mm posterior to the globe[146]. However, MRI based techniques suffer from obvious lacunae in the form of offering only picture of ICP at a particular time frame. Also, MRI based techniques require the patient to be subjected to transport logistics and the convenience of bedside procedures is absent[147].

Over the last few decades, ICP monitoring has become the standard of care, especially in Europe and North America. However, the invasive methods are a health-resource intensive modality necessitating the question to be asked – does ICP monitoring really make a difference in outcomes and is this outcome different from therapeutic decisions based on clinical evaluation. The landmark BEST – ICP trial explored this question and the implications of this trial are particularly interesting[148,149]. This multicentre trial in Bolivia and Ecuador compared two management strategies in patients with severe TBI. In one arm management decisions and treatment were standardized based on invasive ICP monitoring while in the other arm treatment strategies was based on serial CT and clinical features. The results showed that while there was trend towards lesser mortality and better care in ICP monitoring group, in terms of outcome both modalities achieved the same results. While it remains a landmark trial, the BEST – ICP trial has attracted a lot of critique, bringing to light several limitations of the study[150-152].

It is important to note that the trial is not a direct measure of efficacy of ICP monito-ring. When looked at it closely, it was basically a trial of two management strategies, the management strategy of ICP monitoring being a novel one. Further, there was no set limit for intracranial hypertension in ICP monitoring group to institute therapy[148,149]. This trial has established the need for further research into the topic. Further research would most likely be comparative effectiveness research because the practical scope of conducting randomized controlled trials in the complex, volatile and ever-changing settings of neuro-critical care is very limited[153,154]. It has also been suggested that there could be more to what that meets the eye in secondary brain injury, especially ongoing micro and macro vascular dysfunction in the face of apparently normal ICP, CPP and cerebral blood flow[148,155-163].

An important implication to consider is the oversimplification to treat elevated ICP as a number: 20 mm Hg earlier, and 22 mm Hg now, especially in TBI[16,164,165]. There is more and more evidence emerging which suggests that cerebral cellular dysfunction and hypoxia at presumably normal ICP. This brings to fore the concept of multi-modality management[155,166-170]. Along with ICP monitor, new-age monitors such as cerebral microdialysis, brain tissue saturation, TCD, cerebral blood flow, EEG as well as routine imaging based monitoring have been explored to monitor neurological injury[171-174]. They are rapidly establishing themselves as a part of multimodality management where in addition to understanding the pathophysiology of ongoing neurological injury and influencing therapeutic decisions, they also have shown promise as independent markers of morbidity and mortality[175-180].

Hence, while ICP monitoring has been shown to have beneficial effects in neurologically injured patients, to get better outcomes, it would be wise to use it in conjunction with other monitors of the brain.

ICP monitoring has established itself as a modality useful in predicting outcome and guiding therapy across the whole spectrum of neurologically injured patients. In terms of accuracy, reliability and therapeutic options, the intraventricular catheter systems still remain the gold standard modality. However, recent advances in technology and software have meant that non-invasive techniques to monitor ICP have become more relevant. There is still a considerable way to go before non-invasive modalities of ICP monitoring becomes more popular and a widespread alternative to invasive techniques.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: India

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Alexopoulou A, Garbuzenko DV S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A E-Editor: Wang J

| 1. | Monro A. Observations on the structure and function of the nervous system. Edinburgh: Creech and Johnson, 1783. . |

| 2. | Kellie G. An account of the appearances observed in the dissection of two of the three individuals presumed to have perished in the storm of the 3rd, and whose bodies were discovered in the vicinity of Leith on the morning of the 4th November 1821 with some reflections on the pathology of the brain. Transac Medico Chirurg Soc Edinburgh 1824; 1: 84–169. . |

| 3. | Cushing H. The third circulation in studies in intracranial physiology and surgery. London: Oxford University Press 1926; 1-51. |

| 4. | Guillaume J, Janny P. [Continuous intracranial manometry; importance of the method and first results]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1951;84:131-142. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lundberg N. Continuous recording and control of ventricular fluid pressure in neurosurgical practice. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1960;36:1-193. [PubMed] |

| 6. | The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Indications for intracranial pressure monitoring. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:479-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Intracranial pressure treatment threshold. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:493-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Recommendations for intracranial pressure monitoring technology. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17:497-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carney N, Totten AM, O'Reilly C, Ullman JS, Hawryluk GW, Bell MJ, Bratton SL, Chesnut R, Harris OA, Kissoon N, Rubiano AM, Shutter L, Tasker RC, Vavilala MS, Wilberger J, Wright DW, Ghajar J. Guidelines for the Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury, Fourth Edition. Neurosurgery. 2017;80:6-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1786] [Cited by in RCA: 2216] [Article Influence: 277.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Gjerris F, Brennum J, Paulson OB, Gjerris F, Sørensen PS. The cerebrospinal fluid, intracranial pressure and herniation of the brain. Paulson OB, Gjerris F, Sørensen PS. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. Copenhagen: FADL’s Forlag Aktieselskab 2004; 179–196. |

| 11. | Hamer J, Alberti E, Hoyer S, Wiedemann K. Influence of systemic and cerebral vascular factors on the cerebrospinal fluid pulse waves. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:36-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lundberg N, Troupp H, Lorin H. Continuous recording of the ventricular-fluid pressure in patients with severe acute traumatic brain injury. A preliminary report. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:581-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Newell DW, Aaslid R, Stooss R, Reulen HJ. The relationship of blood flow velocity fluctuations to intracranial pressure B waves. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:415-421. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kjällquist A, Lundberg N, Pontén U. Respiratory and cardiovascular changes during rapid spontaneous variations of ventricular fluid pressure in patients with intracranial hypertension. Acta Neurol Scand. 1964;40:291-317. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Graham DI, Ford I, Adams JH, Doyle D, Teasdale GM, Lawrence AE, McLellan DR. Ischaemic brain damage is still common in fatal non-missile head injury. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:346-350. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Rosner MJ, Rosner SD, Johnson AH. Cerebral perfusion pressure: management protocol and clinical results. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:949-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 19.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Robertson CS, Valadka AB, Hannay HJ, Contant CF, Gopinath SP, Cormio M, Uzura M, Grossman RG. Prevention of secondary ischemic insults after severe head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2086-2095. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Young JS, Blow O, Turrentine F, Claridge JA, Schulman A. Is there an upper limit of intracranial pressure in patients with severe head injury if cerebral perfusion pressure is maintained? Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E2. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Juul N, Morris GF, Marshall SB, Marshall LF. Intracranial hypertension and cerebral perfusion pressure: influence on neurological deterioration and outcome in severe head injury. The Executive Committee of the International Selfotel Trial. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 402] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Smith M. Monitoring intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury. Anesth Analg. 2008;106:240-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Singhi SC, Tiwari L. Management of intracranial hypertension. Indian J Pediatr. 2009;76:519-529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bershad EM, Humphreis WE, Suarez JI. Intracranial hypertension. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:690-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Forsyth RJ, Wolny S, Rodrigues B. Routine intracranial pressure monitoring in acute coma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD002043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cooper DJ, Rosenfeld JV, Murray L, Arabi YM, Davies AR, D'Urso P, Kossmann T, Ponsford J, Seppelt I, Reilly P, Wolfe R; DECRA Trial Investigators; Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Decompressive craniectomy in diffuse traumatic brain injury. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1493-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1063] [Cited by in RCA: 1025] [Article Influence: 73.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Bulger EM, Nathens AB, Rivara FP, Moore M, MacKenzie EJ, Jurkovich GJ; Brain Trauma Foundation. Management of severe head injury: institutional variations in care and effect on outcome. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1870-1876. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Stein SC, Georgoff P, Meghan S, Mirza KL, El Falaky OM. Relationship of aggressive monitoring and treatment to improved outcomes in severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:1105-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gerber LM, Chiu YL, Carney N, Härtl R, Ghajar J. Marked reduction in mortality in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurosurg. 2013;119:1583-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Mindermann T, Gratzl O. Interhemispheric pressure gradients in severe head trauma in humans. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:56-58. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Mindermann T, Reinhardt H, Gratzl O. Significant lateralisation of supratentorial ICP after blunt head trauma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1992;116:60-61. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Marshall LF, Zovickian J, Ostrup R, Seelig JM. Multiple simultaneous recordings of ICP in patients with acute mass lesions. In Intracranial Pressure VI. New York: Springer 1986; 184–186. |

| 31. | Sahuquillo J, Poca MA, Arribas M, Garnacho A, Rubio E. Interhemispheric supratentorial intracranial pressure gradients in head-injured patients: are they clinically important? J Neurosurg. 1999;90:16-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Brain Trauma Foundation; American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons; Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care; AANS/CNS; Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, McConnell Hammond FF, Harris OA, Hartl R, Manley GT, Nemecek A, Newell DW, Rosenthal G, Schouten J, Shutter L, Timmons SD, Ullman JS, Videtta W, Wilberger JE, Wright DW. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. VII. Intracranial pressure monitoring technology. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24 Suppl 1:S45-S54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cremer OL. Does ICP monitoring make a difference in neurocritical care? Eur J Anaesthesiol Suppl. 2008;42:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bhatia A, Gupta AK. Neuromonitoring in the intensive care unit. I. Intracranial pressure and cerebral blood flow monitoring. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:1263-1271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhong J, Dujovny M, Park HK, Perez E, Perlin AR, Diaz FG. Advances in ICP monitoring techniques. Neurol Res. 2003;25:339-350. [PubMed] |

| 36. | March K. Intracranial pressure monitoring: why monitor? AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16:456-475. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Steiner LA, Andrews PJ. Monitoring the injured brain: ICP and CBF. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:26-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kim BS, Jallo J, Loftus CM. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring and Management of Raised Intracranial Pressure. Loftus CM. Neurosurgical Emergencies, 2nd Ed. New York: Thieme 2008; 11-22. |

| 39. | Adams HP, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Clinical Cardiology Council; Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council; Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655-1711. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Bloch J, Regli L. Brain stem and cerebellar dysfunction after lumbar spinal fluid drainage: case report. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:992-994. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Greenberg MS. Handbook of Neurosurgery. 8th Ed. New York: Thieme 2016; 1504-1519. |

| 42. | Raboel PH, Bartek J, Andresen M, Bellander BM, Romner B. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring: Invasive versus Non-Invasive Methods-A Review. Crit Care Res Pract. 2012;2012:950393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 43. | Brain Trauma Foundation. ; American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons; Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care, AANS/CNS, Bratton SL, Chestnut RM, Ghajar J, McConnell Hammond FF, Harris OA, Hartl R, Manley GT, Nemecek A, Newell DW, Rosenthal G, Schouten J, Shutter L, Timmons SD, Ullman JS, Videtta W, Wilberger JE, Wright DW. Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. IV. Infection prophylaxis. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24 Suppl 1:S26-S31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Saladino A, White JB, Wijdicks EF, Lanzino G. Malplacement of ventricular catheters by neurosurgeons: a single institution experience. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:248-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Hoefnagel D, Dammers R, Ter Laak-Poort MP, Avezaat CJ. Risk factors for infections related to external ventricular drainage. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150:209-14; discussion 214. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Dasic D, Hanna SJ, Bojanic S, Kerr RS. External ventricular drain infection: the effect of a strict protocol on infection rates and a review of the literature. Br J Neurosurg. 2006;20:296-300. [PubMed] |

| 47. | Binz DD, Toussaint LG, Friedman JA. Hemorrhagic complications of ventriculostomy placement: a meta-analysis. Neurocrit Care. 2009;10:253-256. [PubMed] |

| 48. | Gardner PA, Engh J, Atteberry D, Moossy JJ. Hemorrhage rates after external ventricular drain placement. J Neurosurg. 2009;110:1021-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Beer R, Lackner P, Pfausler B, Schmutzhard E. Nosocomial ventriculitis and meningitis in neurocritical care patients. J Neurol. 2008;255:1617-1624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Lozier AP, Sciacca RR, Romagnoli MF, Connolly ES. Ventriculostomy-related infections: a critical review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:170-81; discussion 181-2. [PubMed] |

| 51. | Fichtner J, Güresir E, Seifert V, Raabe A. Efficacy of silver-bearing external ventricular drainage catheters: a retrospective analysis. J Neurosurg. 2010;112:840-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Abla AA, Zabramski JM, Jahnke HK, Fusco D, Nakaji P. Comparison of two antibiotic-impregnated ventricular catheters: a prospective sequential series trial. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:437-42; discussion 442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Harrop JS, Sharan AD, Ratliff J, Prasad S, Jabbour P, Evans JJ, Veznedaroglu E, Andrews DW, Maltenfort M, Liebman K, Flomenberg P, Sell B, Baranoski AS, Fonshell C, Reiter D, Rosenwasser RH. Impact of a standardized protocol and antibiotic-impregnated catheters on ventriculostomy infection rates in cerebrovascular patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:187-91; discussion 191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Furno F, Morley KS, Wong B, Sharp BL, Arnold PL, Howdle SM, Bayston R, Brown PD, Winship PD, Reid HJ. Silver nanoparticles and polymeric medical devices: a new approach to prevention of infection? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;54:1019-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 557] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Abraham M, Singhal V. Intracranial pressure monitoring. J Neuroanaesthesiol Crit Care. 2015;2:193-203. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Piper I, Barnes A, Smith D, Dunn L. The Camino intracranial pressure sensor: is it optimal technology? An internal audit with a review of current intracranial pressure monitoring technologies. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1158-64; discussion 1164-5. [PubMed] |

| 57. | Bekar A, Doğan S, Abaş F, Caner B, Korfali G, Kocaeli H, Yilmazlar S, Korfali E. Risk factors and complications of intracranial pressure monitoring with a fiberoptic device. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:236-240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Artru F, Terrier A, Gibert I, Messaoudi K, Charlot M, Naous H, Jourdan C. [Monitoring of intracranial pressure with intraparenchymal fiberoptic transducer. Technical aspects and clinical reliability]. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 1992;11:424-429. [PubMed] |

| 59. | Gelabert-González M, Ginesta-Galan V, Sernamito-García R, Allut AG, Bandin-Diéguez J, Rumbo RM. The Camino intracranial pressure device in clinical practice. Assessment in a 1000 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:435-441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hong WC, Tu YK, Chen YS, Lien LM, Huang SJ. Subdural intracranial pressure monitoring in severe head injury: clinical experience with the Codman MicroSensor. Surg Neurol. 2006;66 Suppl 2:S8-S13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Koskinen LO, Olivecrona M. Clinical experience with the intraparenchymal intracranial pressure monitoring Codman MicroSensor system. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:693-8; discussion 693-8. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Fernandes HM, Bingham K, Chambers IR, Mendelow AD. Clinical evaluation of the Codman microsensor intracranial pressure monitoring system. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:44-46. [PubMed] |

| 63. | Citerio G, Piper I, Chambers IR, Galli D, Enblad P, Kiening K, Ragauskas A, Sahuquillo J, Gregson B; BrainIT group. Multicenter clinical assessment of the raumedic Neurovent-P intracranial pressure sensor: a report by the BrainIT group,”. Neurosurgery. 2008;63:1152–1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lescot T, Reina V, Le Manach Y, Boroli F, Chauvet D, Boch AL, Puybasset L. In vivo accuracy of two intraparenchymal intracranial pressure monitors. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:875-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Kawoos U, McCarron RM, Auker CR, Chavko M. Advances in Intracranial Pressure Monitoring and Its Significance in Managing Traumatic Brain Injury. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:28979-28997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Stendel R, Heidenreich J, Schilling A, Akhavan-Sigari R, Kurth R, Picht T, Pietilä T, Suess O, Kern C, Meisel J, Brock M. Clinical evaluation of a new intracranial pressure monitoring device. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:185-93; discussion 193. [PubMed] |

| 67. | Al-Tamimi YZ, Helmy A, Bavetta S, Price SJ. Assessment of zero drift in the Codman intracranial pressure monitor: a study from 2 neurointensive care units. Neurosurgery. 2009;64:94-8; discussion 98-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Citerio G, Piper I, Cormio M, Galli D, Cazzaniga S, Enblad P, Nilsson P, Contant C, Chambers I; BrainIT Group. Bench test assessment of the new Raumedic Neurovent-P ICP sensor: a technical report by the BrainIT group. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2004;146:1221-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Lang JM, Beck J, Zimmermann M, Seifert V, Raabe A. Clinical evaluation of intraparenchymal Spiegelberg pressure sensor. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1455-9; discussion 1459. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Kiening KL, Schoening WN, Stover JF, Unterberg AW. Continuous monitoring of intracranial compliance after severe head injury: relation to data quality, intracranial pressure and brain tissue PO2. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17:311-318. [PubMed] |

| 71. | Kiening KL, Schoening W, Unterberg AW, Stover JF, Citerio G, Enblad P, Nilssons P; Brain-IT Group. Assessment of the relationship between age and continuous intracranial compliance. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:293-297. [PubMed] |

| 72. | Hayreh SS. Pathogenesis of oedema of the optic disc (papilloedema). A preliminary report. Br J Ophthalmol. 1964;48:522-543. [PubMed] |

| 73. | Killer HE, Laeng HR, Flammer J, Groscurth P. Architecture of arachnoid trabeculae, pillars, and septa in the subarachnoid space of the human optic nerve: anatomy and clinical considerations. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87:777-781. [PubMed] |

| 74. | Geeraerts T, Duranteau J, Benhamou D. Ocular sonography in patients with raised intracranial pressure: The papilloedema revisited. Crit Care. 2008;12:150. |

| 75. | Ballantyne SA, O'Neill G, Hamilton R, Hollman AS. Observer variation in the sonographic measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter in normal adults. Eur J Ultrasound. 2002;15:145-149. [PubMed] |

| 76. | Kimberly HH, Shah S, Marill K, Noble V. Correlation of optic nerve sheath diameter with direct measurement of intracranial pressure. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:201-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Krishnamoorthy V, Beckmann K, Mueller M, Sharma D, Vavilala MS. Perioperative estimation of the intracranial pressure using the optic nerve sheath diameter during liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:246-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Kristiansson H, Nissborg E, Bartek J, Andresen M, Reinstrup P, Romner B. Measuring elevated intracranial pressure through noninvasive methods: a review of the literature. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2013;25:372-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Miller MT, Pasquale M, Kurek S, White J, Martin P, Bannon K, Wasser T, Li M. Initial head computed tomographic scan characteristics have a linear relationship with initial intracranial pressure after trauma. J Trauma. 2004;56:967-72; discussion 972-3. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Plandsoen WC, de Jong DA, Maas AI, Stroink H, Avezaat CJ. Fontanelle pressure monitoring in infants with the Rotterdam Teletransducer: a reliable technique. Med Prog Technol. 1987;13:21-27. [PubMed] |

| 81. | Rajajee V, Vanaman M, Fletcher JJ, Jacobs TL. Optic nerve ultrasound for the detection of raised intracranial pressure. Neurocrit Care. 2011;15:506-515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 254] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Raksin PB, Alperin N, Sivaramakrishnan A, Surapaneni S, Lichtor T. Noninvasive intracranial compliance and pressure based on dynamic magnetic resonance imaging of blood flow and cerebrospinal fluid flow: review of principles, implementation, and other noninvasive approaches. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;14:e4. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Soldatos T, Chatzimichail K, Papathanasiou M, Gouliamos A. Optic nerve sonography: a new window for the non-invasive evaluation of intracranial pressure in brain injury. Emerg Med J. 2009;26:630-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Soldatos T, Karakitsos D, Chatzimichail K, Papathanasiou M, Gouliamos A, Karabinis A. Optic nerve sonography in the diagnostic evaluation of adult brain injury. Crit Care. 2008;12:R67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Tayal VS, Neulander M, Norton HJ, Foster T, Saunders T, Blaivas M. Emergency department sonographic measurement of optic nerve sheath diameter to detect findings of increased intracranial pressure in adult head injury patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:508-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 292] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Sahu S, Swain A. Optic nerve sheath diameter: A novel way to monitor the brain. J Neuroanaesthesiol Crit Care. 2017;4S1:13-18. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 87. | Dubourg J, Javouhey E, Geeraerts T, Messerer M, Kassai B. Ultrasonography of optic nerve sheath diameter for detection of raised intracranial pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37:1059-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 88. | Golzan SM, Avolio A, Graham SL. Hemodynamic interactions in the eye: a review. Ophthalmologica. 2012;228:214-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Firsching R, Schütze M, Motschmann M, Behrens-Baumann W. Venous opthalmodynamometry: a noninvasive method for assessment of intracranial pressure. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Firsching R, Müller C, Pauli SU, Voellger B, Röhl FW, Behrens-Baumann W. Noninvasive assessment of intracranial pressure with venous ophthalmodynamometry. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2011;115:371-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Marchbanks RJ. Measurement of tympanic membrane displacement arising from aural cardiovascular activity, swallowing, and intra-aural muscle reflex. Acta Otolaryngol. 1984;98:119-129. [PubMed] |

| 92. | Reid A, Marchbanks RJ, Burge DM, Martin AM, Bateman DE, Pickard JD, Brightwell AP. The relationship between intracranial pressure and tympanic membrane displacement. Br J Audiol. 1990;24:123-129. [PubMed] |

| 93. | Samuel M, Burge DM, Marchbanks RJ. Tympanic membrane displacement testing in regular assessment of intracranial pressure in eight children with shunted hydrocephalus. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:983-995. [PubMed] |

| 94. | Stettin E, Paulat K, Schulz C, Kunz U, Mauer UM. Noninvasive intracranial pressure measurement using infrasonic emissions from the tympanic membrane. J Clin Monit Comput. 2011;25:203-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Michaeli D, Rappaport ZH. Tissue resonance analysis; a novel method for noninvasive monitoring of intracranial pressure. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:1132-1137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Lashutka MK, Chandra A, Murray HN, Phillips GS, Hiestand BC. The relationship of intraocular pressure to intracranial pressure. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:585-591. [PubMed] |

| 97. | Sheeran P, Bland JM, Hall GM. Intraocular pressure changes and alterations in intracranial pressure. Lancet. 2000;355:899. [PubMed] |

| 98. | Sajjadi SA, Harirchian MH, Sheikhbahaei N, Mohebbi MR, Malekmadani MH, Saberi H. The relation between intracranial and intraocular pressures: study of 50 patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:867-870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Czarnik T, Gawda R, Latka D, Kolodziej W, Sznajd-Weron K, Weron R. Noninvasive measurement of intracranial pressure: is it possible? J Trauma. 2007;62:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Golan S, Kurtz S, Mezad-Koursh D, Waisbourd M, Kesler A, Halpern P. Poor correlation between intracranial pressure and intraocular pressure by hand-held tonometry. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:1083-1087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Li Z, Yang Y, Lu Y, Liu D, Xu E, Jia J, Yang D, Zhang X, Yang H, Ma D, Wang N. Intraocular pressure vs intracranial pressure in disease conditions: a prospective cohort study (Beijing iCOP study). BMC Neurol. 2012;12:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Chunyu T, Xiujun P, Li N, Qin L, Tian Z. The Correlation between Intracranial Pressure and Intraocular Pressure after Brain Surgery. Int J Ophthalmol Eye Res. 2014;2:54-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Wu J, He W, Chen WM, Zhu L. Research on simulation and experiment of noninvasive intracranial pressure monitoring based on acoustoelasticity effects. Med Devices (Auckl). 2013;6:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Deppe C, Kummer P, Gürkov R, Olzowy B. Influence of the individual DPOAE growth behavior on DPOAE level variations caused by conductive hearing loss and elevated intracranial pressure. Ear Hear. 2013;34:122-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Voss SE, Adegoke MF, Horton NJ, Sheth KN, Rosand J, Shera CA. Posture systematically alters ear-canal reflectance and DPOAE properties. Hear Res. 2010;263:43-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Bershad EM, Urfy MZ, Pechacek A, McGrath M, Calvillo E, Horton NJ, Voss SE. Intracranial pressure modulates distortion product otoacoustic emissions: a proof-of-principle study. Neurosurgery. 2014;75:445-54; discussion 454-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Büki B, Avan P, Lemaire JJ, Dordain M, Chazal J, Ribári O. Otoacoustic emissions: a new tool for monitoring intracranial pressure changes through stapes displacements. Hear Res. 1996;94:125-139. [PubMed] |

| 108. | Büki B, de Kleine E, Wit HP, Avan P. Detection of intracochlear and intracranial pressure changes with otoacoustic emissions: a gerbil model. Hear Res. 2002;167:180-191. [PubMed] |

| 109. | Voss SE, Horton NJ, Tabucchi TH, Folowosele FO, Shera CA. Posture-induced changes in distortion-product otoacoustic emissions and the potential for noninvasive monitoring of changes in intracranial pressure. Neurocrit Care. 2006;4:251-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Sakka L, Thalamy A, Giraudet F, Hassoun T, Avan P, Chazal J. Electrophysiological monitoring of cochlear function as a non-invasive method to assess intracranial pressure variations. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2012;114:131-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Klingelhöfer J, Conrad B, Benecke R, Sander D. Intracranial flow patterns at increasing intracranial pressure. Klin Wochenschr. 1987;65:542-545. [PubMed] |

| 112. | Klingelhöfer J, Conrad B, Benecke R, Sander D, Markakis E. Evaluation of intracranial pressure from transcranial Doppler studies in cerebral disease. J Neurol. 1988;235:159-162. [PubMed] |

| 113. | Bouzat P, Francony G, Declety P, Genty C, Kaddour A, Bessou P, Brun J, Jacquot C, Chabardes S, Bosson JL, Payen JF. Transcranial Doppler to screen on admission patients with mild to moderate traumatic brain injury. Neurosurgery. 2011;68:1603-9; discussion 1609-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | de Riva N, Budohoski KP, Smielewski P, Kasprowicz M, Zweifel C, Steiner LA, Reinhard M, Fábregas N, Pickard JD, Czosnyka M. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility index: what it is and what it isn't. Neurocrit Care. 2012;17:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Behrens A, Lenfeldt N, Ambarki K, Malm J, Eklund A, Koskinen LO. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility index: not an accurate method to assess intracranial pressure. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:1050-1057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Bellner J, Romner B, Reinstrup P, Kristiansson KA, Ryding E, Brandt L. Transcranial Doppler sonography pulsatility index (PI) reflects intracranial pressure (ICP). Surg Neurol. 2004;62:45-51; discussion 51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Wakerley BR, Kusuma Y, Yeo LL, Liang S, Kumar K, Sharma AK, Sharma VK. Usefulness of transcranial Doppler-derived cerebral hemodynamic parameters in the noninvasive assessment of intracranial pressure. J Neuroimaging. 2015;25:111-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Bouzat P, Oddo M, Payen JF. Transcranial Doppler after traumatic brain injury: is there a role? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20:153-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Figaji AA, Zwane E, Fieggen AG, Siesjo P, Peter JC. Transcranial Doppler pulsatility index is not a reliable indicator of intracranial pressure in children with severe traumatic brain injury. Surg Neurol. 2009;72:389-394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Lescot T, Naccache L, Bonnet MP, Abdennour L, Coriat P, Puybasset L. The relationship of intracranial pressure Lundberg waves to electroencephalograph fluctuations in patients with severe head trauma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2005;147:125-9; discussion 129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Amantini A, Carrai R, Lori S, Peris A, Amadori A, Pinto F, Grippo A. Neurophysiological monitoring in adult and pediatric intensive care. Minerva Anestesiol. 2012;78:1067-1075. [PubMed] |

| 122. | Amantini A, Fossi S, Grippo A, Innocenti P, Amadori A, Bucciardini L, Cossu C, Nardini C, Scarpelli S, Roma V, Pinto F. Continuous EEG-SEP monitoring in severe brain injury. Neurophysiol Clin. 2009;39:85-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Chen H, Wang J, Mao S, Dong W, Yang H. A new method of intracranial pressure monitoring by EEG power spectrum analysis. Can J Neurol Sci. 2012;39:483-487. [PubMed] |

| 124. | Ghosh A, Elwell C, Smith M. Review article: cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy in adults: a work in progress. Anesth Analg. 2012;115:1373-1383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Kirkpatrick PJ, Smielewski P, Czosnyka M, Menon DK, Pickard JD. Near-infrared spectroscopy use in patients with head injury. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:963-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Wagner BP, Pfenninger J. Dynamic cerebral autoregulatory response to blood pressure rise measured by near-infrared spectroscopy and intracranial pressure. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:2014-2021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Marshall LF, Barba D, Toole BM, Bowers SA. The oval pupil: clinical significance and relationship to intracranial hypertension. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:566-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Fountas KN, Kapsalaki EZ, Machinis TG, Boev AN, Robinson JS, Troup EC. Clinical implications of quantitative infrared pupillometry in neurosurgical patients. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5:55-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Taylor WR, Chen JW, Meltzer H, Gennarelli TA, Kelbch C, Knowlton S, Richardson J, Lutch MJ, Farin A, Hults KN, Marshall LF. Quantitative pupillometry, a new technology: normative data and preliminary observations in patients with acute head injury. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 130. | Chen JW, Gombart ZJ, Rogers S, Gardiner SK, Cecil S, Bullock RM. Pupillary reactivity as an early indicator of increased intracranial pressure: The introduction of the Neurological Pupil index. Surg Neurol Int. 2011;2:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Chen JW, Vakil-Gilani K, Williamson KL, Cecil S. Infrared pupillometry, the Neurological Pupil index and unilateral pupillary dilation after traumatic brain injury: implications for treatment paradigms. Springerplus. 2014;3:548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |