Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.781

Peer-review started: August 21, 2018

First decision: October 11, 2018

Revised: October 21, 2018

Accepted: October 22, 2018

Article in press: October 22, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 102 Days and 21.4 Hours

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare, hemorrhagic autoimmune disease, whose pathogenesis involves reduced coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) activity related to the appearance of inhibitors against FVIII. Common etiological factors include autoimmune diseases, malignancy, and pregnancy. We report two cases of AHA in solid cancer. The first case is a 63-year-old man who developed peritoneal and intestinal bleeding after gastrectomy for gastric cancer. He was diagnosed with AHA, and was treated with prednisone, followed by cyclophosphamide. In the second case, a 68-year-old man developed a subcutaneous hemorrhage. He was diagnosed with AHA in hepatocellular carcinoma on CT imaging, and treated with rituximab alone. Hemostasis was achieved for both patients without bypassing agents as the amount of inhibitors was reduced and eradicated. However, both patients died within 1 year due to cancer progression. Successful treatment for AHA in solid cancer can be difficult because treatment of the underlying malignancy is also required.

Core tip: Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a rare hemorrhagic disease usually affecting the elderly, involving reduced coagulation factor VIII activity. Malignancies are reported to occur in association with 10%-15% of patients with AHA. We report two cases of AHA in solid cancer, namely, gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. Hemostasis was fully achieved owing to eradication of inhibitor against factor VIII, however, both patients died within 1 year due to cancer progression. Successful treatment for AHA in solid cancer can be difficult because not only active hemorrhage management and inhibitor eradication but also treatment of the underlying malignancy is required.

- Citation: Saito M, Ogasawara R, Izumiyama K, Mori A, Kondo T, Tanaka M, Morioka M, Ieko M. Acquired hemophilia A in solid cancer: Two case reports and review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 781-785

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/781.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.781

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) is a hemorrhagic disease with a decrease in coagulation factor VIII (FVIII) activity due to the appearance of autoantibodies (inhibitors) against FVIII[1,2]. The breakdown of the immune control mechanism is speculated to cause this disease[1]. AHA is very rare, and the annual incidence is about 1.48/million/year[2]. Elderly patients (age ≥ 60 years) account for over 80%[2]. In the majority of patients with AHA, hemorrhage is sudden and spontaneous, although it occurs in approximately 25% of patients after trauma or invasive procedures[3].

Approximately 50% of patients have no underlying AHA-associated condition. Common etiological factors include autoimmune diseases (14.1%), malignancy (11.5%), and pregnancy (8.9%)[4]. The most common cause of solid cancers in AHA is prostate cancer, followed by lung cancer[5,6]. A recent study demonstrated that malignancy at baseline was associated with reduced overall survival for patients with AHA[7]. In addition, a systematic review described a large number of AHA patients with cancer[8]. However, evidence to confirm AHA in association with solid cancers needs to be obtained in more patients. In this study, we performed a retrospective analysis of the clinical characteristics of two AHA patients with solid cancers, namely, gastric cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) at our institution.

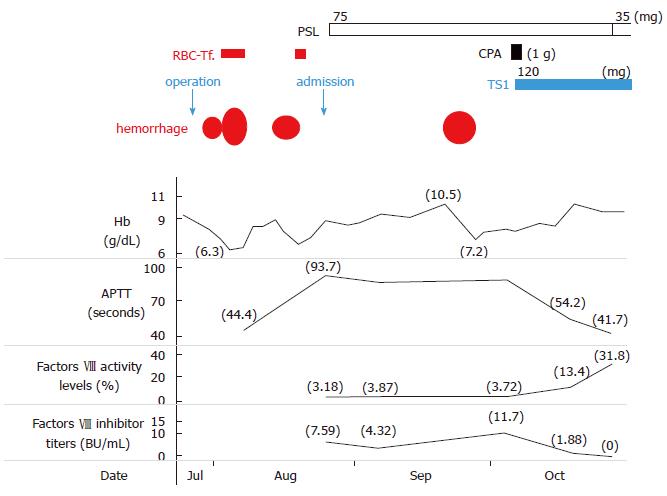

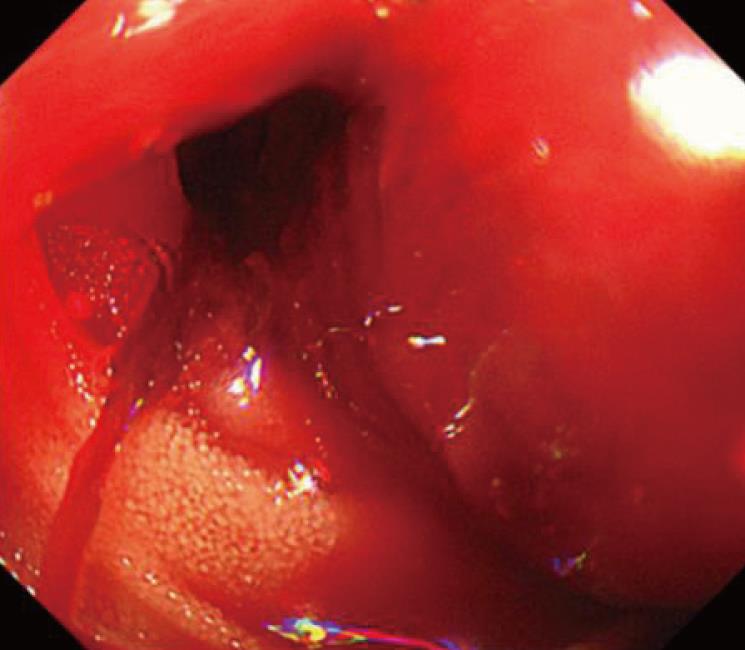

A 63-year-old man had been diagnosed with gastric cancer and had undergone a gastrectomy at his nearby hospital. Bleeding within the intraperitoneal drainage tube was observed 5 d after surgery. Intraperitoneal cytology identified gastric cancer cells and a diagnosis of stage IV gastric cancer was confirmed. He developed hematemesis and melena 2 d following the removal of the drainage tube. His anemia worsened and his hemoglobin (Hb) level reached 6.3 g/dL, requiring red blood cell (RBC) transfusions for 5 d consecutively. Endoscopic examination revealed intestinal bleeding from the site of the anastomosis (Figure 2), and endoscopic hemostasis was performed. Subcutaneous hemorrhage became apparent in both lower extremities over several days. Transfusion with a total of 7 units of packed RBC was performed. The activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was prolonged to 74.2 s compared to 23.1 s measured preoperatively, and the patient was transferred to our hospital.

On admission, the patient presented with anemia, an Hb level of 9.0 g/dL and a prolonged APTT of 93.7 s. FVIII activity was reduced to 3.18%, the inhibitor titer was 7.59 BU/mL, and he was diagnosed with AHA. Prednisone (PSL 1 mg/kg per day) and tranexamic acid were administered. Although the patient had developed an intramuscular hematoma in the right iliacus muscle approximately 1 mo after treatment, bypassing agents had not been administered because the hemorrhage was not persistent. As the inhibitor titer had increased to 11.7 BU/mL, 1 g of cyclophosphamide (CPA) was additionally administered and chemotherapy for gastric cancer with TS1 (tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil) was initiated. The inhibitors were eradicated, and the patient was discharged 9 wk after treatment for AHA. Because the patient remained in remission for AHA, the PSL dose was reduced and stopped. Treatment for gastric cancer was administered repeatedly; however, the patient died 9 mo after gastrectomy due to carcinomatous peritonitis.

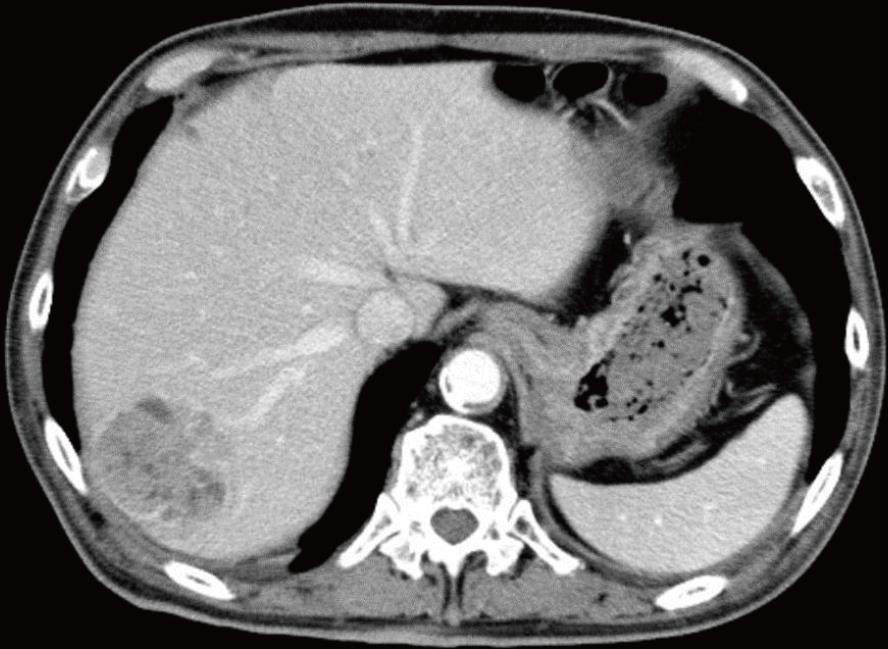

The second patient was a 68-year-old man with a history of cerebral infarction who had developed dementia (ECOG performance status, 3-4), in addition to arteriosclerosis obliterans, diabetes mellitus (DM), and hypertension. He had been taking a small amount (5 mg) of PSL for nephrotic syndrome. He was admitted to the local hospital having developed a non-traumatic subcutaneous hemorrhage in his right forearm. An abdominal computed tomography scan revealed hepatocellular carcinoma (file size 5.5 cm in diameter) (Figure 3). The anemia had progressed and his Hb levels had reduced from 12.7 to 8.1 g/dL, and 1 unit of packed RBC had been transfused. The APTT was prolonged to between 70 and 80 s, and he was transferred to our hospital.

On admission, the patient had anemia lasting, with an Hb of 7.8 g/dL and a prolonged APTT of 94.0 s. FVIII activity was reduced to 3.1%, the inhibitor titer had increased to 57.1 BU/mL, and he was diagnosed with AHA. Although his liver function tests were normal, he tested positive for hepatitis C virus antibodies, and the values of alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence-II were significantly higher at 1862 ng/mL and 210 mAU/mL, respectively. His anemia had worsened (Hb level, 6.8 g/dL), and 1 unit of packed RBC was transfused. Bypassing agents were not used as the bleeding was not considered to be severe at that time. In addition to continuing PSL administration (5 mg/d), rituximab (RTX 375 mg/m2) was administered 5 times every week in order to eradicate the inhibitors without eliciting side effects. As a result, the inhibitor titer was reduced to 3.5 BU/mL after 3 wk and hemostasis was achieved. The patient was transferred back to his previous hospital to continue treatment for HCC. At this hospital, eradication of the inhibitors was confirmed approximately 1 mo after RTX treatment had terminated. Although transcatheter arterial chemoembolization was performed for HCC, the treatment was not effective, and the HCC continued to progress aggressively. The patient died at the hospice 7 mo after the HCC diagnosis.

Control failure of Treg cell line against autoimmune response to FVIII is considered to be one of the onset factors of AHA[9]. More intense antibody responses, that is, higher inhibitor titers (10 BU or more) to FVIII correlated with a predominance of Th2-driven subclasses IgG4[10].

Malignancies have been reported to occur in 11.5% of patients with AHA[4]. This pathological condition can be attributed to an imbalance in the immune system associated with the onset of solid cancer. However, the true causality and the underlying mechanism by which cancer cells induce autoantibodies to FVIII have not been elucidated yet[8]. Iatrogenic bleeding may be the initial sign in AHA patients[11]. In case 1, since the APTT before gastrectomy was normal, surgical procedure may be a trigger for the development of an acquired inhibitor against FVIII.

Regardless of the presence or absence of underlying disease, the treatment for AHA is divided into hemostatic therapy for hemorrhage[4] and immunotherapy aimed at eradicating inhibitors[12]. Bypass hemostatic agents, recombinant activated factor VII and activated prothrombin complex concentrate, are considered to the first-line approach for the treatment of bleeding episodes[4,13]. In the study of the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH 2), 144 of the 482 AHA patients (30%), especially for “non-severe” patients, hemostatic treatment was not required[4]. The two patients in our study did not develop life-threatening bleeding after they were transferred to our hospital. Therefore, immunological treatments were administered instead of bypassing agents to achieve hemostasis through reducing the inhibitor titer against FVIII. The EACH2 study demonstrated that among the immunological treatments for AHA, the combination of PSL and CPA was more effective than PSL alone, with remission rates of 80% and 58%, respectively[12]. In our first patient, PSL alone was not effective, but the combination of PSL and CPA was effective. Our second patient had DM and was almost bedridden, and could not use either original PSL (1 mg/kg day) or CPA because he was considered to have a high risk of developing fatal infectious diseases. According to Japanese and Italian guidelines[14,15], RTX alone was selected, which is suggested as an alternative treatment, and our patient was successfully treated.

In the recent review based on the histories of 105 cases of AHA in cancers, prostate (25.3%) and lung (15.8%) cancer were more frequent, followed by colon cancer (9.5%)[8]. There were 3 cases of gastric cancer[16-18] and 2 cases of HCC[19,20]. Another case report for AHA with HCC has also been published[21]. Compared with the patients with idiopathic AHA, patients with cancer are more likely to show recurrent bleeding and are less likely to achieve a complete response with eradication of the inhibitors[8]. As with our two patients, gastric cancer and HCC were both identified as advanced cancers in these studies and patients generally had a poor prognosis. Regarding hemostasis, AHA in our patients was successfully treated, however, both patients died of cancer within 1 year. As noted by Casadiego-Peña et al[22], in the case of AHA with cancer, it is recommended to combine immunological treatment to eradicate the inhibitor with therapy for the malignancy. In our patients, cancer progression may not have occurred due to immunosuppression resulting from the administration of immunological treatments, but it is more likely that the cancers were already highly advanced at the time of AHA onset.

In conclusion, AHA remission was achieved in both patients despite cancer progression until their deaths. Besides hemostatic therapy and immunological treatments, successful treatment of AHA patients with cancer requires the concurrent treatment of the underlying malignancy. As opposed to hematological malignancies for which chemotherapy is often effective, solid cancers in AHA patients are typically detected at advanced stages. Thus, these patients are likely to have a poor prognosis.

We would like to thank Doctor Takuro Machida (Sapporo Century Hospital) and Doctor Hajime Sakai (Teine Keijinkai Hospital) for your help in following our two cases reported here.

60s two Japanese men with solid cancer [one is gastric cancer, the other is hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)] had a marked bleeding tendency.

Progressed anemia due to severe hemorrhage, requiring blood transfusion.

Hemorrhagic disease, such as immune thrombocytopenia or disseminated intravascular coagulation.

In both patients, hemoglobin level reached < 7 g/dL, prolonged APTT of 94 s, and FVIII activity was reduced to 3.1%. The inhibitor titer was 7.59 and 57.1 BU/mL respectively, compatible with acquired hemophilia A (AHA). In the second patients, hepatitis C virus antibodies were positive and the levels of alpha-fetoprotein and protein induced by vitamin K absence-II were 1862 ng/mL and 210 mAU/mL, respectively.

Endoscopic examination in the first case revealed intestinal bleeding from the site of the anastomosis. Abdominal computed tomography scan in the second patients revealed HCC (5.5 cm in diameter).

In the first case, resected stomach and intraperitoneal cytology identified gastric cancer.

Immunological treatments (prednisone and cyclophosphamide in case 1, and rituximab alone in case 2) were administered instead of bypassing agents. Oral tegafur/gimeracil/oteracil was administered in case 1, and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization was performed in case 2.

Recently, a systematic review described a large number of AHA patients with cancer.

AHA patients with cancer are more likely to exhibit recurrent hemorrhage and are less likely to achieve a complete response with eradication of the neutralizing autoantibodies.

Besides hemostatic therapy and immunological treatments, successful treatment of AHA patients with cancer requires the concurrent treatment of the underlying malignancy.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Chedid MF, Niu ZS, Tiberio GAM S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Delgado J, Jimenez-Yuste V, Hernandez-Navarro F, Villar A. Acquired haemophilia: review and meta-analysis focused on therapy and prognostic factors. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:21-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Collins PW, Hirsch S, Baglin TP, Dolan G, Hanley J, Makris M, Keeling DM, Liesner R, Brown SA, Hay CR; UK Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Acquired hemophilia A in the United Kingdom: a 2-year national surveillance study by the United Kingdom Haemophilia Centre Doctors' Organisation. Blood. 2007;109:1870-1877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 453] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baudo F, Mostarda G, de Cataldo F. Acquired factor VIII and factor IX inhibitors: survey of the Italian haemophila centers (AICE). Haematologica. 2003;88 Suppl 12:S93-99 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285180247. |

| 4. | Baudo F, Collins P, Huth-Kühne A, Lévesque H, Marco P, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, Tengborn L, Knoebl P; EACH2 registry contributors. Management of bleeding in acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia (EACH2) Registry. Blood. 2012;120:39-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Reeves BN, Key NS. Acquired hemophilia in malignancy. Thromb Res. 2012;129 Suppl 1:S66-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sallah S, Wan JY. Inhibitors against factor VIII in patients with cancer. Analysis of 41 patients. Cancer. 2001;91:1067-1074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tiede A, Klamroth R, Scharf RE, Trappe RU, Holstein K, Huth-Kühne A, Gottstein S, Geisen U, Schenk J, Scholz U. Prognostic factors for remission of and survival in acquired hemophilia A (AHA): results from the GTH-AH 01/2010 study. Blood. 2015;125:1091-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Napolitano M, Siragusa S, Mancuso S, Kessler CM. Acquired haemophilia in cancer: A systematic and critical literature review. Haemophilia. 2018;24:43-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lacroix-Desmazes S, Navarrete AM, André S, Bayry J, Kaveri SV, Dasgupta S. Dynamics of factor VIII interactions determine its immunologic fate in hemophilia A. Blood. 2008;112:240-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Reding MT, Lei S, Lei H, Green D, Gill J, Conti-Fine BM. Distribution of Th1- and Th2-induced anti-factor VIII IgG subclasses in congenital and acquired hemophilia patients. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:568-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Boggio LN, Green D. Acquired hemophilia. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2001;5:389-404; quiz following 431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Collins P, Baudo F, Knoebl P, Lévesque H, Nemes L, Pellegrini F, Marco P, Tengborn L, Huth-Kühne A; EACH2 registry collaborators. Immunosuppression for acquired hemophilia A: results from the European Acquired Haemophilia Registry (EACH2). Blood. 2012;120:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 240] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saito M, Kanaya M, Izumiyama K, Mori A, Irie T, Tanaka M, Morioka M, Ieko M. Treatment of bleeding in acquired hemophilia A with the proper administration of recombinant activated factor VII: single-center study of 7 cases. Int J Gen Med. 2016;9:393-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sakai M, Amano K, Ogawa K, Takami A, Tokugawa T, Nogami K, Hato T, Fujii T, Matsumoto I, Matsumoto T. Guidelines for the management of acquired hemophilia A: 2017 revision. Nihon Kessen Shiketsu Gakkai Zasshi. 2017;28:715-747. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Franchini M, Castaman G, Coppola A, Santoro C, Zanon E, Di Minno G, Morfini M, Santagostino E, Rocino A; AICE Working Group. Acquired inhibitors of clotting factors: AICE recommendations for diagnosis and management. Blood Transfus. 2015;13:498-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hayashi T, Morishita E, Asakura H, Nakao S. Two cases of acquired hemophilia A in elderly patients. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2010;47:329-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sallah S, Singh P, Hanrahan LR. Antibodies against factor VIII in patients with solid tumors: successful treatment of cancer may suppress inhibitor formation. Haemostasis. 1998;28:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Harada Y, Iwai M, Miyoshi M, Ueda Y, Mitsufuji S, Seiki K, Harada M, Kashima K. Life-threatening hemorrhage in a patient with gastric cancer and acquired hemophilia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1372-1373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Neilson RF, Walker ID, Robertson M. Factor VIII inhibitor associated with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Lab Haematol. 1993;15:145-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Croft J, Sahu S. Acquired haemophilia A in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Franco-Moreno AI, Santero-García M, Cabezón-Gutiérrez L, Martín-Díaz RM, García-Navarro MJ. Acquired hemophilia A in a patient with hepatocellular carcinoma: a case report and literature review. Ann Hematol. 2016;95:2099-2100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Casadiego-Peña C, González-Motta A, Perilla OG, Gomez PD, Enciso LJ. Acquired Hemophilia Secondary to Soft-tissue Sarcoma: Case Report from a Latin American Hospital and Literature Review. Cureus. 2018;10:e2621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |