Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.854

Peer-review started: August 9, 2018

First decision: August 24, 2018

Revised: September 4, 2018

Accepted: October 12, 2018

Article in press: October 11, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 110 Days and 16.6 Hours

Pretibial myxedema (PTM), an uncommon manifestation of Graves’ disease (GD), is a local autoimmune reaction in the cutaneous tissue. The treatment of PTM is a clinical challenge. We herein report on a patient with PTM who achieved complete remission by multipoint subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid and topical glucocorticoid ointment application for a self-controlled study. A 53-year-old male presented with a history of GD for 3.5 years and a history of PTM for 1.5 years. Physical examination revealed slight exophthalmos, a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland, and PTM of both lower extremities. One milliliter of triamcinolone acetonide (40 mg) was mixed well with 9 mL of 2% lidocaine in a 10 mL syringe. Multipoint intralesional injections into the skin lesions of the right lower extremity were conducted with 0.5 mL of the premixed solution. A halometasone ointment was used once daily for PTM of the left lower extremity until the PTM had remitted completely. The patient’s PTM achieved complete remission in both legs after an approximately 5-mo period of therpy that included triamcinolone injections once a week for 8 wk and then once a month for 2 mo for the right lower extremity and halometasone ointment application once daily for 8 wk and then once 3-5 d for 2 mo for the left lower extremity. The total dosage of triamcinolone acetonide for the right leg was 200 mg. Our experience with this patient suggests that multipoint subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid and topical glucocorticoid ointment application are safe, effective, and convenient treatments. However, the topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment is a more convenient treatment for patients with PTM.

Core tip: Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is an extrathyroidal, dermatological manifestation of Graves’ disease. And PTM may be associated with autoimmunity. Local glucocorticoid therapy is the most common and effective option for PTM. However, any difference in efficacy between the external use of a glucocorticoid ointment and intralesional glucocorticoid is unclarified. Our experience with this patient suggests that multipoint subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid and topical glucocorticoid ointment application are safe, effective, and convenient treatments. However, the topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment is a more convenient treatment for patients with PTM.

- Citation: Zhang F, Lin XY, Chen J, Peng SQ, Shan ZY, Teng WP, Yu XH. Intralesional and topical glucocorticoids for pretibial myxedema: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 854-861

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/854.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.854

Pretibial myxedema (PTM) is an extrathyroidal, dermatological manifestation of Graves’ disease (GD). Recent research on the pathogenesis of PTM has shown that PTM may be associated with autoimmunity. The presence of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors in fibroblasts of the skin may play a major role in the pathogenesis of PTM. In general, PTM is self-limited and asymptomatic; however, advanced cases may cause cosmetic or functional problems. Local glucocorticoid therapy is the most common and effective option for PTM. However, any difference in efficacy between the external use of a glucocorticoid ointment and intralesional glucocorticoid is unclarified. Therefore, we report on a patient with PTM who underwent multipoint subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid (triamcinolone) and topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment for the two legs.

A 53-year-old man visited our clinic for fatigue, irritability, and weight loss for 3.5 years and PTM for 1.5 years. Three and a half years before, he had felt weak and had excessive sweating, palpitations, and a weight loss of 10 kg. One month later, he saw a doctor at a local hospital. His thyroid function showed a decreased TSH level and an elevated free triiodothyronine (FT3) level. His serum thyrotropin receptor antibody (TRAb) level was more than 40 IU/L (reference interval for TRAb: 0-1.75 IU/L). He was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism and prescribed methimazole 15 mg once daily. However, the patient did not take the drug regularly. One and a half years ago, swollen red areas with a diameter of about 5 cm and clear boundaries and a slightly tougher texture - but without itching - were found above both ankles. He was diagnosed at the local hospital as having PTM and prescribed halometasone 1 g twice a day and oral tripterygium. One week later, the myxedema had improved. He continued treatment for 2 wk but after discontinuing the halometasone ointment, the myxedema relapsed and was accompanied by occasional acupuncture-like pain. Later, he gave up treatment for 16 mo until he came to our hospital.

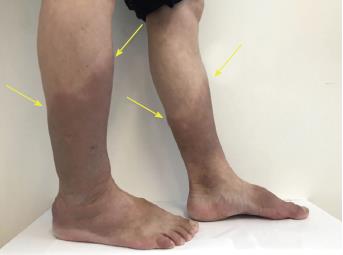

The patient presented with eyelid edema, slight exophthalmos, and a diffusely enlarged thyroid gland (grade II-III). The bilateral pretibial and ankle skin was thickened with a hard texture, uneven surface, and non-pitting edema (Figure 1).

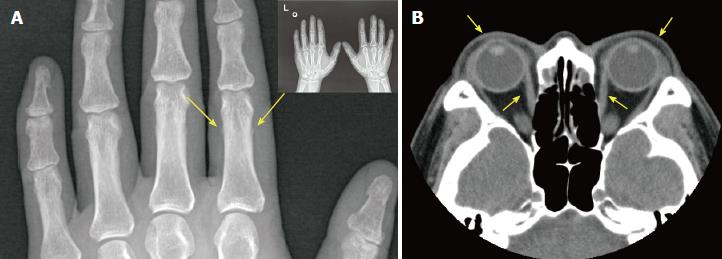

The results of thyroid function showed a decreased TSH level (0.0014 mIU/L; reference interval: 0.35-4.94 mIU/L), an increased FT3 level (7.27 pmol/L; reference interval: 2.63-5.7 pmol/L), and a normal free thyroxine (FT4) level (13.46 pmol/L; reference interval: 9.01-19.05 pmol/L). The titers of thyroglobulin antibody (TgAb), thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb), and TRAb were 1.73 IU/mL (reference interval: 0-4.11 IU/mL), 164.33 IU/mL (reference interval: 0-5.61 IU/mL) and > 40 IU/L (reference interval: 0-1.75 IU/L), respectively. A biopsy of the pretibial skin showed a large amount of deposited mucin-like substances between the collagen and the gaps among the collagenous fibers were widened. Moreover, hyperkeratosis of squamous epithelium and perivascular inflammatory cell infiltration were found (Figure 2). All of these findings supported the diagnosis of PTM.

An X-ray scan indicated a periosteal reaction in the phalangeal bone of the index finger of the left hand (Figure 3A). Finally, the patient was diagnosed as GD, exophthalmos, PTM, and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy (EMO) syndrome.

A computed tomography scan of the eye socket showed that the bilateral extraocular muscles were slightly thickened and both eyeballs were slightly extruded (Figure 3B).

Intradermal injections of triamcinolone acetonide were used for PTM of the right lower extremity. The injections were once a week for 8 wk and then once a month for 2 mo. For each treatment, 2% lidocaine was used to dilute triamcinolone acetonide. The concentration of triamcinolone acetonide was 4 mg/mL. Ten injection points were used along the upper border of the skin lesions and 0.5 mL of diluted triamcinolone was injected at each point using a 1-mL syringe. A halometasone ointment was used once a day for PTM of the left lower extremity. After the first injection series, the range of the lesions of the right leg narrowed by about 1.5–2 cm; no significant change occurred on the left leg. After the second injection series, the scope and thickness of the swelling shrunk markedly in both legs. After the third injection series, the fringe skin of the lesions became soft and thin, similar to the normal skin. With treatment, the thickness of the lesions of both lower extremities was significantly reduced and eventually returned to the same thickness as that of normal skin. The color of the skin gradually lightened. Eight weeks after the injection therapy, scabs occurred around the border of the lesion on the right leg and then fell off on their own. The new skin showed a pink color, which was not obvious on the left leg. Five months later, the swelling of both lower extremities had disappeared and the thickness of the skin had returned to normal. However, little pigmentation was present. The total dose of triamcinolone acetonide used for the right leg was 200 mg. Complete remission of PTM was achieved in both lower extremities. No side effects from the glucocorticoid were found in this patient.

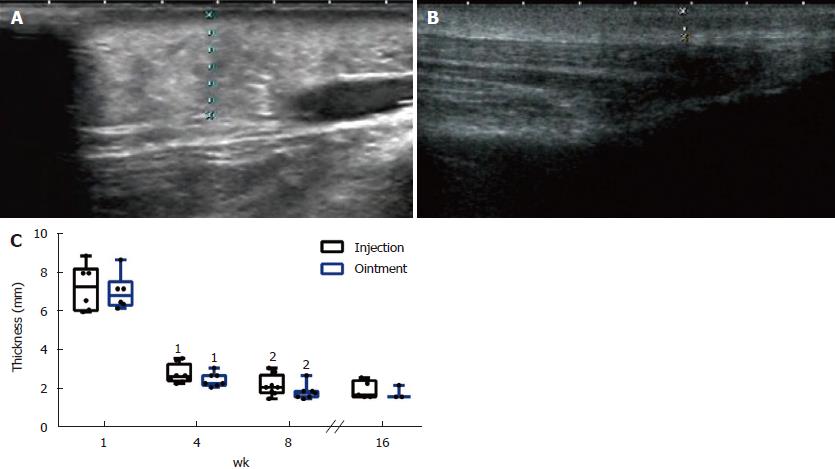

Ultrasound can be a good option for assessing PTM lesion thickness[1]. The thickened skin of this patient before the specific treatment was 7.27 ± 1.20 mm (right) and 7.03 ± 0.92 mm (left) (Figure 4A). The thickened skin of the lesions after treatment was 1.96 ± 0.46 mm (right) and 1.80 ± 0.35 mm (left) (Figure 4B). We found that compared to before treatment, the thickness of the skin lesions was significantly different after 4 wk of treatment. Significant differences were also observed in the skin thickness in both legs between 4 wk and 8 wk after treatment (Figure 4C).

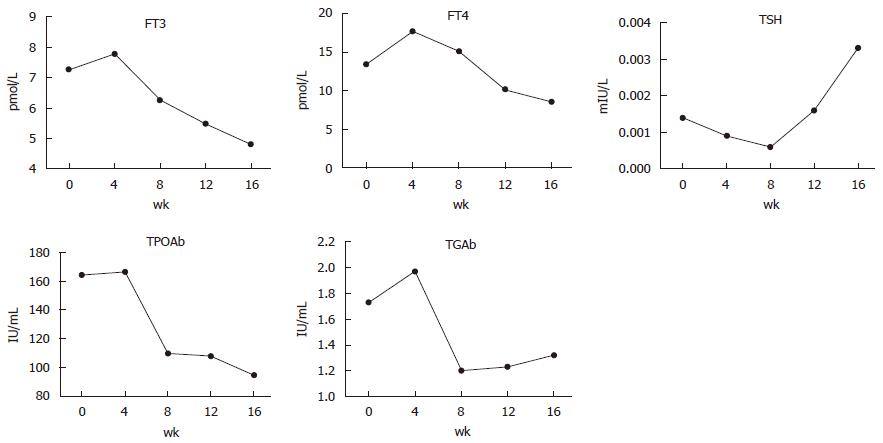

The patient had been prescribed methimazole 30 mg daily for hyperthyroidism at the beginning of the treatment for PTM. The changes in thyroid function are interesting (Figure 5). During the first month of treatment, the levels of FT3, FT4, TPOAb, and TgAb were increased and TSH was decreased. Thereafter, FT3, FT4, TPOAb, and TgAb declined while TSH levels rose gradually. However, TRAb was always greater than 40 IU/L.

Seven months after the end of treatment, we followed the patient and found that pretibial skin of both legs was not swelling and lighter in color. No recurrence of PTM was observed.

Our experience with this patient has shown that multiple subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid and topical glucocorticoid ointment application had similar efficacy for skin lesions in PTM patients with diffuse swelling and a medical history of no more than 2 years. However, the application of a glucocorticosteroid ointment was more convenient, and the patient had no obvious discomfort. These made the patient have better compliance. The patient can apply the treatment at home according to the doctor’s advice and avoid frequent entry into the hospital. Therefore, the topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment is safe and effective, and is a convenient treatment for patients with PTM.

PTM is an important autoimmune manifestation of GD. Although it is usually located in the pretibial area, it can involve the arms, back, and even the face. Therefore, it should be called localized myxedema or thyroid dermopathy. The prevalence of PTM is 1.6% in thyroid disease, 0.5%–4% in GD, and 15% in severe Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO). However, 97% of PTM patients are associated with GO[2] and 20% are associated with acropachy[3]. Myxedema can occur as a component of the triad of exophthalmos, myxedema, and osteoarthrosis (EMO syndrome), which is a rare disease and whose prevalence is < 1% in autoimmune thyroid disease[4]. The symptoms of EMO tend to occur in chronological order with the onset of eye disease followed by myxedema and then eventually osteoarthrosis or clubbing on long-term duration[5-7]. Clinically, myxedema presents as non-punctate, nodular, or plaque-like edema. In severe cases, skin disease may develop into elephantiasis. Histologically, the tissue shows extensive space between collagen bundles under hematoxylin and eosin staining and accumulation of polysaccharide acid between collagen bundles in the dermis layer under alcian blue staining. The pathogenesis of PTM is unclear but there appears to be interactions of immunologic, cellular, and mechanical processes. TSH receptors in fibroblasts can be attacked by TRAbs, inducing immune activation that is mediated by T lymphocytes[8].

Treatments for PTM include managing the risk factors and thyroid dysfunction and using specific therapy for local dermopathy. Local glucocorticoid application to PTM has been the most effective therapeutic option. Lan et al[9] have treated PTM using an intralesional glucocorticoid - triamcinolone acetonide acetate - at a concentration of 50 mg/5 mL and the total dose was no more than 100 mg at each session in a patient. Intralesional injection was once every 3 d (regimen 1) or once every 7 d (regimen 2) in PTM patients. Seven injection sessions were considered as a therapy course. Two-thirds of the patients in each regimen remitted completely at the 3.5-year follow-up. However, patients following regimen 1 presented with more adverse effects. The conclusions of this article indicate that early treatment of PTM with glucocorticoids is necessary to achieve a complete response. Dosage and frequency of the intralesional steroid injections and the lesion variants influence the efficacy of PTM. Once every seven days is a better regimen. Lan et al[10] also performed a retrospective study. An intralesional glucocorticoid was used and the dosage of triamcinolone acetonide acetate was 50 mg/5 mL. In protocol 1, glucocorticoid was used once a week and treatment was administered until the swollen lesions had disappeared. In protocol 2, glucocorticoid was used once a week for 8 wk and then once a month for 6 mo. Protocol 1 was used for patients with nodular, plaque, and diffusely swollen variants; all patients had a complete response. Protocol 2 was used for patients with an elephantiasis variant; 26.7% of the patients had a complete response and 73.3% had a partial response. The two protocols were both effective. Sendhil Kumaran et al[11] reported local glucocorticoid application for PTM with different routes of administration. In his research, a topical clobetasol propionate (0.05%) was applied twice daily under occlusion for 18 patients with plaque-type PTM and a disease duration greater than 3 years. An initial improvement in the form of reduced plaque thickness was observed in 14 patients by 6 mo. Takasu et al[12] applied a topical steroid ointment with sealing cover for PTM patients. He found that this option was effective in patients with several months of the appearance of PTM and ineffective in patients with 5-10 years of the appearance of PTM. The results from several other studies seemingly indicate that intralesional glucocorticoid is a better option. Schwartz et al[13] reported that topical subcutaneous injections were more effective than glucocorticoid-oppressive dressings. The response rate to local injections was 27.3%, which was higher than that of topical glucocorticoid daubing or compression dressings. Deng et al[14] reported that the use of intralesional corticoids had positive results with a shorter treatment time. Vannucchi et al[15] reported that treatment of PTM with dexamethazone injected subcutaneously with mesotherapy needles. One month after treatment, all patients showed improvement of PTM at clinical assessment and reduction of the thickness of the lesions at ultrasound, involving mostly the dermis. Ren et al[16] researched that whether a premixed corticosteroid, compound betamethasone, could enhance remission rate and decrease recurrence rate in patients with PTM. They considered that compound betamethasone with multipoint intralesional injection is a feasible, effective, and secure novel strategy in the treatment of PTM. However, we cannot evaluate the precise difference in the effects of local glucocorticoids among the different administration routes because of different clinical phenotypes, doses, and frequencies of glucocorticoid in the articles related to treatment for PTM[8-11,14,15,17].

As we know, higher-dose glucocorticoids can cause obvious side effects, such as hyperglycemia, hypertension, and Cushing syndrome. Therefore, we should choose a safe, minimal dose that can achieve therapeutic goals in patients. In this study, we treated the PTM patient by multipoint subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone at a low dose and by topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment in order to compare the effects of the two therapies.

One and a half years ago, the patient had applied a halometasone ointment to treat the PTM in both his legs. The lesions improved within two weeks. However, it relapsed one week after discontinuing the halometasone. The skin of the lesions then thickened diffusely and gradually turned dark brown. After the application of multipoint subcutaneous injections of triamcinolone to the right lower extremity and the topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment for the left lower extremity, the thickness of the skin lesions diminished gradually. The changes in the thickness of the skin were similar between the two legs. In addition, the color of both lower extremities became lighter. Before treatment, the skin lesions were dark brown. During the course of treatment, the color gradually turned red and eventually yellow, similar to the normal color of the skin (Figure 6). The color of the right lower extremity with the intralesional glucocorticoid changed faster than that of the left lower extremity with halometasone ointment. After treatment, the side with the injections was preferred to peeling, and the new skin was not different from normal skin. The numbness in the patient’s legs and the acupuncture-like sensation improved during the course of treatment and completely remitted after the treatment. There were no obvious differences in the changes between the two legs except the color.

In terms of dose, we controlled the dose of the intralesional triamcinolone precisely and calculated the equivalent dose for the halometasone ointment. Therefore, we believe that the bilateral lower extremities received consistent doses of glucocorticoid. Judging from the current treatment results, it is not difficult to find that the effect of the intralesional glucocorticoid was equivalent to the application of glucocorticoid ointment. However, the use of intralesional corticoids has recently been demonstrated to have positive results with shorter treatment times[14]. This is different from our results and we speculate that intralesional glucocorticoids have a higher absorption rate and may enter the capillaries after the injection, which could lead to systemic reactions. Thus, the local injections of a glucocorticoid in the unilateral leg could have interfered with the other side. Therefore, randomized controlled trials are needed to evaluate the differences in the efficacy between intralesional glucocorticoids and glucocorticoid ointments for the treatment of PTM.

The change in thyroid function in this patient is interesting. Before PTM treatment, the TSH levels and FT3 levels were always abnormal. However, after PTM treatment, FT3 levels decreased gradually and were normal by the end of PTM treatment, although TSH was still at a low level with a slightly increasing trend. This may be explained by the following two possible causes. First, enough dosage of methimazole (30 mg daily) and regular administration may promote the improvement of thyroid function. Second, the immunosuppressive effects of glucocorticoids may inhibit TRAb and indirectly improve thyroid function. However, due to the limitation in the TRAb detection limit, we could not assess specific changes in TRAb titers; therefore, we could not confirm our speculation.

This article has the following limitations. First, due to the limitation in the detection limit of TRAb, we were unable to detect its precise change process. Second, a prolonged follow-up period is needed to evaluate the subsequent effects of PTM treatment. Third, this study was a self-controlled trial with a single individual. The bilateral treatment of both legs may have interfered with each other. Therefore, a large randomized controlled trial should be conducted to explore in detail the exact therapeutic effects of the two options for PTM treatment.

A 53-year-old man was diagnosed with hyperthyroidism. Swollen red areas with a diameter of about 5 cm and clear boundaries and a slightly tougher texture - but without itching - were found above both ankles.

It was clearly diagnosed as pretibial myxedema (PTM).

The patient underwent blood tests at our hospital, which indicated Graves’ disease (GD).

Imaging diagnosis

The patient underwent an imaging examination at our hospital, which indicated exophthalmos and hypertrophic osteoarthropathy.

The pathological examination confirmed the diagnosis of PTM.

Intradermal injections of triamcinolone acetonide was used for PTM of the right lower extremity. A halometasone ointment was used once a day for PTM of the left lower extremity.

The skin lesions treated using radiation therapy were reported in 2014. The lesions remitting 30 d after intralesional infiltration therapy was reported in 2015. One hundred and eleven cases of PTM treated by multipoint subcutaneous injections were reported in 2016. Sendhil Kumaran et al reported the treatment of 30 cases of PTM with a glucocorticoid in 2015.

Multipoint subcutaneous injections of a long-acting glucocorticoid and the topical application of a glucocorticoid ointment are both safe and effective, with the latter being a more convenient treatment for PTM in patients with GD.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: This report follows the guidelines of the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Demonacos C, Xavier-Elsas P S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Salvi M, De Chiara F, Gardini E, Minelli R, Bianconi L, Alinovi A, Ricci R, Neri F, Tosi C, Roti E. Echographic diagnosis of pretibial myxedema in patients with autoimmune thyroid disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 1994;131:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fatourechi V. Pretibial myxedema: pathophysiology and treatment options. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:295-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bartalena L, Fatourechi V. Extrathyroidal manifestations of Graves’ disease: a 2014 update. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014;37:691-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Anderson CK, Miller OF 3rd. Triad of exophthalmos, pretibial myxedema, and acropachy in a patient with Graves’ disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:970-972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Senel E, Güleç AT. Euthyroid pretibial myxedema and EMO syndrome. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2009;18:21-23. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Saito S, Sakurada T, Yamamoto M, Yamaguchi T, Yoshida K. Exophthalmus-myxoedema circumscriptum praetibiale-osteoarthropathia hypertrophicans (E.M.O.) syndrome in Graves’ disease: a review of eight cases reported in Japan. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1975;115:155-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bahn RS, Dutton CM, Heufelder AE, Sarkar G. A genomic point mutation in the extracellular domain of the thyrotropin receptor in patients with Graves’ ophthalmopathy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;78:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ramos LO, Mattos PC, Figueredo GL, Maia AA, Romero SA. Pre-tibial myxedema: treatment with intralesional corticosteroid. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:143-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lan C, Li C, Chen W, Mei X, Zhao J, Hu J. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intralesional Glucocorticoid for Treating Pretibial Myxedema. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:862-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lan C, Wang Y, Zeng X, Zhao J, Zou X. Morphological Diversity of Pretibial Myxedema and Its Mechanism of Evolving Process and Outcome: A Retrospective Study of 216 Cases. J Thyroid Res. 2016;2016:2652174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sendhil Kumaran M, Dutta P, Sakia U, Dogra S. Long-term follow-up and epidemiological trends in patients with pretibial myxedema: an 11-year study from a tertiary care center in northern India. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:e280-e286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Takasu N, Higa H, Kinjou Y. Treatment of pretibial myxedema (PTM) with topical steroid ointment application with sealing cover (steroid occlusive dressing technique: steroid ODT) in Graves’ patients. Intern Med. 2010;49:665-669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Schwartz KM, Fatourechi V, Ahmed DD, Pond GR. Dermopathy of Graves’ disease (pretibial myxedema): long-term outcome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:438-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Deng A, Song D. Multipoint subcutaneous injection of long-acting glucocorticid as a cure for pretibial myxedema. Thyroid. 2011;21:83-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vannucchi G, Campi I, Covelli D, Forzenigo L, Beck-Peccoz P, Salvi M. Treatment of pretibial myxedema with dexamethazone injected subcutaneously by mesotherapy needles. Thyroid. 2013;23:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ren Z, He M, Deng F, Chen Y, Chai L, Chen B, Deng W. Treatment of pretibial myxedema with intralesional immunomodulating therapy. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:1189-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim WB, Mistry N, Alavi A, Sibbald C, Sibbald RG. Pretibial Myxedema: Case Presentation and Review of Treatment Options. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2014;13:152-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |