Published online Mar 16, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i3.27

Peer-review started: December 21, 2017

First decision: January 3, 2018

Revised: January 5, 2018

Accepted: February 4, 2018

Article in press: February 4, 2018

Published online: March 16, 2018

Processing time: 82 Days and 19.4 Hours

To compare the efficacy of resin composite restorations, retained with either polyethylene or zirconia-rich glass fiber posts.

Sixty-two single rooted maxillary and mandibular central incisor teeth in forty-four patients (15 males and 29 females; age range 15-32 years) were restored either with an ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWP) fiber post (Bondable Reinforcement Ribbon, DENSE, Ribbond, Seattle, WA, United States) or a zircon-rich glass fiber post (Snowpost, Lot H 040; Carbotech, Ganges, France). Then, direct resin composite restoration (Clearfil AP-X, Kuraray) was performed for both post systems in tooth color suitable. Patients were recalled for routine inspections at 6 mo, 1, 2 and 3 years.

The restorations were assessed during each recall evaluation according to predetermined clinical and radiographic criteria (periapical lesion; marginal leakage and integrity; color stability; surface stain and loss of retention of the post or the composite build-up material). The follow-up data showed no significant difference in these criteria between polyethylene fibre posts and zirconia-rich glass fibre posts.

The efficacy of resin composite restorations, retained with either polyethylene or zirconia-rich glass fiber posts were similar, suggesting that both types of fiber post can be used successfully to help retain resin composite restorations.

Core tip: The results of our study showed that both administrations were equally successful in the 36-mo clinical follow-up. Composite-zircon-dentin-post-core monoblock are clinically successful as polyethylene fiber posts. In summary, after 36 mo of follow-up observation, 62 endodontically treated central incisors with partial crown loss that had been restored with polyethylene fibre or zirconia-rich glass fibre posts and direct resin composite exhibited favourable clinical outcomes. The combined use of fibre posts and composite materials is an efficient alternative to conventional courses of treatment for endodontically treated anterior teeth.

- Citation: Ayna B, Ayna E, Çelenk S, Başaran EG, Yılmaz BD, Tacir İH, Tuncer MC. Comparison of the clinical efficacy of two different types of post systems which were restored with composite restorations. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(3): 27-34

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i3/27.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i3.27

The aesthetic demands of patients have made the use of tooth-coloured post systems compulsory for metal-free aesthetic restorations. Ceramic, polyethylene, quartz, and glass-fibre posts are the most popular systems[1-6].

These systems have become successful because few tooth fractures were observed after endodontically treated teeth were restored with a fiber post[2,6-8].

Fibre-reinforced polymer posts are made of carbon or silica fibres, surrounded by a matrix of polymer resin, usually an epoxy resin[9]. While two in vitro studies[10,11] have shown that fibre-reinforced posts are significantly weaker than cast-metal posts and cores, the rigidity of the metal may present a higher risk of root fracture. The lower flexural modulus of fibre-reinforced posts (1 × 106 to 4 × 106 psi) more closely approximates that of dentin (= 2 × 106 psi) and can decrease the incidence of root fracture[11,12].

Since post placement and root canal treatment are the main causes of root fracture, crown covering has been routinely proposed as a preventive measure[2,13-15]. In cases of significant loss of tooth structure, the crown placement was associated with the survival of endodontically treated teeth[2,10,16,17]. However, a recent clinical trial[2] achieved favourable results for the direct restoration of root-canal-treated teeth with fibre posts and composite resin. The nature of the bond between the glass-fibre post and the composite resin core creates a “quasi-monoblock” restoration that effectively integrates with the restored tooth and positively affects the success rate[18].

Two types of fibre-reinforced composites have been advocated for post-and-core systems: prefabricated posts and customised posts[8]. Customised post-and-core build-ups usually consist of glass or polyethylene fibres that are luted directly into the root canal[3,8]. Although this practice of fiber reinforced composites has been announced and used by many dentists, the scientific evidence supporting the application of this material to the dentist is lacking[3]. Furthermore, clinical reports have documented the inadequate performance of fibre posts with direct resin composite restorations although it have indicated successful clinical performance when crown coverage was used after tooth build-up in retrospective studies[2,7,8]. An association between crown placement and the survival of endodontically treated teeth was observed when the lost of tooth structure was remarkable. However the mode of failure or deflection of bonded fiber reinforced composites posts demonstrated that they may protect the remaining tooth structures, particularly since fractures occurs at loads that rarely occur clinically. Although retrospective studies reported good clinical performances when a crown was used after tooth build up, the performance of fiber post when they are use in conjunction with direct resin composite restorations remain largely unreported. This preliminary report compared the survival rate of endodontically treated teeth restored using two fibre post systems, prefabricated zirconia-rich glass fibre posts and customised polyethylene fibre-reinforced posts, and direct resin composite restoration without additional crown coverage. The null hypothesis posited that no significant difference would be found in the clinical performances of teeth restored with prefabricated zirconia-rich glass fibre posts and those restored with customised polyethylene fibre-reinforced posts.

Sixty-two single-rooted maxillary and mandibular central incisors (included if at least 50% of residual sound toot structure was present) in 44 patients (15 males, 29 females; age range 1532 years) were restored with either an ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWP) fibre post (Bondable Reinforcement Ribbon, DENSE; Ribbond, Seattle, WA, United States) or a zirconia-rich glass fibre post (Snowpost, Lot H 040; Carbotech, Ganges, France). Eighteen patients received restorations on both central incisors, and some patients received both post types. The follow-up observation period was 36 mo.

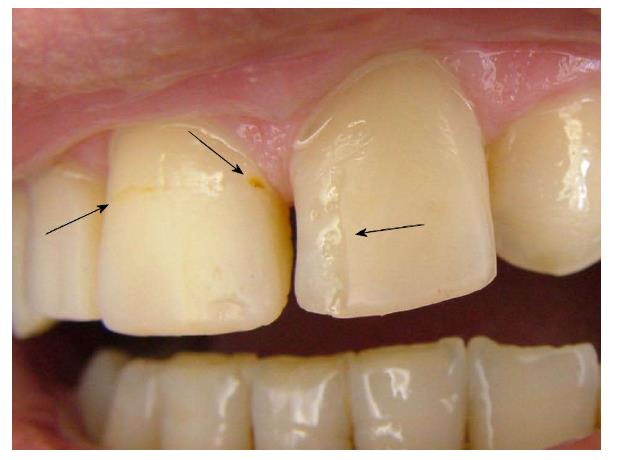

The criteria for inclusion in this study were: clinical and radiographic confirmation of the need for root canal treatment, partial crown loss; satisfaction with the aesthetics and function of the restoration following the placement of root filling, and absence of crown coverage. The patients were randomly assigned to one of two experimental groups according to post type (Figures 1 and 2).

This study was conducted under approval of our ethical committee, and was registered as prospective clinical trial; Dental Faculty Hospital Trial Registry (PRO-3258/2010-13). Informed consent was obtained from the patients before enrolment in the clinical evaluation. Written informed consent form was obtained from parent of children younger than 18 years.

First, the input cavity was prepared and the remaining vital pulp tissue was removed. Root canals were prepared with K-files, irrigated with 2.25% sodium hypochlorite and dried with paper points. After these procedures were completed, a calcium hydroxide paste (Vision, Barmstedt, Germany) with a 8:1 powder-to-glycerin ratio was placed into the root canals with a lentulo filler. The entrance cavities were closed with zinc oxide-eugenol cement and the intracanal dressing was changed for 6 wk. When the teeth do not contain any symptoms, the root canals are dried, and the size of the periapical radiolucency had decreased, the root canals were filled with gutta-percha (Gapadent, Hamburg, Germany) and a root canal sealer (Diaket; 3M ESPE, Seefeld, Germany) by two operators (BA and SÇ) using a lateral condensation technique. The root canals of teeth without periapical lesions were conventionally filled with gutta-percha and a root canal sealer.

All teeth were then prepared in the standard clinical manner by four operators (EA, EGB, İHT, BDY) with rotary instruments. The root canal walls were enlarged to a length of 910 mm with calibrated drills (Gates Glidden), maintaining at least 45 mm of apical seal. The canal walls were then etched for 15 s with 37% phosphoric acid (Kerr Gel Etchant; KerrHawe SA, Bioggio, Switzerland), sprayed with water, and gently air-dried. The excess water was removed from the post space using paper points (Precise Dental Int. SA de CV, Zapopen, Mexico).

The internal surfaces of the root canal and pulp chamber were treated for 30 s with a primer (Liner Bond II V, primer A and B mixture; Kuraray, Osaka, Japan) and air-dried for 15 s. A dual-polymerizing dentin-bonding agent (Liner Bond II V, bond A and B mixture; Kuraray, Osaka, Japan) was applied to the canal and chamber surfaces and thinned with a brush. After the width of the reinforced polyethylene fibre was determined, the prepared dowel space was measured twice with a periodontal probe to determine the length of fibre needed. Two pieces of fibre were then cut with special scissors (Ribbond Shears; Ribbond), coated with a dual-polymerizing resin composite (Liner Bond II V; Kuraray), and placed in a light-protective container. A highly filled, dual-polymerizing hybrid resin (Panavia F; Kuraray) was then injected into the canal space.

One piece of the reinforcement polyethylene fibre (2 mm thickness) that had been coated with bonding agent (Liner Bond II V, bond A and B mixture; Kuraray, Osaka, Japan) was folded and packed as tightly as possible into the canal space using an endodontic plugger. The second piece was packed into the canal space perpendicular to the first piece. Excess resin was then removed, and an incremental technique was used to apply the resin-soaked ribbon (Figure 3).

The zirconia-rich glass fibre posts were conventionally cemented with dual-cure resin cement (Panavia F; Kuraray). Post sizes 1, 2, or 3 were used, according to the diameter of the canal. The posts were cleaned with acetone and silanized with a prehydrolyzed silane solution (Monobond S; Ivoclar Vivadent, Schoon, Lichtenstein) before insertion. Immediately after applying the cement to the post surface with the lentulo spiral, it was inserted directly into the canal. Cement residues were cleaned with a clean microbrush and light cured for 40 s (Figure 4).

Direct resin composite restoration (Clearfil AP-X, Kuraray) was performed for both post systems in tooth color suitable. Opaque dentin and enamel tones and translucent enamel shades were applied freehand by incremental technique. All restorations were shaped and polished with shaping and polishing discs (Sof-Lex, 3M ESPE, St. Paul, MN, United States; Figures 5 and 6) Oral hygiene instructions were given to all patients and a mechanical scaling plus root planing was performed every 6 mo so that the plaque could be removed completely.

Clinical and radiologic evaluation of endodontically treated and restored teeth was performed at the 6th mo and then at the first, second, and third years at routine controls. All restorations were made between April and June 2010. Initial evaluations of the teeth were made in October 2010. The next evaluations were made in April 2011, 2012 and 2013.

During follow-up appointments, the stability and lifespan of the restorations were assessed using the following criteria[2]: (1) Is there a periapical lesion; (2) marginal leakage and integrity; (3) color stability; (4) surface stain; and (5) loss of retention of the post or the composite build-up material. The evaluations were carried out by two operators (EGB, BDY) that did not perform restorations and did not appear when recalled (single blind trial).

The follow-up data were analyzed using the SPSS statistical package (ver. 13.0 for Windows; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Contingency table data were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-squared, continuity correction, Fisher’s exact test, and linear-by-linear association chi-squared tests. P values less than 0.05 were deemed to indicate statistical significance.

After the teeth were restored with a polyethylene or zirconia-rich glass fiber posts and resin composite restorations the presence of periapical lesions, marginal leakage, surface staining, crown retention and color stability were assessed at 6, 12, 24, and 36 mo (Tables 1-5). None of the subjects dropped out of this study. Only seven teeth in the study sample exhibited periapical lesions after 36 mo, and were retreated without replacing the direct composite restorations (Table 1). Four (12.9%) of these teeth were treated with polyethylene fibre posts and three (9.7%) were treated with zirconia-rich glass fibre posts. The need for retreatment was determined using clinical criteria such as sensitivity to percussion and palpation, and soft, slightly tender swelling around the tooth apices.

| Time (mo) | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Materials | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | |

| Periapical lesion | A | 31 (100) | 30 (96.8) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) | 22 (71.0) | 23 (74.2) | 22 (71.0) | 23 (74.2) |

| B | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | |

| C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Time (mo) | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Materials | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | |

| Marginal leakage | A | 28 (90.3) | 29 (93.5) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) | 26 (83.9) | 25 (80.6) | 26 (83.9) | 23 (74.2) |

| B | 3 (9.7) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 5 (16.1) | 6 (19.4) | 5 (16.1) | 8 (25.8) | |

| C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Time (mo) | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Materials | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | |

| Surface staining | A | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 29 (93.5) | 28 (90.3) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) | 26 (83.9) | 26 (83.9) |

| B | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (6.5) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.1) | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Time (mo) | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Materials | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | |

| Loss of retention | A | 29 (93.5) | 30 (96.8) | 27 (87.1) | 28 (90.3) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) | 27 (87.1) |

| B | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | |

| C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

| Time (mo) | 6 | 12 | 24 | 36 | |||||

| Materials | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | Polyethylene | Zirconia | |

| Colour stability | A | 31 (100) | 31 (100) | 28 (90.3) | 29 (93.5) | 27 (87.1) | 28 (90.3) | 26 (83.9) | 27 (87.1) |

| B | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.1) | 4 (12.9) | |

| C | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| NS | NS | NS | NS | ||||||

Slight marginal staining was found on 16.1% (5/31) of teeth with polyethylene fibre posts and 25.8% (8/31) of teeth with zirconia-rich glass fibre posts (Table 2). No carious lesions were present at the restoration margins (Figure 7). Surface staining was present on 16.1% (5/31) of teeth in both groups after 36 mo (Table 3). This staining was readily removed by polishing.

After 36 mo, four teeth (12.9%) in each group showed a partial loss of restoration, manifested as “chipping” of the restoration (Figure 7). The restorations restored on every appointment were repaired. No tooth in the study sample exhibited a complete loss of restoration (Table 4). The restoration losses did not share many common features; some chipping was observed in two patients with edge-to-edge occlusion, but other similarities were absent.

After 36 mo, five teeth (16.1%) treated with polyethylene fibre posts and four teeth (12.9%) treated with zirconia-rich glass fibre posts showed slight discolouration that did not require restoration replacement (Table 5). Root fracture and post debonding were not observed during the follow-up period. No significant difference was found between post types in the five criteria evaluated at 6, 12, 24, or 36 mo (P > 0.05).

Many dentists use minimally invasive dentistry to avoid inserting posts in endodontically treated teeth[15]. The use of posts, requires the removal of tooth structure, which may increase the risk of root fracture and tooth discoloration. However, posts can be necessary to retain large resin composite restorations[9] when it is not possible to provide minimally invasive dental procedures[15], and whitening treatments or veneers can be used if a tooth becomes discolored.

A post does not benefit a structurally sound anterior tooth, and increases the chances of a non-restorable failure[19]. The same risks apply to anterior teeth with porcelain veneers[20]. A post is often indicated when an endodontically treated anterior tooth is to receive a crown. In most cases, the remaining coronal tooth structure is quite thin after root canal treatment and crown preparation. Anterior teeth must resist lateral and shearing forces, and the pulp chambers are too small to provide adequate retention and resistance without a post[21]. Evaluation of the need for a post is based on the amount of remaining coronal tooth substance able to retain a core build-up and support the final restoration following caries removal and endodontic treatment[9,21,22].

Retrospective clinical reports have suggested that artificial crown coverings increase the longevity of endodontically treated teeth[16]. A prospective clinical study, however, found no difference in the 3-year survival rates of endodontically treated teeth with fibre posts and either full cast coverage or adhesive direct composite reconstructions[5]. Similar survival rates for endodontically treated teeth with artificial crowns and those with adhesive coronal reconstructions have also been found in a 5-year prospective clinical study[7,23]. Thus, studies investigating the necessity of crown coverage for endodontically treated teeth have produced conflicting results[24]. Previous studies have classified the amount of remaining coronal tooth using the number of proximal contacts, number of residual coronal walls, and amount of crown loss[24-26].

The endodontically treated teeth in the present study were characterised by a degree of crown loss too great to allow restoration with a bonded resin and no post, and insufficient loss for crown coverage. The amount of remaining coronal tooth was therefore defined as partial crown loss.

Teeth restored with tooth-coloured posts have produced aesthetic outcomes superior to those of traditional post-core crown systems. Tooth-coloured posts are particularly important to achieve an optimal aesthetic appearance for incisors[1]. This consideration, and other positive findings for non-metal post systems, have led to increased patient acceptance of this restoration type. Two authors state that endodontic posts should be biomechanically similar to dentin[2,7].

There are many prospective and retrospective studies that examine fiber-post/resin restorations covered with full porcelain or metal-ceramic crowns[2,6,8,27,28].

Mannocci et al[29] compared the clinical success rate of endodontically treated premolars restored with fibre posts and direct composite to those restored with amalgam, finding the former to more effectively prevent root fractures but less effectively prevent secondary caries. Scotti et al[2] reported that 100 root-canal-treated teeth (38 anterior, 62 posterior teeth) restored with fibre posts and direct resin composite exhibited favourable clinical outcomes after 30 mo.

No differences in survival rate were found between material types in a clinical study of endodontically treated teeth restored with polyethylene fibre-reinforced post-core and complete cast crown or direct resin composite[30]. Another clinical study found no significant differences in the 3-year clinical performance of endodontically treated teeth with ceramometal crown coverage and those with direct composite resin restorations[5].

The restoration of selected endodontically treated teeth with fibre posts and resinbased composite without crown coverage is an economical, tooth-saving alternative to the less conservative crown coverage. Adhesive restorations also allow preservation of the maximum amount of sound tooth structure[5].

Previous clinical studies have recommended longer follow-up periods for future trials to validate simplified conservative approaches to the rehabilitation of endodontically treated teeth using fibre posts and direct resin composites[2,5,29,30]. This clinical study thus attempted to analyze the clinical performances of polyethylene and zirconia-rich glass fibre posts with direct resin composite restoration alone.

Direct resin composite and fiber post restorations showed successful coronal closures. The incidence of periapical lesions in the present sample was higher than that found by Fuss et al[13] (3% present but asymptomatic, 1% present and retreated), but compatible with the results of previous clinical studies[4,5,7,29].

Some marginal discolouration and “chipping” of resin material were observed in this study, at a rate similar to that found in a previous clinical study[2]. The repair of these conditions with the same type of resin composite used for initial restoration produced acceptable clinical results. Marginal staining on the enamel was successfully refurbished through polishing.

No significant difference was found between post type and the incidence of failure. Ayna et al[25] observed only one lost restoration after a 3-year follow-up period, as a result of secondary trauma. Scotti et al[2] observed no root fracture or debonding in their sample. Similarly, no root fracture or debonding was found in our study sample after 36 mo.

The wear resistance of resin composite is lesser than that of full ceramic or metal-ceramic crowns. However, direct resin composite restorations are less expensive for the patient[2,5]. However, it can be manufactured in a short time and does not require any laboratory operation and cost[2]. The restoration of selected endodontically treated teeth with fibre posts and direct resin composite may therefore be considered a tooth-saving alternative to the less conservative crown coverage[2,5]. Fiber post/direct resin composite restorations can be repaired, tooth structure is saved and restorations are produced at a lower cost[2].

Polyethylene fibre posts create a composite-dentin-post-core monoblock by spreading into dentin and composite resin in both the root canal and the crown part, owing to the mesh structure. Since the zircon-rich glass fibre posts are conical, they are in contact with the surface of the composite resin. It may be considered that this may adversely affect long-term clinical success. However, the results of our study showed that both administrations were equally successful in the 36-mo clinical follow-up. Composite-zircon-dentin-post-core monoblock are clinically successful as polyethylene fiber posts.

In summary, the efficacy of resin composite restorations, retained with either polyethylene or zirconia-rich glass fiber posts were similar, suggesting that both types of fiber post can be used successfully to help retain resin composite restorations.

Zircon and fiber posts are preferred to metal posts with esthetic and economic disadvantages. Metal posts are long term unsuccessful because it is mechanically bonded to root dentin. Esthetic posts are long-term successful by bonding dentine adhesives.

Long term clinical survival of esthetic posts remains controversial. Also zircon and polyethylene fiber posts with composite restorations are not often preferred. If there has been excessive crown damage it is good alternative.

Clinical survival of both posts is the same, indicating the importance of adhesive bonding. Future research should aim at increasing the adhesive bonding.

Esthetic post and core was stated to the anterior teeth with endodontic treatment. Then, it was restored by composite restorations. Clinical survival of both esthetic posts were evaluated in 36 mo periods.

Clinical survival of both posts is the same. There were no statistically different between post systems.

Esthetic post systems were successful the long-term clinical survival. It should preferred to metal posts. Direct composite restorations can preferred to the ceramic restorations. This materials provide esthetic, functional and economic advantages.

Future research should focus on comparing composite to ceramic restorations. Also such as ceramic, hybrid ceramic and peek materials were added in the research.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Turkey

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Eskitaşçioğlu M, Özalp N, Zortuk M S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li RF

| 1. | Murali Mohan S, Mahesh Gowda E, Shashidhar MP. Clinical evaluation of the fiber post and direct composite resin restoration for fixed single crowns on endodontically treated teeth. Med J Armed Forces India. 2015;71:259-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Scotti N, Eruli C, Comba A, Paolino DS, Alovisi M, Pasqualini D, Berutti E. Longevity of class 2 direct restorations in root-filled teeth: A retrospective clinical study. J Dent. 2015;43:499-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kimmel SS. Restoration and reinforcement of endodontically treated teeth with a polyethylene ribbon and prefabricated fiberglass post. Gen Dent. 2000;48:700-706. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Sarkis-Onofre R, Jacinto RC, Boscato N, Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T. Cast metal vs. glass fibre posts: a randomized controlled trial with up to 3 years of follow up. J Dent. 2014;42:582-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mannocci F, Bertelli E, Sherriff M, Watson TF, Pitt Ford TR. Three-year clinical comparison of survival of endodontically treated teeth restored with either full cast coverage or with direct composite restoration. 2002. Int Endod J. 2009;42:401-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Turker SB, Alkumru HN, Evren B. Prospective clinical trial of polyethylene fiber ribbon-reinforced, resin composite post-core buildup restorations. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:55-56. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Creugers NH, Mentink AG, Fokkinga WA, Kreulen CM. 5-year follow-up of a prospective clinical study on various types of core restorations. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:34-39. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Monticelli F, Grandini S, Goracci C, Ferrari M. Clinical behavior of translucent-fiber posts: a 2-year prospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2003;16:593-596. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Cheung W. A review of the management of endodontically treated teeth. Post, core and the final restoration. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:611-619. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Newman MP, Yaman P, Dennison J, Rafter M, Billy E. Fracture resistance of endodontically treated teeth restored with composite posts. J Prosthet Dent. 2003;89:360-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tunjan R, Rosentritt M, Sterzenbach G, Happe A, Frankenberger R, Seemann R, Naumann M. Are endodontically treated incisors reliable abutments for zirconia-based fixed partial dentures in the esthetic zone? J Endod. 2012;38:519-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Martínez-Insua A, da Silva L, Rilo B, Santana U. Comparison of the fracture resistances of pulpless teeth restored with a cast post and core or carbon-fiber post with a composite core. J Prosthet Dent. 1998;80:527-532. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fuss Z, Lustig J, Katz A, Tamse A. An evaluation of endodontically treated vertical root fractured teeth: impact of operative procedures. J Endod. 2001;27:46-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Paul SJ, Schärer P. Post and core reconstruction for fixed prosthodontic restoration. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997;9:513-20; quiz 522. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Guldener KA, Lanzrein CL, Siegrist Guldener BE, Lang NP, Ramseier CA, Salvi GE. Long-term Clinical Outcomes of Endodontically Treated Teeth Restored with or without Fiber Post-retained Single-unit Restorations. J Endod. 2017;43:188-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aquilino SA, Caplan DJ. Relationship between crown placement and the survival of endodontically treated teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2002;87:256-263. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Paul SJ, Werder P. Clinical success of zirconium oxide posts with resin composite or glass-ceramic cores in endodontically treated teeth: a 4-year retrospective study. Int J Prosthodont. 2004;17:524-528. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Freedman G. A look at posts and cores. Dent Today. 2002;21:118-125. |

| 19. | Heydecke G, Butz F, Strub JR. Fracture strength and survival rate of endodontically treated maxillary incisors with approximal cavities after restoration with different post and core systems: an in-vitro study. J Dent. 2001;29:427-433. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Baratieri LN, De Andrada MA, Arcari GM, Ritter AV. Influence of post placement in the fracture resistance of endodontically treated incisors veneered with direct composite. J Prosthet Dent. 2000;84:180-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Schwartz RS, Robbins JW. Post placement and restoration of endodontically treated teeth: a literature review. J Endod. 2004;30:289-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 505] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dammaschke T, Steven D, Kaup M, Ott KH. Long-term survival of root-canal-treated teeth: a retrospective study over 10 years. J Endod. 2003;29:638-643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Creugers NH, Kreulen CM, Fokkinga WA, Mentink AG. A 5-year prospective clinical study on core restorations without covering crowns. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18:40-41. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Fokkinga WA, Kreulen CM, Bronkhorst EM, Creugers NH. Composite resin core-crown reconstructions: an up to 17-year follow-up of a controlled clinical trial. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21:109-115. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Ayna B, Celenk S, Atakul F, Uysal E. Three-year clinical evaluation of endodontically treated anterior teeth restored with a polyethylene fibre-reinforced composite. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:136-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bitter K, Noetzel J, Stamm O, Vaudt J, Meyer-Lueckel H, Neumann K, Kielbassa AM. Randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of post placement on failure rate of postendodontic restorations: preliminary results of a mean period of 32 months. J Endod. 2009;35:1477-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Nothdurft FP, Pospiech PR. Clinical evaluation of pulpless teeth restored with conventionally cemented zirconia posts: a pilot study. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;95:311-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Signore A, Benedicenti S, Kaitsas V, Barone M, Angiero F, Ravera G. Long-term survival of endodontically treated, maxillary anterior teeth restored with either tapered or parallel-sided glass-fiber posts and full-ceramic crown coverage. J Dent. 2009;37:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mannocci F, Qualtrough AJ, Worthington HV, Watson TF, Pitt Ford TR. Randomized clinical comparison of endodontically treated teeth restored with amalgam or with fiber posts and resin composite: five-year results. Oper Dent. 2005;30:9-15. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Piovesan EM, Demarco FF, Cenci MS, Pereira-Cenci T. Survival rates of endodontically treated teeth restored with fiber-reinforced custom posts and cores: a 97-month study. Int J Prosthodont. 2007;20:633-639. [PubMed] |