Published online Jun 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1421

Peer-review started: January 3, 2019

First decision: January 30, 2019

Revised: April 22, 2019

Accepted: May 2, 2019

Article in press: May 2, 2019

Published online: June 26, 2019

Processing time: 173 Days and 10.8 Hours

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a serious health and social problem leading to a considerable decrease in the quality of life of patients. Among the risk factors associated with reflux symptoms and that decrease the quality of life are stress, overweight and an increase in body weight. The concept of health-related quality of life (HRQL) covers an expanded effect of the disease on a patient’s wellbeing and daily activities and is one of the measures of widely understood quality of life. HRQL is commonly measured using a self-administered, disease-specific questionnaires.

To determine the effect of reflux symptoms, stress and body mass index (BMI) on the quality of life.

The study included 118 patients diagnosed with reflux disease who reported to an outpatient department of gastroenterology or a specialist hospital ward for planned diagnostic tests. Assessment of the level of reflux was based on the frequency of 5 typical of GERD symptoms. HRQL was measured by a 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) and level of stress using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. Multi-variable relationships were analyzed using multiple regression.

Eleven models of analysis were performed in which the scale of the SF-36 was included as an explained variable. In all models, the same set of explanatory variables: Gender, age, reflux symptoms, stress and BMI, were included. The frequency of GERD symptoms resulted in a decrease in patients’ results according to 6 out of 8 SF-36 scales- except for mental health and vitality scales. Stress resulted in a decrease in patient function in all domains measured using the SF-36. Age resulted in a decrease in physical function and in overall assessment of self-reported state of health. An increasing BMI exerted a negative effect on physical fitness and limitations in functioning resulting from this decrease.

In GERD patients, HRQL is negatively determined by the frequency of reflux symptoms and by stress, furthermore an increasing BMI and age decreases the level of physical function.

Core tip: Gastro-esophageal reflux disease is a serious health problem leading to a decrease in the quality of life. This study determines the effect of reflux symptoms, stress and body mass index (commonly known as BMI) on the quality of life measured by a 36-item Short Form Health Survey. We demonstrate that in patients with gastro-esophageal reflux, stress decreases the quality of life to a higher degree than the frequency of reflux symptoms. Age and increasing BMI result in decreased physical function. Therefore, the patient’s stress level should be considered in the diagnosis and therapy, as well as an assessment of the progress of treatment.

- Citation: Gorczyca R, Pardak P, Pękala A, Filip R. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on the quality of life of Polish patients. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(12): 1421-1429

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i12/1421.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i12.1421

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a serious health and social problem, considering the frequency and specificity of symptoms, causing an increase in absenteeism rate, consequently creating a financial burden for health care, and above all, leading to a considerable decrease in the quality of life of patients. According to a 1999 study, reflux disease symptoms occurred every day in 7%-10%, and once a week in nearly 20% of the population in highly developed countries[1]. In 2003 in Poland, based on Carlsson’s questionnaire, reflux disease was diagnosed in more than 34% of patients aged over 15 who reported to a family physician[2]. A special problem for patients is the noxiousness of symptoms at the phase of aggravation of the disease and frequent recurrences after successful therapy. A decrease in perceived quality of life is symptomatic of GERD[3-5]. The Montreal definition describes GERD as a con-dition that develops when the reflux of stomach contents causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications. The symptoms are considered troublesome when they occur more frequently than once a week because only then they cause a decrease in the perceived quality of life[3,4].

The concept of health-related quality of life (HRQL) covers an expanded effect of the disease on a patient’s wellbeing and daily activities. To date, there is no commonly accepted definition of this concept, and the basic problem is the specification of contents of the domains of activities to which this definition refers. In practice, HRQL should refer to contents included in a given measurement instrument[5-7]. HRQL is commonly measured using a self-administered questionnaire completed by patients. Disease-specific and general questionnaires are distinguished. The first provide information concerning disorders and limitations typical of a given disease. However, this limits the possibility to compare the quality of life between patients suffering from different diseases. General (generic) questionnaires provide comparability of results, measure the respondent’s functioning within several basic spheres (domains), which are general enough in that they concern many types of diseases, and may also, within a certain scope, be reasonably measured in healthy individuals. The HRQL is one of the measures of widely understood quality of life (QOL), which covers many spheres of activity beyond the area of health and disease, but often related with it, such as interpersonal relationships in a family, social and financial problems[8]. The etiopathogenesis of GERD is multi-factorial and, in the case of individual patients, is difficult to determine unequivocally. Among the risk factors with a documented relation to reflux symptoms are, among others, stress[9-11], being overweight and obesity[11,12]. Here, stress will be understood in a narrower sense as a psychological distress, i.e. the state of strong or long-term psychological tension, connected with low mood, emotions of fear and anxiety or aggression. The relationship between stress and reflux symptoms and quality of life has been well documented. In a cross-sectional controlled population study conducted among the Norwegian population that included nearly 59000 respondents[13], the relationship was assessed between psychiatric disorders (anxiety, depression) and reflux symptoms. It was observed that anxiety and depression correlated to a 3- 4-fold increase in the risk of occurrence of reflux symptoms. In a study of reflux disease patients conducted by Nojkova et al[14], patients who had reflux symptoms and concomitant symptoms of psychological distress, showed a significantly lower quality of life and more severe reflux symptoms at the beginning of therapy compared to those without symptoms of distress. In a repeated study, after the completion of therapy with a proton pump inhibitor (rabe-prazole at a dose 20 mg/d) patients with distress continued to show a lower quality of life and higher intensity of reflux symptoms than those without distress, despite an improvement in both groups.

Although there is clear evidence for a relationship between stress and reflux symptoms, a randomized experimental study did not confirm the effect of stress on the number of reflux episodes measured using 24-h esophageal pH monitoring, despite the fact that the group subjected to stress perceived an increased intensity of symptoms in subjective evaluations[15]. While undertaking attempts to explain the relationship between experiencing reflux symptoms and stress, the researchers refer to the presence of a strong relationship between the degree of emotional tension accompanying stress and a decreased threshold of pain sensitivity. It was also observed that patients with reflux disease emphasize the inability to control pain and the randomness with which pain occurs. At the same time, they are strongly convinced that there is a relationship between their psychological condition and the intensity of the complaints experienced[16,17]. An important study that cast light on the relationship between stress and the heartburn symptoms was by Farré et al[18] examining the effect of stress on the esophageal mucosa of rats. The researchers traced changes in the esophageal mucosa using electron microscopy and concluded that strong stress may result in an increase in permeability of the esophageal mucosa. They also observed an enhanced effect between stress and exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acid, leading to increased permeability and dilatation of intracellular spaces. Additionally, obesity and being overweight are related to GERD. Epidemiolo-gical studies demonstrate that a high percentage of GERD patients are overweight or obese[19-21], and in a population of nurses, Jakobson et al[22] observed a nearly linear increase in GERD risk ratio with an increase in body mass index (BMI). One factor that correlated with GERD symptoms was lower esophageal sphincter pressure and higher intragastric pressure[20,23]. Simultaneously, an increase in body weight is negatively correlated with the level of HRQL, both in the case of somatically healthy individuals[24] and in the case of a number of diseases where, apart from the symptoms of the main disease, it is an additional factor that decreases patient HRQL[25-28].

The primary goal of the study was to determine the independent effect of reflux symptoms, stress and increasing BMI on the quality of life of patients using the SF-36 questionnaire.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Ethic Committee at the Institute of Rural Health in Lublin, Poland. Assessment of the level of reflux symptoms was based on five symptoms considered typical of GERD. The frequency of each symptom was rated by the respondent on the 5-point Likert-type scale. These were: (1) Heartburn after meals (scores from 0- never to 4- after every meal/almost after every meal); (2) Heartburn in a lying position (scores from 0- never to 4- always/almost always); (3) Waking from sleep due to heartburn (scores from 0- never to 4- every night/almost every night); (4) Regurgitation; and (5) Acid reflux (scores from 0- never to 4- always/almost always). The sum of ratings was transformed into a 0-100 range. The transformed score represents the percentage of the possible maximum score achieved. It was taken as a measure of the overall level of reflux symptoms (ORS). Reliability measured using Cronbach’s alpha homogeneity coefficient for ORS was 0.83, which suggests a good level of homogeneity of the scale.

HRQL was measured by a generic questionnaire, 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), which measures the quality of life across eight domains: (1) Physical function (PF); (2) Role limitations due to physical problems (RP); (3) Bodily pain (BP); (4) General health perceptions (GH); (5) Vitality (Vt); (6) Social function (SF); (7) Role limitations due to emotional problems (RE); and (8) Mental health perceptions (MH). In addition, single item scale Health Transition (HT) identifies perceived change in health in the last year. Based on eight basic scales, two standardized summary scales are calculated: Physical Component Summary (PCS) and Mental Component Sum-mary (MCS), which represent the physical and mental dimensions of HRQL, respectively. Calculating the results within these two dimensions, the authors of the test provided the values of factor score coefficients for eight individual scales of the test in each dimension, calculated based on a validation study in the United States. Stress levels were measured using the S. Kohen 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) as adapted by Juczyński and Ogińska-Bulik[29].

The study included 127 patients aged 19-64 diagnosed with reflux disease at various phases of treatment, who reported to a specialist outpatient department of gastroen-terology or a specialist hospital ward for planned diagnostic tests. Each patient who met the preliminary criteria of age and health status and expressed consent to participate in the study participated in a research session carried out by a psycho-logist. The study was conducted with each patient individually or in small groups of up to four patients. Ultimately, the results of 118 patients, 43 (36.4%) males and 75 (63.6%) females, were considered in the analyses.

Statistical analyses were performed using the statistical package SPSS v.22. The results of eight SF-36 scales were expressed in the form of transformed scores, i.e. the percentage of the row score to the maximum possible score in the given scale. For each of the eight scales, the value 0 was assigned to the worst and 100 to the best quality of functioning. Standardized results according to the PCS and MCS scales were converted, according to the instruction, into T-scores, with the mean 50 and standard deviation 10. Evaluations of changes in the state of health remained in raw form, i.e. according to the 5-point scale within the range of values from 1-5. Multi-variable relationships were analyzed using multiple regression. Eleven models of analysis were performed in which the subsequent scale of the SF-36 was included as an explained variable. In all models, the same set of explanatory variables (gender, age, GERD symptoms (ORS), stress (PSS-10), and BMI) was included. Analyses were performed using the backward elimination technique, the final effect of which is leaving in the model only the set of variables that have a significant effect on the explained variable.

In the examined population, females were older than males (P = 0.004): Mean age 48.4 ± 12.09 and 41.8 ± 13.21, respectively. Also, females had a lower BMI compared to males: 24.7 ± 4.51 and 26.0 ± 3.37), respectively (P = 0.034). However, the two groups did not significantly differ according to the frequency of GERD symptoms (mean value for the examined population was 45.0 ± 25.26), nor by the mean value of any of the SF-36 scales and the stress level. The age group < 50 had a lower BMI value (24.0 ± 3.78, within the normal range) than the age group > 50 years (26.4 ± 4.25, overweight, P = 0.003). These groups did not differ by the level of GERD symptoms or by stress level. In the HRQL examination, the older group showed a generally lower level of PF than the younger group (PCS: 41.7 ± 7.92 and 47.6 ± 6.33, respectively, P < 0.0001). In the case of detailed scales, significant differences were noted to the disadvantage of the older group in the scales: PF, RP, BP, GH, and also in the RE scale (Table 1).

| Variable | Sex | Age | Total, n = 118 | ||||

| M, n = 43 | F, n = 75 | Sig. | < 50 yr, n = 62 | ≥ 50 yr, n = 56 | Sig. | ||

| Age | 41.8 (13.21) | 48.4 (12.09) | 0.0044 | NA | NA | NA | 46.0 (12.86) |

| BMI | 26.0 (3.37) | 24.7 (4.51) | 0.034 | 24.0 (3.78) | 26.4 (4.25) | 0.003 | 25.2 (4.17) |

| GERD symptoms | 47.6 (26.4) | 43.6 (24.65) | 0.43 | 44.4 (23.24) | 45.7 (27.53) | 0.75 | 45.0 (25.26) |

| Stress | 19.9 (6.87) | 18.8 (3.79) | 0.65 | 18.5 (4.98) | 20.0 (5.2) | 0.13 | 19.2 (5.13) |

| PF | 79.8 (19.88) | 78.7 (17.69) | 0.54 | 87.1 (12.66) | 70.3 (19.85) | 0.000001 | 79.1 (18.44) |

| RP | 60.3 (29.06) | 61.7 (22.12) | 0.88 | 67.1 (24.59) | 54.6 (23.43) | 0.011 | 61.2 (24.76) |

| BP | 51.3 (29.45) | 42.8 (21.18) | 0.12 | 50.4 (25.41) | 40.9 (23.19) | 0.027 | 45.9 (24.74) |

| GH | 53.0 (20.46) | 52.4 (16.44) | 0.96 | 58.9 (18.51) | 45.7 (14.5) | 0.00003 | 52.6 (17.92) |

| Vt | 47.7 (17.31) | 51.1 (17.19) | 0.42 | 51.7 (16.29) | 47.7 (18.14) | 0.21 | 49.8 (17.23) |

| SF | 62.5 (23.31) | 64.0 (24.05) | 0.74 | 65.3 (24) | 61.4 (23.39) | 0.35 | 63.5 (23.69) |

| RE | 65.5 (29.07) | 68.8 (24.05) | 0.70 | 74.5 (24.97) | 60.0 (25) | 0.0022 | 67.6 (25.92) |

| MH | 56.5 (18.47) | 55.5 (17.18) | 0.49 | 57.4 (17.15) | 54.2 (18.06) | 0.39 | 55.9 (17.59) |

| HT | 3.5 (1.03) | 3.4 (0.84) | 0.62 | 3.3 (0.84) | 3.6 (0.97) | 0.12 | 3.4 (0.91) |

| PCS | 45.7 (8.69) | 44.3 (7.07) | 0.42 | 47.6 (6.33) | 41.7 (7.92) | 0.000068 | 44.8 (7.69) |

| MCS | 39.1 (11.47) | 40.4 (10.38) | 0.73 | 40.9 (10.78) | 38.9 (10.74) | 0.39 | 39.9 (10.76) |

The frequency of GERD symptoms resulted in a decrease in patients’ results according to six out of eight F-36 scales. Only in two scales, MH and Vt, the effect of GERD symptoms was insignificant. Consequently, a significant decrease in the results under the effect of symptoms was observed according to both PSC and MSC sum-mary scales.

Stress resulted in a decrease in patient function in all domains and dimensions measured using the SF-36. PF decreased as age increased, according to the results of both PF scale and PCS. Age was also the factor resulting in a decrease in overall assessment of self-reported state of health (GH). An increasing BMI exerted a negative effect on physical fitness (PF) and limitations in functioning resulting from this decrease (RP). Notably, it also caused limitations in social relations that resulted from emotional disorders (RE) (Table 2).

| Variable explained (percent of variability explained1) | Explanatory variables2 | Beta | Sig. |

| PF (41%) | Stress | -0.37 | 0.000002 |

| Age | -0.31 | 0.000097 | |

| BMI | -0.24 | 0.0022 | |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.15 | 0.045 | |

| RP (36%) | Stress | -0.47 | < 0.000001 |

| BMI | -0.26 | 0.0006 | |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.18 | 0.022 | |

| BP (29%) | Stress | -0.41 | 0.000002 |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.25 | 0.002 | |

| Sex (1 = M, 2 = F) | -0.17 | 0.028 | |

| GH (37%) | Stress | -0.43 | < 0.000001 |

| Age | -0.31 | 0.00005 | |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.17 | 0.028 | |

| Vt (45%) | Stress | -0.67 | < 0.000001 |

| SF (32%) | Stress | -0.49 | < 0.000001 |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.21 | 0.010 | |

| RE (44%) | Stress | -0.56 | < 0.000001 |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.21 | 0.004 | |

| BMI | -0.20 | 0.005 | |

| MH (59%) | Stress | -0.77 | < 0.000001 |

| PCS (30%) | Stress | -0.29 | 0.00041 |

| Age | -0.35 | 0.000017 | |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.22 | 0.0061 | |

| MCS (53%) | Stress | -0.68 | < 0.000001 |

| GERD Symptoms | -0.13 | 0.047 |

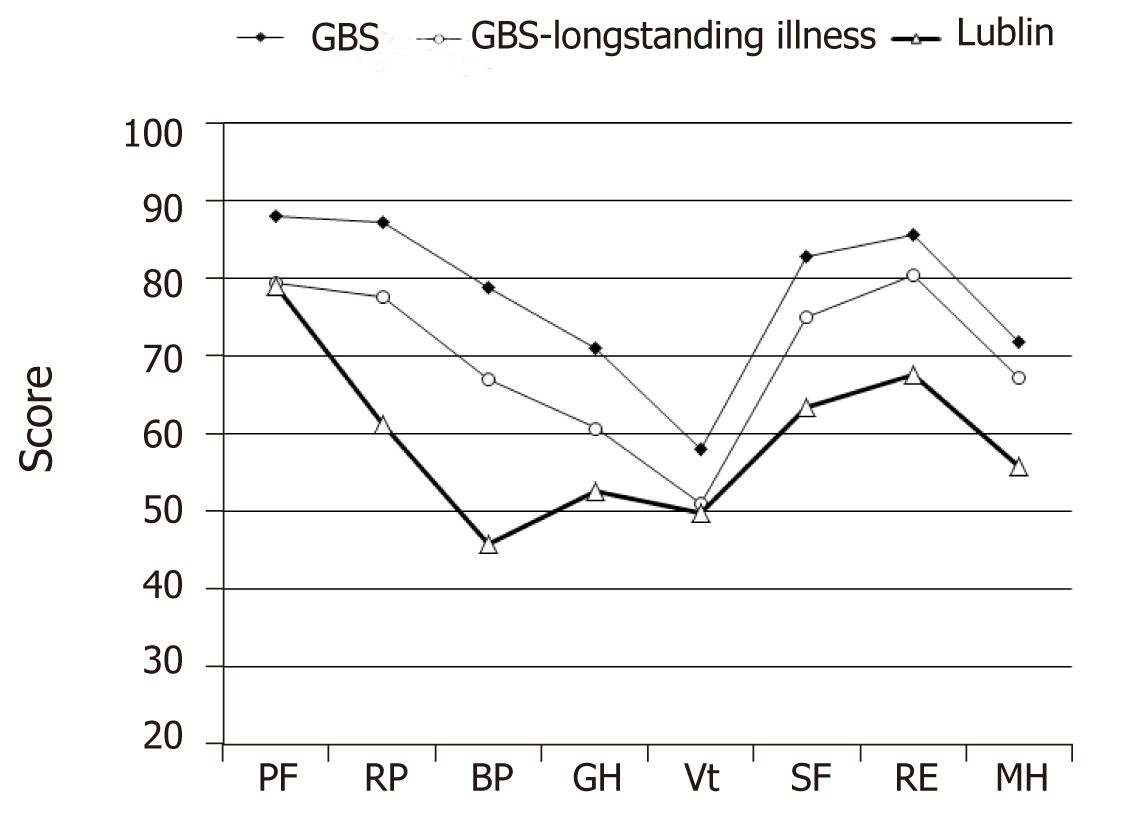

In the present study of the quality of life of patients with GERD, the control group was not considered. To compensate for this deficiency, the results of our studies using SF-36 (Lublin) were compared with the results obtained in a random sample of 8801 inhabitants of Great Britain drawn from General Practitioner Records held by the Health Authorities for Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, and Oxford-shire (GBS), and the subpopulation of chronically ill patients in this sample (GBS- longstanding illness)[30]. The sample covered 8,801 patients aged 18-64, including 43.4% of males and 55.6% of females. The groups (GBS and Lublin) were not significantly different according to age or gender (Figure 1).

Patients from Lublin showed a lower quality of life in all eight domains compared to GBS (significance of differences was analyzed using t-Student test). Compared to the GBS long-standing illness, they did not significantly differ according to the PF and Vt scales. The highest difference between the quality of the assessed domains was observed for BP. It occupied the lowest position in the Lublin population, while it was ranked 30 scores higher in the GB sample. Similarly, in American studies[31], 533 adults with a history of heartburn symptoms showed a lower quality of functioning in all eight domains compared to the general United States population.

Regression analysis demonstrated that stress and reflux complaints were two separate sources of the effect on HRQL in the general measures of physical and psychological functioning, as well as individual domains considered in SF-36. The strength of the effect of stress is especially noteworthy, as stress was the factor that decreased the HRQL in all domains and spheres (PCS, MCS). In the Vt and MH domains, stress remained the only variable that caused deterioration of the results. It is difficult to unequivocally refer to the dominant position of stress in the examined group, especially considering the fact that the sample selection for the study was not random, and it cannot be excluded that it favored more frequent occurrence among respondents distressed over the general GERD patient population[32]. The effect of stress on the domains of PF might have been partly an artifact of the method of measuring functioning in this sphere. SF-36 does not measure the actual level of PF, but the subjective self-evaluations of patients. These self-evaluations, under the effect of long-term stress accompanied by low mood and overall self-esteem, might have been subject to a disproportional decrease in actual fitness. The use of objective measures of the quality of PF would be a desired supplementation to the study. Notably, HRQL measurement using SF-36 questionnaire does not consider a several domains of functioning that are potentially important for the quality of life, such as intimate relations and sexual activity. Among patients with GERD, impaired sexual activity and avoidance of intimacy due to the disease is often observed[33]. On the other hand, SF-36 omits a widely-handled spiritual sphere- beliefs and religious activity, participation in culture- reading, interests and artistic activity.

Apart from stress and reflux complaints, increasing BMI had a limited effect on HRQL. This resulted in a decrease in the quality of life in the PF and RP domains. However, it increased the probability of occurrence of situations when emotional disorders lead to problems in relations with others and limitations in the frequency of social contacts (RE). In a survey of more than 3000 adults, Carr and Friedman[34] did not observe any deterioration in the quality of relations with others as BMI increased, except for severely obese people who experienced a higher level of tension and less support in family relations. Nevertheless, in a randomized British study, a negative effect of BMI was confirmed on the level of social functioning of females[35].

Correlation analyses do not allow for conclusions to be drawn concerning the cause-effect relationships between variables. Correlation and regression coefficients provide quantitative estimations of common variability of the analyzed variables, while determination of the directions of relationships between variables is of a non-statistic character and is based mainly on essential knowledge concerning relations in a given domain. Hence, conclusions drawn from correlation analyses do not possess the status of hypotheses, but rather the accuracy of which strengthens the scientific plausibility of the correlations revealed. Properly planned longitudinal studies may provide the ultimate solution.

The level of HRQL in patients with GERD is negatively determined by both the frequency of reflux symptoms and, to an even higher degree, by stress. An increasing BMI, irrespective of reflux symptoms, stress, and age, decreases the level of PF of GERD patients. It also leads to an increase in limitations in functioning ascribed to emotional disorders. The patient’s stress level should be considered in diagnosis and therapy, as well as an assessment of treatment progress.

Gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a common and serious health problem leading to a decrease in the quality of life of patients. The concept of health-related quality of life (HRQL) covers an expanded effect of the disease on a patient’s wellbeing and daily activities. This study evaluates the effect of GERD symptoms and factors that cause decrease in quality of life, such as stress level, age and body weight.

Since GERD leads to a considerable decrease in the quality of life, we conducted an observational study to assess the importance of its impact on the eight domains of life (physical functioning (PF), role limitations due to physical problems, bodily pain (BP), general health perceptions, vitality (Vt), social functioning, role limitations due to emotional problems and mental health perceptions) measured in a generic questionnaire. Moreover, we evaluated the importance of stress, excessive weight and age on the above-mentioned domains.

The research objective was to determine the independent effect of reflux symptoms, age, stress and increasing body mass index (BMI) on the quality of life of patients using the SF-36 questionnaire.

A total of 118 patients diagnosed with reflux disease who reported to an outpatient department of gastroenterology or a specialist hospital ward for planned diagnostic tests were recruited. Assessment of the level of reflux was based on five typical GERD symptoms, HRQL was measured by a 36-item Short Form Health Survey and level of stress using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale. Multi-variable relationships were analyzed using multiple regression. The results of our study were compared with the results obtained in a random sample of 8801 inhabitants of Great Britain drawn from General Practitioner Records held by the Health Authorities for Berkshire, Buckinghamshire, Northamptonshire, and Oxfordshire and the subpopulation of chronically ill patients in this sample.

In the examined population, the frequency of reflux symptoms resulted in a decrease in patients’ results according to six out of eight SF-36 scales-except for mental health and Vt scales. Stress resulted in a decrease in patient function in all domains measured using the SF-36. Age resulted in a decrease in PF and in an overall assessment of self-reported state of health. An increasing BMI exerted a negative effect on physical fitness and limitations in functioning resulting from this decrease. When compared to the GBS group, patients from our study showed a lower quality of life in all eight life domains. In turn, compared to the GBS-longstanding illness group, they did not significantly differ according to the PF and Vt scales. The largest difference between the quality of the assessed domains was observed for BP, which in the Lublin population occupied the lowest position, lower by 30 scores than in GB sample.

The level of HRQL in GERD patients is negatively determined by both the frequency of reflux symptoms and, to an even higher degree, by stress. An increasing BMI, irrespective of reflux symptoms, stress, and age, decreases the level of PF of GERD patients. It also leads to an increase in limitations in functioning ascribed to emotional disorders. The patient’s stress level should be considered in the diagnosis and therapy, as well as in the assessment of treatment progress.

In our study, the stress level reported by the patient turned out to be more important for HRQL than the severity of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Future studies assessing the impact of diseases on HRQL should take into account factors that are not symptoms of the disease. Moreover, in assessing the effectiveness of treatment, we should take into account the impro-vement of HRQL as well as the reduction of disease-related symptoms.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Poland

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Viswanath YKS S-Editor: Ji FF L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wang J

| 1. | Orlando RC. Reflux esophagitis. In: Yamada T, Alpers DH, Owyang C, Powell DW, Laine L (eds.). Textbook of gastroenterology. Lippincott Williams Wilkins, Philadelphia 1999; 1235–1263. |

| 2. | Reguła J. Epidemiologia choroby refluksowej w Polsce. Materiały IX Warszawskich Spotkań Gastroenterologicznych. Wydawnictwo Goldprint, Warszawa. 2003;22-25. |

| 3. | An evidence-based appraisal of reflux disease management--the Genval Workshop Report. Gut. 1999;44 Suppl 2:S1-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R; Global Consensus Group. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Revicki DA, Zodet MW, Joshua-Gotlib S, Levine D, Crawley JA. Health-related quality of life improves with treatment-related GERD symptom resolution after adjusting for baseline severity. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:73. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Chmielik A, Ciszecki J. Assessment of health-related quality of life. New Medicine. 2004;3:74-76. |

| 7. | Marcinkowska M, Malecka-Panas E. Rola czynników psychologicznych w patogenezie chorób czynnościowych przewodu pokarmowego. Przew Lek. 2007;1:56-75. |

| 8. | Kalinowska E, Tarnowski W, Banasiewicz J. Metody pomiaru jakości życia u chorych z chorobą refluksową przełyku. Gastroenterologia Polska. 2005;12:531-536. |

| 9. | Jansson C, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K. Stressful psychosocial factors and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a population-based study in Norway. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:21-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Chen M, Xiong L, Chen H, Xu A, He L, Hu P. Prevalence, risk factors and impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a population-based study in South China. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:759-767. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 1999;106:642-649. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Obesity and estrogen as risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. JAMA. 2003;290:66-72. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Jansson C, Nordenstedt H, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Johnsen R, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Severe gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms in relation to anxiety, depression and coping in a population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:683-691. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Nojkov B, Rubenstein JH, Adlis SA, Shaw MJ, Saad R, Rai J, Weinman B, Chey WD. The influence of co-morbid IBS and psychological distress on outcomes and quality of life following PPI therapy in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:473-482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Wright CE, Ebrecht M, Mitchell R, Anggiansah A, Weinman J. The effect of psychological stress on symptom severity and perception in patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:415-424. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Kamolz T, Granderath FA, Bammer T, Pasiut M, Pointner R. Psychological intervention influences the outcome of laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with stress-related symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:800-805. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Kalinowska E. Jakość życia a zaburzenia osobowości u pacjentów z chorobą refluksową przełyku leczonych chirurgicznie. Postępy Nauk Medycznych. 2007;20:430-438. |

| 18. | Farré R, De Vos R, Geboes K, Verbecke K, Vanden Berghe P, Depoortere I, Blondeau K, Tack J, Sifrim D. Critical role of stress in increased oesophageal mucosa permeability and dilated intercellular spaces. Gut. 2007;56:1191-1197. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | El-Serag H. The association between obesity and GERD: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:2307-2312. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Friedenberg FK, Xanthopoulos M, Foster GD, Richter JE. The association between gastroesophageal reflux disease and obesity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2111-2122. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Hampel H, Abraham NS, El-Serag HB. Meta-analysis: obesity and the risk for gastroesophageal reflux disease and its complications. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143:199-211. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Jacobson BC, Somers SC, Fuchs CS, Kelly CP, Camargo CA. Body-mass index and symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2340-2348. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 23. | Kouklakis G, Moschos J, Kountouras J, Mpoumponaris A, Molyvas E, Minopoulos G. Relationship between obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease as recorded by 3-hour esophageal pH monitoring. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14:117-121. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Han TS, Tijhuis MA, Lean ME, Seidell JC. Quality of life in relation to overweight and body fat distribution. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:1814-1820. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 25. | de Oliveira Ferreira N, Arthuso M, da Silva R, Pedro AO, Pinto Neto AM, Costa-Paiva L. Quality of life in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis: correlation between QUALEFFO 41 and SF-36. Maturitas. 2009;62:85-90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Gülbay BE, Acican T, Onen ZP, Yildiz OA, Baççioğlu A, Arslan F, Köse K. Health-related quality of life in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders: relationship with nocturnal parameters, daytime symptoms and comorbid diseases. Respiration. 2008;75:393-401. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 27. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD, Block G, Humphreys MH. Association among SF36 quality of life measures and nutrition, hospitalization, and mortality in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001;12:2797-2806. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Sforza E, Janssens JP, Rochat T, Ibanez V. Determinants of altered quality of life in patients with sleep-related breathing disorders. Eur Respir J. 2003;21:682-687. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Juczyński Z, Ogińska-Bulik N. Narzędzia pomiaru stresu i radzenia sobie ze stresem. Warszawa: Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych 2009; . |

| 30. | Jenkinson C, Stewart-Brown S, Petersen S, Paice C. Assessment of the SF-36 version 2 in the United Kingdom. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:46-50. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Revicki DA, Wood M, Maton PN, Sorensen S. The impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Am J Med. 1998;104:252-258. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Lee ML, Yano EM, Wang M, Simon BF, Rubenstein LV. What patient population does visit-based sampling in primary care settings represent? Med Care. 2002;40:761-770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 33. | Liker H, Hungin P, Wiklund I. Managing gastroesophageal reflux disease in primary care: the patient perspective. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:393-400. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Carr D, Friedman MA. Body Weight and the Quality of Interpersonal Relationships. Soc Psychol Q. 2006;69:127-149. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Tyrrell J, Jones SE, Beaumont R, Astley CM, Lovell R, Yaghootkar H, Tuke M, Ruth KS, Freathy RM, Hirschhorn JN, Wood AR, Murray A, Weedon MN, Frayling TM. Height, body mass index, and socioeconomic status: mendelian randomisation study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2016;352:i582. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |