Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.811

Peer-review started: August 23, 2018

First decision: October 4, 2018

Revised: October 16, 2018

Accepted: October 23, 2018

Article in press: October 22, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 95 Days and 22.4 Hours

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) is a rare tumour that often occurs in soft tissues of the female genital tract. Eight cases of AAM are reported in this article, and the clinical features and ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) results of the eight cases are reviewed and summarized. The main complaints of all the patients were palpable and painless masses in the vulva or scrotum. The lesions were mainly located in the vulva, pelvis, and perineal region, with a large scope of involvement. The sonographic features of AAM were characteristic. On sonography, all of the masses were of irregular shape and showed hypoechogenicity, with a heterogeneous inner echotexture. Intratumoural and peritumoural blood flows were detected by colour Doppler imaging. On real-time ultrasonic imaging, prominent deformation of the lesions was observed by compressing the masses with the probe. Some special imaging features were also revealed, including a laminated or swirled appearance of inner echogenicity, and a finger-like or tongue-like growth pattern. On MRI imaging, the lesions showed intermediate-intensity signals and intermediate to high-intensity signals on TI-weighted and T2-weighted sequences. A rapid and uneven enhancement pattern was demonstrated. After the comparison of sonographic features with MRI and pathological findings, we found the relevance of the ultrasonographic characteristics with MRI and histological features of AAM. Ultrasound can be a valuable imaging method for the preoperative diagnosis, evaluation of scope, and follow-up of AAM.

Core tip: Eight cases of aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) were collected in this manuscript. The lesions of AAM appear as irregular hypoechoic masses with internal echogenicity and well-defined borders on ultrasonic imaging. Some special imaging features of AAM, such as laminated or swirled sign and finger-like growth pattern, can also be seen on ultrasound examination. The abundant intratumoral blood flows on colour Doppler ultrasound is a distinctive feature of AAM, which can be a crucial clue for the diagnosis. These ultrasonic features of AAM correlate with the findings of magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Ultrasound can be utilized in the preoperative diagnosis and follow-up of AAM.

- Citation: Zhao CY, Su N, Jiang YX, Yang M. Application of ultrasound in aggressive angiomyxoma: Eight case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 811-819

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/811.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.811

Aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM), a rare neoplastic disease, was first reported by Steeper et al[1] in 1983. AAM usually occurs in females aged 15-60 years, and affects the female genital tract and pelvic soft tissues[2]. Cases of AAM located in the male spermatic cord and scrotum have also been reported[3]. Patients often visit hospital because of a palpable mass in the vulva or incidental imaging findings without other discomforts. Imaging options for AAM include ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and some typical imaging features of AAM can be observed with different modalities[4,5]. Surgery is the main method for the treatment of AAM. AAM is a benign disease originating from mesenchymal tissues, with a tendency for local aggression. Therefore, a complete surgical resection of the lesion of AAM is required. The recurrence rate after surgical excision of AAM is high, and regular follow-ups through imaging methods are essential[6]. In this article, eight cases of AAM are reported. These patients were referred to Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) from 2002 to 2016, underwent surgery in the Department of Gynecology and the Department of Urological Surgery. We review the clinical features and ultrasound and MRI results of the eight cases, and summarize the ultrasonographic characteristics of AAM. The value of ultrasound in the diagnosis of AAM is discussed based on the comparison of sonographic features with MRI and pathological findings.

A 40-year-old woman was referred to PUMCH with a complaint of discomfort and swelling of the left buttock for 4 years, and a palpable mass in the left vulva for 1 year. Clinical examination found a massive lesion ranging from the deep pelvis to the left vulva. An irregular hypoechoic mass with well-defined margins was visualized by US. The mass was located on the left side of the perineum and extended anteriorly to the anus. The internal echogenicity was demonstrated as heterogeneous. On colour Doppler ultrasound, a blood pattern of abundant internal and external vessels was visualized. The patient received surgery for a complete removal of the lesion, which was found to be very large and extend to the left inguinal region. The lesion was finally diagnosed as an AAM mass by postoperative pathology and immunohistochemical examination.

A 38-year-old woman was referred with a 6-year history of a gradually increasing mass on the vulva. She had undergone surgery for a vulvar mass resection 8 years previously, and the mass was identified as an AAM after pathological examination. A huge vulvar mass extending to the vagina and cervix was detected by clinical examination. US revealed a hypoechoic lesion with distinct borders, ranging from the right side of the vulva to posterior to the uterus. The size was 7.2 cm × 5.6 cm × 14.6 cm, and internal blood vessels were demonstrated on colour Doppler ultrasound. During surgery, a large mass with a diameter of 14 cm was identified and removed from the soft tissues, and was verified as an AAM by postoperative pathology.

A 40-year-old woman complained of an egg-like mass on the left labia majora, which had obvious enlargement since it was found 2 years ago. Clinical examination found a vulvar lesion extending to the pelvis. On US, an irregular lesion anterior to the bladder, which extended to the left perineum and was approximately 17.1 cm × 10.6 cm × 8.9 cm in size, was identified. The internal texture was heterogenous, and the swirl sign was observed. Rich blood vessels were also detected. The mass presented with iso-intensity on T1 sequence and iso-hyper intensity on T2 sequence. Heterogeneous enhancement of the T1 sequence was seen after injection of a contrast agent. A complete resection of the mass was implemented successfully. During the following microscopic examination, spindle-like cells with abnormal nuclear atypia and mitoses were found in the myxoid background. The mass was finally diagnosed as an AAM after immunohistochemical examination.

A 35-year-old woman presented with a 10-year history of swelling of the left labia majora without any discomfort. The patient was referred to a local hospital one year ago, where a massive tumor was found by ultrasound. Clinical examination showed a soft vulvar neoplasm extending to the vagina. The US examination in our hospital demonstrated a hypoechoic mass on the left side of the uterus, measuring 16.2 cm × 6.9 cm × 7.4 cm and ending at the proximal left humerus. Internal and external blood vessels were clearly seen on colour Doppler ultrasound. MRI showed a mass with iso-intensity on T1 sequence, iso-hyper intensity on T2 sequence, and heterogeneous enhancement after injection of a contrast agent. The mass was diagnosed as an AAM by histological examination after biopsy. The patient underwent a regular gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-α) treatment, and received surgery after shrinking of the mass. The diagnosis of AAM was confirmed by postoperative pathology.

A 64-year-old man was referred with a complaint of a gradual enlargement and swelling of the right scrotum for 7 mo. A large and painless tumor in the right scrotum was verified by clinical examination. A well-defined, hypoechoic, and heterogeneous mass from the top of the scrotum to the right spermatoid cord was visualized by US, with a length of approximately 10 cm. On MRI, the mass showed hyper-intensity on T1 sequence, iso-hyper intensity on T2 sequence, and heterogeneous enhancement with multiple irregular enhancement areas. Surgical treatment was recommended for the patient, and the mass was identified as an AAM by histological and immunohistochemical examinations.

A 38-year-old woman complained of a recurrent mass of on the left vulva after resection of a left vulvar AAM 3 years ago. She planned to receive a surgery for further identification of the new mass. Clinical examination found a soft mass from the deep pelvis to the left vulva. A well-defined hypoechoic mass from the posterior wall of the vagina was observed by US examination. Uneven internal echotexture and rich blood signals were evident on US. MRI showed a mass with iso-intensity on T1 sequence and iso-hyper intensity on T2 sequence. The mass was diagnosed as a recurrent AAM tumour.

A 45-year-old woman presented with a pelvic mass of 8 cm found by US on a regular scan, without any complaint. Clinical examination found a large and irregular tumor posterior to the uterus. US in our hospital revealed a 12.3 cm × 8.8 cm × 6.3 cm hypoechoic mass in the Douglas pouch, with a relatively distinct boundary with the rectum and uterus, extending to the left vulva. Hyperechoic bands were observed inside the mass, and blood signals could also be detected. The mass was completely resected and diagnosed as an AAM lesion by pathology.

A 34-year-old woman presented with a palpable mass in the left vulva without any discomfort. Clinical examination found a soft mass that extended from the left vulva to the pelvis. US showed an 11 cm-long hypoechoic mass with heterogenous internal echotexture and abundant blood signals in the left posterior region of the uterus. During surgery, a grey soft mass with a length of 10 cm was seen, extending to the left back pelvis. The lesion was completely removed for histological examination, and was then identified as an AAM.

Clinical information for the eight AAM cases is listed in Table 1. The study included 7 females and 1 male, aged from 35 to 64 (median 39) years. Three cases were recurrent AAM, and the patients were hospitalized for a second surgery. All of the patients were examined by ultrasound, and four of eight patients had an MRI examination before surgery. The main complaints of all the patients were palpable and painless masses in the vulva or scrotum. Other symptoms, such as abdominal discomfort and dysmenorrhea, were also mentioned.

| Case No. | Gender | Age | Newly diagnosed/recurrent | Location | Maximal diameter (cm) |

| 1 | F | 40 | Newly diagnosed | Left side of the perineum - anterior to the anus | 21 |

| 2 | F | 38 | Newly diagnosed | Right side of the vulva - posterior to the uterus | 16 |

| 3 | F | 40 | Recurrent | Left to the perineum - anterior to the bladder | 17 |

| 4 | F | 35 | Recurrent | Proximal end of the left humerus - left side of the uterus | 18 |

| 5 | M | 64 | Newly diagnosed | Right spermatic cord - the top of the scrotum | 10 |

| 6 | F | 38 | Recurrent | Posterior wall of the vagina | 7 |

| 7 | F | 45 | Newly diagnosed | Posterior to the uterus | 12 |

| 8 | F | 34 | Newly diagnosed | Left posterior to the uterus | 11 |

According to the overall evaluation of the surgical specimens, the lesions of female patients were mainly located in the vulva, pelvis, and perineal region with a large scope of involvement. In the male patient, the mass was located in the spermatic cord and scrotum. The maximal diameters of the lesions ranged from 7 to 21 cm.

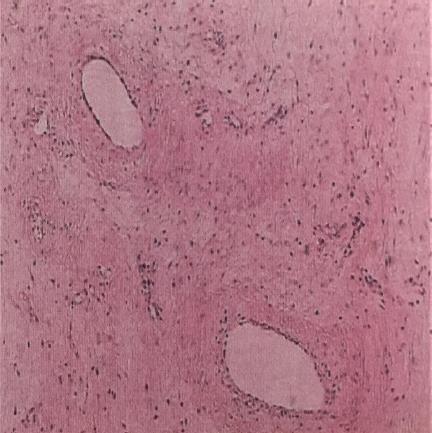

The diagnosis of AAM was affirmed on the basis of the pathologic features of the surgical specimens. Scattered spindle-formed cells were found in the myxoid and collagen background. These cells were characterized by abnormal nuclear atypia and mitoses. A variety of internal vessels were also seen in the samples after haematoxylin-eosin staining. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed positive staining for CD34, smooth muscle actin, desmin, estrogen receptors (ER), and progesterone receptors (PR) in these samples, which also supported the diagnosis of AAM (Figure 1).

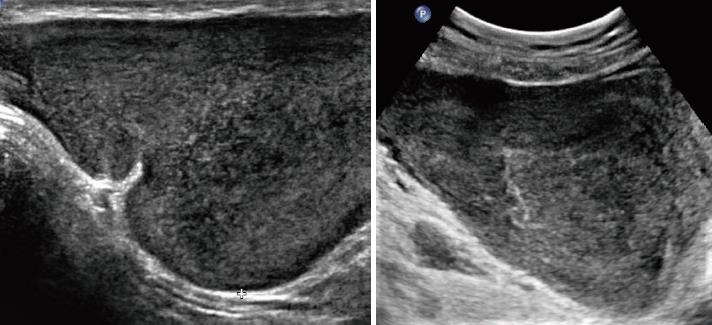

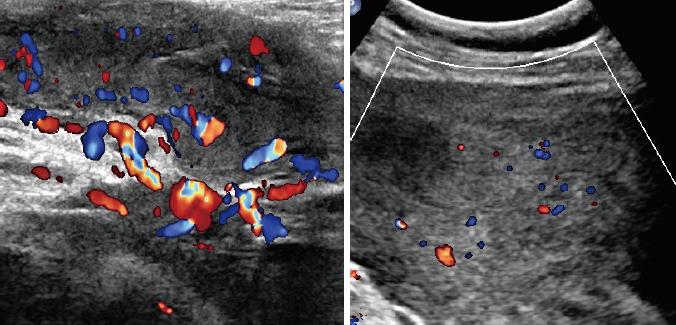

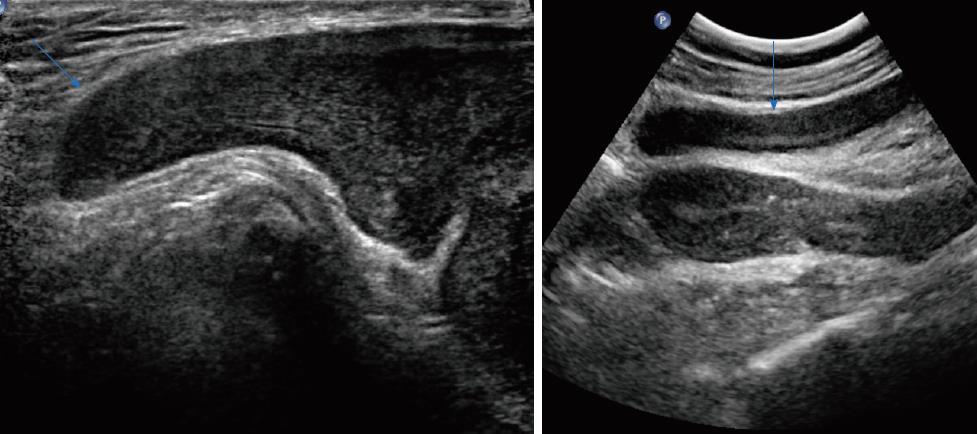

Table 2 shows the sonographic features of the lesions. All of the masses were of irregular shape. Seven (87.5%) of the masses had relatively smooth well-defined margins with surrounding tissues, and a hyperechoic rim could be seen at the border of the lesion. Only one lesion from a female patient was poorly defined. All of the eight cases appeared as a hypoechoic mass with heterogeneous inner echogenicity (Figure 2). Intratumoural and peritumoural blood flows were detected in all of the eight cases by colour Doppler ultrasound (Figure 3). On real-time ultrasonic imaging, prominent deformation of the lesions could be observed after putting pressure on the lesions, indicating the soft texture of AAMs.

| Case No. | Overall appearance | Shape | Margin | Internal echogenicity | Blood flow in CDFI |

| 1 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 2 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 3 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 4 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Poorly-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 5 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 6 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 7 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

| 8 | Hypoechoic lesion | Irregular | Well-defined | Heterogeneous, isoechoic internal components | Positive |

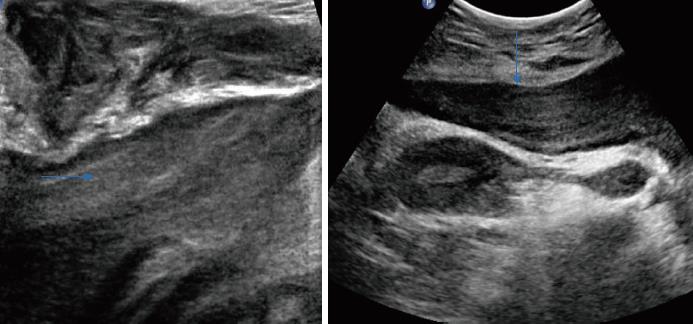

Apart from the imaging results mentioned above, some special sonographic features were detected by the radiologists. The inner isoechoic to hyperechoic bands possessed a laminated or swirled appearance, stretching the lesions (Figure 4). On the edge of the lesions, a finger-like or tongue-like growth pattern was observed, as the tumors tended to infiltrate into the gaps of surrounding soft tissues (Figure 5). Small anechoic areas in the lesions were also be mentioned by two of the reports, indicating the internal cystic degeneration.

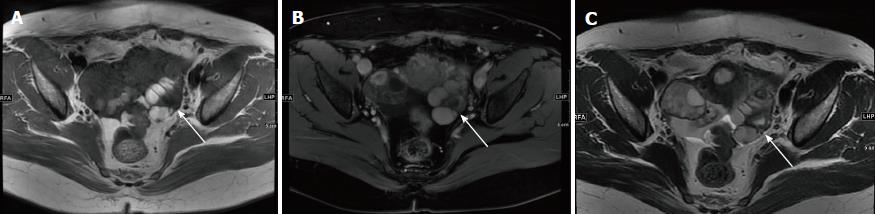

MRI results showed that the lesions possessed intermediate signal intensity and intermediate to high signal intensity on T1-weighted and T2-weighted sequences (Figure 6). Inhomogeneous MR signal intensity was demonstrated in these cases. The swirl sign was visualized on T2WI as swirled areas of low signal in a high-signal background. For the patients who had contrast-enhanced MRI examination, a rapid and heterogeneous enhancement pattern was observed (Table 3).

| Case No. | TI-weighted | T2-weighted | Contrast-enhanced pattern |

| 2 | Isointensity | Iso-hyperintensity, heterogeneous | Heterogeneous enhancement |

| 3 | Isointensity | Iso-hyperintensity, heterogeneous | * |

| 4 | Hyperintensity | Iso-hyperintensity, heterogeneous | Heterogeneous enhancement with multiple irregular enhancement areas |

| 5 | Isointensity | Iso-hyperintensity, heterogeneous | Heterogeneous enhancement |

AAM is a kind of benign neoplastic disease that originates from mesenchymal tissues, with extensive local invasiveness and a high recurrence rate[6]. The disease presents predominantly in females in the reproductive age[7]. Most cases were reported to appear in the pelvic and perineal regions of females[4,8,9]. There were also cases occurring in the scrotum, spermatic cord, and pelvic organs of males, mainly elderly ones[10,11]. In this article, we also report a man in his 60s with AAM in the scrotum. Cases of children diagnosed with AAM have also been reported[3]. The lesions of AAMs could also occur in rare regions, including the head and neck[12,13].

Apart from gradually enlarging masses in some patients, most patients with AAM declare no evident symptoms, and some may also complain of abdominal distention, perineovulvar swelling, or urinary irritation[14]. Imaging plays an essential part in the preoperative diagnosis and management of AAMs, including US, CT, and MRI[15]. The role of the imaging modalities would be discussed in this article. The final diagnosis of AAM depends on the postoperative pathology. The surgical specimen of AAM presents as a large, gray mass with gelatinous appearance and marked vascularization. Under a microscope, the lesions were found to be constituted by spindle cells scattered in a myxoid and collagen background with abundant vessels. The positive immunohistochemistry results of vimentin, desmin, SMA, CD34, ER, and PR are suggestive of the diagnosis of AAM[16-18].

Due to its aggressiveness, radical surgery is recommended for AAM, and complete excision is crucial[14,19]. GnRH-α can also be applied as an assistant drug therapy[20,21]. The postoperative recurrence rate of AAM has been estimated to be around 40%[1,22,23]. Remote metastasis of AAM was also reported[24]. As a consequence, regular follow-ups should be performed on all patients because of the high recurrence rate[14].

Ultrasound, CT, and MRI are the common imaging diagnostic methods for AAM, and MRI is the most widely used technique to identify the characteristic manifestations of AAM, including low or intermediate signal intensity on T1-weighted images and a high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, as well as the swirled configuration, which is described as swirling and laminated low-signal bands in a high-intensity background of water[25-27]. The behavior of AAM on the dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) sequence can also be distinguished. A layered or swirled enhancement pattern of AAM on DCE sequence was presented by several studies[5,28]. It was also reported that AAMs demonstrated high signal intensity on diffusion-weighted imaging with high mean values in the apparent diffusion coefficient maps[5,15,29].

Ultrasound is the first choice for screening pelvic lesions before performing further imaging techniques. Based on the ultrasound results of the eight cases, characteristics of AAMs on ultrasound imaging were determined. AAM lesions were irregular and hypoechoic masses with a large scope of involvement and relatively well-defined margins. The lesions had intermediate to high echogenicity with a layered or swirled arrangement. Finger-like or tongue-like growth patterns were visible in some cases, as a result of infiltrative growth into the gaps of surrounding soft tissues. Prominent deformity of the lesions was shown on real-time ultrasonic imaging after the masses were compressed by probes, which verified the soft texture of AAMs. Moreover, abundant blood flow was detected inside and around the masses on colour Doppler ultrasound.

The ultrasonic features of AAMs observed in our study corresponded well with the recent literature. An AAM case report in 2012 described the lesion as a large hypoechoic to isoechoic mass on transvaginal ultrasound examination, with internal septa of high echogenicity, and rich blood signals scattering throughout the tumor on colour Doppler sonography[30]. Another case in 2013 also presented as a hypoechoic and heterogeneous mass with well-defined margins, abundant internal vascularity, and peripheral blood vessels[31]. The swirled sign observed on both ultrasound and MRI has also been mentioned by a recent study[26]. While in the case reports in 1990s and early 2000s, AAMs were described as hypoechoic or cystic masses without additional imaging information, which may be due to the limited resolution of ultrasound modalities in earlier years[32,33].

Comparing the findings of ultrasound, MRI, and pathologic examinations of AAMs in this study, a consensus on imaging and histologic features can be reached. The overall hypoechoic patterns were due to the myxoid background and sparse tumor cells. The fibrovascular stroma presented as isoechoic to hyperechoic components or septa with swirled or laminated appearance on US because of the woven fibers stretching in the myxoid background. The finger-like growth pattern on the ultrasonic imaging indicated aggressive growth into surrounding tissues. Internal cystic degeneration could be seen as round anechoic areas. The soft texture of the lesions was delineated as deformity on real-time ultrasound after probe compression, due to the high water-content of AAMs. The affluent blood flow patterns shown on colour Doppler ultrasound illustrated the masses’ collateral vessels.

AAMs can be easily confused with other common asymptomatic masses in the perineal and pelvic regions, including vulvar abscess, Bartholin’s duct cyst, Gartner’s duct cyst, vaginal prolapse, levator hernia[34], and other types of rare soft tissue masses in the female genital tract, such as angiomyofibroblastoma (AMFB), myxoma, myxoid sarcoma, infiltrating angiolipoma, and myxoid liposarcoma[35]. To some extent, ultrasound can be helpful in differentiating AAM from other soft tissue tumours. Ota et al[30] also suggested that performing preoperative ultrasound can be helpful in excluding some other possible types of perineal masses.

For instance, Batholin’s gland cyst appears as a pure or complex cyst with isoechoic contents on US. In addition, no blood flow within the mass can be visualized on colour Doppler ultrasound, which is a major evidence for differentiation. Another rare mesenchymal tumor, AMFB, is difficult to be differentiated from AAM, of which the clinical and pathological characteristics overlapped with AAM. The prognosis of AMFB is better than that of AAM, with a lower recurrence rate. Therefore, it is important to clearly identify the pathological type to specify next medical plans[36]. One differential point of clinical features is that AMFB usually has smaller volume of less than 5 cm. Moreover, AMFB tends to be less invasive than AAM. Sonographically, AFMB can be a relatively homogeneous isoechoic mass, or generally an echogenic lesion with multiple hypoechoic areas. The margins of AMFB in sonography were reported to be well-defined, while AAM has rather infiltrative signs. And blood flows within the mass can also be detected by colour Doppler ultrasound[37]. Apart from postoperative histology, contrast-enhanced MRI can be helpful in differential diagnosis, when homogeneous enhancement is visualized rather than the swirled sign[38]. Other rare soft tumors, such as infiltrating angiolipoma and myxoid liposarcoma, may be delineated as a hyperechoic mass on ultrasound imaging due to the fat contents, which can differ from AAM. Superficial angiomyxoma is usually a subcutaneous multinodular mass, with small-sized, thin-walled blood vessels that lack the hypertrophic vessels and infiltrative nature of AAM[35].

To achieve complete surgical excision and minimal invasiveness, it is essential to apply an imaging method to evaluate tumor range before operation. A combination of transabdominal, transperineal, and transvaginal US scans may be helpful for proper assessment of the involved scope, and a previous case report also made the same assessment[19]. Long-term and regular follow-up plays a crucial role in promoting the patients’ prognosis. Ultrasound can also be applied for follow-up of patients after surgery and pharmacological treatment, because of its cost-effectiveness and convenience.

Based on the results of eight cases of AAMs, the specific ultrasonic features of AAMs were delineated in detail in this study. Meanwhile, the role of ultrasound in the management of AAM is discussed from different aspects. We emphasized the utilization of different ultrasound probes and colour Doppler ultrasound in the management of AAM in this article. There exist several limitations of the study. First, the number of cases with complete imaging records was limited. For further establishment of the ultrasonic features of AAMs, more typical cases are warranted. Moreover, new modalities of ultrasound imaging could be added in the further study of the disease, which might be of significance in better understanding the behaviors of AAM. Three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound was performed in a previous study, and the dimension of the lesion was fully assessed[39]. Studies about the enhancement pattern of AAM on contrast-enhanced ultrasound can assist in establishing the role of ultrasound in the management of the disease.

In conclusion, AAMs are rare benign tumours, which originate from mesenchymal tissues, and can easily be misdiagnosed as other pelvic masses. Imaging examinations, including ultrasound, CT, and MRI, are commonly used for diagnosis and follow-up. The sonographic features of AAM are relatively characteristic and helpful for differential diagnosis. Ultrasound can be of great significance for preoperative diagnosis, evaluation of tumour scope, and recurrence surveillance.

A total of eight cases of aggressive angiomyxoma (AAM) who received imaging examinations and surgical resections are reported in the article.

AAM.

Bartholin’s duct cyst, Gartner’s duct cyst, vaginal prolapse, angiomyofibroblastoma, myxoma, and myxoid sarcoma.

There is no special laboratory diagnosis for the patients.

Ultrasound, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be utilized for the evaluation of AAM. The imaging features of AAM on ultrasound and MRI are characteristic.

Scattered spindle cells with low mitotic activity and a myxoid and collagen matrix are the main constituents of the lesions. Immunohistochemistry can also be helpful.

The tumour of AAM requires a complete surgical resection. Gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist is also widely used.

Approximately 300 cases of AAMs have been reported since the first report in 1983. This article is focused on the ultrasonic features of the neoplasms.

Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE) imaging: DCE imaging is acquired after a rapid intravenous injection of gadolinium-DTPA. It can delineate the vasculature of local tissues and is helpful in evaluating vascularity. Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC): DWI is an important sequence of MRI; it measures the mobility of water molecules due to Brownian motion. The ADC is a quantitative measure reflecting this motion. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS): CEUS imaging is also obtained by injection of microbubbles, for better visualization of the anatomic structures and perfusion patterns.

The ultrasonic features of AAM are distinguished. Ultrasound as a convenient imaging method, can play an important role in the diagnosis and follow-up of the disease.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Razek AAKA, Soresi M, Stavroulopoulos A S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Steeper TA, Rosai J. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum. Report of nine cases of a distinctive type of gynecologic soft-tissue neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 1983;7:463-475. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 373] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Behranwala KA, Thomas JM. ‘Aggressive’ angiomyxoma: a distinct clinical entity. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2003;29:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dursun H, Bayazit AK, Büyükçelik M, Iskit S, Noyan A, Apbak A, Gönlüşen G, Anarat A. Aggressive angiomyxoma in a child with chronic renal failure. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21:563-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mascarenhas L, Knaggs J, Clark J, Eliot B. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis and perineum: case report and literature review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169:555-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miguez Gonzalez J, Dominguez Oronoz R, Lozano Arranz P, Calaf Forn F, Barrios Sanchez P, Garcia Jimenez A. Aggressive Angiomyxoma: Imaging Findings in 3 Cases With Clinicopathological Correlation and Review of the Literature. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015;39:914-921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Salman MC, Kuzey GM, Dogan NU, Yuce K. Aggressive angiomyxoma of vulva recurring 8 years after initial diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:485-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sutton BJ, Laudadio J. Aggressive angiomyxoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Piura B, Shaco-Levy R. Pedunculated aggressive angiomyxoma arising from the vaginal suburethral area: case report and review of literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2005;26:568-571. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Papachristou DJ, Batistatou A, Paraskevaidis E, Agnantis NJ. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vagina: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2004;25:519-521. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chihara Y, Fujimoto K, Takada S, Hirayama A, Cho M, Yoshida K, Ozono S, Hirao Y. Aggressive angiomyxoma in the scrotum expressing androgen and progesterone receptors. Int J Urol. 2003;10:672-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Morag R, Fridman E, Mor Y. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the scrotum mimicking huge hydrocele: case report and literature review. Case Rep Med. 2009;2009:157624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shah JS, Sharma S, Panda M. Aggressive angiomyxoma of maxilla: A confounding clinical condition with rare occurrence! J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2018;22:286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cakarer S, Isler SC, Keskin B, Uzun A, Kocak Berberoglu H, Keskin C. Treatment For The Large Aggressive Benign Lesions Of The Jaws. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2018;17:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bai HM, Yang JX, Huang HF, Cao DY, Chen J, Yang N, Lang JH, Shen K. Individualized managing strategies of aggressive angiomyxoma of female genital tract and pelvis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:1101-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Surabhi VR, Garg N, Frumovitz M, Bhosale P, Prasad SR, Meis JM. Aggressive angiomyxomas: a comprehensive imaging review with clinical and histopathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202:1171-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sun Y, Zhu L, Chang X, Chen J, Lang J. Clinicopathological Features and Treatment Analysis of Rare Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Female Pelvis and Perineum - a Retrospective Study. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | McCluggage WG, Patterson A, Maxwell P. Aggressive angiomyxoma of pelvic parts exhibits oestrogen and progesterone receptor positivity. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chen H, Zhao H, Xie Y, Jin M. Clinicopathological features and differential diagnosis of aggressive angiomyxoma of the female pelvis: 5 case reports and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96:e6820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wiser A, Korach J, Gotlieb WH, Fridman E, Apter S, Ben-Baruch G. Importance of accurate preoperative diagnosis in the management of aggressive angiomyxoma: report of three cases and review of the literature. Abdom Imaging. 2006;31:383-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sun NX, Li W. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: case report and literature review. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1547-1552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sereda D, Sauthier P, Hadjeres R, Funaro D. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva: a case report and review of the literature. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2009;13:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kiran G, Yancar S, Sayar H, Kiran H, Coskun A, Arikan DC. Late recurrence of aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17:85-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Idrees MT, Hoch BL, Wang BY, Unger PD. Aggressive angiomyxoma of male genital region. Report of 4 cases with immunohistochemical evaluation including hormone receptor status. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2006;10:197-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Blandamura S, Cruz J, Faure Vergara L, Machado Puerto I, Ninfo V. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a second case of metastasis with patient’s death. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:1072-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Srinivasan S, Krishnan V, Ali SZ, Chidambaranathan N. “Swirl sign” of aggressive angiomyxoma-a lesser known diagnostic sign. Clin Imaging. 2014;38:751-754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tariq R, Hasnain S, Siddiqui MT, Ahmed R. Aggressive angiomyxoma: swirled configuration on ultrasound and MR imaging. J Pak Med Assoc. 2014;64:345-348. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Jeyadevan NN, Sohaib SA, Thomas JM, Jeyarajah A, Shepherd JH, Fisher C. Imaging features of aggressive angiomyxoma. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:157-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Al-Umairi RS, Kamona A, Al-Busaidi FM. Aggressive Angiomyxoma of the Pelvis and Perineum: A Case Report and Literature Review. Oman Med J. 2016;31:456-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Brunelle S, Bertucci F, Chetaille B, Lelong B, Piana G, Sarran A. Aggressive angiomyxoma with diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and dynamic contrast enhancement: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Oncol. 2013;6:373-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ota H, Otsuki K, Ichihara M, Ishikawa T, Okai T. A case of aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2013;40:283-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Huang CC, Sheu CY, Chen TY, Yang YC. Aggressive angiomyxoma: a small palpable vulvar lesion with a huge mass in the pelvis. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17:75-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Wenig BM, Vinh TN, Smirniotopoulos JG, Fowler CB, Houston GD, Heffner DK. Aggressive psammomatoid ossifying fibromas of the sinonasal region: a clinicopathologic study of a distinct group of fibro-osseous lesions. Cancer. 1995;76:1155-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Granter SR, Nucci MR, Fletcher CD. Aggressive angiomyxoma: reappraisal of its relationship to angiomyofibroblastoma in a series of 16 cases. Histopathology. 1997;30:3-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Güngör T, Zengeroglu S, Kaleli A, Kuzey GM. Aggressive angiomyxoma of the vulva and vagina. A common problem: misdiagnosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;112:114-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Petscavage-Thomas JM, Walker EA, Logie CI, Clarke LE, Duryea DM, Murphey MD. Soft-tissue myxomatous lesions: review of salient imaging features with pathologic comparison. Radiographics. 2014;34:964-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Wolf B, Horn LC, Handzel R, Einenkel J. Ultrasound plays a key role in imaging and management of genital angiomyofibroblastoma: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2015;9:248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kim SW, Lee JH, Han JK, Jeon S. Angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva: sonographic and computed tomographic findings with pathologic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 2009;28:1417-1420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Nagai K, Aadachi K, Saito H. Huge pedunculated angiomyofibroblastoma of the vulva. Int J Clin Oncol. 2010;15:201-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Foust-Wright C, Allen A, Shobeiri SA. Periurethral aggressive angiomyxoma: a case report. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:877-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |