Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.825

Peer-review started: August 5, 2018

First decision: August 31, 2018

Revised: September 21, 2018

Accepted: October 12, 2018

Article in press: October 11, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 114 Days and 1.6 Hours

The prevalence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is higher in southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan than in other areas in the world. Radiotherapy is an important part of treatment for NPC patients, especially those with stage III/IV disease. Subdural empyema is a rare but life-threatening complication in postradiotherapy NPC patients which should be paid more attention. Here, we present the case of a 64-year-old female postradiotherapy NPC patient with subdural empyema complicated with intracranial hemorrhage. She was treated by burr-hole surgery but unfortunately died because of recurrent intracranial hemorrhage. The mechanisms potentially underlying the formation of subdural empyema in postradiotherapy NPC patients and the surgical strategies that can be used in these patients are discussed in this report.

Core tip: This paper describes subdural empyema as a rare but life-threatening complication in postradiotherapy nasopharyngeal carcinoma. The opportunistic bacterial infection should be carefully considered in these immunosuppressive patients. A literature review was performed to discuss the potentially underlying mechanisms, imaging study, and comparison of two surgical strategies. It is noted that the prognosis appears to be more strongly related to the level of consciousness at the time of surgery.

- Citation: Chen JC, Tan DH, Xue ZB, Yang SY, Li Y, Lai RL. Subdural empyema complicated with intracranial hemorrhage in a postradiotherapy nasopharyngeal carcinoma patient: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 825-829

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/825.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.825

The prevalence of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) is higher in southern China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan than in other areas in the world[1]. Radiotherapy is an important part of treatment for NPC patients, especially those with stage III/IV disease. Here, we present the case of a 64-year-old female postradiotherapy NPC patient with subdural empyema complicated with spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage who was treated by burr-hole surgery. This case reveals that subdural empyema is a rare but life-threatening complication in postradiotherapy NPC patients which should be carefully considered. The mechanisms potentially underlying and surgical strategies for this condition are discussed in this report.

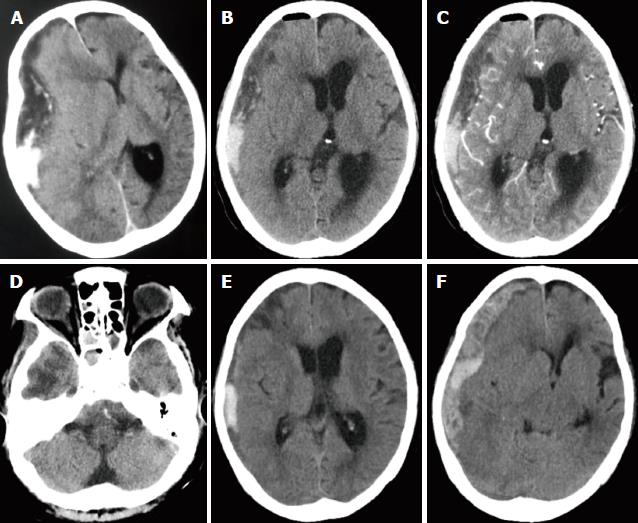

A 64-year-old woman was admitted after experiencing progressive headache, deteriorating consciousness, difficulty speaking, and weakness in left extremities for 2 d. Her past medical history was notable for T4N0M0 (Stage IVa) NPC and hypertension. She had received a long period of radiotherapy for cancer. There was no recent history of oral anticoagulants or head trauma. A neurologic examination revealed a comatose mental state with a Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score of 7 (E1M5V1). The right pupil was fixed and dilated and not reactive to light, whereas the left pupil was normal. Additional physical examination revealed fever (38.2 °C), left hemiparesis, and slight neck stiffness. Laboratory investigations showed leukocytosis (13.48 × 109/L) with neutrophilia (11.13 × 109/L). An elevated C-reactive protein level of 190 mg/L was also noted. A cranial CT was performed and showed a hypodense crescent-shaped accumulation of extra-axial fluid in addition to a local hyperdense lesion over the right hemisphere. There was a marked midline shift, and a tentorial herniation had formed (Figure 1A). We counseled her family and finally performed a burr-hole craniostomy with continuous closed system drainage under local anesthesia rather than a decompressive craniotomy due to her old age and poor health. A burr hole was made under CT guidance over the area of maximal lesion thickness. The dura and outer membrane were cross-incised, and we fixed an indwelling drainage catheter through the parietal burr hole under direct visualization. To our surprise, we found that the drainage of the lesion contained pus mixed with blood and was very viscous (Figure 2). An immediate postoperative cranial CT scan demonstrated that the subdural empyema had slightly decreased and that the middle structures of the brain had retracted (Figure 1B-D). In the following days, we empirically administered intravenous meropenem (0.5 g three times per day) and performed irrigation and drainage with 20 mL of saline containing gentamicin at a concentration of 0.32 mg/mL three times per day. On hospital day 4, the patient’s level of consciousness had slightly improved, and her GCS score was 10 (E4M5V1). A cranial CT scan revealed that the subdural empyema had significantly decreased and that a hematoma had formed (Figure 1E). While a culture of the operative empyema grew Corynebacterium corpse, the blood culture was negative. However, on day 5, the patient returned to a coma state (GCS3, E1V1M1). An urgent cranial CT scan showed that a new subdural hemorrhage had formed in the middle shift, and a tentorial herniation had reappeared (Figure 1F). Although emergency treatment was given, the patient died later that day.

Subdural empyema is usually regarded as a life-threatening emergency due to its association with a synergistic cascade of rapidly accumulating pus surrounding the brain, causing increased intracranial pressure and a mass effect, severe inflammatory edema, hydrocephalus, and infarction. These events can cause death; thus, an early and precise diagnosis and emergency treatment are critical[2].

Although extensive studies of central nervous system (CNS) infection have been performed in postradiotherapy NPC patients, subdural empyema is very rare, and only one case has been previously described in detail[3-5]. This previous study demonstrated that postradiotherapy NPC patients are prone to CNS infection for the following reasons. First, advanced NPC typically destroys the skull base and breaks down the CNS barrier[4]. It is important to note that temporal lobe necrosis (TLN), a late complication of radiotherapy in NPC patients, not only leads to various degrees of coagulative necrosis of the brain parenchyma which is associated with fibrinoid changes in blood vessels, but also disrupts the blood brain barrier, which can exacerbate CNS infection[6]. Finger-like hypodense regions indicate typical reactive white matter edema in the temporal lobe, which is a characteristic feature in the diagnosis of TLN[6,7] (Figure 1D). TLN is also likely to be a mechanism that drives recurrent intracranial hemorrhage, making its diagnosis and treatment a daunting challenge. Second, nasopharyngeal tumors often block the nasal airway and Eustachian tube, causing rhinosinusitis or otitis media, which can be exacerbated by radiation[4]. Finally, performing radiotherapy in NPC patients can cause myelosuppression and immunosuppression, thereby facilitating the rise of opportunistic infections[8]. In a case series of 699 patients, Nathoo et al[9] had described a bacteriological spectrum for cranial subdural empyema with Streptococcus species being the predominant causative organism followed by anaerobes and Staphylococcus aureus. These three types of bacteria are consistent with the most common causative agents found in sinusitis-associated subdural empyema patients[10]. By contrast, in our case, the pathogenic bacterium was confirmed as Corynebacterium corpse, which was not included in the common bacteriological spectrum. Corynebacterium species, which are commonly found in normal skin flora and are catalase-positive Gram-positive bacilli, are increasingly being recognized as causes of opportunistic disease in immunocompromised patients[11]. Our findings support the notion that subdural empyema in postradiotherapy NPC patients is caused by hematogenous seeding of opportunistic pathogenic bacteria rather than sinusitis.

A CT scan of the head is often the first means of identification in most emergency patients because of its more widespread availability and the need for a rapid diagnosis. However, it is worth noting that subdural empyema always mimics chronic or subacute subdural hematoma because they share comparable complaints and neurological symptoms and CT scan features, as observed in our case[3,12]. Subdural empyema commonly presents as the collection of hypodense crescent-shaped extra-axial fluid in a brain hemisphere, and it can cause a midline shift due to a mass effect. Enhancement of the adjacent cerebral cortex could be observed in many cases[13,14]. In addition to these findings, the sinuses might appear opacified, with air-fluid levels and bony erosion evident in some subdural empyema cases[15]. However, a CT scan might not show fluid collection when performed early in the evolution of the abscess, especially in abscesses in the infratentorial compartment[13,15]. Compared with a CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive and superior for diagnosing subdural empyema because it has better resolution, produces fewer artifacts, and can obtain multiplanar images[13,15,16]. Subdural empyema usually appears as hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images of subdual lesion[15]. Additionally, capsular enhancement is commonly noted after an intravenous gadolinium-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Gd-DPTA) injection[17]. Furthermore, compelling evidence indicates that diffusion-weighted images (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) on MRI play an essential role in distinguishing subdural empyema from reactive subdural effusion. Subdural empyemas have high signal intensity on DWI and low signal intensity on ADC maps, whereas subdural effusions have low signal intensity on DWIs[15,17].

There is a great deal of controversy regarding the surgical strategies that should be used to manage subdural empyema (i.e., craniotomy vs burr-hole surgery). A craniotomy is regarded as the best choice by some authors because it not only achieves decompression of the brain and returns cerebral blood flow but also allows the complete evacuation of purulent material, which is critical for a good prognosis[9,15,18]. Although craniotomy has many advantages, it might be rejected because of a patient’s old age or poor health or because of other risk factors associated with the use of general anesthesia. Burr-hole drainage has been recommended for acute-state patients with liquid and thin collection and can be accomplished using CT or MRI guidance[16]. A clinical study conducted by De Bonis et al[16] compared craniotomy and burr-hole surgery and demonstrated that the outcome and morbidity observed in subdural empyema survivors were not related to the surgical method used but rather to the patient’s level of consciousness at the time of surgery. However, reoperation is more frequent among patients who underwent burr-hole surgery[19], and this is an outcome that neurosurgeons are trying to improve. Eom and Kim[18] reported a case in which a favorable outcome was obtained using burr-hole surgery with continuous subdural irrigation and drainage of a subdural empyema.

Subdural empyema is a rare complication in postradiotherapy NPC patients which results from hematogenous seeding by opportunistic pathogenic bacteria rather than sinusitis. This life-threatening complication should be carefully considered and it should be noted that the prognosis of this condition appears to be more strongly related to a patient’s level of consciousness at the time of surgery than to the surgical method used to treat it.

A 64-year-old woman presented with a progressive headache, deteriorating consciousness, difficulty speaking, and weakness in the left extremities for 2 d.

Subdural empyema complicated with intracranial hemorrhage.

Chronic or subacute subdural hematoma.

While a culture of the operative empyema grew Corynebacterium, blood culture was negative.

A cranial CT showed a hypodense crescent-shaped accumulation of extra-axial fluid in addition to a local hyperdense lesion over the right hemisphere. There was a marked midline shift, and a tentorial herniation had formed.

A burr-hole craniostomy with continuous closed system drainage and use of antibiotics were administered to the patient.

A patient presenting with subdural empyema after completion of concurrent chemoradiotherapy for stage IVB nasopharyngeal carcinoma (NPC) has been reported in detail by Dr. Chan from Singapore National University Hospital in 2006.

Burr-hole craniotomy under CT or MRI guidance is an invasive surgical approach for chronic subdural hematoma or subdural empyema. Compared with craniotomy, burr-hole drainage can be performed under local anesthesia and is a less invasive surgical choice for patients with old age or poor health condition.

Subdural empyema is a rare but life-threatening complication in postradiotherapy NPC. It results from hematogenous seeding opportunistic pathogenic bacteria rather than sinusitis. Subdural empyema can mimic chronic or subacute subdural hematoma because of the similar clinical manifestations and imaging findings.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Coskun A, Noussios GI, Vaudo G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Wei WI, Sham JS. Nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Lancet. 2005;365:2041-2054. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 995] [Cited by in RCA: 1006] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Holland AA, Morriss M, Glasier PC, Stavinoha PL. Complicated subdural empyema in an adolescent. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2013;28:81-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chan DB, Ong CK, Soo RL. Subdural empyema post-chemoradiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:1089-1091. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Liang KL, Jiang RS, Lin JC, Chiu YJ, Shiao JY, Su MC, Hsin CH. Central nervous system infection in patients with postirradiated nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a case-controlled study. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fang PH, Lin WC, Tsai NW, Chang WN, Huang CR, Chang HW, Huang TL, Lin HC, Lin YJ, Cheng BC. Bacterial brain abscess in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma following radiotherapy: microbiology, clinical features and therapeutic outcomes. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen J, Dassarath M, Yin Z, Liu H, Yang K, Wu G. Radiation induced temporal lobe necrosis in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: a review of new avenues in its management. Radiat Oncol. 2011;6:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee AW, Ng SH, Ho JH, Tse VK, Poon YF, Tse CC, Au GK, O SK, Lau WH, Foo WW. Clinical diagnosis of late temporal lobe necrosis following radiation therapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Cancer. 1988;61:1535-1542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gaviani P, Silvani A, Lamperti E, Botturi A, Simonetti G, Milanesi I, Ferrari D, Salmaggi A. Infections in neuro-oncology. Neurol Sci. 2011;32 Suppl 2:S233-S236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Nathoo N, Nadvi SS, Gouws E, van Dellen JR. Craniotomy improves outcomes for cranial subdural empyemas: computed tomography-era experience with 699 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:872-877; discussion 877-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dill SR, Cobbs CG, McDonald CK. Subdural empyema: analysis of 32 cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:372-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bernard K. The genus corynebacterium and other medically relevant coryneform-like bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 2012;50:3152-3158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | de Beer MH, van Gils AP, Koppen H. Mimics of subacute subdural hematoma in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:634.e1-634.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bartt RE. Cranial epidural abscess and subdural empyema. Handb Clin Neurol. 2010;96:75-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zimmerman RD, Leeds NE, Danziger A. Subdural empyema: CT findings. Radiology. 1984;150:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Osborn MK, Steinberg JP. Subdural empyema and other suppurative complications of paranasal sinusitis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:62-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | De Bonis P, Anile C, Pompucci A, Labonia M, Lucantoni C, Mangiola A. Cranial and spinal subdural empyema. Br J Neurosurg. 2009;23:335-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wong AM, Zimmerman RA, Simon EM, Pollock AN, Bilaniuk LT. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging of subdural empyemas in children. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:1016-1021. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Eom KS, Kim TY. Continuous subdural irrigation and drainage for intracranial subdural empyema in a 92-year-old woman. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2011;54:87-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mat Nayan SA, Mohd Haspani MS, Abd Latiff AZ, Abdullah JM, Abdullah S. Two surgical methods used in 90 patients with intracranial subdural empyema. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16:1567-1571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |