Published online Aug 16, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.219

Peer-review started: July 11, 2018

First decision: July 11, 2018

Revised: July 24, 2018

Accepted: August 1, 2018

Article in press: August 1, 2018

Published online: August 16, 2018

Processing time: 50 Days and 7.7 Hours

Leiomyosarcoma of an artery is very rare, and cases with hepatic metastasis are even rarer. We describe a case of a 70-year-old man who after follow up due to rectal cancer, presented with an intra-abdominal hypervascular mass and a hepatic mass. After surgical resection, it was diagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma of the right gastroepiploic artery with hepatic metastasis. Multiple metastases had recurred at the liver. He has survived more than 53 mo through multimodal treatments (three surgical resections, radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, chemotherapies, and targeted therapy). Multimodal treatments, including active surgical resection, may be helpful in the treatment of aggressive diseases such as arterial leiomyosarcoma with metastasis.

Core tip: An arterial leiomyosarcoma (aLMS) is a very rare and aggressive disease. The prognosis is also very poor. A 70-year-old man presented with an intra-abdominal aLMS with hepatic metastasis. He was treated with multimodal treatments that consisted of three surgeries, radiofrequency ablation, transarterial chemoembolization, and targeted therapy. He has survived for 53 mo after these treatments. Multimodal treatments could be helpful treating this kind of disease.

- Citation: Seo HI, Kim DI, Chung Y, Choi CI, Kim M, Yun S, Kim S, Park DY. Multimodal treatments of right gastroepiploic arterial leiomyosarcoma with hepatic metastasis: A case report and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(8): 219-223

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i8/219.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.219

The leiomyosarcoma (LMS) is very rare malignant tumor. They usually originate in the smooth muscle of the soft tissues and uterus[1]. About 2% of LMS cases occur in the smooth muscle of the vessel wall and 60% occur in the inferior vena cava. The occurrence of LMS involving the veins is about five times higher than that of the arteries[1]. The most common site of arterial LMS (aLMS) is the peripheral artery, and the intra-abdominal artery is a rare location for aLMS to occur[1]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first presentation of intra-abdominal aLMS with distant single liver metastasis. We report the clinical course of aLMS that originated from the right gastroepiploic artery with hepatic metastasis during multimodal treatments [three surgical resections, radiofrequency ablation (RFA), transarterial chemoembolization (TACE), chemotherapy, and targeted therapy] and review the literature regarding aLMS.

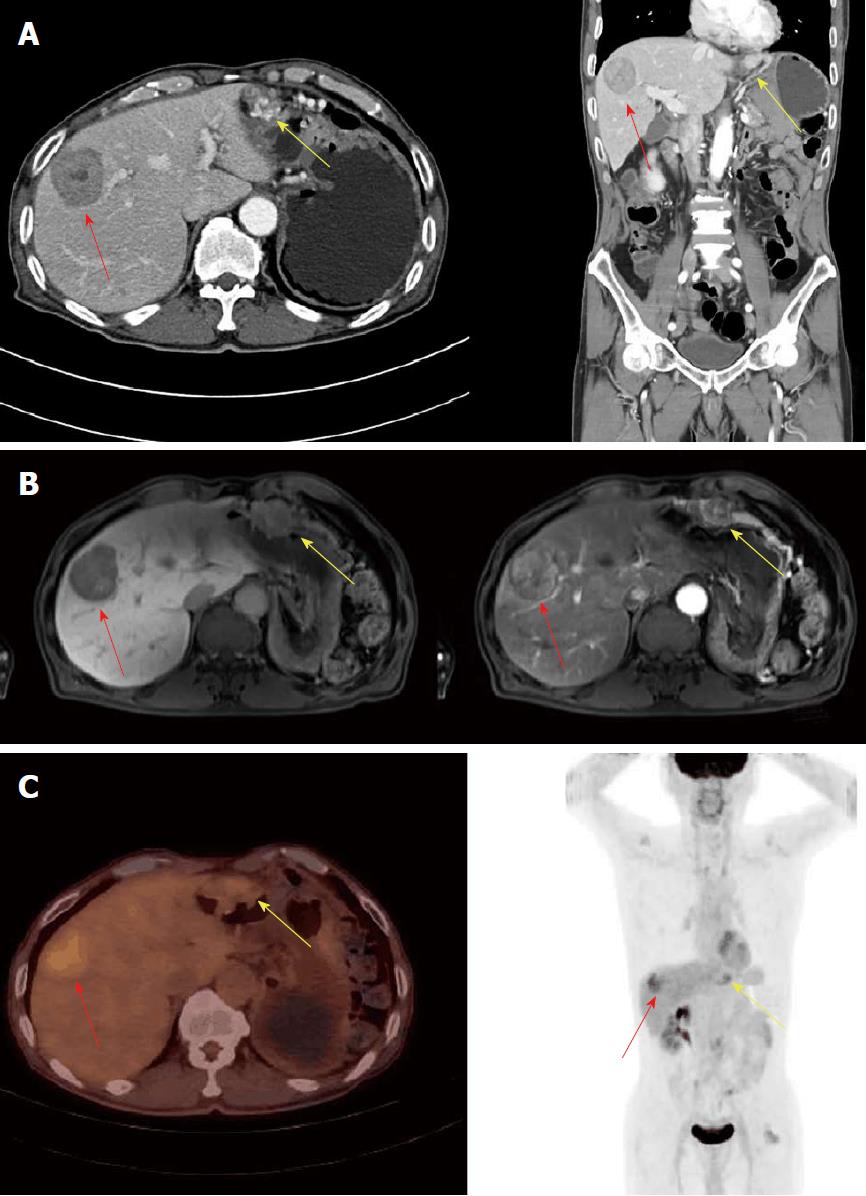

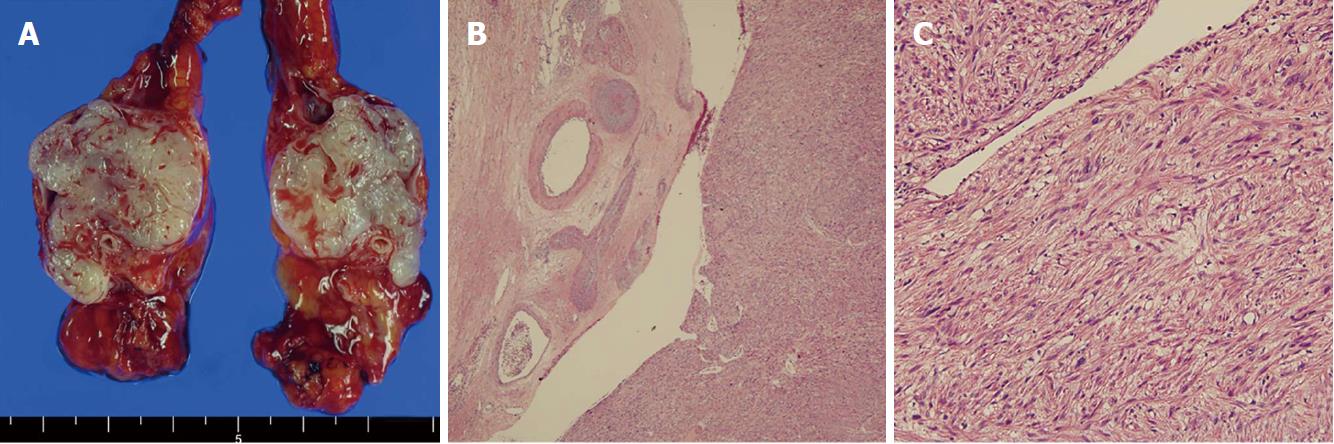

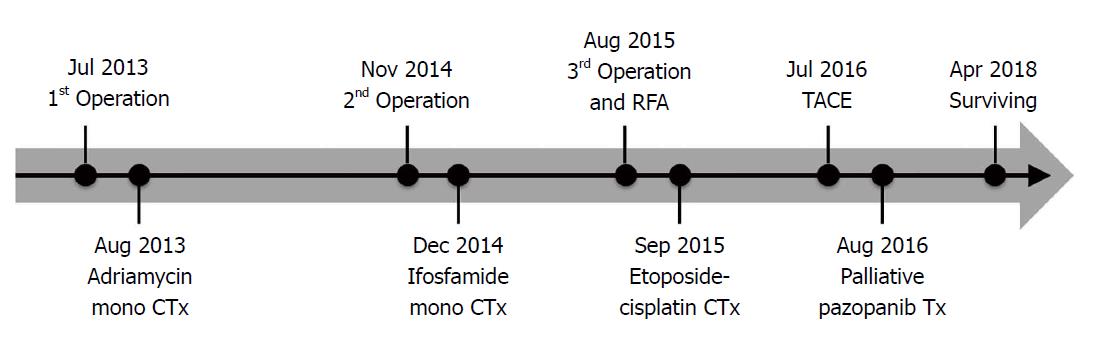

This case involves a 70-year-old man who had a previous operation history due to renal cell carcinoma and rectal cancer (pT2N0M0, stage IIA), ten years and six months ago. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) performed six months after the low anterior resection revealed a new 47 mm hypodense hepatic mass and a 23 mm hypervascular mass at the great curvature side of stomach (Figure 1A and 1B). It was highly suspected to be a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with hepatic metastasis. Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) demonstrated a hypermetabolic low-density lesion in S8 of the liver and the greater curvature of the stomach with a maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) of 3.4 and 2.3, respectively (Figure 1C). For confirmation of the diagnosis, we planned to perform an ultrasonography-guided core needle biopsy. The core needle biopsy specimen of the liver mass showed malignant spindle cell with increased mitosis (7/10 HPFs). Immunohistochemistry results were positive for desmin and smooth muscle actin (SMA) and negative for CD34, c-kit, DOG-1, S-100, and HMB45. These findings suggest that aLMS was the proper diagnosis, not GIST. The mass in the greater curvature of the stomach showed high vascularity upon endoscopic ultrasonography. Therefore, a fine needle aspiration biopsy was not performed because of a bleeding risk. Laparotomy was performed with a diagnosis of the omental GIST and primary hepatic LMS. The omental mass resection and S8 segmentectomy were performed. The omental mass originated from the right gastroepiploic artery on surgical and microscopic field. This mass was a 3.0 cm × 2.7 cm sized aLMS (Figure 2A and 2B). Histopathology showed moderate cellular atypia, high mitotic rate (10/10 HPFs), and 2/3 histologic grade according to the FNCLCC grading system. Ki-67 proliferation index was 4.1% (Figure 2C). Immunohistochemistry results were positive for CD34, CD31, desmin, and SMA and negative for c-kit, DOG-1, and S-100. The liver mass was a 5.0 cm × 3.0 cm × 1.5 cm sized metastatic aLMS with a clear resection margin (free margin: 0.3 cm). Ki-67 proliferation index was 9.3%. The patient was discharged on the nine days after the operation without any complications. It was planned that four cycles of adriamycin monochemotherapy would be administered as an adjuvant treatment. However, treatment was stopped after the third treatment because of neutropenic fever.

Abdominal CT was performed every three months after the operation to check for recurrence. At fourteen months after the first operation, CT and MRI revealed a 2.7 cm, a 5 mm, and an 8 mm sized metastatic masses on of the liver. No extrahepatic metastasis was noted on FDG PET/CT. Right anterior sectionectomy was performed fifteen months after the first operation. There were a 3.0 cm × 2.7 cm and a 1.0 cm × 1.0 cm sized metastatic vascular LMSs. Histopathology and immunohistochemistry showed a high mitotic rate (22/10 HPFs) and a Ki-67 proliferation index of 4.1%. The resection margin was very close to the mass (< 1 mm). Ifosfamide monochemotherapy was administered after the surgery for four cycles.

At eight months after the second operation, CT, MRI and FDG PET/CT revealed a 1.6 cm and a 1.4 cm sized seeding metastatic nodules on the diaphragm and the liver. Diaphragm partial resection and intra-operative RFA was performed nine months after the second operation (twenty-four months after the first operation). The diaphragm mass was also diagnosed as a metastatic vascular LMS. Etoposide-cisplatin chemotherapy was administered after the surgery for six cycles.

At eleven months after the third operation, there were multiple recurrences in the remnant liver as shown by MRI and TACE (2 mL lipiodol and 10 mg adriamycin)

Palliative pazopanib was also started. The patient has been followed for twenty-eight months after the third operation (fifty-three months after the first operation). He is surviving with stable hepatic metastasis controlled by chemotherapy. Treatment modalities are summarized in Figure 3.

Over half of aLMS cases originate from the pulmonary artery, followed by the extra-abdominal peripheral artery. Including this case, only nine cases of aLMS originating from the intra-abdominal arteries, excluding the aorta, have been reported (Table 1)[2-9].

| Ref. | Sex | Age (yr) | Site | Symptom | Treatment | Metastasis | Follow-up |

| Hopkins[2] (1968) | M | 55 | Common iliac | Claudication | Surgery | - | Died after 3 wk |

| Birkenstock et al[3] (1976) | M | 55 | Common iliac | Pain, palpable mass | Surgery | - | No evidence of disease |

| Stringer[4] (1977) | M | 49 | IMA | Pain, palpable mass | Surgery, RTx, CTx | Lung | Died after 7 yr |

| Gutman et al[5] (1986) | F | 55 | Common iliac | Claudication | Surgery | - | No evidence of disease |

| Delin et al[6] (1990) | F | 72 | Common iliac | Claudication, pain | Surgery | - | Died after 7 mo |

| Gill et al[7] (2000) | F | 76 | Renal | Pain | Surgery | - | Follow up for 9 mo |

| Rohde et al[8] (2001) | F | 51 | Splenic | Pain, weight loss | Surgery + CTx (adriamycin + ifosphamide) | - | Follow up for 1 yr |

| Blansfield et al[9] (2003) | F | 42 | Common iliac | Pain | Surgery | - | No evidence of disease |

| Current case | M | 70 | Right gastroepiploic | None | Multimodal | Liver | follow up for 36 mo |

Compared to the other origin of LMS, the case of vascular LMS has a worse prognosis. In the case of LMS with metastasis, metastatic vascular LMS shows similar results as metastatic LMS of other origins[1]. However, the prognosis is not well-known owing to the low number of cases in aLMS. It is presumed that aLMS may be more aggressive than LMS, and hence, the prognosis is expected to be about the same or worse[1]. Because aLMS is more aggressive than LMS, and directly seed to artery, it has a higher possibility of metastasis[10].

Clinical signs of aLMS are diverse depending on the area of origin and most of them are due to the mass effect[9,10]. In this case, the 3 cm primary mass was located in the intra-abdominal area. The patient had no symptoms owing to aLMS. Although, the size of the primary cancer of the right gastroepiploic artery was 3 cm, which was small, it was accompanied by a distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis.

For diagnostic confirmation, a biopsy is needed, and radiological assisted core needle biopsy is preferred over open biopsy because there is a low risk of complications[10]. However, like this case, if the mass is located in the intra-peritoneal region and shows hypervascularity, bleeding could occur after the core needle biopsy. Moreover, bleeding control could be difficult in this location. PET-CT showed SUVmax values of 3.4 and 2.3 each, which had relatively low uptake at first, and uptake was not noted at the lesion recurrence. More precise imaging studies are needed to overcome this limitation.

There are reports of treating LMS cases with surgical resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy[1,4,6,9]. Chemotherapy or chemoembolization has been the main treatment of LMS with hepatic metastasis[10]. Recently, RFA also shows a good result for metastatic LMS[10]. However, recently, just like in other cases of metastatic cancer, liver resection shows better results[11]. If a resection of metastasis is possible, surgical treatment and additional treatment including chemotherapy can lead to a good response.

Although aLMS showed aggressive clinical features, multimodal treatment (resection, chemotherapy, RFA, chemoembolization, and targeted therapy) might be helpful to manage this kind of disease.

A 70-year-old man presented with an intra-abdominal mass and a hepatic mass during a follow visit for rectal cancer surgery.

After CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), it was diagnosed as a malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) with hepatic metastasis.

After the core needle biopsy of the liver, it was diagnosed as a leiomyosarcoma (LMS). Before the surgery, these were omental GIST and hepatic LMS.

At first, it was diagnosed a omental GIST and hepatic metastasis in CT and MRI.

The surgical specimen diagnosed as an aLMS with hepatic metastasis.

Multimodal treatments were done (three surgeries, chemotherapy, transarterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency, and targeted therapy).

There were only nine reports about intra-abdominal arterial leiomyosarcoma (aLMS). This is the first report of intra-abdominal aLMS with hepatic metastasis.

aLMS is a very rare and aggressive disease. The prognosis is very poor. There were few reports of this disease. So the treatment is also not established.

Active treatments using multiple modalities may be helpful for these kinds of patients.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research, and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D, D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aoki H, Mayir B, Meshikhes AWN, Handra-Luca A S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Italiano A, Toulmonde M, Stoeckle E, Kind M, Kantor G, Coindre JM, Bui B. Clinical outcome of leiomyosarcomas of vascular origin: comparison with leiomyosarcomas of other origin. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:1915-1921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hopkins GB. Leriche syndrome associated with leiomyosarcoma of the right common iliac artery. JAMA. 1968;206:1789-1790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birkenstock WE, Lipper S. Leiomyosarcoma of the right common iliac artery: a case report. Br J Surg. 1976;63:81-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Stringer BD. Leiomyosarcoma of artery and vein. Am J Surg. 1977;134:90-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gutman H, Haddad M, Zelikovski A, Mor C, Reiss R. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the right common iliac artery--a rare finding and a cause of occlusive vascular disorder. J Surg Oncol. 1986;32:193-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Delin A, Johansson G, Silfverswärd C. Vascular tumours in occlusive disease of the iliac-femoral vessels. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1990;4:539-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gill IS, Hobart MG, Kaouk JH, Abramovich CM, Budd GT, Faiman C. Leiomyosarcoma of the main renal artery treated by laparoscopic radical nephrectomy. Urology. 2000;56:669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Rohde HT, Riesener KP, Büttner R, Schumpelick V. [Leiomyosarcoma of the splenic artery]. Chirurg. 2001;72:844-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Blansfield JA, Chung H, Sullivan TR Jr, Pezzi CM. Leiomyosarcoma of the major peripheral arteries: case report and review of the literature. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17:565-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gravel G, Yevich S, Tselikas L, Mir O, Teriitehau C, De Baère T, Deschamps F. Percutaneous thermal ablation: A new treatment line in the multidisciplinary management of metastatic leiomyosarcoma? Eur J Surg Oncol. 2017;43:181-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lang H, Nussbaum KT, Kaudel P, Frühauf N, Flemming P, Raab R. Hepatic metastases from leiomyosarcoma: A single-center experience with 34 liver resections during a 15-year period. Ann Surg. 2000;231:500-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |