Published online Jun 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1461

Peer-review started: January 28, 2019

First decision: April 18, 2019

Revised: April 24, 2019

Accepted: May 2, 2019

Article in press: May 3, 2019

Published online: June 26, 2019

Processing time: 151 Days and 16.4 Hours

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN) is a late complication of acute pancreatitis. The management of a WOPN depends on its location and on patient's symptoms. Trans-gastric drainage and debridement of WOPN represents an important surgical treatment option for selected patients. The da Vinci surgical System has been developed to allow an easy, minimally invasive and fast surgery, also in challenging abdominal procedures. We present here a case of a WOPN treated with a robotic trans-gastric drainage using the da Vinci Xi.

A 63-year-old man with an episode of acute necrotizing pancreatitis was referred to our center. Six wk after the acute episode the patient developed a walled massive fluid collection, with an extensive pancreatic necrosis, causing obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract. The patient underwent a robotic trans-gastric drainage and debridement of the WOPN performed with the da Vinci Xi platform. Firstly, an anterior ideal gastrotomy was carried out, guided by intraoperative ultrasound (US)-scan using the TilePro™ function. Then, through the gastrotomy, the best location for drainage on the posterior gastric wall was again US-guided identified. The anastomosis between the posterior gastric wall and the walled-off necrosis wall was carried out with the new EndoWrist stapler with vascular cartridge. Debridement and washing of the cavity through the anastomosis were performed. Finally, the anterior gastrotomy was closed and the cholecystectomy was performed. The postoperative course was uneventful and a post-operative computed tomography-scan showed the collapse of the fluid collection.

In selected cases of WOPN the da Vinci Surgical System can be safely used as a valid surgical treatment option.

Core tip: Trans-gastric drainage and debridement of the walled-off pancreatic necrosis is a valid surgical treatment in selected cases. The da Vinci Xi robotic platform with its increased flexibility, together with its new technologies, gives advantages in performing this surgical procedure. In particular, the new EndoWrist robotic stapler, noting the suitable thickness of the tissues between the branches, should reduce the risk of bleeding related to the cystogastrostomy. Moreover, it can be articulated with a range of 108° allowing the operator to directly control all the steps of the suture. Finally, the TilePro™ function can superimpose ultrasound imaging on the console screen, alongside the operatory field, giving high degree of precision in defining the best location for the gastrostomy.

- Citation: Morelli L, Furbetta N, Gianardi D, Palmeri M, Di Franco G, Bianchini M, Stefanini G, Guadagni S, Di Candio G. Robot-assisted trans-gastric drainage and debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis using the EndoWrist stapler for the da Vinci Xi: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(12): 1461-1466

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i12/1461.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1461

Walled-off pancreatic necrosis (WOPN), first described by Connor et al[1], is a late complication of acute pancreatitis that generally needs some interventions[2]. WOPN represents a challenging critical problem and it is still burdened by a high rate of mortality and morbidity[3]. The management of a WOPN depends on its location and on patient's symptoms. Trans-gastric drainage and debridement of WOPN represents an important surgical treatment option for selected patients[4].

While laparoscopic trans-gastric drainage of WOPN is well-described in the literature, only few cases of robotic approach have been published[5-7]. Furthermore, these described cases were all performed with the da Vinci Si platform and without the use of the TilePro™ function and the robotic EndoWrist staplers. Herein we report the case of a WOPN treated with a trans-gastric drainage and debridement using the da Vinci Xi surgical system with its tools such as the EndoWrist stapler and the TilePro™ function.

A 63-year-old man presented an acute episode of postprandial epigastric pain and vomiting.

An acute necrotizing pancreatitis was found at computed tomography (CT) scan at the time of admission. The patient was subsequently admitted to the Intensive Care Unit and underwent medical conservative treatment (nihil per os and total parenteral nutrition), with progressive normalization of pancreatic enzymes. After 6 wk the patient developed a walled massive fluid collection, with an extensive pancreatic necrosis, causing obstruction of the gastrointestinal tract.

Hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic alcohol consumption and smoking.

During the physical examination the patient presented diffusive abdominal pain. Vital signs on admission were as follows: temperature was 37.2 °C, heart rate was 94 beats per minute (bpm), initial blood pressure was 115/70 mmHg. In addition, his lungs and heart were found to be normal by auscultation. He always remained cardiovascularly stable.

Abnormal laboratory data at time of admission of complete blood count were as follows: RBC 3.76 × 106/µL, Hb 11.7 g/dL, HCT 34.7%, MCHC 256 g/L, WBC 18.15 × 103/µL, PLT 580 × 103/µL, lipase 3165 U/L, amylase 2765 U/L and the latter progressively decreased in the days after admission.

The CT-scan performed at the time of admission showed an extensive pancreatic necrosis with multiple perivisceral fluid collections. CT-scans performed 1 and 3 wk after the admission revealed the development of a walled massive fluid collection (7 cm × 20 cm × 18 cm). The CT-scan performed 6 wk after the acute episode confirmed the presence of a WOPN with increased dimensions that compressed the stomach and the first duodenal portion.

WOPN.

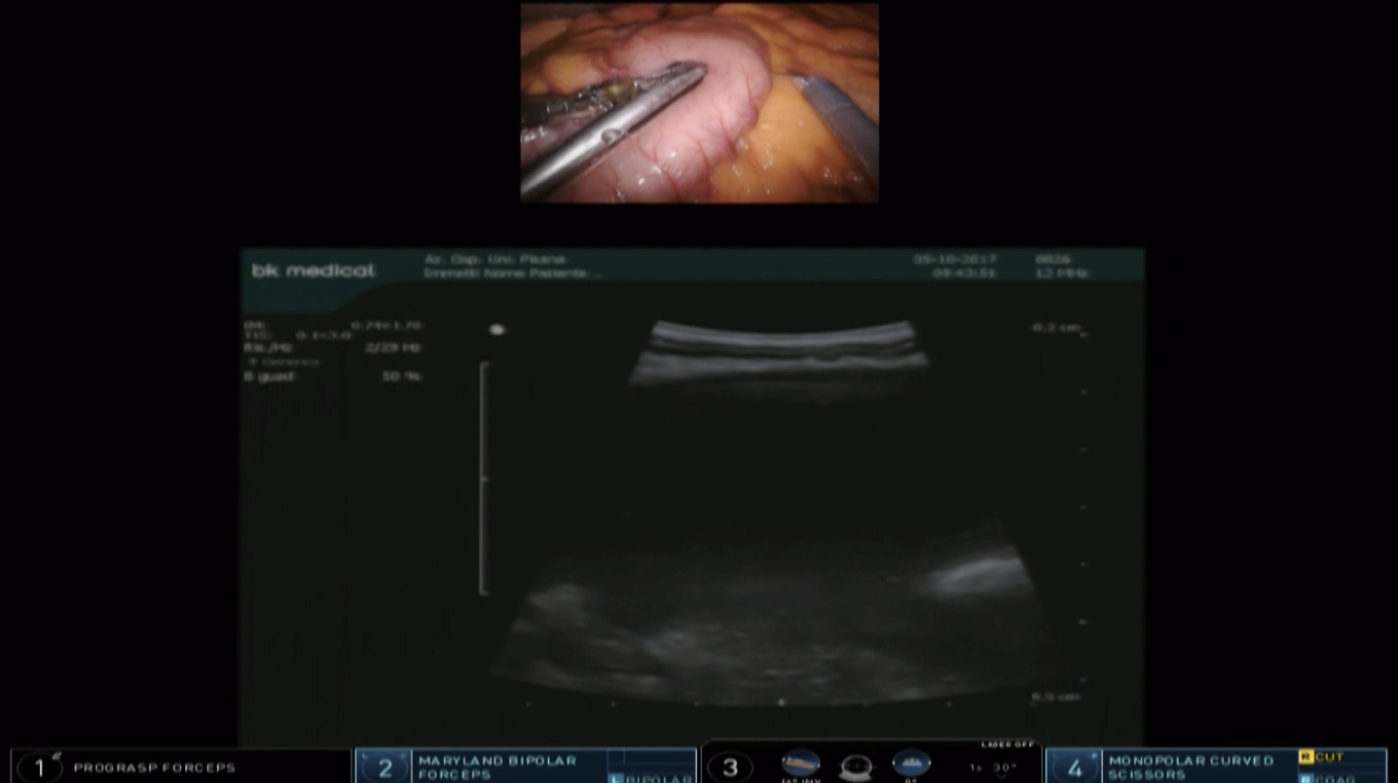

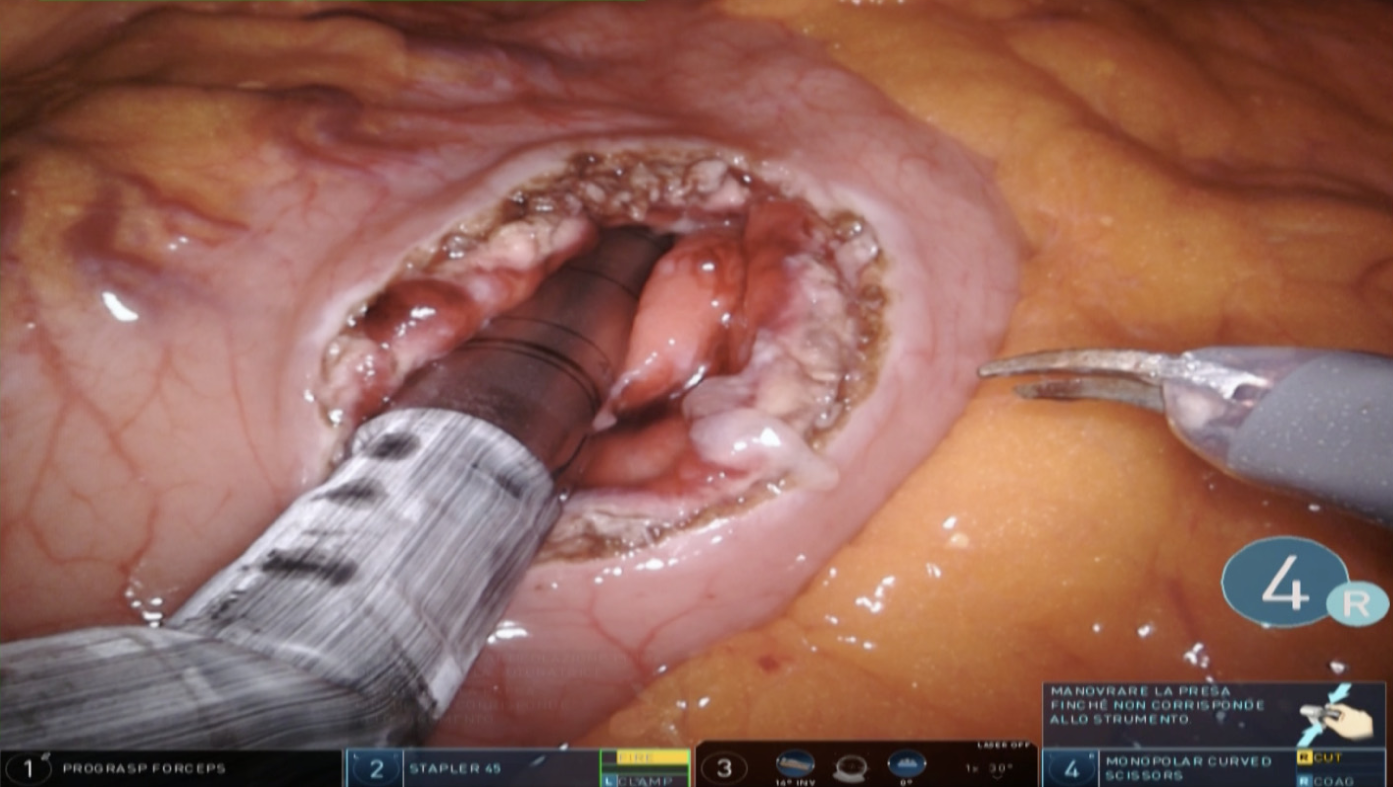

A trans-gastric drainage and debridement was successfully performed using the da Vinci Xi robotic platform. The procedure was completed in 130 min. Firstly, guided by intraoperative ultrasound (US)-scan, an anterior ideal gastrotomy was carried out (Figure 1). The intra-operative US scan was performed with a dedicated robotic probe using the TilePro™ function. This technology consents the surgeon to view 3D video of the operative field along with ultrasound exam. Then, through the gastrotomy, the best location for drainage on the posterior gastric wall was again US-guided identified. The anastomosis between the posterior gastric wall and the walled-off necrosis wall was carried out with the new EndoWrist stapler with vascular cartridge (Figure 2). Debridement and washing of the cavity through the anastomosis were performed (Figure 3). Finally, the anterior gastrotomy was closed with three layers of 3-0 V-Lock running sutures and the cholecystectomy was performed.

No intra-operative complications were recorded. The postoperative course was uneventful and a post-operative CT-scan showed the collapse of the fluid collection. Six months after discharge, the patient underwent abdominal ultrasound that confirmed the complete collapse of the abdominal fluid collections and the good mid-term result of the operation. The scheduled follow-up consists in blood tests and ultrasound examination every 6 months. CT-scan or MRI will be reserved for any variations in clinical evaluation.

The advantages of a minimally-invasive approach for the treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts and WOPN are well known[8,9]. In the last decades different minimally invasive approaches have been described in literature, including endoscopic[10], laparoscopic[11,12], SILS[13] and robotic approach[5-7]. Several cases of laparoscopic drainage of pancreatic pseudocysts by cystogastrostomy have been described since the late 90s by Smadja et al[14]. Recently, Dua et al[12] analyzed the outcomes of 46 patients underwent open and laparoscopic trans-gastric pancreatic necrosectomy, in terms of postoperative complications and mortality. Thirty-seven of these patients were treated with a laparoscopic approach and 9 with an open one. In this case series, with a median post-operative hospital stay of 6 d, 4 patients have required a percu-taneous drainage for residual fluid collection and only 6 patients (13%) had postoperative bleeding. Series of robotic approaches are lacking in literature, only some isolated case reports are present[5-7], demonstrating all the feasibility of robotic cystogastrostomy and the possibility to easier perform the debridement of the cavity.

The endoscopic approach remains a valid option for WOPN, as reported in several papers, but, in our experience, it results more indicated for the treatment of pancreatic pseudocysts, where there is not a solid component. Indeed, in the WOPN which requires extended debridement, the endoscopic approach can be very laborious and often it does not lead to the desired result. In fact, it allows to perform a small communication between the stomach and the cavity, draining predominantly the fluid component. On the other hand, in case of WOPN with significant solid component and characterized by irregular shape, the endoscopic instruments may not allow the extensive debridement that we have obtained with the described technique.

Thus, we proposed a robotic technique that presents three main key points: (1)The increased dexterity guaranteed by the robotic technology which allows to perform a safer and more radical debridement of the WOPN cavity; (2) The use of the new EndoWrist robotic stapler with the smart clamp technology, which could reduce the risk of bleeding related to the cystogastrostomy; (3) The Tile-pro™ function which gives high degree of precision in defining the best location for the gastrostomy and in detecting the presence of blood vessels.

As described in the “2012 revision of the Atlanta Classification of acute pan-creatitis”[2] the WOPN (“a mature, encapsulated acute necrotic collection with a well defined inflammatory wall”) differs from the pancreatic pseudocyst (“an encapsulated, well defined collection of fluid but no or minimal solid component”) based on the presence of a solid component and the onset timing, with a direct implication on the necessity and on the difficulty in the performing the debridement. Indeed, usually in the treatment of a pancreatic pseudocyst the only need is to let the cyst communicate with the stomach or the bowel in order to drain the liquid, thus reducing the pressure inside the pseudocyst. Instead, the necrotic material contained within the WOPN is usually denser and requires a substantial debridement. In this context, in dealing with the WOPN, the dexterity of the robotic platform can give advantages compared to laparoscopy in the execution of a more extensive and safer debridement. Indeed, the debridement of the large, irregular cavity could be compromised because of the kinematics limitations of laparoscopy, mainly due to the less degrees of freedom which limit the accessibility to the cavity in all directions and angles. The only limitation of this robotic procedure can be the lack of tactile feedback, but it could be overcome with the surgeon’s experience.

The issue of bleeding after the pseudocystogastrostomy is well known and described in literature[15-17] and it is due to the state of inflammation resulting from the pancreatitis and to the exposure of the suture to gastric acidity. Furthermore, the gastric wall is highly vascularized and the suture performed is not always completely hemostatic. The robotic stapler used in this case report thanks to the smart clamp technology, is able to note the suitable thickness of the tissues between the branches, guaranteeing to perform the suture only if the chosen charge is compatible. In this way, the controlled use of the stapler with a vascular charge, when allowed by the system, reduces the risk of post-operative bleeding, the main feared problem of this procedure. Moreover, the robotic stapler with its new EndoWrist technology can be articulated with a range of 108° and allows the operator to directly control all the steps of the suture ("positioning, grip, clamp and fire"). Finally, the new Tilepro™ function and the Xi platform, used in this case report, brought further benefits in the execution of the surgical procedure.

We used a dedicated intraoperative US probe (12-5 MHz, linear curved array, BK Medical APS, Peabody MA, United States) to identify the best location for the gastrostomy. This probe can be introduced through the assistant port and it is designed to perfectly fit the robotic instruments in order to join the maximum direct control. The TilePro™ function can superimpose ultrasound imaging on the console screen, alongside the 3D vision of the operatory field, eliminating several problems related to hand-eye coordination[18]. This specific robotic ultrasound probe, thanks to the flexible cable and the small surface, can give more flexibility than those used in pure laparoscopy, because the surgeon sitting at the console is able to manipulate the probe tip directly with the dominant hand, maintaining the perpendicular contact to the target with a high degree of precision in defining the best location for the gastrostomy and in detecting the presence of blood vessels.

The use of the Xi robotic platform is the latest addition to this clinical case. Indeed, the few previously described cases had all been performed with the Si platform[5-7]. The WOPN cavity can be anfractuous, irregular and long, increasing the risk of conflicts between the instruments. Therefore, the new da Vinci Xi, having more flexibility and reducing the risk of collision between the arms, could allow a better accessibility in the cavity during the debridement.

In selected cases of WOPN the da Vinci Surgical System can be safely used as a valid surgical treatment option in alternative to the endoscopic and to the laparoscopic approach. The enhanced surgical dexterity and the EndoWrist stapler together with the Tile-Pro multi-input display and the new Xi platform, could give some advantages in the treatment of this challenging disease.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Isik A, Paydas S, Sun S S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Connor S, Raraty MG, Howes N, Evans J, Ghaneh P, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Surgery in the treatment of acute pancreatitis--minimal access pancreatic necrosectomy. Scand J Surg. 2005;94:135-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sarr MG. 2012 revision of the Atlanta classification of acute pancreatitis. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2013;123:118-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Boškoski I, Costamagna G. Walled-off pancreatic necrosis: where are we? Ann Gastroenterol. 2014;27:93-94. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Kulkarni S, Bogart A, Buxbaum J, Matsuoka L, Selby R, Parekh D. Surgical transgastric debridement of walled off pancreatic necrosis: an option for patients with necrotizing pancreatitis. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:575-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nassour I, Ramzan Z, Kukreja S. Robotic cystogastrostomy and debridement of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. J Robot Surg. 2016;10:279-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kirks RC, Sola R, Iannitti DA, Martinie JB, Vrochides D. Robotic transgastric cystgastrostomy and pancreatic debridement in the management of pancreatic fluid collections following acute pancreatitis. J Vis Surg. 2016;2:127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cardenas A, Abrams A, Ong E, Jie T. Robotic-assisted cystogastrostomy for a patient with a pancreatic pseudocyst. J Robot Surg. 2014;8:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Redwan AA, Hamad MA, Omar MA. Pancreatic Pseudocyst Dilemma: Cumulative Multicenter Experience in Management Using Endoscopy, Laparoscopy, and Open Surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:1022-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Worhunsky DJ, Qadan M, Dua MM, Park WG, Poultsides GA, Norton JA, Visser BC. Laparoscopic transgastric necrosectomy for the management of pancreatic necrosis. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:735-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Muthusamy VR, Chandrasekhara V, Acosta RD, Bruining DH, Chathadi KV, Eloubeidi MA, Faulx AL, Fonkalsrud L, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Kothari S, Lightdale JR, Pasha SF, Saltzman JR, Shaukat A, Wang A, Yang J, Cash BD, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory pancreatic fluid collections. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gerin O, Prevot F, Dhahri A, Hakim S, Delcenserie R, Rebibo L, Regimbeau JM. Laparoscopy-assisted open cystogastrostomy and pancreatic debridement for necrotizing pancreatitis (with video). Surg Endosc. 2016;30:1235-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dua MM, Worhunsky DJ, Malhotra L, Park WG, Poultsides GA, Norton JA, Visser BC. Transgastric pancreatic necrosectomy-expedited return to prepancreatitis health. J Surg Res. 2017;219:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Singh Y, Cawich SO, Olivier L, Kuruvilla T, Mohammed F, Naraysingh V. Pancreatic pseudocyst: combined single incision laparoscopic cystogastrostomy and cholecystectomy in a resource poor setting. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;2016:pii: rjw176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Smadja C, Badawy A, Vons C, Giraud V, Franco D. Laparoscopic cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst is safe and effective. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 1999;9:401-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | George A, Panwar R, Pal S. Surgical Management of Life Threatening Bleeding after Endoscopic Cystogastrostomy. J Invest Surg. 2017;1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nielsen OS. Bleeding after pancreatic cystogastrostomy. Acta Chir Scand. 1979;145:247-249. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ikoma A, Tanaka K, Ishibe R, Ishizaki N, Taira A. Late massive hemorrhage following cystogastrostomy for pancreatic pseudocyst: report of a case. Surg Today. 1995;25:79-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guerra F, Amore Bonapasta S, Annecchiarico M, Bongiolatti S, Coratti A. Robot-integrated intraoperative ultrasound: Initial experience with hepatic malignancies. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2015;24:345-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |