Published online Aug 16, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.192

Peer-review started: May 15, 2018

First decision: June 4, 2018

Revised: June 6, 2018

Accepted: June 30, 2018

Article in press: June 30, 2018

Published online: August 16, 2018

Processing time: 93 Days and 6.9 Hours

To assess the impact of hepatitis B surface (HBsAg) seroclearance on survival outcomes in hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer.

Information from patients with hepatitis B-related liver cancer admitted in our hospital from 2008-2017 was retrieved. Cases diagnosed with HBsAg (-) and HBcAb (+) liver cancer were included in the HBsAg seroclearance (SC) group. HBsAg (+) liver cancer patients strictly matched for liver cancer stage (AJCC staging system, 8th edition), Child-Pugh score, and first diagnosis/treatment method (surgery, ablation and TACE) were assigned to the HBsAg non-seroclearance (NSC) group. Then, clinical, pathological and survival data in both groups were assessed.

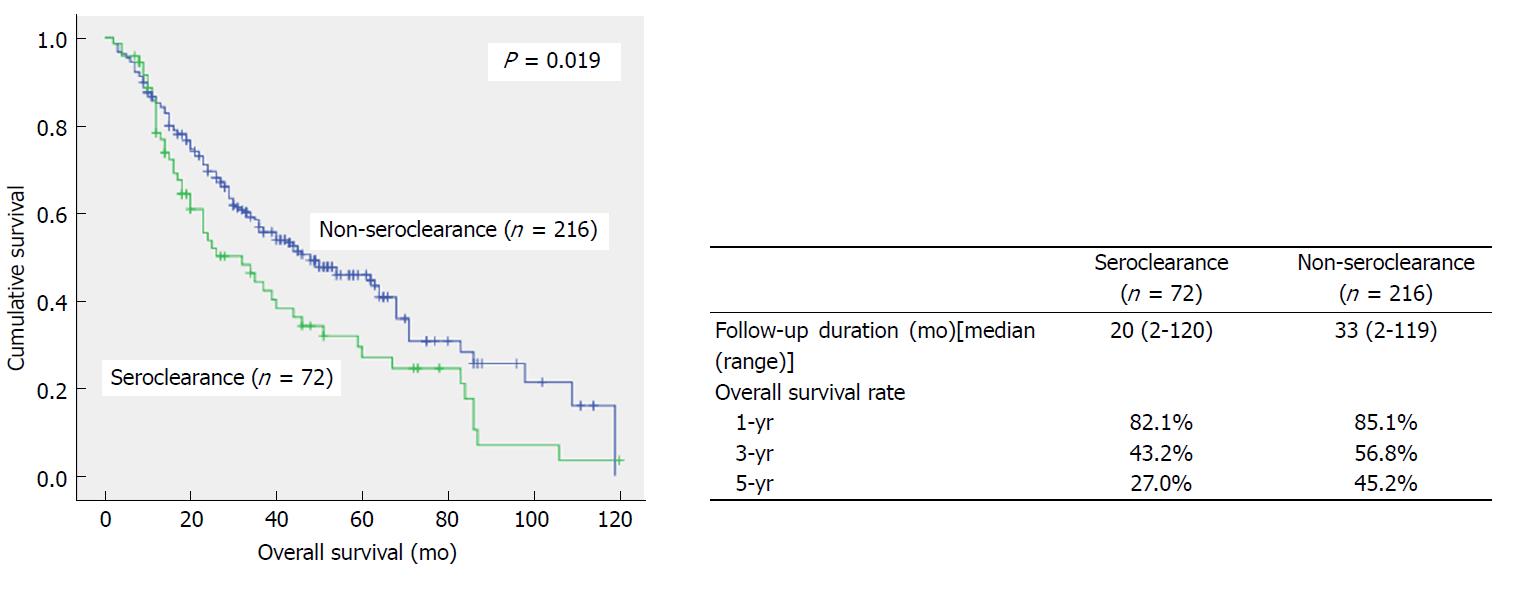

The SC and NSC groups comprised of 72 and 216 patients, respectively. Patient age (P < 0.001) and platelet count (P = 0.001) in the SC group were significantly higher than those of the NSC group. SC group patients who underwent surgery had more intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and combined HCC-CC (CHC) cases than the NSC group, but no significant differences in tumor cell differentiation and history of liver cirrhosis were found between the two groups. The numbers of interventional treatments were similar in both groups (4.57 vs 5.07, P > 0.05). Overall survival was lower in the SC group than the NSC group (P = 0.019), with 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates of 82.1% vs 85.1%, 43.2% vs 56.8%, and 27.0% vs 45.2%, respectively. Survival of patients with AJCC stage I disease in the SC group was lower than that of the NSC group (P = 0.029).

Seroclearance in patients with hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer has protective effects with respect to tumorigenesis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension but confers worse prognosis, which may be due to the frequent occurrence of highly malignant ICC and CHC.

Core tip: Through strict case-control, we eliminated prognostic confounding factors, such as tumor stage, Child-Pugh score, and therapeutic mode, to determine the impact of hepatitis B surface (HBsAg) seroclearance (SC) on the prognosis of HBV related liver cancer,. Statistical analysis shows that although HBsAg SC is protective in tumorigenesis, liver cirrhosis, and portal hypertension, the prognosis of HBsAg SC patients with primary liver cancer is worse than that of controls.

- Citation: Lou C, Bai T, Bi LW, Gao YT, Du Z. Negative impact of hepatitis B surface seroclearance on prognosis of hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(8): 192-199

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i8/192.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i8.192

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) is the most common cause of liver cancer in Asia, especially in China. In Asia, about 60% of liver cancer cases are associated with HBV infection[1]. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance is considered the gold standard for hepatitis B viral clearance and chronic hepatitis B cure, and is now regarded as the end point of antiviral therapy[2,3]. Approximately 0.1%-0.8% of adult patients with chronic HBV infection achieve HBsAg seroclearance in the course of natural development[4,5]. Antiviral therapy could also lead to HBsAg seroclearance in some patients, improving the clinical outcome of individuals with chronic hepatitis B infection[6,7].

After HBsAg seroclearance in these patients, the liver retains very low HBVDNA levels. Compared with chronic hepatitis B patients with positive HBsAg, a further decrease of HBVDNA in vivo results in significantly improved liver histology and biochemistry. However, the incidence of liver cancer remains in patients with seroclearance[5,6,8,9]. A history of cirrhosis and age above 50 years at HBsAg seroclearance are high risk factors for liver cancer[10,11]. Existing studies have confirmed that HBV seroclearance could effectively improve the prognosis of liver cancer patients with positive HBsAg[12,13]. However, whether HBsAg seroclearance, which indicates a further decrease in viral load, affects the prognosis of patients with liver cancer remains unclear. Because of the small number of such cases, it is currently difficult to have an effective patient control group, leading to few studies in this field. Moreover, inconclusive findings have been reported by the small amount of studies available[14].

In this study, the clinicopathological characteristics of liver cancer patients with HBsAg seroclearance were assessed with strict case control and elimination of confounding factors. The correlation between HBsAg seroclearance and the prognosis of patients with liver cancer was established.

Patients with primary liver cancer admitted to our hospital from 2008 to 2017 were included. Hepatitis markers, auto-antibodies in liver disease, drinking history, and other etiological data were recorded. Patients with underlying liver diseases (hepatitis C virus, autoimmune liver disease, alcoholic liver disease, cryptogenic cirrhosis and hepatolithiasis) were excluded. Serum HBV DNA levels are routinely detected in HCC patients with HBsAg (-) and HBcAb (+) except for occult hepatitis B (OHB). Then liver cancer patients characterized by HBsAg (-) and HBcAb (+) were selected as the HBsAg seroclearance (SC) group. Those with HBsAg (+) constituted the HBsAg non-seroclearance (NSC) group. According to the consistent principles of the Child-Pugh scoring system for liver function and the 8th edition of the AJCC/UICC staging system for liver cancer and treatment methods, patients in the SC group were strictly matched with those of the NSC group at a proportion of 1:3. According to Child-Pugh scores, the patients were divided into three grades, including A, B, and C. Based on the initial treatment after diagnosis, the patients were divided into surgical resection, ablation, and TACE groups. According to the 8th edition of the AJCC/UICC staging system for liver cancer, the patients were divided into stages I, II, III, and IV. To accurately reflect treatment responses and the prognosis of patients with liver cancer, AJCC stage IV cases were excluded. Meanwhile, in the TACE group, only the patients who received at least two intervention treatments were selected, which fully reflected TACE efficacy.

The hepatitis B status in all patients was determined at diagnosis. HBsAg status was re-examined after the initial treatment and during follow-up. Serum HBsAg was tested quantitatively [Architect assay, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, Illinois, United States; lower limit of detection (LLOD), 0.05 IU/mL]. Serum HBV DNA levels were measured by using a real-time PCR assay (Roche Laboratories; Basel, Switzerland; LLOD, 100 IU/mL). Before the initial treatment, routine examinations, including routine blood tests, liver function, coagulation function tests, serum-alpha fetoprotein assessment, abdominal ultrasound, contrast ultrasound, enhanced CT, and/or enhanced MRI were performed to determine the diagnosis of liver cancer, tumor size and number, the status of macrovascular invasion, and distant metastasis, as well as liver cancer stage (8th edition of the AJCC/UICC staging system for liver cancer). Patients treated by surgery were routinely examined by ICG. According to liver cancer stage, Child-Pugh score, liver volume obtained from CT scan, ICG findings, and patient willingness, the subjects were respectively selected to undergo surgical excision, ablation therapy, or TACE after the initial diagnosis. Tumor pathology, cell differentiation, underlying liver disease, and other parameters were recorded after surgery. The numbers of interventional treatments in the TACE group were recorded.

All patients were followed up after treatment, and overall survival (OS) was the only main evaluation index. The initial diagnostic time of liver cancer was used as the starting time. The deadline for follow up was December 31, 2017, and survival time was recorded.

Continuous data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Tumor size and follow-up time were represented by median. T-test was used for comparison. Count data were expressed as frequency and proportion, and assessed by the χ2 test. The Kaplan-Meier method was used for survival analysis, and the log-rank test for comparison.

The clinical data of liver cancer patients in a single center for ten years were retrieved. Of the 4745 patients with liver cancer, there were 1772 cases of hepatitis B-related liver cancer. Among them, 91 cases were diagnosed as liver cancer patients with HBsAg seroclearance, accounting for 5.14% (91/1772), of which five patients were excluded from the analysis due to incomplete data or loss to follow-up. Considering the short life span of patients with advanced liver cancer and poor therapeutic responses, six AJCC stage IV liver cancer patients were excluded, and eight additional patients were excluded for only receiving a single TACE treatment, which was not suitable for evaluating treatment efficacy. Finally, the clinical data of 72 patients with liver cancer in the SC group were collected. The serum HBVDNA levels of patients in the SC group were all negative and OHC were excluded. Meanwhile, 216 matched patients in the NSC group were enrolled according to a proportion of 1:3.

The baseline characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 1. Median patient age in the SC group was significantly higher than that of the NSC group (63.5 ± 8.9 years vs 57.0 ± 9.0 years, P < 0.001). Due to Child-Pugh score matching, there were no significant differences in coagulation, albumin, and bilirubin between the two groups, but platelet levels in the SC group were significantly higher than those of the NSC group (163.2 ± 87.5 vs 126.7 ± 76.2, P = 0.001).

| Variables | Seroclearance (n = 72) | Non-seroclearance (n = 216) | P value |

| Ages [median (range)] | 63.5 ± 8.9 | 57.0 ± 9.0 | < 0.001 |

| Sex (male:female) | 59:17 | 171:45 | 0.871 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 130.6 ± 28.0 | 135.3 ± 21.7 | 0.144 |

| Platelet count (× 109/µL) | 163.2 ± 87.5 | 126.7 ± 76.2 | 0.001 |

| PTA (%) | 90.5 ± 20.7 | 87.7 ± 18.5 | 0.282 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.5 ± 5.6 | 40.1 ± 5.9 | 0.675 |

| AST (IU/L) | 33.3 ± 28.6 | 39.9 ± 36.7 | 0.163 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 36.9 ± 40.7 | 42.4 ± 41.7 | 0.327 |

| TBil (µmol/L) | 21.2 ± 20.9 | 19.8 ± 17.5 | 0.567 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | |||

| ≤ 15 | 36 | 100 | 0.456 |

| 15-200 | 19 | 54 | |

| ≥ 200 | 17 | 62 | |

| Size of tumor (cm) [median (range)] | 5.4 (1-15.4) | 4.35 (1-15) | 0.064 |

| Number of tumor nodules | |||

| Solitary | 51 | 138 | 0.318 |

| Multiple | 21 | 78 | |

| Treatment | |||

| Resection | 26 | 78 | - |

| Ablation Tx | 23 | 69 | |

| TACE | 26 | 78 | |

| AJCC 8th edition | |||

| Stage I | 41 | 123 | - |

| Stage II | 9 | 27 | |

| Stage III | 22 | 66 | |

| Child-Pugh grade | |||

| A | 67 | 171 | - |

| B | 14 | 42 | |

| C | 1 | 3 |

Stratification was carried out according to the treatment method, with 26 patients and 78 patients treated by surgery in the SC and NSC groups, respectively. The clinical data of the above patients are shown in Table 2. Consistent with the overall data, patient age and platelet levels in the SC group were significantly higher than those of the NSC group. A significant difference was found in pathological types of liver cancer between the two groups (P = 0.002). The SC group had more ICC and CHC cases compared to the NSC group, but there were no significant differences in tumor cell differentiation and history of cirrhosis between the two groups. A total of 23 patients in the SC group were administered interventional therapy, versus 69 patients in the NSC group. Based on this stratification, patients in the SC group also showed differences in age and platelet levels, which was consistent with the overall data. There was no statistical difference in the number of interventional treatments between the two groups (4.57 vs 5.07, P > 0.05), indicating the consistency of intervention intensity.

| Variables | Seroclearance (n = 26) | Non-seroclearance (n = 78) | P value |

| Ages (median) | 61.6 ± 10.1 | 56.4 ± 8.4 | 0.010 |

| Sex (male:female) | 22:6 | 69:9 | 0.216 |

| Hemoglobin (mg/dL) | 138.3 ± 21.0 | 142.1 ± 18.7 | 0.385 |

| Platelet count (× 109/µL) | 197.7 ± 91.6 | 154.8 ± 81.7 | 0.026 |

| PTA (%) | 96.9 ± 16.2 | 94.5 ± 17.8 | 0.538 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 41.8 ± 4.3 | 42.2 ± 4.8 | 0.716 |

| AST (IU/L) | 37.7 ± 39.5 | 42.7 ± 33.9 | 0.529 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 41.4 ± 41.6 | 41.2 ± 46.7 | 0.985 |

| TBil (µmol/L) | 19.7 ± 23.2 | 17.4 ± 14.8 | 0.570 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | |||

| ≤ 15 | 12 | 30 | 0.581 |

| 15-200 | 5 | 23 | |

| ≥ 200 | 9 | 25 | |

| Size of tumor (cm) [median (range)] | 7.2 (2.3-15.4) | 6.1 (2.3-15) | 0.140 |

| Number of tumor nodules | |||

| Solitary | 20 | 49 | 0.235 |

| Multiple | 6 | 29 | |

| Pathological type | |||

| HCC | 18 | 74 | 0.002 |

| ICC | 3 | 2 | |

| CHC | 5 | 2 | |

| Cell differentiated degree | |||

| Highly differentiated | 5 | 13 | 0.180 |

| Moderately differentiated | 11 | 48 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 10 | 17 | |

| Liver cirrhosis | |||

| Yes | 20 | 68 | 0.221 |

| No | 6 | 10 | |

| AJCC 8th edition | |||

| Stage I | 14 | 42 | - |

| Stage II | 2 | 6 | |

| Stage III | 10 | 30 | |

| Child-Pugh grade | |||

| A | 25 | 75 | - |

| B | 1 | 3 | |

| C | 0 | 0 |

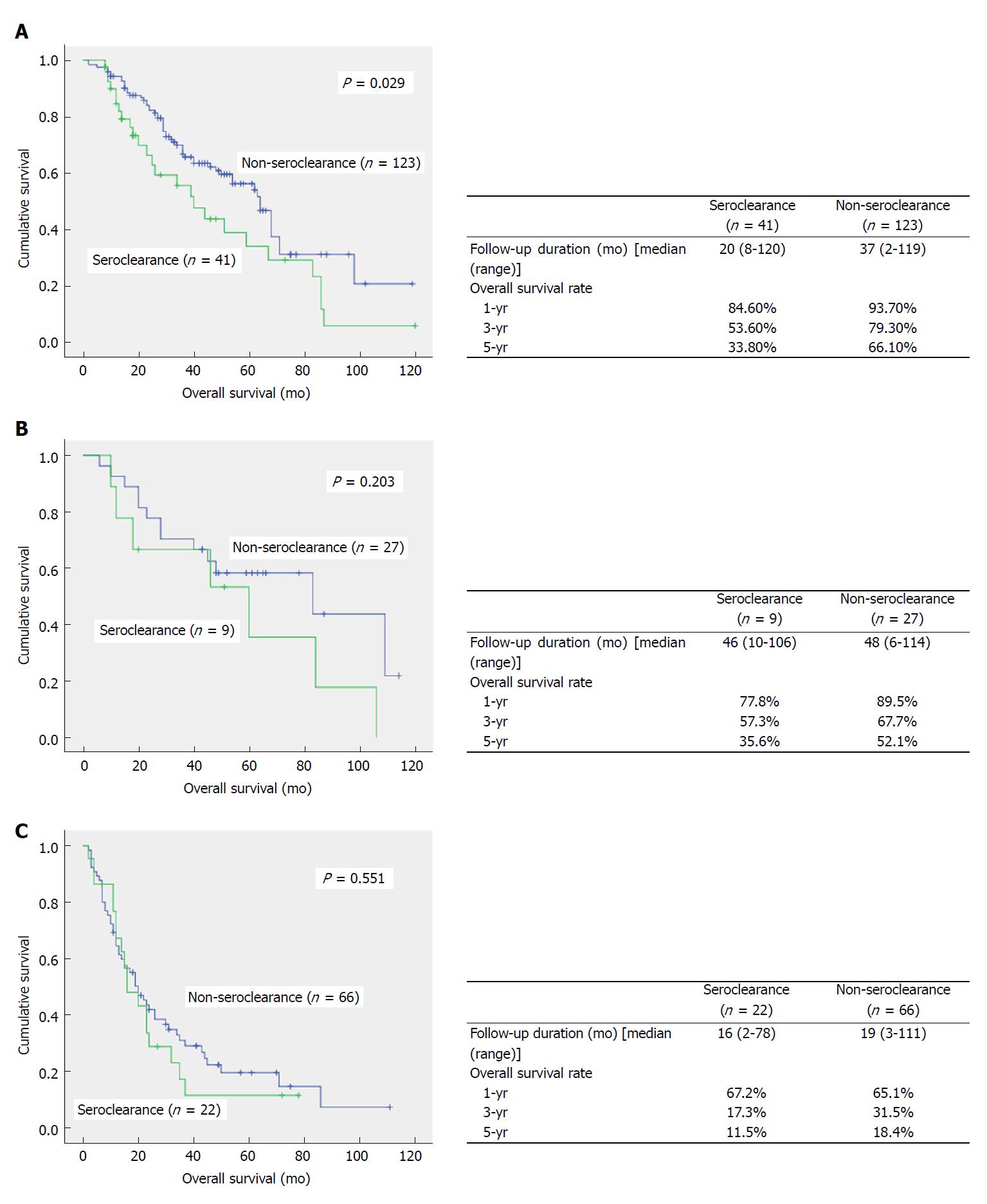

All patients in the SC and NSC groups were followed up, with median follow-up times of 20 mo and 33 mo, respectively, indicating no significant difference between the two groups (P > 0.05). As shown in Figure 1, overall survival in the SC group was lower than that of the NSC group (P = 0.019). The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 82.1%, 43.2% and 27.0% in the SC group, respectively, which were significantly lower than those of the NSC group (85.1%, 56.8%, and 45.2%, respectively). Stratification analysis was further carried out according to tumor stage (Figure 2); overall survival in patients with AJCC stage I disease in the SC group was significantly lower than that of the NSC group (P = 0.029). Meanwhile, the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 84.6%, 53.6% and 33.8% in the SC group, respectively, which were significantly lower than those of the NSC group (93.7%, 79.3%, and 66.1%, respectively). Although AJCC stage II and III patients in the SC group also showed trends of lower survival rates, statistical significance was not achieved.

In the present study, through strict design matching, important confounding factors closely related to survival in patients with liver cancer (such as tumor stage, Child-Pugh score, and treatment method) were eliminated. Then, the effects of HBsAg seroclearance on the clinical characteristics and survival outcome of patients with hepatitis B-related liver cancer were determined. Patients with HBsAg seroclearance accounted for 5.14% (91/1772) of all cases of hepatitis B-related liver cancer in this study. Compared with the NSC group, the patients in the SC group were older and had higher platelet counts, but the overall prognosis of these patients was worse.

Previous studies have shown that the older the liver cancer patient with HBsAg seroclearance, the better the liver function reserve[6,9,14,15]. In the present study, this notion was confirmed by both holistic and subgroup analysis, and patients in the SC group were significantly older. These results indicated a delay in the occurrence of liver cancer, suggesting the protective effects of HBsAg seroclearance. As both groups were matched for Child-Pugh scores, we could not compare liver function between the two groups. However, a significant difference in platelet levels was found between the two groups. Platelet count is a sensitive index of hypersplenism, which indirectly reflects the severity of portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Our results showed that the higher the platelet count, the better the liver function reserve as in previous studies. This also suggests a potential protective effect of HBsAg seroclearance in the liver.

Although the above results confirmed liver protection by HBsAg seroclearance in patients with chronic hepatitis B, the final survival analysis yielded opposite data. Indeed, the prognosis of patients in the SC group was worse than that of the NSC group. Further analysis showed that for liver cancer patients with AJCC stage I disease, the SC group showed worse overall survival compared with the NSC group. Generally, tumors at the early stage are more likely to be curatively treated with better therapeutic efficacy. Therefore, prognosis of these patients could better reflect the biological behavior of the tumor. Based on this common knowledge, the survival results in stageIpatients indicated the higher malignancy of tumors in the SC group. Although subsequent survival analysis of AJCC stage II and III patients showed no statistical significance, the SC group still showed a worse survival trend.

Comparing the pathological types of liver cancer treated with surgery, the two patient groups showed different distributions. The SC group showed more ICC and CHC cases, and malignancy in these two pathological types is obviously higher than that of HCC[16]. Unfortunately, the ablation group was limited by the rate of biopsy in addition to the limitations of puncture pathology itself. Therefore, insufficient data could not be effectively analyzed. Results of the sole operation group could not represent the tumor type characteristics of the whole cohort. However, due to the highly significant difference observed in pathological types for the surgery group, the results were representative. More importantly, these findings corroborated survival data, which could partly explain the worse prognosis of patients with liver cancer in the SC group.

Studies have confirmed that HBV infection is closely related not only to HCC, but also to the incidence and prognosis of ICC[17-19]. In addition, a recent meta-analysis assessing the correlation between the HBV infection status and the risk of cholangiocellular carcinoma showed that consistent with positive HBsAg, HBsAg seroclearance is also a high risk factor for ICC[20]. This was confirmed by the above pathological findings. In another report, 928 patients with hepatitis B-associated ICC were assessed, including 24.7% with chronic hepatitis B and HBsAg seroclearance, and a high incidence of ICC in the SC group was also obtained[21]. Another important surgical and pathological finding in this study was the frequent occurrence of CHC in the SC group. Among twenty-six patients that underwent surgical excision in the SC group, five CHC cases were found, including two also diagnosed with cirrhosis. This pathological type is infrequently represented among all liver cancer cases, accounting for only 1.0%-4.7%. However, its malignancy exceeds that of ICC and HCC[16,22,23]. Zhou et al[24] found that HBV infection is an independent risk factor for CHC, with 64.3% of cases also diagnosed with cirrhosis. Multiple studies have shown that this mixed hepatocarcinoma might be largely derived from hepatic precursor cells (HPCs). Indeed, carcinogenic factors affect the multi-differentiation potential of HPCs, leading to the formation of a mixed source of hepatocytes and cholangiocytes[25-27]. Although previous studies have confirmed the associations of HBV infection with ICC and CHC incidence rates, it is very challenging to understand why these two highly malignant tumors were more likely to occur in the SC group. These findings still require confirmation in large sample trials.

The limitations of the present study should be mentioned. First, this was a single center retrospective case control study, with a possibility of selection bias in the control group. Second, since liver cancer incidence in patients with HBsAg seroclearance is low, the sample size was limited, and the number of cases after stratification was even more reduced, which resulted in wide confidence intervals. Third, because of difficulties in tracing the disease history, the current study lacked key data such as time of antiviral treatment, time of HBsAg seroclearance, and time of cirrhosis diagnosis. The correlation of HBsAg seroclearance with cirrhosis and liver cancer occurrence could not be well explained. Multicenter prospective studies are needed to solve the above problems.

In conclusion, patients with HBsAg seroclearance still have a risk of developing liver cancer. Although HBsAg seroclearance has some protective effects in respect to tumorigenesis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension, prognosis in these patients is worse, likely because of the frequent occurrence of highly malignant ICC and CHC.

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) seroclearance is considered the gold standard for hepatitis B virus (HBV) clearance and chronic hepatitis B cure. Existing studies have confirmed that HBsAg seroclerance could result in significantly improved liver histology and biochemistry in patients with chronic HBV, but a certain incidence of liver cancer still exists. The current question is whether HBsAg seroclerance plays a role in the prognosis of liver cancer patients. Due to the small number of such patients, there is currently no reliable research and conclusion.

The effect of HBsAg seroclearance on prognosis in hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer remains unclear. The solution to this problem would improve the understanding of the etiology and pathogenesis of HBV-related liver cancer and to guide clinical treatment.

Our objective was to assess the impact of HBsAg seroclearance on survival outcomes in hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer.

We designed a case-control study. Information from patients with hepatitis B-related liver cancer admitted to our hospital in 2008-2017 was retrieved. Cases diagnosed with HBsAg (-) andHBcAb (+) liver cancer were included in the HBsAg seroclearance (SC) group. HBsAg (+) liver cancer patients were strictly matched for liver cancer stage (AJCC staging system, 8th edition), Child-Pugh score, and first diagnosis/treatment method (surgery, ablation and TACE) and were assigned to the HBsAg non-seroclearance (NSC) group. Then, clinical, pathological, and survival data in both groups were assessed.

The SC and NSC groups comprised of 72 and 216 patients, respectively. Patient age (P < 0.001) and platelet count (P = 0.001) in the SC group were significantly higher than those of the NSC group. SC group patients who underwent surgery had more intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) and combined HCC-CC (CHC) cases than the NSC group, but no significant differences in tumor cell differentiation and history of liver cirrhosis were found between the two groups. Overall survival was lower in the SC group than the NSC group (P = 0.019). Survival of patients with AJCC stage I disease in the SC group was lower than that of the NSC group (P = 0.029).

Seroclearance in patients with hepatitis B-related primary liver cancer has protective effects with respect to tumorigenesis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension but confers worse prognosis, likely due to the frequent occurrence of highly malignant ICC and CHC.

This is the first reliable study about the effect of HBsAg seroclearance on the prognosis of hepatitis B-related liver cancer. In the future, more SC patients should be accumulated, and it is necessary to further verify this result by propensity score matching.

The authors thank Dr. Qi Xin for assistance with data analysis and Mrs. Xu-xia Li for assistance with data collection.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Aghakhani A, Ahmed Said ZN, Kanda T, Sazci A S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Iavarone M, Colombo M. HBV infection and hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Liver Dis. 2013;17:375-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chong CH, Lim SG. When can we stop nucleoside analogues in patients with chronic hepatitis B? Liver Int. 2017;37 Suppl 1:52-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2400] [Article Influence: 184.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Liaw YF, Sheen IS, Chen TJ, Chu CM, Pao CC. Incidence, determinants and significance of delayed clearance of serum HBsAg in chronic hepatitis B virus infection: a prospective study. Hepatology. 1991;13:627-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Simonetti J, Bulkow L, McMahon BJ, Homan C, Snowball M, Negus S, Williams J, Livingston SE. Clearance of hepatitis B surface antigen and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort chronically infected with hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2010;51:1531-1537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kim GA, Lim YS, An J, Lee D, Shim JH, Kim KM, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Suh DJ. HBsAg seroclearance after nucleoside analogue therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B: clinical outcomes and durability. Gut. 2014;63:1325-1332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 252] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Liu F, Wang XW, Chen L, Hu P, Ren H, Hu HD. Systematic review with meta-analysis: development of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients with hepatitis B surface antigen seroclearance. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;43:1253-1261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Liu J, Yang HI, Lee MH, Lu SN, Jen CL, Batrla-Utermann R, Wang LY, You SL, Hsiao CK, Chen PJ. E.V.E.A.L.-HBV Study Group. Spontaneous seroclearance of hepatitis B seromarkers and subsequent risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2014;63:1648-1657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yuen MF, Wong DK, Fung J, Ip P, But D, Hung I, Lau K, Yuen JC, Lai CL. HBsAg Seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B in Asian patients: replicative level and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1192-1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 321] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kim JH, Lee YS, Lee HJ, Yoon E, Jung YK, Jong ES, Lee BJ, Seo YS, Yim HJ, Yeon JE. HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B: implications for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:64-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim GA, Lee HC, Kim MJ, Ha Y, Park EJ, An J, Lee D, Shim JH, Kim KM, Lim YS. Incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma after HBsAg seroclearance in chronic hepatitis B patients: a need for surveillance. J Hepatol. 2015;62:1092-1099. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hosaka T, Suzuki F, Kobayashi M, Seko Y, Kawamura Y, Sezaki H, Akuta N, Suzuki Y, Saitoh S, Arase Y. Long-term entecavir treatment reduces hepatocellular carcinoma incidence in patients with hepatitis B virus infection. Hepatology. 2013;58:98-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 540] [Article Influence: 45.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zoutendijk R, Reijnders JG, Zoulim F, Brown A, Mutimer DJ, Deterding K, Hofmann WP, Petersen J, Fasano M, Buti M. Virological response to entecavir is associated with a better clinical outcome in chronic hepatitis B patients with cirrhosis. Gut. 2013;62:760-765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yip VS, Cheung TT, Poon RT, Yau T, Fung J, Dai WC, Chan AC, Chok SH, Chan SC, Lo CM. Does hepatitis B seroconversion affect survival outcome in patients with hepatitis B related hepatocellular carcinoma? Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moucari R, Korevaar A, Lada O, Martinot-Peignoux M, Boyer N, Mackiewicz V, Dauvergne A, Cardoso AC, Asselah T, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. High rates of HBsAg seroconversion in HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B patients responding to interferon: a long-term follow-up study. J Hepatol. 2009;50:1084-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weber SM, Ribero D, O’Reilly EM, Kokudo N, Miyazaki M, Pawlik TM. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: expert consensus statement. HPB (Oxford). 2015;17:669-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 33.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou HB, Hu JY, Hu HP. Hepatitis B virus infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5721-5729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lei Z, Xia Y, Si A, Wang K, Li J, Yan Z, Yang T, Wu D, Wan X, Zhou W. Antiviral therapy improves survival in patients with HBV infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma undergoing liver resection. J Hepatol. 2017;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tao LY, He XD, Xiu DR. Hepatitis B virus is associated with the clinical features and survival rate of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:682-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang H, Zhu B, Zhang H, Liang J, Zeng W. HBV Infection Status and the Risk of Cholangiocarcinoma in Asia: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:3417976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sha M, Jeong S, Xia Q. Antiviral therapy improves survival in patients with HBV infection and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma undergoing liver resection: Novel concerns. J Hepatol. 2018;68:1315-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Yeh MM. Pathology of combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25:1485-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee JH, Chung GE, Yu SJ, Hwang SY, Kim JS, Kim HY, Yoon JH, Lee HS, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Long-term prognosis of combined hepatocellular and cholangiocarcinoma after curative resection comparison with hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zhou YM, Zhang XF, Wu LP, Sui CJ, Yang JM. Risk factors for combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma: a hospital-based case-control study. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:12615-12620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Theise ND, Yao JL, Harada K, Hytiroglou P, Portmann B, Thung SN, Tsui W, Ohta H, Nakanuma Y. Hepatic ‘stem cell’ malignancies in adults: four cases. Histopathology. 2003;43:263-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Suzuki A, Sekiya S, Onishi M, Oshima N, Kiyonari H, Nakauchi H, Taniguchi H. Flow cytometric isolation and clonal identification of self-renewing bipotent hepatic progenitor cells in adult mouse liver. Hepatology. 2008;48:1964-1978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang J, Shen L, Lu Y, Li H, Zhang X, Hu D, Feng T, Song F. Parallel induction of cell proliferation and inhibition of cell differentiation in hepatic progenitor cells by hepatitis B virus X gene. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:842-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |