Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.820

Peer-review started: July 30, 2018

First decision: September 13, 2018

Revised: October 17, 2018

Accepted: October 23, 2018

Article in press: October 22, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 125 Days and 3.7 Hours

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is a rare benign condition, which can mimic many other diseases because of their similarities in clinical, endoscopic and histological features. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/p) is a premalignant lesion in the colon and rectum. The misdiagnosis of SSA/p in SRUS patients has been noted, but the case of SRUS arising secondarily to SSA/p has been rarely reported. We herein report the case of a 59-year-old man who presented with an ulcerative nodular lesion in the rectum, accompanied by the symptoms of blood and mucus in the feces, diarrhea and constipation. Magnetic resonance imagining revealed thickening of the rectal mucosa-submucosa. Histologically, the lesion was characterized by the hyperplastic lamina propria and diffusely serrated crypts. Further immunohistochemical staining showed the loss of HES1 and MLH1 expression in the epithelial cells in the serrated area. The patient with SRUS had histological changes of SSA/p, suggesting a potential of tumor transformation in certain cases. SRUS uncommonly accompanied by serrated lesions should at least be considered by pathologists and clinicians.

Core tip: We report a 59-year-old man presenting with blood and mucus in the feces, diarrhea and constipation. A subsequent endoscopy of the rectum revealed a 5-cm ulcerative nodule in the anterior wall of the rectum, 5 cm from the anal verge. Abdominal magnetic resonance imagining revealed thickening of the mucosa-submucosa, raising suspicion of rectal carcinoma. The surgical resection of the rectum was performed. However, the final pathology suggested an unusual case of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome complicating sessile serrated adenoma/polyp.

- Citation: Sun H, Sheng WQ, Huang D. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome complicating sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 820-824

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/820.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.820

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is an uncommon benign disease, which is characterized by chronic defecation disorder. Along with the recognition of this disease, it has become clear that SRUS may not be solitary, ulcerative or indeed confined to the rectum[1]. SRUS can resemble other conditions in clinical presentation, endoscopic appearance and histopathologic feature[1-3]. Histologically, SRUS shows characteristic fibromuscular proliferation within the lamina propria accompanied by thickening of the muscularis mucosae. In some cases, there were focal serrated glands and dilated “diamond-shaped” crypts because of embedding artifact and architectural distortion[4,5]. These distorted crypts were the common reason for misinterpretation as sessile serrated adenoma/polyp (SSA/p)[6,7]. The majority of reports on the SRUS morphology have concentrated on its hyperplastic polyp (HP)-like architecture that is distinct from true serrated lesions[7,8], so that a diagnosis of SRUS often makes the pathologists believe that this lesion with serrated changes has no neoplastic potential. We herein report a case of SRUS complicating SSA/p, highlighting the need for careful histological assessment of serrated lesions in the polypoid mucosal prolapse with serrated architecture.

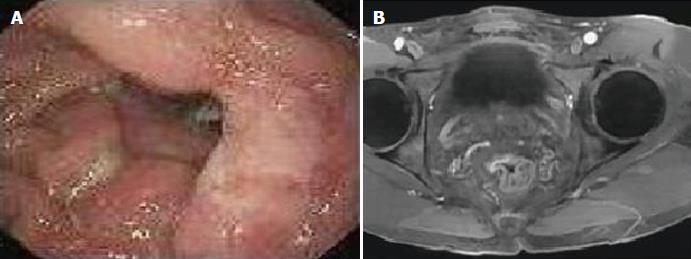

A 59-year-old man visited a local hospital with a 3-year history of occult blood and mucus in the feces, and with a long history of intermittent episodes of diarrhea and constipation. The patient had no history of steroid use, chronic liver disease, viral hepatitis, autoimmune diseases, or neoplasm. Physical examination was unremarkable except for a lump palpable on the anterior wall of the rectum 5 cm from the anal verge. Occult blood was detected in his feces. Other laboratory studies were normal, and carcinoembryonic antigen was not elevated. A subsequent endoscopy of the rectum revealed a 5-cm ulcerative nodule in the anterior wall of the rectum, 5 cm from the anal verge (Figure 1A). Initial endoscopic biopsy was performed in the local clinic and histopathologic finding was a rectal adenoma with low-grade dysplasia. After three months, a repeated colorectal endoscopy showed an ulcerative rectal mucosa and granulation tissue with no evidence of malignancy. However, the findings of abdominal magnetic resonance imagining (MRI) revealed thickening of the mucosa-submucosa, raising suspicion of rectal carcinoma (Figure 1B). In addition, clinical symptoms persisted despite medical treatment. Therefore, surgical resection of the rectum was performed. The final pathology report was no malignancy. Thus, the patient was referred to our hospital for the pathology consultation.

Grossly, a well-demarcated, superficial ulcer with polypoid mucosa involved almost the entire circumference of the rectum 5 cm from the anal dentate line. The ulcerative nodular lesion measured 5 cm × 4 cm in length and width (described in the pathological report at the local clinic).

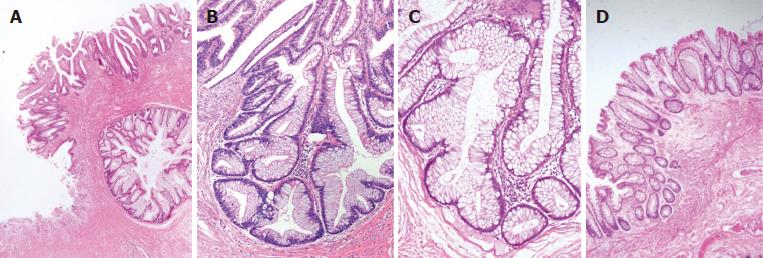

Histological examination revealed fibromuscular obliteration in the lamina propria combined with a superficial ulcer, which is surrounded by a large amount of serrated crypts (Figure 2A). These irregular glands showed a saw-toothed pattern or a diamond-shaped architecture involving the base of crypts (Figure 2B). The epithelial cells lined in the crypts were characterized by mucin hypersecretion and slight nuclear stratification (Figure 2C), which is consistent with the pathological characteristics of SSA/p. Around the SSA/p area, micro-vesicular hyperplastic polyps (MVHPs) were found, showing the earliest lesions of serrated dysplasia (Figure 2D).

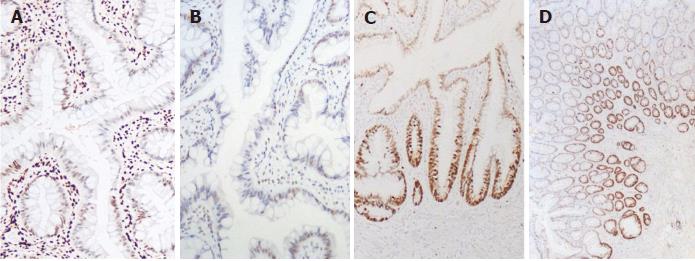

Immunostaining for HES1 showed loss of expression in the serrated glands, while nuclear staining was observed in the normal adjacent epithelium and interstitial inflammatory cells (Figure 3A). Similarly, there was superficial loss of MLH1 expression in the crypts with serrated architectures (Figure 3B). However, proteins encoded by other mismatch repair genes, such as MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2, were nuclear positive in all cells. The staining for β-catenin was diffusely positive along the cell membranes, and P53 showed focal nuclear positivity. Ki-67 staining increased in the crypts of SSA/p (Figure 3C), compared with the basal staining in glands of MVHPs (Figure 3D).

SRUS is a poorly understood syndrome that was originally described in 1829 since Cruveihier reported four cases of unusual rectal ulcers[9]. The term “SRUS” was widely accepted after the initial use by Madigon and Morson[10] in the late 1960s. This syndrome usually manifests as rectal bleeding, prolonged excessive straining, copious mucus passing and abdominal pain[11]. Ulcers and polyps have been the common endoscopic findings in 90% of patients[12,13]. However, some of the clinical and endoscopic presentations in SRUS patients can be completely nonspecific, and up to 26% of patients may be asymptomatic[1,14]. Hence, it is difficult to distinguish SRUS from malignancy or other diseases based on symptoms, endoscopic features or image findings[15]. Misdiagnosis of SRUS as malignancy can lead to unnecessary surgery. Herein, we present a 59-year-old man originally suspected of having rectal malignancy. An abdominoperineal resection of the rectum was performed and the final diagnosis was SRUS with SSA/p. Endoscopic examination in our case suggested a malignancy. However, MRI images showed that the lesion was not a mass but thickening of the mucosa-submucosa. This is a key point of differentiation between SRUS and cancer in imaging techniques. At present, conservative measures (diet and bulking agents) and biofeedback therapy are the first choice in SRUS treatment. Surgery usually acts as the final opinion for patients who have repeated relapse[16].

SRUS accompanied by SSA/p is extremely rare, and an accurate differential diagnosis is difficult to achieve. In our case, the histopathologic alterations of SRUS are characteristic and include the hyperplasia of the smooth muscle and thicken of the muscularis mucosae. Moreover, colonic crypts around the ulcer were no longer rounded but have diffusely serrated changes. These hypermucinous glands showed crypt dilatation and crypt flattening at the base. Surrounded by typical HPs, these serrated changes are reminiscent of a diagnosis of SSA/p. The differential diagnosis included inflammatory cloacogenic polyp with SRU, which was an inflammatory polyp of the anorectal transition zone[17]. Since previous studies have reported that the distortion and entrapment of the crypts were the common reasons for misinterpretation of SSA/p[5,8], the tumor location, diffuse HPs around the serrated changes and the striking features of SSA/p confirmed the final diagnosis of SRUS coexisting with SSA/p in our case.

Previous research illustrated that loss of HES1 expression could distinguish SSA/p from regenerative epithelia or HPs[18]. Interestingly, we found that HES1 expression was absent in the serrated glands. As the downstream target of the Notch signaling pathway, HES1 might be involved in the regulation of molecular activation and tumorigenesis in SRUS with SSA/p. Besides, some investigators showed that MLH1 deficiency was associated with the progression of sessile serrated lesions[19]. Moreover, a previous study has reported that some cases of SRUS with HP-like architectures presented focal loss of MLH1 expression, suggesting a potential of preneoplastic change in some SRUS cases[8]. Similar results were obtained in our case, which showed that the serrated crypts were negative for MLH1 staining while proteins encoded by other mismatch repair genes were normally expressed. Likewise, it has been discovered that the proliferation marker Ki67 is of value in assessing SSA/p. The Ki-67 proliferative zone tended to be distributed diffusely in the base of the SSA/p crypts, but partially in the epithelium of the normal or HP glands[20]. For our case, the basal cells within serrated crypts demonstrated diffuse staining for Ki-67, which is consistent with the features of SSA/p.

Little is known regarding the biologic characteristics and natural history of serrated lesions in SRUS. It is generally accepted that inappropriate and paradoxical contraction of the pelvic floor, which causes straining at defecation and prolapse of the rectal mucosa, further results in ulceration and polyps in SRUS patients[21-23]. Repeated trauma and repair are commonly observed in SRUS, which may be the reason of neoplastic transformation. Further studies are needed to clarify the pathogenic relationship between SRUS and tumors. Our case presented the loss of HES1 and MLH1 expression in serrated crypts, suggesting that HES1 and MLH1 may act as molecular triggers in the formation of serrated neoplasia in SRUS.

In summary, we have described an unusual case of SRUS complicating SSA/p. Loss of HES1 and MLH1 expression occurs in the serrated crypts, suggesting that alterations in molecular pathways may promote SSA/p progression in certain cases of SRUS. Pathologists and clinicians should be aware of the potential for serrated lesions to develop in SRUS.

Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome (SRUS) is an uncommon benign disease. It has been reported previously, but the case of SURS arising secondarily to sessile serrated adenomas/polyp (SSA/p) has been rarely reported.

Rectal ulcer.

Rectal cancer.

Blood and mucus were detected in the feces.

Thickening of the rectal mucosa-submucosa.

SRUS with SSA/P.

Mainly medical therapy, and if not relieved, surgical management is indicated.

A review of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome has been reported by Ala I Sharara in the Journal of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy.

SRUS: Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome; SSA/p: Sessile serrated adenomas/polyp.

This case will contribute to improvements in our understanding of SRUS with SSA/P. This case may also serve as a reminder to gastroenterologists, surgeons and pathologists who may encounter SRUS cases in their clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Dogan UB, Lee CL, Osawa S S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Abid S, Khawaja A, Bhimani SA, Ahmad Z, Hamid S, Jafri W. The clinical, endoscopic and histological spectrum of the solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: a single-center experience of 116 cases. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Levine DS, Surawicz CM, Ajer TN, Dean PJ, Rubin CE. Diffuse excess mucosal collagen in rectal biopsies facilitates differential diagnosis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome from other inflammatory bowel diseases. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:1345-1352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tsuchida K, Okayama N, Miyata M, Joh T, Yokoyama Y, Itoh M, Kobayashi K, Nakamura T. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome accompanied by submucosal invasive carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2235-2238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chetty R, Bhathal PS, Slavin JL. Prolapse-induced inflammatory polyps of the colorectum and anal transitional zone. Histopathology. 1993;23:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Huang CC, Frankel WL, Doukides T, Zhou XP, Zhao W, Yearsley MM. Prolapse-related changes are a confounding factor in misdiagnosis of sessile serrated adenomas in the rectum. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singh B, Mortensen NJ, Warren BF. Histopathological mimicry in mucosal prolapse. Histopathology. 2007;50:97-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brosens LA, Montgomery EA, Bhagavan BS, Offerhaus GJ, Giardiello FM. Mucosal prolapse syndrome presenting as rectal polyposis. J Clin Pathol. 2009;62:1034-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ball CG, Dupre MP, Falck V, Hui S, Kirkpatrick AW, Gao ZH. Sessile serrated polyp mimicry in patients with solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: is there evidence of preneoplastic change? Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2005;129:1037-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cruveilhier J. Ulcere chronique du rectum. Anatomie pathologique du corps humain. Paris: JB Bailliere. 1829;. |

| 10. | Madigan MR, Morson BC. Solitary ulcer of the rectum. Gut. 1969;10:871-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Geramizadeh B, Baghernezhad M, Afshar AJ. Solitary Rectal Ulcer: A literature review. Ann Colorectal Res. 2015;3:33500. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Van Outryve MJ, Pelckmans PA, Fierens H, Van Maercke YM. Transrectal ultrasound study of the pathogenesis of solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Gut. 1993;34:1422-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Li SC, Hamilton SR. Malignant tumors in the rectum simulating solitary rectal ulcer syndrome in endoscopic biopsy specimens. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:106-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Church JM, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Milsom JW. Clinical conundrum of solitary rectal ulcer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35:227-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tjandra JJ, Fazio VW, Petras RE, Lavery IC, Oakley JR, Milsom JW, Church JM. Clinical and pathologic factors associated with delayed diagnosis in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:146-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhu QC, Shen RR, Qin HL, Wang Y. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment strategies. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:738-744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 17. | Saul SH. Inflammatory cloacogenic polyp: relationship to solitary rectal ulcer syndrome/mucosal prolapse and other bowel disorders. Hum Pathol. 1987;18:1120-1125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cui M, Awadallah A, Liu W, Zhou L, Xin W. Loss of Hes1 Differentiates Sessile Serrated Adenoma/Polyp From Hyperplastic Polyp. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee EJ, Chun SM, Kim MJ, Jang SJ, Kim do S, Lee DH, Youk EG. Reappraisal of hMLH1 promoter methylation and protein expression status in the serrated neoplasia pathway. Histopathology. 2016;69:198-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fujimori Y, Fujimori T, Imura J, Sugai T, Yao T, Wada R, Ajioka Y, Ohkura Y. An assessment of the diagnostic criteria for sessile serrated adenoma/polyps: SSA/Ps using image processing software analysis for Ki67 immunohistochemistry. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Morio O, Meurette G, Desfourneaux V, D’Halluin PN, Bretagne JF, Siproudhis L. Anorectal physiology in solitary ulcer syndrome: a case-matched series. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1917-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kang YS, Kamm MA, Engel AF, Talbot IC. Pathology of the rectal wall in solitary rectal ulcer syndrome and complete rectal prolapse. Gut. 1996;38:587-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Vaizey CJ, van den Bogaerde JB, Emmanuel AV, Talbot IC, Nicholls RJ, Kamm MA. Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1617-1623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |