Published online Dec 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1164

Peer-review started: September 29, 2018

First decision: October 18, 2018

Revised: November 7, 2018

Accepted: November 7, 2018

Article in press: November 7, 2018

Published online: December 26, 2018

Processing time: 86 Days and 18.2 Hours

Rapidly progressive pneumoconiosis (RPP) occasionally occurs in coal workers, particularly those with high exposure to silica. Here, we report the case of a 64-year-old male miller with RPP.

The patient had a persistent cough for one month and had been clinically diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis in 2011. He worked in a stone processing factory from the ages of 20 through 37 and has owned his own mill for the past 25 years. His chest radiograph showed significant increases in the size and number of lung nodules since his last follow-up in 2013. By percutaneous needle lung biopsy, the nodular lesions showed diffuse infiltration of phagocytic macrophages and birefringent crystals by polarizing microscopy. He was finally diagnosed with RPP of mixed dust pneumoconiosis combined with silicosis.

In this case, mixed dust pneumoconiosis with silicosis might be accelerated by persistent exposure to grain dust from working in a mill environment.

Core tip: Silicosis progresses slowly over a period of more than a decade and can occur after silica exposure has ceased. Pneumoconiosis including silicosis occasionally shows rapid imaging progression, and the risk factors for its progression are well defined. This case report describes the association of rapid progression pneumoconiosis with grain dust exposure. In this case, silicosis rapidly developed upon exposure to a small amount of silica mixed with other dust even long after ending excessive silica exposure. Thus, it is important to carefully study a patient’s history and consider pneumoconiosis.

- Citation: Yoon HY, Kim Y, Park HS, Kang CW, Ryu YJ. Combined silicosis and mixed dust pneumoconiosis with rapid progression: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(16): 1164-1168

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i16/1164.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i16.1164

Silicosis is a fibrotic lung disease resulting from inhalation of free crystalline silica. Silicosis is a possible risk when handling stones and sand during mining, tunneling, excavating, in foundries, and when working with abrasives and ceramics[1]. Silicosis can progress even after exposure to silica ends, and its radiologic progression takes more than a decade[2].

Rapidly progressive pneumoconiosis (RPP) is defined as an increase in small opacity profusion, a score greater than one on the International Labor Office classification, and/or development of progressive massive fibrosis in less than five years[3,4]. However, the mechanism of RPP is not fully understood. Here, we report a case of a 64-year-old male who worked in a gristmill and developed RPP long after his exposure to silica ended. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Ewha Womans University Hospital (ECT 2018-05-020-002).

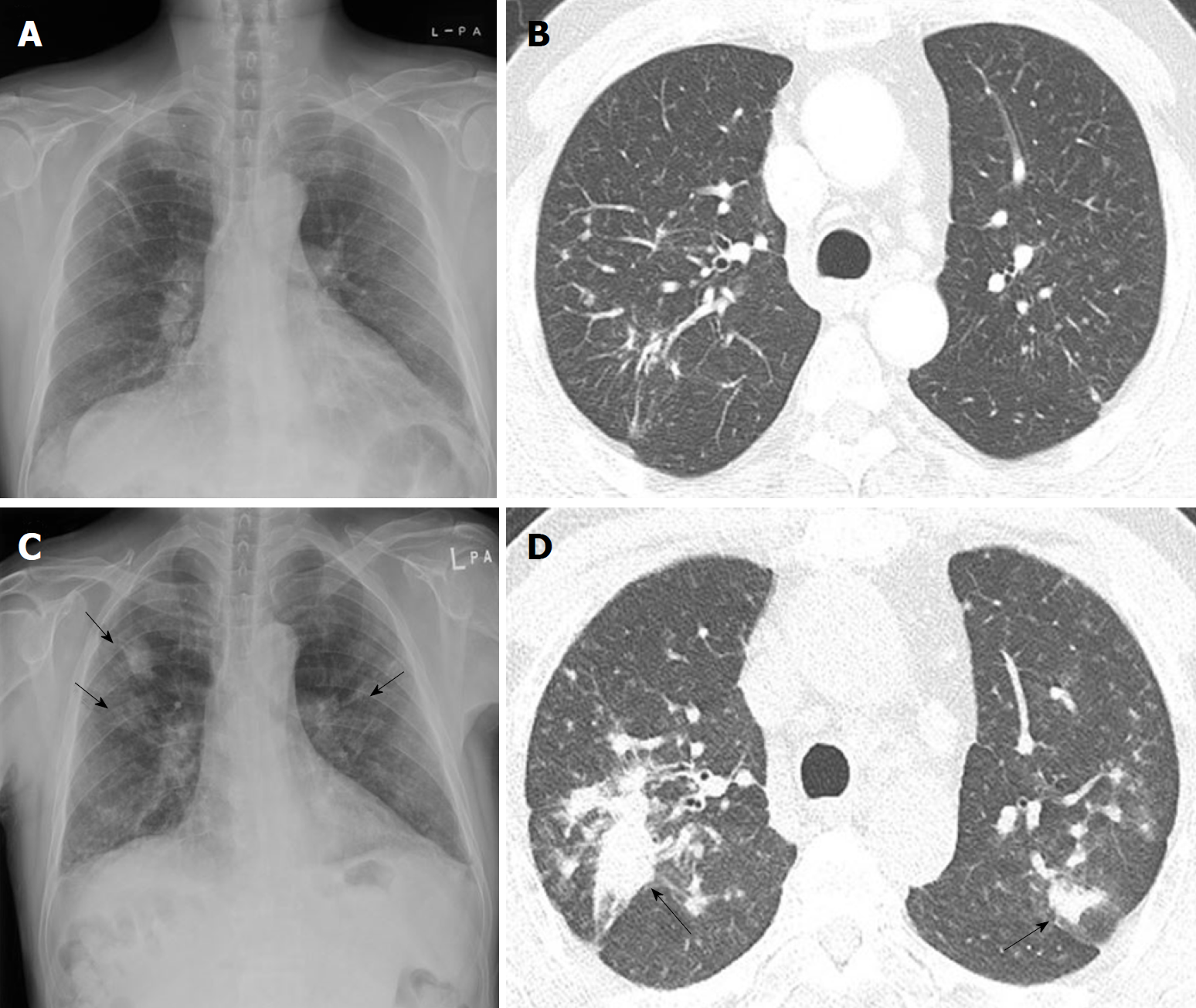

A 64-year-old male visited our institute in February 2018 for a cough productive of purulent sputum for one month. He had smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily for 30 years but had stopped 12 years previously. He was clinically diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis in 2011 based on radiologic findings in the upper lobes of both lungs with multiple small dominant lung nodules (Figures 1A and B). After completing six months of anti-tuberculosis treatment, he did not visit our clinic again due to improved respiratory symptoms. He had been working in a gristmill for 25 years.

His current physical examination was unremarkable, and there were no abnormal sounds in either lung field. In sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids at admission, tests for acid-fast bacilli and pyogenic cultures were negative. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-polymerase chain reaction and Xpert® MTB/RIF also did not detect tuberculosis in the specimens. His pulmonary function tests revealed a mild obstructive pattern [forced expiratory volume in 1 (FEV1): 75% predicted, FEV1 to forced vital capacity ratio: 0.66] with a positive bronchodilator response (ΔFEV1: 310 mL). On chest radiograph and computed tomography scans in 2018, the size and number of lung nodules significantly increased compared with those from 2011, mainly in both upper lobes (Figures 1C and D). The patient was hospitalized for percutaneous needle lung biopsy to differentiate between cancer and connective tissue disease. The patient’s occupational history was investigated. He had worked in a stone processing factory for 17 yr between 1972 and 1992, except for three years of military service. He processed granite for 12 h a day, six days a week without protective equipment in a poorly ventilated tent. After he quit working in the stone processing factory in 1992, he operated his own gristmill and worked seven days a week grinding rice, beans, red beans, and peppers using a granite roller grinder in a poorly ventilated underground mall without protective equipment for 25 years. His gristmill was in a poorly-ventilated small room located underground. He poured the grains directly into the funnel-shaped grinder entrance, and then put the grained grains into the bag by connecting the grinder outlet.

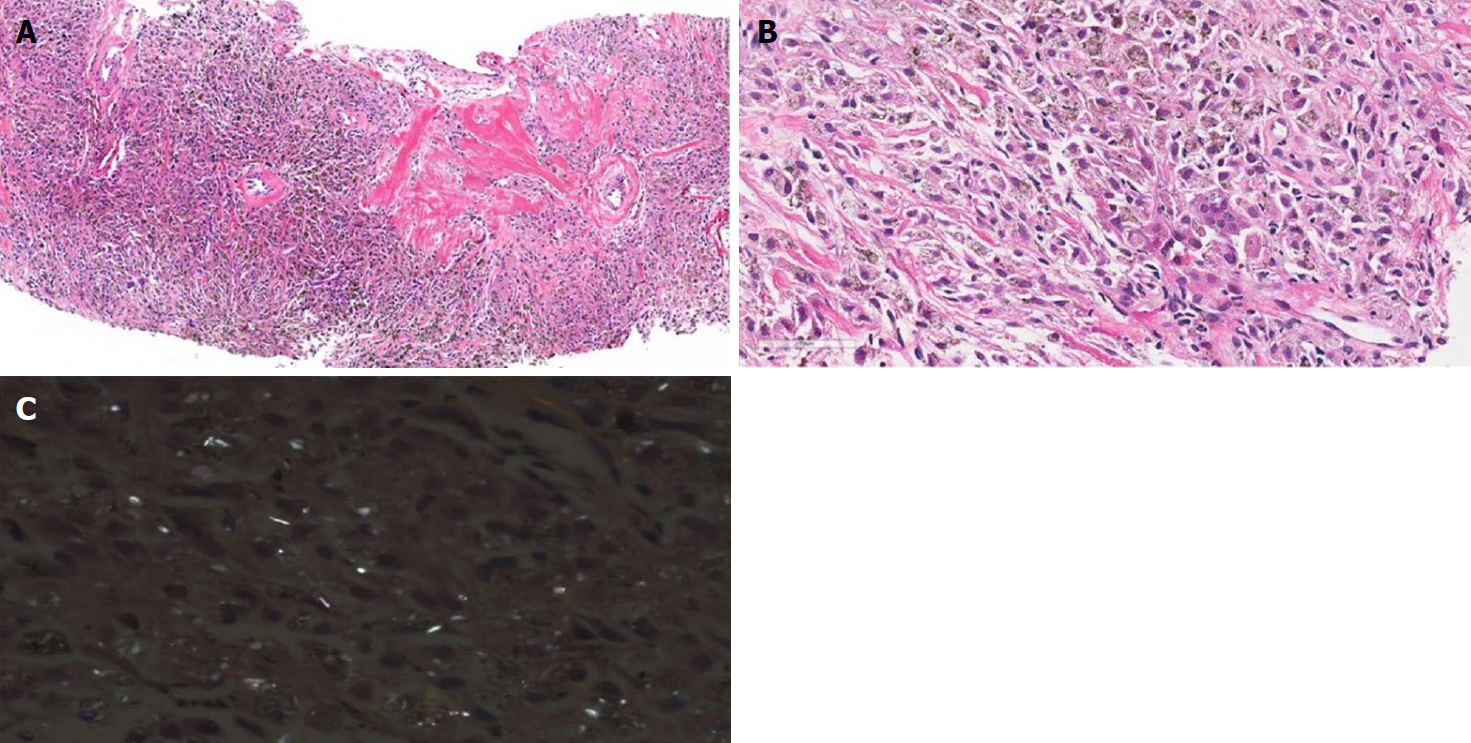

Histopathologic examination of the lung specimen showed diffuse infiltration of phagocytic macrophages with focal sclerosis (Figure 2A) and a few multi-nucleated giant cells (Figure 2B). Macrophages contained anthracotic pigment (Figure 2B), and lightly birefringent crystals were observed with polarized light microscopy (Figure 2C). Without detailed knowledge of the patient’s history, the initial histopathologic diagnosis was silicosis with rapid progression.

After consideration of the patient’s occupational history of chronic exposure to silica and cellular proliferation in histopathology, the final diagnosis was mixed dust pneumoconiosis with rapid progression. We suggest that the silica-containing grain dusts in the gristmill environment may have caused rapid progression of pneumoconiosis over five years and provoked the development of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The patient was advised to take time off from his job. He was prescribed a long-acting muscarinic antagonist plus a long-acting beta-agonist and was informed about vaccination schedules for COPD.

After one month off work and inhaler use, his respiratory symptoms resolved, and his FEV1 improved from 75% predicted to 83% predicted.

Although RPP is relatively common in coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP)[3], it is not well known in other conditions. Recently, RPP was reported in a piping worker whose pathology was consistent with silicosis and was different from that of CWP because it showed silicotic nodules and birefringent particles by polarized light microscopy[5]. In our case, RPP developed in a mill worker who had previously worked in a stone processing factory but had received no silica exposure for 25 years.

Crystalline silica is a toxic substance that promotes inflammation and leads to lung fibrosis even after discontinued exposure[6]. Cohen et al. reported that RPP was associated with exposure to silica[4]. However, the present case is the first to report RPP after an extended period of discontinuation of silica exposure. The pathogenesis of RPP remains unclear, and excessive exposure to grain dust may be associated with RPP in the present case.

There are several reports that exposure to grain dust is associated with pneumoconiosis[7,8]. Sundaram et al. proposed the term “flour mill lung” for two cases of mixed dust fibrosis in flour millers who had worked in poorly ventilated flour mills for more than 20 years and were grinding wheat with a stone grinder that contained more than 80 percent silica[7]. They suggested that small amounts of silica might contribute to mixed dust fibrosis with organic and inorganic dust. Grain dust itself contains various contaminants, including crystalline silica[9]. In the present case, continued exposure to excessive grain dust containing small amounts of silica may have led to RPP, even though the main exposure to silica (stone processing) had been discontinued long ago. In this case, silica, which is weakly birefringent under the usual polarized light, was identified in a lung biopsy specimen, and silicosis was first considered in histopathologic diagnosis. However, the lung lesions in our case were highly cellular rather than fibrotic. In silicosis, cellular proliferation is usually seen in the acute stage after heavy exposure to silica, and the lesion is replaced by fibrosis and ischemic changes in the chronic stage[10]. Since cellular infiltration occurred long after cessation of stone processing, contaminated grain dust during recent gristmill work may have played a role in the rapid progression of this case. Mixed dust pneumoconiosis refers to the changes caused by inhalation of a mixture of silica (less than 10% in proportion) and other less fibrogenic substances. Surgically resected specimens typically show a stellate margin in histologic section[10]. Although discrimination between silicosis and mixed dust pneumoconiosis was not possible with needle biopsy specimen only, we concluded that the presenting case was rapidly progressing mixed (grain) dust pneumoconiosis after comprehensive correlation of occupational history and pathologic features.

Because pneumoconiosis mostly exhibits its clinical signs or imaging features long after the exposure occurs, it is necessary to study the total history of the patient, particularly for occupational and environmental exposures. Every physician should be aware of this occupational disease to arrive at an accurate diagnosis.

(1) This case report describes the association of rapid progression pneumoconiosis with grain dust exposure; (2) Even long after the end of excessive silica exposure, silicosis can develop; and (3) It is important to suspect pneumoconiosis and to carefully study patient history.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Banks DE, Deng B, Nacak M S- Editor: Wang JL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Murray JF, Nadel JA, Broaddus VC, Mason RJ, Ernst JD, King Jr TE, Lazarus SC, Slutsky AS, Gotway MB. Preface to the Sixth Edition. Murray & Nadel’s Textbook of Respiratory Medicine, 2-Volume Set. 6th eds. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders 2016; 1310-1314. |

| 2. | Dumavibhat N, Matsui T, Hoshino E, Rattanasiri S, Muntham D, Hirota R, Eitoku M, Imanaka M, Muzembo BA, Ngatu NR. Radiographic progression of silicosis among Japanese tunnel workers in Kochi. J Occup Health. 2013;55:142-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Antao VC, Petsonk EL, Sokolow LZ, Wolfe AL, Pinheiro GA, Hale JM, Attfield MD. Rapidly progressive coal workers’ pneumoconiosis in the United States: geographic clustering and other factors. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62:670-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cohen RA, Petsonk EL, Rose C, Young B, Regier M, Najmuddin A, Abraham JL, Churg A, Green FH. Lung Pathology in U.S. Coal Workers with Rapidly Progressive Pneumoconiosis Implicates Silica and Silicates. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193:673-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Tsuchiya K, Toyoshima M, Akiyama N, Kono M, Nakamura Y, Funai K, Baba S, Sugimura H, Kanayama H, Suda T. Rapid Radiologic Progression of Silicosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:e39-e42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rabolli V, Lo Re S, Uwambayinema F, Yakoub Y, Lison D, Huaux F. Lung fibrosis induced by crystalline silica particles is uncoupled from lung inflammation in NMRI mice. Toxicol Lett. 2011;203:127-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sundaram P, Kamat R, Joshi JM. Flour mill lung: a pneumoconiosis of mixed aetiology. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2002;44:199-201. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Palmer PE, Daynes G. Transkei silicosis. S Afr Med J. 1967;41:1182-1188. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Spankie S, Cherrie JW. Exposure to grain dust in Great Britain. Ann Occup Hyg. 2012;56:25-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Corrin B, Nicholson AG. Chapter 7 - Occupational, environmental and iatrogenic lung disease. Pathology of the Lungs. 3rd eds. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone 2011; 327-399. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |