Published online Jan 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.39

Peer-review started: September 21, 2018

First decision: November 2, 2018

Revised: November 19, 2018

Accepted: November 23, 2018

Article in press: November 24, 2018

Published online: January 6, 2019

Processing time: 105 Days and 22.9 Hours

No consensus has been reached in patients suspected of having inadequate bowel preparation regarding optimal salvage methods, which negatively affects the efficacy and quality of colonoscopy. The most ideal and reasonable rescue option involves early suspicion and identification of patients with inadequate preparation before sedation, additional oral ingestion of a suitable preparation formulation, and same-day colonoscopy.

To compare 0.5-L and 1-L polyethylene glycol containing ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) as additional bowel cleansing methods after a 2-L split-dose PEG + Asc regimen in patients with expected inadequate bowel preparation before colonoscopy.

Individuals with expected inadequate bowel preparation based on last stool form, such as turbid liquid, particulate liquid, or liquid with small amounts of feces, were randomized to either a 0.5-L PEG + Asc group or a 1-L PEG + Asc group. The primary endpoint was bowel preparation as assessed using the Aronchick bowel preparation scale (ABPS) and Boston bowel preparation scale (BBPS) scores. The secondary endpoints were cecal intubation time, withdrawal time, polyp detection rate (PDR), adenoma detection rate (ADR), individual compliance with additional PEG + Asc, and patient satisfaction.

Initially, 98 patients were included, but 8 were later excluded due to withdrawal of consent to participate in the study. Adequate bowel preparation (as assessed by ABPS) was observed in 80.9% (38/47) of subjects in the 0.5-L group and in 88.4% (38/43) of subjects in the 1-L group (P = 0.617). Mean total BBPS was 6.7 points in the 0.5-L group and 7.0 points in the 1-L group (P = 0.458). ADRs and PDRs were similar in the two groups, and cecal intubation and withdrawal times were not significantly different. However, mean patient satisfaction score was significantly higher in the 0.5-L group (P = 0.041).

The bowel cleaning efficacy of additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc was not inferior to that of 1-L PEG + Asc. Additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc is worthwhile when inadequate bowel preparation is expected before colonoscopy.

Core tip: The most reasonable rescue option in patients with inadequate bowel preparation is early suspicion and identification of patients with inadequate preparation before sedation, additional oral ingestion of a suitable preparation, and same-day colonoscopy. This is the first prospective randomized clinical trial to compare the effects of two additional polyethylene glycol (PEG) containing ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) doses. The study shows that the bowel cleansing efficacy of an additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc was not inferior to that of an additional 1-L PEG + Asc when administered prior to colonoscopy in patients with suspected inadequate bowel preparation. Thus, the additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen appears to be sufficient when inadequate bowel preparation is expected before initiating colonoscopy, based on considerations of bowel cleansing efficacy and patient satisfaction.

- Citation: Cho JH, Goo EJ, Kim KO, Lee SH, Jang BI, Kim TN. Efficacy of 0.5-L vs 1-L polyethylene glycol containing ascorbic acid as additional colon cleansing methods for inadequate bowel preparation as expected by last stool examination before colonoscopy. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(1): 39-48

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i1/39.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i1.39

Colonoscopy is the gold standard for colorectal screening and effectively reduces the incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer[1]. In order to achieve these goals, cecal intubation rate and adenoma detection rate are most important and both are closely related to adequate colon preparation[2,3]. Inadequate bowel preparation negatively affects the efficacy of colonoscopy as it results in longer procedure times, lower cecal intubation rates, and lower polyp detection rates[4], and it also increases patient discomfort and total scheduled costs because it shortens surveillance intervals[5].

Reported proportions of colonoscopies conducted with inadequate bowel preparation vary widely from 5% to 30% among patients referred for colonoscopy[6,7], and rates are even higher for obese patients, the elderly, men, those taking antidepressants or with a medical comorbidity, such as diabetes mellitus, stroke, or dementia, and for those with a history of insufficient colon cleaning[8-10]. In order to reduce inadequate bowel preparation, recognition of these risk factors and of poor compliance would potentially aid the selection of patients requiring a more intensive preparation regimen or more education.

In patients with inadequate bowel preparation, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guidelines recommend the use of endoscopic irrigation pumps or repeating colonoscopy on the following day with additional bowel cleansing, although evidence of the efficacy of these approaches is scant[2].

Some authors have reported on the effectiveness of colonoscopic enema as a salvage option[11,12]. However, although this technique may be a feasible salvage option for patients with inadequate bowel preparation during sedative endoscopy, further large-scale randomized studies are needed to clarify its usefulness and safety.

Early identification of patients with inadequate bowel preparation before colonoscopy might allow salvage options to be implemented to improve quality of bowel preparation before sedation. Fatima et al[13] reported brown liquid or solid last rectal effluent was associated with a high (54%) risk of fair or poor preparation, and suggested that in this event, additional bowel cleansing using large volume enemas or an oral preparation formulation could be considered.

No consensus has been reached on optimal salvage methods for inadequate bowel preparation. Many studies have compared bowel cleansing methods or sought to identify the risk factors of inadequate bowel preparation, however, few or no studies have examined the efficacy of additional oral preparations when inadequate bowel preparation is suspected.

In this study, we aimed to compare the efficacy of 0.5-L and 1-L polyethylene glycol (PEG) containing ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) as additional bowel cleansing methods for inadequate bowel preparation as expected by last stool examination before colonoscopy.

This prospective, investigator–blinded, randomized study was conducted at the endoscopy unit of Yeungnam University Hospital between July 2016 and May 2017. The study complied with the Helsinki Declaration and the protocol and informed consent form used were approved beforehand by our institutional review board (IRB No. 2016-03-019).

Patients eligible for inclusion were aged between 18 and 85 years who underwent screening colonoscopy at the health promotion center of Yeungnam University Hospital. The initial bowel preparation method used for colonoscopy was a 2-L split-dose PEG + Asc regimen. Exclusion criteria were: (1) clear liquid or semi-solid stool as last rectal effluent; (2) history of colorectal surgery; (2) known or expected bowel obstruction or perforation; (3) inflammatory bowel disease; (4) American Society of Anesthesiologists Classes III and IV; (5) pregnancy or lactation; (6) a body weight exceeding 100 kg; (7) intolerance of the preparation agent; and (8) inability to provide informed consent.

Patients were presented with prepared representative photographs of stool forms and asked to indicate the appearance of last rectal effluent on arrival at the endoscopy room. Patients indicating a turbid liquid, particulate liquid, or liquid containing small amounts of feces were randomized 1:1 (using a computer-generated code) to either a 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen (0.5-L group) or a 1-L PEG + Asc regimen (1-L group). Colonoscopists, nurses, and investigators who participated in the study were all unaware of group allocations before, during, and after procedures. Written informed consent was obtained from all the 90 study subjects.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were collected at enrollment, and included details of medical comorbidities and histories of abdominal or pelvic surgery. The following information was also collected: dietary compliance, number of defecations, time between preparation and colonoscopy, compliance with additional PEG + Asc, adverse effects of PEG + Asc, and patient satisfaction (satisfaction scores were obtained using a 10-point visual analog scale).

All patients signed a detailed informed consent form before colonoscopy. Colonoscopic examinations were performed by one of five fully skilled endoscopists who conducted more than 400 colonoscopies per year. The Aronchick Bowel Preparation Scale (ABPS)[14] and Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS)[15] scores were awarded during the procedure by consensus between two endoscopists unaware of group allocations. ABPS and BBPS scores were included in colonoscopy reports with findings. All endoscopists participating in this study had used these scales for several months before study commencement, and had watched educational videos on the use of the BBPS classification system.

The main objective of this study was to compare bowel preparation rates in the 0.5-L and 1-L groups. Bowel preparation adequacy was scored by the endoscopist immediately after endoscope withdrawal using the ABPS and the BBPS. Detailed descriptions of these scoring systems are provided in Tables 1 and 2.

| Grade | Point(s) | Description |

| Excellent | 1 | Small amount of clear liquid with clear mucosa seen; more than 95% of mucosa seen |

| Good | 2 | Small amount of turbid fluid without feces not interfering with examination; more than 90% of mucosa seen |

| Fair | 3 | Moderate amount of stool that can be cleared with suctioning permitting adequate evaluation of entire colonic mucosa; more than 90% of mucosa seen |

| Poor | 4 | Inadequate but examination completed; enough feces or turbid fluid to prevent a reliable examination; less than 90% of mucosa seen |

| Inadequate | 5 | Re-preparation required; large amount of fecal residue precludes a complete examination |

| Point(s) | Description |

| 0 | Unprepared colon segment with stool that cannot be cleared |

| 1 | Portion of mucosa in segment seen after cleaning, but other areas not seen because of retained material |

| 2 | Minor residual material after cleaning, but mucosa of segment generally well seen |

| 3 | Entire mucosa of segment well seen after cleaning |

The secondary study endpoints were cecal intubation rate and time, withdrawal time, polyp detection rate (PDR), adenoma detection rate (ADR), compliance with the additional PEG + Asc regimen, and patient satisfaction. Cecal intubation was verified by identification of the appendix orifice and ileocecal valve on endoscopic images. Withdrawal time from the cecum was measured using a stop watch after deducting times taken for biopsies and polypectomy. PDR was defined as the percentage of patients with at least one polyp and ADR was defined as the percentage of patients with at least one adenoma.

Sample size was calculated by assuming a 25% difference in the rate of adequate bowel preparation. Based on the assumption that 65% of the patients in the 0.5-L group and 90% in the 1-L group would achieve adequate bowel preparation and an anticipated dropout rate of 10%, we calculated that at least 90 participants were needed to reach a power of 80% (type I error, 5%).

Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using the Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test. Categorical variables are expressed as absolute numbers and proportions. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The analyses were conducted using SPSS version 20.0 (SPSS; Chicago, IL, United States) and statistical significance was accepted for P-values < 0.05.

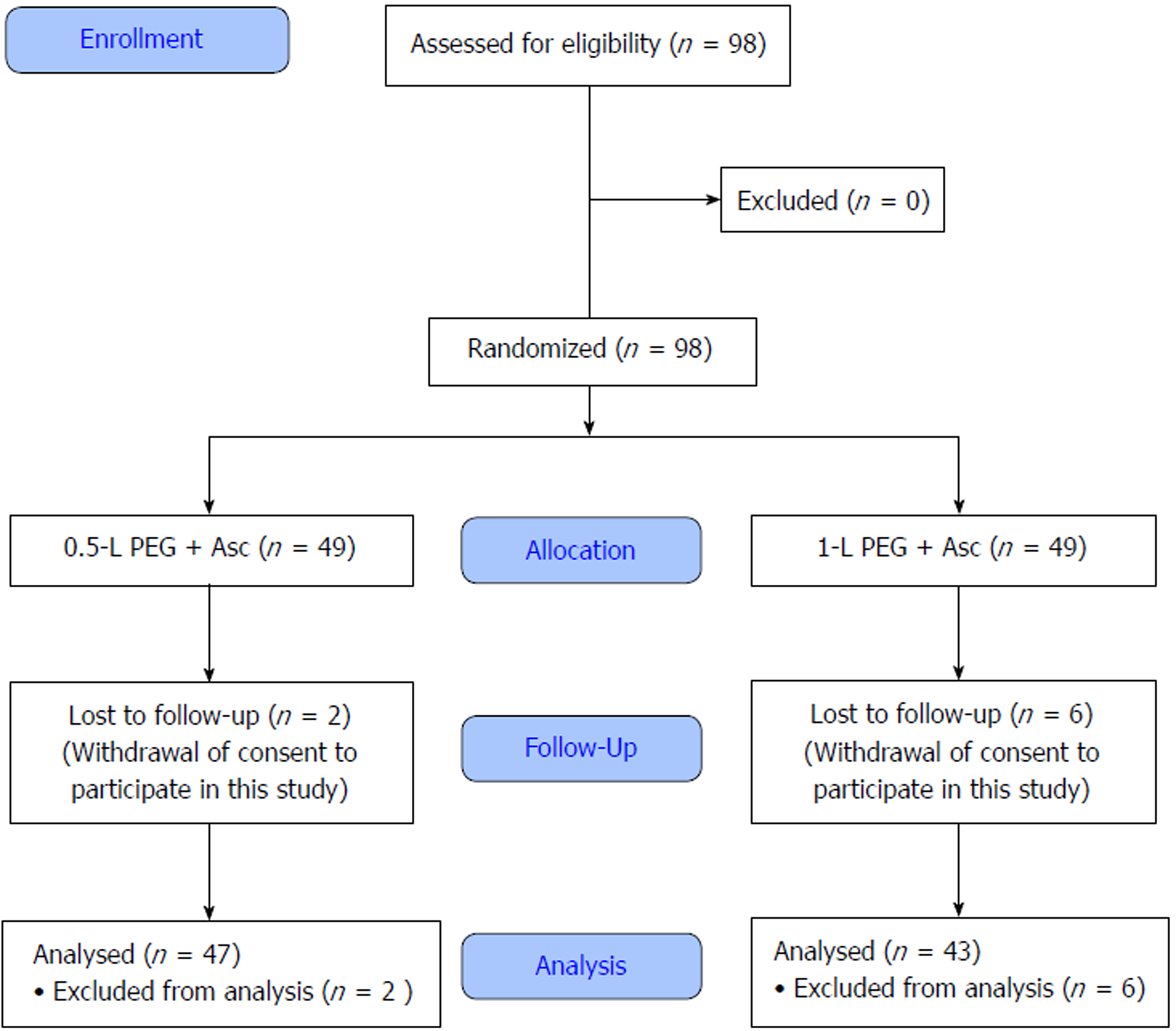

From July 2016 to May 2017, 98 patients who visited the health promotion center at our hospital for screening colonoscopy were expected to have inadequate bowel preparation based on last rectal effluents of turbid liquid, particulate liquid, or liquid with small amounts of feces. Of these patients, 8 (2 in the 0.5-L group and 6 in the 1-L group) were excluded after initial inclusion due to withdrawal of consent to participate in the study (Figure 1). Finally, 47 patients in the 0.5-L group and 43 patients in the 1-L group were analyzed.

Mean age of the 90 study subjects was 48.0 ± 11.1 years (range, 22–72) and 61 patients (67.8%) were male (Table 3). Age, sex, and BMI were not significantly different between the 0.5-L and 1-L groups (P = 0.126, P = 0.287, and P = 0.150, respectively). Furthermore, no intergroup differences were observed for medical comorbidity, which included a history of abdominal or pelvic surgery, for dietary compliance before colonoscopy, or for last rectal effluent characteristics (P = 0.412).

| 0.5-L Group (n = 47) | 1-L Group (n = 43) | Total (n = 90) | P value | ||

| Age, years | |||||

| mean ± SD | 49.7 ± 11.2 | 46.2 ± 10.8 | 48.0 ± 11.1 | 0.126 | |

| Median (range) | 51 (29-72) | 48 (22-64) | 49 (22-72) | ||

| Sex (male) | 29 (61.7) | 32 (74.4) | 61 (67.8) | 0.287 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.2 ± 3.1 | 25.0 ± 3.4 | 24.6 ± 3.4 | 0.150 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Diabetes | 7 (14.9) | 4 (9.3) | 11 (12.2) | 0.626 | |

| Hypertension | 6 (12.8) | 6 (14.0) | 12 (13.3) | 1.000 | |

| Abdominal surgery | 10 (21.3) | 9 (20.9) | 19 (21.1) | 1.000 | |

| Dietary compliance | 23 (48.9) | 18 (41.8) | 41 (45.5) | 0.369 | |

| Characteristic of last rectal effluent | 0.412 | ||||

| Turbid liquid | 34 (72.3) | 27 (62.8) | 61 (67.8) | ||

| Particulate liquid | 13 (27.7) | 15 (34.9) | 28 (31.1) | ||

| Liquid with small amounts of feces | 0 (0) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Number of defecations | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 3.5 ± 1.2 | 0.000 | |

| Interval between preparation and colonoscopy | 86.3 ± 32.9 | 78.6 ± 27.1 | 82.6 ± 30.3 | 0.232 | |

All study subjects took additional PEG + Asc. The number of defecations after additional bowel cleansing was significantly higher in the 1-L group (3.0 ± 0.8 vs 3.9 ± 1.3, P < 0.001). No significant intergroup difference was observed between mean times from the completion of taking additional PEG to colonoscopy (86.3 ± 32.9 min vs 78.6 ± 27.1 min for the 0.5-L and 1-L groups, respectively; P = 0.232).

Bowel preparation quality in the two groups is summarized in Table 4. The adequate bowel preparation as assessed by ABPS was achieved in 80.9% (38/47) of patients in the 0.5-L group [Excellent, 7 (14.9%); Good, 31 (66.0%)] and in 88.4% (38/43) of patients in the 1-L group [Excellent, 7 (16.3%); Good, 31 (72.1%)], and no significant intergroup difference was found between adequate bowel preparation rates (P = 0.617). Mean total BBPS scores in the 0.5-L and 1.0-L groups were 6.7 ± 1.5 and 7.0 ± 1.7 points, which were also not significantly different (P = 0.342). Furthermore, the numbers of patients in the 0.5-L and 1.0-L groups with a BBPS score of > 8 were not significantly different [13/47 (27.7%) vs 16/43 (37.2%), P = 0.458].

| 0.5-L Group (n = 47) | 1-L Group (n = 43) | Total (n = 90) | P value | ||

| ABPS | 0.617 | ||||

| Excellent | 7 (14.9) | 7 (16.3) | 14 (15.6) | ||

| Good | 31 (66.0) | 31 (72.1) | 62 (68.9) | ||

| Fair | 9 (19.1) | 5 (11.6) | 14 (15.6) | ||

| BBPS | |||||

| Mean | 6.7 ± 1.5 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 1.6 | 0.342 | |

| BBPS ≥ 8 | 13 (27.7) | 16 (37.2) | 29 (32.2) | 0.458 | |

The results of colonoscopy are summarized in Table 5. Cecal intubation failed because of poor bowel preparation in one patient in the 1-L group with a last rectal effluent characteristic of liquid with small amounts of feces. Successful cecal intubation rates were similar in the two groups (P = 0.964). Furthermore, cecal intubation and withdrawal times in the 0.5-L and 1.0-L groups were not significantly different (3.3 ± 1.7 vs 3.6 ± 2.3, P = 0.507; 8.3 ± 2.3 vs 7.9 ± 2.5, P = 0.432, respectively), and PDRs and ADRs were similar (17/47 (36.2%) vs 19/43 (44.2%), P = 0.575; 13/47 (27.7%) vs 16/43 (37.2%), P = 0.870, respectively).

| 0.5-L Group (n = 47) | 1-L Group (n = 43) | Total (n = 90) | P value | |

| Cecal intubation | 47 (100.0) | 42 (97.7) | 89 (98.9) | 0.964 |

| Cecal intubation time (min) | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.6 ± 2.3 | 3.4 ± 2.0 | 0.507 |

| Withdrawal time (min) | 8.3 ± 2.3 | 7.9 ± 2.5 | 8.1 ± 2.4 | 0.432 |

| PDR | 17 (36.2) | 19 (44.2) | 36 (40.0) | 0.575 |

| ADR | 13 (27.7) | 16 (37.2) | 29 (32.2) | 0.870 |

| Advanced ADR | 3 (6.4) | 4 (9.3) | 7 (7.8) | 1.000 |

The percentages of patients who completed taking additional PEG + Asc were similar in the 0.5-L and 1.0-L groups (44/47 (93.6%) vs 37/43 (86.0%), P = 0.399), and the incidences of adverse effects associated with additional PEG, such as abdominal discomfort, nausea, or vomiting, were also similar (P = 0.907, P = 0.330, and P = 0.634, respectively) (Table 6). However, mean patient satisfaction score was significantly higher in the 0.5-L group (6.7 ± 1.8 vs 5.9 ± 1.9, P = 0.041).

| 0.5-L Group (n = 47) | 1-L Group (n = 43) | Total (n = 90) | P value | ||

| Compliance to additional PEG + Asc | 44 (93.6) | 37 (86.0) | 81 (90.0) | 0.399 | |

| Adverse effects of PEG | 31 (66.0) | 23 (53.5) | 54 (60.0) | 0.322 | |

| Abdominal discomfort | 29 (61.7) | 28 (65.1) | 57 (63.3) | 0.907 | |

| Nausea | 33 (70.2) | 25 (58.1) | 58 (64.4) | 0.33 | |

| Vomiting | 5 (10.6) | 7 (16.3) | 12 (13.3) | 0.634 | |

| Patient’s satisfaction | 6.7 ± 1.8 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 6.3 ± 1.9 | 0.041 | |

Studies conducted to identify the risk factors of inadequate bowel preparation[16-18] have shown that it is associated with a history of insufficient colon cleaning, use of antidepressants, obesity, old age, male gender, and the presence of a medical comorbidity, such as diabetes mellitus, stroke, or dementia[8-10]. Furthermore, poor compliance with bowel cleansing procedures, inadequate administration of bowel preparation agent, and prolonged pre-procedure waiting times have also been shown to result in poor bowel preparation[9,10]. However, a model incorporating the above-mentioned risk factors achieved a prediction rate of just 60%[9]. Therefore, in patients undergoing first colonoscopy, the ESGE guidelines do not recommend the use of this model for identifying those at high risk of poor bowel preparation and modifying preparatory procedures[2].

Two studies have been conducted on the usefulness of intensive bowel cleansing strategies in patients with a history of poor bowel preparation[19,20]. Ibáñez et al[19] reported that an intensive regimen consisting of a low-fiber diet for 3 days, bisacodyl (10 mg) during the evening prior to colonoscopy, and a split dose of PEG can achieve good colon preparation and improve polyp and adenoma detection rates in most patients with a poor bowel preparation history. In a randomized, controlled, phase IV, single-blind study performed to compare two intensive bowel cleansing regimens in patients with inadequate bowel preparation at previous colonoscopy, a 3-day low-residue diet, oral bisacodyl before colonoscopy, and colon cleansing using 4-L split-dose PEG was superior to 2-L split-dose PEG + Asc[20].

The ESGE guidelines recommend the use of endoscopic irrigation pumps or repeat colonoscopy on the following day (after further colon cleansing) in patients with insufficient bowel preparation, but these approaches lack an evidential basis[2]. After starting colonoscopy, a preliminary assessment should be made in the rectosigmoid colon, and if inadequate preparation is deemed to interfere with the detection of polyps > 5 mm, the following salvage options can be considered: colonoscopic enema and further oral ingestion of a preparation formulation followed by same-day or next day colonoscopy[21].

The usefulness of colonoscopic enema as a salvage method at colonoscopy has been previously described[11,12]. Horiuchi et al[11] used this technique in 26 patients with inadequate preparation assessed in the rectosigmoid region. PEG solution (500 mL) was infused into the colon at the level of the hepatic flexure through an accessory channel of colonoscope. The authors reported successful subsequent colonoscopy without complication in 96% (25/26) of patients. In another study, colonoscopic enema with sodium phosphate followed by bisacodyl (37 mL/10 mg) or two tablets of bisacodyl was instilled into the right colons of patients with insufficient bowel preparation, and successful colon preparations were achieved in all cases[12].

Rescue colonoscopic enemas can avoid the necessity for colonoscopy delay, expenses of rescheduling, and anxiety about the possibility of a colonic pathology. However, in order to perform these approaches, there must be several requirements[12]. The first is an expert colonoscopist. The ability to reach over the hepatic flexure in a suboptimally prepared colon may be difficult and require skill and experience. Thus, an experienced colonoscopist that is able to insert a colonoscope completely in poorly prepared patients is required for colonoscopic enema. The second requirement is bathroom within or next to the endoscopy room. The third is that sedation must be performed with a short-acting agent like propofol, which permits patients to solve their defecation needs with minimal or no assistance. Prolonged recovery from benzodiazepine and/or opioid (e.g., meperidine or pethidine) sedation often prevents patients solving their defecation needs safely and comfortably. Fourth, more nursing resources are needed to ensure that patients are under care, observation, and are being monitored until they achieve recovery from propofol anesthesia, when a nurse’s aide is required until patients demonstrate the ability to function independently. In Korea, the low cost of national health insurance and the healthcare environment require the examination of large numbers of patients, which means that it is difficult to meet these conditions in actual clinical situations.

The most ideal and reasonable rescue option in patients with inadequate bowel preparation is early suspicion and identification of patients with inadequate preparation before sedation, additional oral ingestion of preparation formulation, and same-day colonoscopy. Additional bowel cleansing before proceeding with colonoscopy might reduce endoscopy team work burdens and save time as compared with rescue options such as colonoscopic enema or further oral ingestion of PEG after confirmation of inadequate preparation by colonoscopy. Therefore, it is desirable to induce adequate bowel preparation, if possible, before colonoscopy, and colonoscopic enema or further oral ingestion of PEG after colonoscopy should be considered as a secondary salvage option.

According to the ESGE guidelines, repeated colonoscopy on the following day (after further colon cleansing) is recommended in patients with insufficient bowel preparation, but we suggest that for reasons of patient inconvenience and increased costs, same day examinations should be considered. No consensus has been reached regarding optimal salvage methods for inadequate preparation, and few or no studies have investigated the efficacy of additional oral ingestion of preparation formulas when inadequate bowel preparation is expected.

In a previous report[13], patients that reported brown liquid or brown solid in their last rectal effluent were found to be at substantial risk (54%) of fair or poor preparation as judged by an endoscopist. Such patients may benefit from additional laxative or enema administration before proceeding with colonoscopy. The present study was conducted on patients with last rectal effluent of turbid liquid, particulate liquid, or liquid with small amounts of feces before colonoscopy, and these patients were randomized to a 0.5-L or a 1-L PEG + Asc group. Of the 90 study subjects with expected inadequate bowel preparation, 76 (84.4%) showed excellent or good preparation as assessed by BBPS during colonoscopy. Although this result is no better than that previously reported for colonoscopic enema, we believe it to be acceptable given the above-mentioned difficulties associated with meeting the requirements of colonoscopic enema.

Some limitations of the present study warrant consideration. First, in order to suspect poor preparation before colonoscopy, we used patients’ descriptions of last rectal effluent, although they were aided by representative photographs. Therefore, unlike the above-mentioned study on colonoscopic enema, it was not possible to assess improvements in bowel preparation objectively. Second, patient satisfaction scores were assessed using a 10-point visual analog scale. This is only a subjective and semiquantitative grading system. Third, the number of patients included was relatively small, and thus, it was difficult to compare the two study groups with respect to some variables and perform further analysis. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first prospective randomized trial to compare the effects of two additional PEG + Asc doses in patients suspected to be poorly prepared for colonoscopy.

In conclusion, the efficacy of the additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen was not inferior to the additional 1-L PEG + Asc regimen as a salvage option for inadequate bowel preparation as expected by last stool before colonoscopy. In addition, patient satisfaction was significantly higher in the 0.5-L group than in the 1-L group. We recommend the additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen be considered when inadequate bowel preparation is expected before colonoscopy.

Inadequate bowel preparation negatively affects the efficacy and quality of colonoscopy. However, no consensus has been reached regarding optimal salvage methods in patients suspected of having inadequate bowel preparation. Some reports have been issued on the effectiveness of colonoscopic enema in this context, but the most ideal and reasonable rescue option involves early suspicion and identification of patients with inadequate preparation before sedation, additional oral ingestion of a suitable preparation formulation, and same-day colonoscopy.

Many studies have compared the efficacy of bowel cleansing methods or sought to identify the risk factors of inadequate bowel preparation. However, few have examined the efficacy of additional oral preparations when inadequate bowel preparation is suspected. Therefore, we compared the bowel cleansing efficacy of 0.5-L polyethylene glycol containing ascorbic acid (PEG + Asc) and 1-L PEG + Asc as rescue options before colonoscopy.

The objective of this investigation was to compare the efficacy of 0.5-L and 1-L PEG + Asc as additional bowel cleansing methods for inadequate bowel preparation as expected by last stool examination before colonoscopy.

Over a 10-mo period, 90 patients expected to have inadequate bowel preparation before screening colonoscopy were included in this prospective, investigator–blinded, randomized study. Patients with last rectal effluents described as turbid liquid, particulate liquid, or liquid with small amounts of feces were equally randomized to a 0.5-L PEG + Asc group or a 1-L PEG + Asc group.

No significant intergroup differences were found between the two groups with respect to adequate bowel preparation (as assessed by Aronchick bowel preparation scale and Boston bowel preparation scale). Polyp detection rates and adenoma detection rates were similar in the two groups, and cecal intubation and withdrawal times were not significantly different. However, mean patient satisfaction score was significantly higher in the 0.5-L group.

Of the study subjects, 84.4% showed excellent or good preparation as assessed by BBPS during colonoscopy. The efficacy of the additional 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen was not inferior to the additional 1-L PEG + Asc regimen as a salvage option for inadequate bowel preparation as expected by last stool before colonoscopy. Furthermore, patient satisfaction was significantly higher in the 0.5-L group. Thus, the 0.5-L PEG + Asc regimen appears to be sufficient when inadequate bowel preparation is expected before initiating colonoscopy, based on considerations of bowel cleansing efficacy and patient satisfaction.

This study is the first prospective randomized trial to compare the effects of two additional PEG + Asc doses in patients suspected to be poorly prepared for colonoscopy. If less uncomfortable and low-volume oral preparations are developed in the near future, research on oral rescue preparation for inadequate bowel preparation before colonoscopy will become more active.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fiorentini G S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Bian YN

| 1. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF, Stewart ET, Waye JD. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2283] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Rembacken B, Saunders B, Benamouzig R, Holme O, Green S, Kuiper T, Marmo R, Omar M, Petruzziello L, Spada C, Zullo A, Dumonceau JM; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 25.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Johnson DA, Barkun AN, Cohen LB, Dominitz JA, Kaltenbach T, Martel M, Robertson DJ, Richard Boland C, Giardello FM, Lieberman DA, Levin TR, Rex DK; US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Optimizing adequacy of bowel cleansing for colonoscopy: recommendations from the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1528-1545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 642] [Cited by in RCA: 698] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: oral bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:373-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ben-Horin S, Bar-Meir S, Avidan B. The outcome of a second preparation for colonoscopy after preparation failure in the first procedure. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:626-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wexner SD, Beck DE, Baron TH, Fanelli RD, Hyman N, Shen B, Wasco KE; American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons. A consensus document on bowel preparation before colonoscopy: prepared by a task force from the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS), the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:894-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hassan C, Fuccio L, Bruno M, Pagano N, Spada C, Carrara S, Giordanino C, Rondonotti E, Curcio G, Dulbecco P, Fabbri C, Della Casa D, Maiero S, Simone A, Iacopini F, Feliciangeli G, Manes G, Rinaldi A, Zullo A, Rogai F, Repici A. A predictive model identifies patients most likely to have inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:501-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nguyen DL, Wieland M. Risk factors predictive of poor quality preparation during average risk colonoscopy screening: the importance of health literacy. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:369-372. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Horiuchi A, Nakayama Y, Kajiyama M, Kato N, Kamijima T, Ichise Y, Tanaka N. Colonoscopic enema as rescue for inadequate bowel preparation before colonoscopy: a prospective, observational study. Colorectal Dis. 2012;14:e735-e739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sohn N, Weinstein MA. Management of the poorly prepared colonoscopy patient: colonoscopic colon enemas as a preparation for colonoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:462-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fatima H, Johnson CS, Rex DK. Patients’ description of rectal effluent and quality of bowel preparation at colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1244-1252.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aronchick CA, Lipshutz WH, Wright SH, Dufrayne F, Bergman G. A novel tableted purgative for colonoscopic preparation: efficacy and safety comparisons with Colyte and Fleet Phospho-Soda. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:346-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 318] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rex DK, Bond JH, Winawer S, Levin TR, Burt RW, Johnson DA, Kirk LM, Litlin S, Lieberman DA, Waye JD, Church J, Marshall JB, Riddell RH; U. Quality in the technical performance of colonoscopy and the continuous quality improvement process for colonoscopy: recommendations of the U.S. Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1296-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 691] [Cited by in RCA: 722] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rex DK, Petrini JL, Baron TH, Chak A, Cohen J, Deal SE, Hoffman B, Jacobson BC, Mergener K, Petersen BT, Safdi MA, Faigel DO, Pike IM; ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:873-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 29.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chokshi RV, Hovis CE, Hollander T, Early DS, Wang JS. Prevalence of missed adenomas in patients with inadequate bowel preparation on screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1197-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ibáñez M, Parra-Blanco A, Zaballa P, Jiménez A, Fernández-Velázquez R, Fernández-Sordo JO, González-Bernardo O, Rodrigo L. Usefulness of an intensive bowel cleansing strategy for repeat colonoscopy after preparation failure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:1578-1584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gimeno-García AZ, Hernandez G, Aldea A, Nicolás-Pérez D, Jiménez A, Carrillo M, Felipe V, Alarcón-Fernández O, Hernandez-Guerra M, Romero R, Alonso I, Gonzalez Y, Adrian Z, Moreno M, Ramos L, Quintero E. Comparison of Two Intensive Bowel Cleansing Regimens in Patients With Previous Poor Bowel Preparation: A Randomized Controlled Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:951-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee J. Bowel preparation formulations and salvage options for inadequate preparation. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2016;68:61–63. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |