Published online Dec 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i15.1012

Peer-review started: August 22, 2018

First decision: October 5, 2018

Revised: November 13, 2018

Accepted: November 14, 2018

Article in press: November 15, 2018

Published online: December 6, 2018

Processing time: 107 Days and 6.6 Hours

A 52-year-old woman was admitted with hypovolemic shock. Emergency endoscopy revealed three hemorrhagic duodenal ulcers (all stage A1) with exposed vessels. Two ulcers were successfully treated by endoscopic clipping; however, the remaining ulcer on the posterior wall of the horizontal portion of the duodenum could not be clipped. Because her vital signs were rapidly worsening, we performed transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) as it is less invasive than surgery. Computed tomography aortography showed that the duodenal hemorrhage was sourced from the lower branch of the right renal artery. In general, the duodenum is fed by branches from the gastroduodenal artery or superior mesenteric artery. However, this patient had three right renal arteries. The lower branch of the right renal artery at the L3 vertebral level was at the same level as the horizontal portion of the duodenum. Complete hemostasis was achieved by TAE using metallic coils and n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. After TAE, she recovered from the hypovolemic shock and was discharged from hospital. She has had no recurrence of the hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer for over 1 yr, and follow-up endoscopy showed no necrosis or stricture of the duodenum. Although she developed a small infarct of her right kidney, her renal function was satisfactory. In summary, the present case is the first reported case of hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer in which the culprit vessel was a renal artery that was successfully treated by TAE. Computed tomography aortography before TAE provides valuable information regarding the source of a duodenal hemorrhage.

Core tip: We report a rare case of a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer fed by a renal artery that was successfully treated by transcatheter arterial embolization. Generally, the duodenum is fed by branches from the gastroduodenal artery or superior mesenteric artery. However, this patient had three right renal arteries, and the hemorrhage was fed by the lower branch of the right renal artery. This branch was located at the L3 vertebral level, at the same level as the horizontal portion of the duodenum. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case in which a renal artery fed a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer.

- Citation: Anami S, Minamiguchi H, Shibata N, Koyama T, Sato H, Ikoma A, Nakai M, Yamagami T, Sonomura T. Successful endovascular treatment of endoscopically unmanageable hemorrhage from a duodenal ulcer fed by a renal artery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(15): 1012-1017

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i15/1012.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i15.1012

Annually, upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding affects approximately 100 per 100000 people internationally[1,2]. Endoscopic clipping is the first-line technique to achieve hemostasis. If hemostasis is difficult to achieve using this technique, then second-line treatments include transcatheter arterial embolization (TAE) and surgery[3]. A meta-analysis revealed that recurrent bleeding was more frequent after TAE than after surgery, but TAE is necessary for inoperable or elderly patients because it is less invasive and results in a shorter hospital stay[3,4,5]. TAE involves embolization of the artery responsible for bleeding (typically branches of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) or superior mesenteric artery). In the present case, we identified the right renal artery as the vessel responsible for a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer that was difficult to treat endoscopically. We report on this extremely rare case.

The patient was a 52-year-old woman. She had a history of recurrent duodenal ulcers caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. In addition, she suffered the sudden death of a close relative in a traffic accident. She was subsequently unable to eat for several days and began experiencing melena and epigastric pain. She was examined for a consciousness disorder by a local physician, who also noted hematemesis in the patient. On arrival, the patient exhibited impaired consciousness. Her systolic blood pressure was 63 mmHg, pulse rate was 130 bpm, and SpO2 was 100% in room air. The results of blood tests (Table 1) indicated anemia, so a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer was suspected. She was admitted to the emergency room of our hospital to undergo therapeutic upper GI endoscopy.

| Parameter | Value |

| WBC count (/μL) | 10290 |

| RBC count (104/μL) | 219 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 6.8 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 21.1 |

| Platelet (103/μL) | 23.4 |

| PT (/s) | 15.3 |

| PT (ratio %) | 76 |

| PT INR | 1.19 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 204 |

| FDP (μg/mL) | 2.4 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | < 0.3 |

| Antithrombin (%) | 63 |

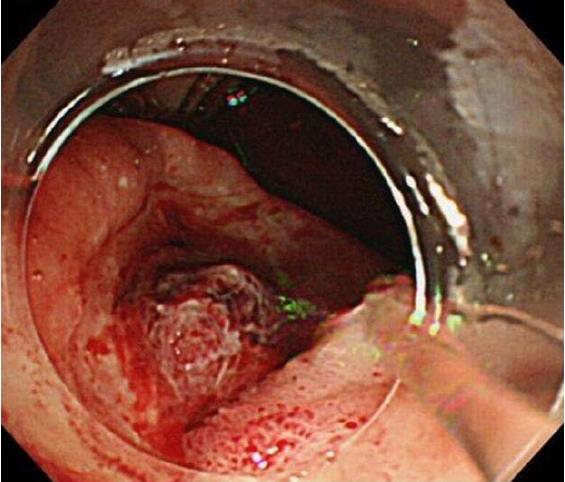

While performing a fluid infusion and blood transfusion, we conducted emergency upper GI endoscopy (GIF-Q260J; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The results indicated three hemorrhagic ulcers (all stage A1) with exposed vessels, located along the descending to horizontal portions of the duodenum (Figure 1). Two of the ulcers were successfully treated by endoscopic clipping; however, the remaining ulcer on the most anal side, on the posterior wall of the horizontal portion of the duodenum, could not be clipped. Because her vital signs were rapidly declining, we decided to perform TAE, which is less invasive than surgical treatment. Preoperative contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) was not done because her vital signs were too poor.

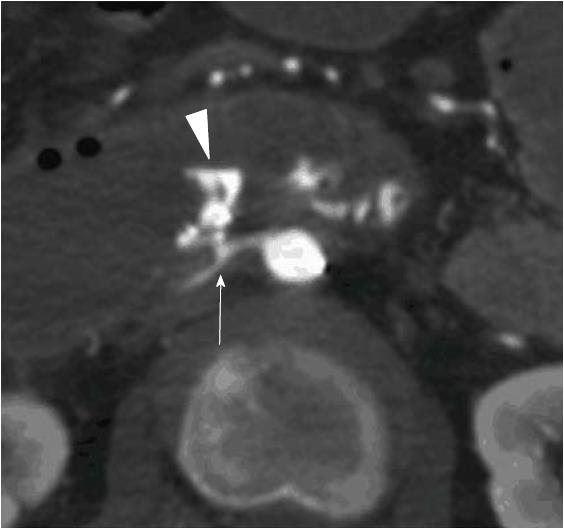

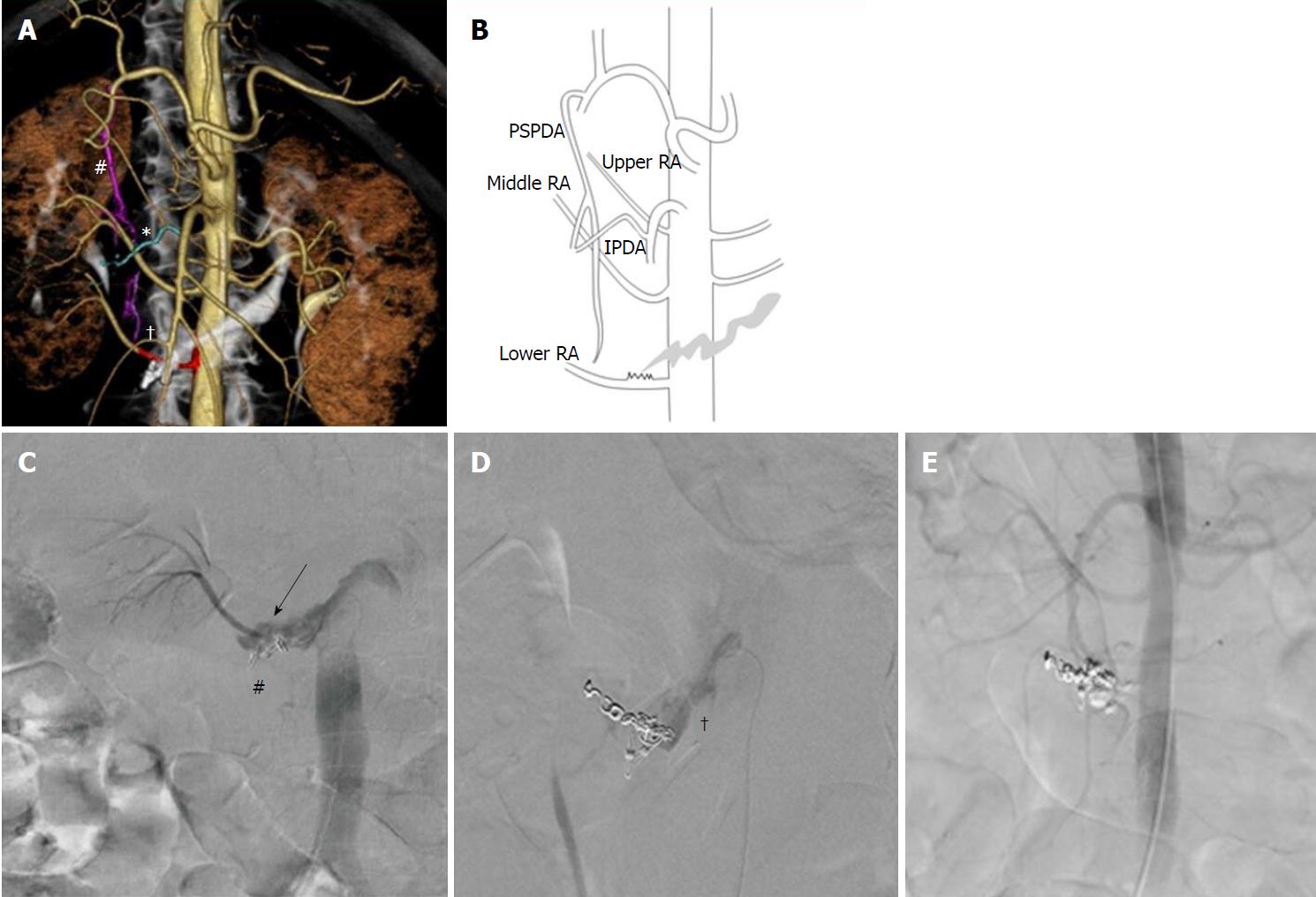

No clear signs of extravasation were seen on initial aortography or on selective angiography of the GDA and superior mesenteric artery. We then used interventional radiology-CT to perform CT during aortography[6] to identify the culprit artery. Extravasation was detected close to the clipping. Therefore, we repeated the selective angiography of the posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries, which run adjacent to this site. No clear extravasation was observed. Closer examination of the first set of CT images revealed that of the three right renal artery branches, the lower branch was near the posterior side of the hemorrhage. Thus, we performed selective angiography of this artery, which finally confirmed the source of extravasation (Figures 2, 3A, 3B, and 3C).

Because the right renal artery has three branches, and the patient’s renal function was good, we first embolized the lower branch of the right renal artery using coils (two 2-mm-diameter, 4-cm-long Tornado coils and eight 2-mm-diameter, 3-cm-long Tornado coils; Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, United States), from the distal to proximal sides of the hemorrhage site. As the distance from the origin of the renal artery to the hemorrhage site was only 7 mm, and the hemorrhagic site appeared to be widening gradually, we added no more coils due to the high risk of coil migration into the aorta and duodenum (Figure 3D). Thereafter, we used n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (NBCA) glue (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany) as the embolic material. We injected a total of 2 mL of 33% NBCA mixed with Lipiodol via three separate injections (0.5 mL, 0.5 mL, and 1.0 mL). Finally, we achieved complete hemostasis (Figure 3E).

The patient subsequently recovered from her state of shock and was transferred to the intensive care unit. The patient had no recurrence of the hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer at the 1-year follow-up. Endoscopic examination indicated no duodenal stricture or mucosal necrosis and confirmed that the condition had improved to stage S1. Follow-up CT showed unavoidable partial infarction of the right kidney as a result of iatrogenic embolization of the culprit renal artery, but no evidence of renal dysfunction or other abnormality.

The first-line treatment for upper GI bleeding is endoscopic therapy, but when such therapy is difficult to perform, endovascular treatment is an eligible alternative[7-14]. In the present case, endovascular treatment was selected because of the potential difficulty of endoscopic therapy and the patient’s state of shock.

In general, the arteries feeding the duodenum are the supraduodenal artery and the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which branch from the GDA and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, which branches from the superior mesenteric artery[15]. Thus, the culprit artery in cases of hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer is usually one of these three arteries depending on the site of bleeding[9]. Toyoda et al[7] reported five patients with duodenal ulcer hemorrhage who underwent prophylactic embolization of the GDA, posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, and anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery using TAE because angiography failed to identify any extravasation. Of these, four patients had no recurrence of bleeding during the observation period; however, the remaining patient died, indicating that in this case, an atypical culprit artery could not be ruled out, as in the present case.

Anatomically, the descending and ascending portions of the duodenum are positioned at the level of the second lumbar vertebra (L2), and the horizontal portion is at the L3 level, whereas the bilateral renal arteries are located at the level of L1–L2, according to previous angiographic studies[15,16]. Thus, in the vast majority of cases, when a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer occurs in the horizontal portion of the duodenum, the relative positions of the structures preclude a renal artery from being the culprit artery. In the present case, the position of the duodenum was normal, but the branches of the renal artery were anomalous, with three located on the right. As the lower branch of the right renal artery branched at the L3 level, we suspected it to be the culprit artery. This branching pattern is extremely rare, occurring in less than 1% of all cases[16].

In the present patient, we observed no ischemic changes or necrosis in the duodenal mucosa and no stricture during the postoperative observation period; however, there was partial infarction of the right kidney. The most concerning complications observed after TAE performed for GI bleeding generally include ischemia of the GI tract, stricture, and necrosis. The therapeutic outcomes and complication rates differ depending on the embolic materials used. Lang et al[11] reported that when performing distal embolization, NBCA was associated with better long-term hemostasis than was gelatin sponge or polyvinyl alcohol. Yonemitsu et al[17] reported that while gelatin sponge potentially increases the risk of recurrent bleeding, especially in patients with coagulopathic conditions, the use of NBCA led to satisfactory hemostasis. In addition, TAE using NBCA for upper and lower GI tract bleeding resulted in hemostasis in almost all cases, and no patients suffered GI tract necrosis[18,19]. In another study, hemostasis was achieved in all TAE procedures with NBCA for diverticular hemorrhage of the ascending portion of the duodenum, and although the adverse effects included ulceration occupying half of the duodenal circumference, no strictures or necrosis developed[20]. Nevertheless, an extremely high risk of GI tract necrosis has been reported when using NBCA for embolization of five or more vasa recta with TAE in the lower GI tract[21]. Thus, when utilizing NBCA, careful consideration of the extent of embolization is required. In the present case, no GI mucosal damage was observed during the postoperative observation period, and the only complication observed was partial renal infarction. Thus, the culprit artery (the lower branch of the right renal artery) was not a duodenal feeder, but rather ran along the horizontal portion of the duodenum due to the anomaly. As a result, the artery adhered to the serosa due to the inflammation caused by recurrent ulceration in the horizontal portion of the duodenum. We believe that the area of adhesion eventually penetrated the duodenum.

In summary, we have reported a case of hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer in which the culprit vessel was the right renal artery. To our knowledge, there have been no other cases reported in the literature. Based on our experience of this case, we believe that performing CT aortography before TAE will provide valuable information to identify the artery responsible for the hemorrhage.

A case of hypovolemic shock with a history of recurrent duodenal ulcers.

Hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer.

Other hemorrhagic lesions.

Vital signs and blood tests on arrival showed hypovolemic shock.

Emergency endoscopy and computed tomography revealed hemorrhagic duodenal ulcers.

Not obtained.

Interventional radiology.

Based on our search of the literature, there are no other reported cases of hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer in which the culprit vessel was the right renal artery.

None.

In patients with a hemorrhagic duodenal ulcer and an anomaly of the right renal artery, the right renal artery could be the culprit vessel.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ricci G, Tomizawa M S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Jairath V, Hearnshaw S, Brunskill SJ, Doree C, Hopewell S, Hyde C, Travis S, Murphy MF. Red cell transfusion for the management of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;CD006613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB, Northfield TC. Incidence of and mortality from acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom. Steering Committee and members of the National Audit of Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage. BMJ. 1995;311:222-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 577] [Cited by in RCA: 590] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eriksson LG, Ljungdahl M, Sundbom M, Nyman R. Transcatheter arterial embolization versus surgery in the treatment of upper gastrointestinal bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1413-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kyaw M, Tse Y, Ang D, Ang TL, Lau J. Embolization versus surgery for peptic ulcer bleeding after failed endoscopic hemostasis: a meta-analysis. Endosc Int Open. 2014;2:E6-E14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ripoll C, Bañares R, Beceiro I, Menchén P, Catalina MV, Echenagusia A, Turegano F. Comparison of transcatheter arterial embolization and surgery for treatment of bleeding peptic ulcer after endoscopic treatment failure. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:447-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Minamiguchi H, Kawai N, Sato M, Ikoma A, Sanda H, Nakata K, Tanaka F, Nakai M, Sonomura T, Murotani K. Volume-rendered hemorrhage-responsible arteriogram created by 64 multidetector-row CT during aortography: utility for catheterization in transcatheter arterial embolization for acute arterial bleeding. Springerplus. 2014;3:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Toyoda H, Nakano S, Takeda I, Kumada T, Sugiyama K, Osada T, Kiriyama S, Suga T. Transcatheter arterial embolization for massive bleeding from duodenal ulcers not controlled by endoscopic hemostasis. Endoscopy. 1995;27:304-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ljungdahl M, Eriksson LG, Nyman R, Gustavsson S. Arterial embolisation in management of massive bleeding from gastric and duodenal ulcers. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:384-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | De Wispelaere JF, De Ronde T, Trigaux JP, de Cannière L, De Geeter T. Duodenal ulcer hemorrhage treated by embolization: results in 28 patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2002;65:6-11. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Loffroy R. Management of duodenal ulcer bleeding resistant to endoscopy: surgery is dead! World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1150-1151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lang EK. Transcatheter embolization in management of hemorrhage from duodenal ulcer: long-term results and complications. Radiology. 1992;182:703-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wang YL, Cheng YS, Liu LZ, He ZH, Ding KH. Emergency transcatheter arterial embolization for patients with acute massive duodenal ulcer hemorrhage. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:4765-4770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Loffroy R, Guiu B, D’Athis P, Mezzetta L, Gagnaire A, Jouve JL, Ortega-Deballon P, Cheynel N, Cercueil JP, Krausé D. Arterial embolotherapy for endoscopically unmanageable acute gastroduodenal hemorrhage: predictors of early rebleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:515-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Loffroy R, Guiu B. Role of transcatheter arterial embolization for massive bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5889-5897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stringer , MD , editor . Abdomen and Pelvis. In: Susan Standring, editor. Gray’s Anatomy 41st edition. Amsterdam, Elsevier 2016; 1046-1047, 1124-1127. |

| 16. | Ozkan U, Oğuzkurt L, Tercan F, Kizilkiliç O, Koç Z, Koca N. Renal artery origins and variations: angiographic evaluation of 855 consecutive patients. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006;12:183-186. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yonemitsu T, Kawai N, Sato M, Tanihata H, Takasaka I, Nakai M, Minamiguchi H, Sahara S, Iwasaki Y, Shima Y. Evaluation of transcatheter arterial embolization with gelatin sponge particles, microcoils, and n-butyl cyanoacrylate for acute arterial bleeding in a coagulopathic condition. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:1176-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yata S, Ihaya T, Kaminou T, Hashimoto M, Ohuchi Y, Umekita Y, Ogawa T. Transcatheter arterial embolization of acute arterial bleeding in the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:422-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Morishita H, Yamagami T, Matsumoto T, Asai S, Masui K, Sato H, Majima A, Sato O. Transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate for acute life-threatening gastroduodenal bleeding uncontrolled by endoscopic hemostasis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;24:432-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sanda H, Kawai N, Sato M, Tanaka F, Nakata K, Minamiguchi H, Nakai M, Sonomura T. Arterial supply to the bleeding diverticulum in the ascending duodenum treated by transcatheter arterial embolization- a duodenal artery branched from the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. Springerplus. 2014;3:17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ikoma A, Kawai N, Sato M, Sonomura T, Minamiguchi H, Nakai M, Takasaka I, Nakata K, Sahara S, Sawa N. Ischemic effects of transcatheter arterial embolization with N-butyl cyanoacrylate-lipiodol on the colon in a Swine model. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33:1009-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |