Published online Nov 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.776

Peer-review started: June 22, 2018

First decision: August 1, 2018

Revised: August 18, 2018

Accepted: October 8, 2018

Article in press: October 8, 2018

Published online: November 26, 2018

Processing time: 157 Days and 14.8 Hours

A 19-year-old female was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis when she presented with persistent melena, and has been treated with 5-aminosalicylic acid for 4 years, with additional azathioprine for 2 years at our hospital. The patient experienced high-grade fevers, chills, and cough five d prior to presenting to the outpatient unit. At first, the patient was suspected to have developed neutropenic fever; however, she was diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (EB-VAHS) upon fulfilling the diagnostic criteria after bone marrow aspiration. When patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with immunomodulators, such as thiopurine preparations, develop fever, EB-VAHS should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Core tip: A 19-year-old female was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis, and has been receiving treatment with 5-aminosalicylic acid for 4 years, with additional azathioprine for 2 years. The patient experienced high-grade fever five d prior to presenting to the outpatient unit. She was diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS). VAHS is one of the rare and life-threatening pathophysiological conditions induced by thiopurine treatment. In such cases, early diagnosis is necessary, along with management of therapy, and related complications. When patients with inflammatory bowel disease, treated with immunomodulators such as thiopurine preparations, demonstrate high fever, VAHS should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

- Citation: Miyaguchi K, Yamaoka M, Tsuzuki Y, Ashitani K, Ohgo H, Miyagawa Y, Ishizawa K, Kayano H, Nakamoto H, Imaeda H. Epstein–Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome in a patient with ulcerative colitis during treatment with azathioprine: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(14): 776-780

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i14/776.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i14.776

Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome (VAHS) is an extremely rare and life-threatening complication, sometimes induced by viral infection. It is characterized by high-grade fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). The syndrome is diagnosed by the presence of histiocytosis in the lymphoreticular network (i.e., the bone marrow)[1]. The etiological agent is a virus, such as Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes zoster virus, human herpesvirus 6, rubella, measles virus, or influenza virus. Among them, Epstein-Barr VAHS (EB-VAHS) tends to be severe[2].

Thiopurine formulations are reported to be effective for the long-term remission of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[3]. However, side effects such as myelosuppression, hepatic dysfunction, pancreatitis, hair loss, and gastrointestinal symptoms are observed in approximately 3% of patients. In particular, myelosuppression is reported to occur within 2 mo of drug administration[4]. A recent report also suggested that patients with IBD receiving thiopurine treatment are at an increased risk of developing lymphoproliferative disorders[5]. Therefore, it is necessary to consider the adverse effects of thiopurine treatment when fever, leukopenia, hepatic dysfunction, etc. are observed.

Here we report a case of EB-VAHS during the treatment of ulcerative colitis with drugs including azathioprine (AZA).

A 19-year-old female with frequent bloody stools presented to our hospital in 2017. She was diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (pancolitis) by total colonoscopy in 2013. The patient was treated with 3600 mg/d of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) and went into remission. She experienced recurrence of bloody stools in 2015, and was treated with 50 mg/d of AZA. Although AZA treatment was initiated, the patient occasionally experienced bloody stools and prednisolone (PSL) was administered, after which her condition improved. The AZA dose was increased to 100 mg/d in 2016. Although she occasionally experienced bloody stools, her symptoms were relieved by additional administration of 5-ASA suppositories.

The patient was admitted to our hospital with fever, ocular pains, chills, and cough for 5 d prior to admission in 2017. Her neutrophil count had decreased to 589/μL, and leukocyte reduction was not evident in blood results 2 d before her symptoms started. The patient developed a fever of 38.8 °C, but showed no abnormalities in the chest and abdomen, with no observed cervical lymph node swelling.

The patient presented with fever, along with mild anemia [hemoglobin (Hb), 11.1 g/dL], mild thrombocytopenia (13.0 × 104/μL), mildly elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (1.32 mg/dL), and neutropenia [white blood cell (WBC), 940/μL; neutrophils, 589/μL].

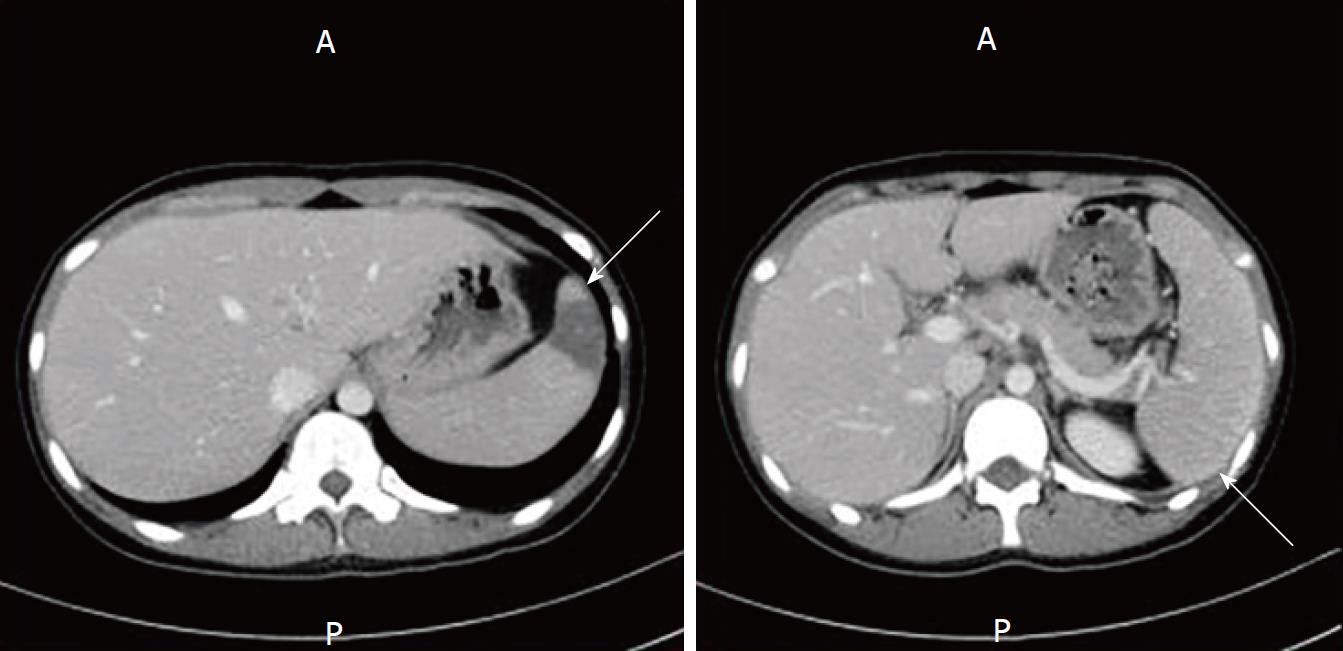

Colonoscopy revealed that the mucosa was mildly inflamed only on the left side of the colon; the endoscopic subscore was Mayo score 1 (Figure 1). The patient was treated with 2 g/d of cefepime and granulocyte-colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), but her WBC and neutrophil counts improved only to 2650/μL, and 1661/μL, respectively. The fever persisted, and her condition was complicated by the appearance of right cervical lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly and splenic infarction were observed via thoracoabdominal contrast computed tomography scanning (Figure 2). In addition, liver dysfunction (Aspartate transaminase, 225 IU/L; alanine aminotransferase, 200 IU/L), and increases in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) (589 IU/L), ferritin (740 ng/mL), and soluble interleukin 2 receptor (sIL-2R) (5210 IU/mL) were observed on biochemical examination. Aggravated anemia (Hb, 9.4 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (8 × 104/μL), and the appearance of atypical lymphocytes (Aty-Lym, 2%) were also observed on peripheral blood examination. Bone marrow smear examination showed an increase in foamy macrophages, and blood cell phagocytosis (Figure 3), but no chromosomal abnormalities. Furthermore, antibody test results, were suggestive of primary acute EBV infection, as follows: EB immunoglobulin M (EB-IgM) positive, EB-IgG positive, EB nuclear antigen (EBNA) negative, and EB deoxyribonucleic acid (EB-DNA) positive (1.0 × 104 copies/mL). CMV IgG was negative. The diagnostic criteria for VAHS are as follows: (1) blood cell phagocytosis, myelocyte phagocytosis; (2) elevated ferritin; and (3) elevated sIL-2R levels (≥ 2400 IU/mL). Taken together, the patient was diagnosed with EB-VAHS. The patient was treated with steroid pulse therapy (methylprednisolone 1000 mg/d for 3 d), and her symptoms and examination findings improved. After pulse therapy, PSL was tapered gradually from 60 mg/d. The follow-up lab examination data after improvement from VAHS was as follows: WBC 6720/μL, Hb 13.4 g/dL, platelet 16.2 × 104, LDH 175U/L, Aty-Lym negative, EB-virus capsid antigen (EB-VCA) IgM negative, EB-VCA IgG positive (× 40), EBNA 1.3C.I, EB-DNA positive, ferritin 18 ng/mL, sIL-2R 290 IU/mL. The patient was discharged after a couple of weeks and was followed-up in the outpatient unit.

The initial diagnosis was neutropenic fever accompanied by bone marrow suppression, probably due to AZA administration. However, bone marrow suppression by AZA often occurs within 2 mo of initiation, however here, 1 year had passed since AZA was increased from 50 mg to 100 mg before bone marrow suppression was evident. In addition, the patient showed only minor improvement to white blood cell, and neutrophil counts, while fever persisted during G-CSF treatment. The diagnosis of VAHS was made based on symptoms such as cervical lymph node swelling, splenomegaly, hepatic dysfunction, pancytopenia, elevated LDH, elevated ferritin, elevated sIL-2R, and the appearance of Aty-Lym. However, a bone marrow biopsy was required to make a definite diagnosis. Although the mechanism of VAHS is yet to be completely elucidated, it is reported that activation of T-cells, as well as macrophage proliferation, and the production of cytokines triggered by viral infection such as EBV are responsible for characteristic symptoms like high-grade fever, hepatosplenomegaly, pancytopenia, and DIC[1]. These symptoms could be related to disease severity[6]. Therefore, when VAHS is strongly suspected by clinical findings, it is recommended that treatment should be initiated before fulfilling the diagnostic criteria[7]. The treatment for VAHS is divided into four steps[1]. First, steroid such as cyclosporine and etoposide are administered to control the resultant hypercytokinemia, and plasma exchange may be considered if hypercytokinemia is resistant to initial treatment. Second, if there is a virus-specific treatment, the etiological virus should be targeted. Third, if the virus is refractory to treatment, removal of virus-infected lymphocytes by CHOP therapy (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone), according to treatment for malignant lymphoma, should be considered. Fourth, supportive therapy for secondary infection, DIC, and central nervous symptom and hepatic disorders may be considered.

Eight cases of CMV infection and five of EBV infection have been reported to be VAHS cases after AZA administration during ulcerative colitis treatment[8-15]; however, the etiological virus is unknown in most cases. There have also been reports that it is unknown whether the syndrome is caused due to acute or chronic infection, however, most cases are positive for both IgM and IgG. Therefore, the pathology of VAHS is thought to be mainly caused by reactivation of chronic viral infection, although VAHS could also occur due to acute viral infection. In the present case, EB-IgM was positive and EBNA was negative; therefore, this case of VAHS was caused by primary acute infection. It is difficult to diagnose VAHS in many cases, and the syndrome occurrs during remission rather than immediately after AZA administration. Prognosis greatly differs between EBV-, and non-EBV-associated cases and 70% of non-EBV-associated cases are reported to be cured only by supportive therapy[2]. In contrast, in EBV-associated cases, a more severe course was observed and 4 of 16 patients with VAHS died during IBD therapy[9,12,14,15]. Old age, DIC, elevated ferritin, thrombocytopenia, anemia, jaundice, and chromosomal abnormalities are frequently observed, and are poor prognostic factors[15]. Some studies reported chromosomal abnormalities after chromosome analysis of bone marrow cells revealed an abnormal karyotype, although none were specific. In the present case, no DIC or chromosomal abnormalities were observed, and the clinical course was well controlled. The factors responsible for VAHS in patients with IBD are as follows: (1) mucosal immune systems, such as immune tolerance in the intestinal tract, are destroyed due to IBD; (2) immunomodulating drug therapy increases susceptibility too many infections including opportunistic infections; (3) once viral infection occurs, the pathogen-exclusion mechanism does not function well, and the immune response loses efficacy.

Therefore, long-term AZA administration might trigger EB infection and induce VAHS. However, to prove this theory, one needs to demonstrate an immunosuppressive state at the time of EB infection, and the subsequent exponential cytokine storm after EB infection, leading to VAHS.

VAHS is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication of EBV infection. Although this syndrome is also rare in patients with IBD treated with thiopurine preparations, administration of immunosuppressants or immunomodulators may increase the risk of viral infection.

Thererfore, when high-grade fever, cytopenia, and elevated liver enzyme, ferritin, and LDH levels are observed in patients with ulcerative colitis treated with thiopurine preparations, VAHS should be considered in the differential diagnosis if CMV or EBV infection is confirmed. In addition, it should be remembered that hemophagocytosis is a fatal disease and caution should always be implemented to avoid this fatal consequences.

19-year-old female presented high-grade fevers, chills, and cough five d prior to presenting to the outpatient unit.

Patient was diagnosed with Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome upon fulfilling the diagnostic criteria after bone marrow aspiration, during the treatment with azathioprine (AZA) for UC.

Febrile neutropenia.

Pancyopenia (white blood cell, 2650/μL; hemoglobin, 9.4 g/dL; platelet, 8.0 × 104); lactate dehydrogenase, 589 U/L; atypical lymphocytes, 2.0%; Epstein-Barr virus capsid antigen immunoglobulin M (EB-VCA-IgM), positive; EB-VCA-IgG, positive; EB nuclear antigen, negative; EB deoxyribonucleic acid, positive (1.0 × 104 copies/mL); blood cell phagocytosis; myelocyte phagocytosis; ferritin elevation; and elevated soluble interleukin 2 receptor (≥ 2400 IU/mL).

Contrast computed tomography showed spleen swelling and spleen infarction.

Bone marrow examination confirmed blood cell phagocytosis.

Steroid pulse therapy and post-steroid therapy.

A case report by N’guyen et al[11] suggests that EBV-specific clinical and virological management should be considered when treating a patient with IBD with AZA.

VAHS is a rare pathophysiological condition induced by thiopurine treatment for IBD, caused by excessive lymphocytic cytokine production during viral infection.

VAHS should be included in the differential diagnosis during thiopurine treatment for IBD.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: This manuscript has completed the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Yuksel I, Khoury T, Pham PTT S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, Khamashta MA, Bosch X. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet. 2014;383:1503-1516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 788] [Cited by in RCA: 960] [Article Influence: 87.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fisman DN. Hemophagocytic syndromes and infection. Emerg Infect Dis. 2000;6:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 354] [Cited by in RCA: 365] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Timmer A, McDonald JW, Tsoulis DJ, Macdonald JK. Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD000478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lewis JD, Abramson O, Pascua M, Liu L, Asakura LM, Velayos FS, Hutfless SM, Alison JE, Herrinton LJ. Timing of myelosuppression during thiopurine therapy for inflammatory bowel disease: implications for monitoring recommendations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1195-1201; quiz 1141-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Beaugerie L, Brousse N, Bouvier AM, Colombel JF, Lémann M, Cosnes J, Hébuterne X, Cortot A, Bouhnik Y, Gendre JP. Lymphoproliferative disorders in patients receiving thiopurines for inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1617-1625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in RCA: 805] [Article Influence: 50.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kawaguchi H, Miyashita T, Herbst H, Niedobitek G, Asada M, Tsuchida M, Hanada R, Kinoshita A, Sakurai M, Kobayashi N. Epstein-Barr virus-infected T lymphocytes in Epstein-Barr virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:1444-1450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Filipovich AH. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2009;127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Posthuma EF, Westendorp RG, van der Sluys Veer A, Kluin-Nelemans JC, Kluin PM, Lamers CB. Fatal infectious mononucleosis: a severe complication in the treatment of Crohn’s disease with azathioprine. Gut. 1995;36:311-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sijpkens YW, Allaart CF, Thompson J, van’t Wout J, Kluin PM, den Ottolander GJ, Bieger R. Fever and progressive pancytopenia in a 20-year-old woman with Crohn’s disease. Ann Hematol. 1996;72:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Serrate C, Silva-Moreno M, Dartigues P, Poujol-Robert A, Sokol H, Gorin NC, Coppo P. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferation awareness in hemophagocytic syndrome complicating thiopurine treatment for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1449-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | N’guyen Y, Andreoletti L, Patey M, Lecoq-Lafon C, Cornillet P, Léon A, Jaussaud R, Fieschi C, Strady C. Fatal Epstein-Barr virus primo infection in a 25-year-old man treated with azathioprine for Crohn’s disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:1252-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chauveau E, Terrier F, Casassus-Buihle D, Moncoucy X, Oddes B. Macrophage activation syndrome after treatment with infliximab for fistulated Crohn’s disease. Presse Med. 2005;34:583-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Siegel CA, Bensen SP, Ely P. Should rare complications of treatment influence decision-making in ulcerative colitis? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Koketsu S, Watanabe T, Hori N, Umetani N, Takazawa Y, Nagawa H. Hemophagocytic syndrome caused by fulminant ulcerative colitis and cytomegalovirus infection: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1250-1253; discussion 1253-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Imashuku S. Advances in the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Int J Hematol. 2000;72:1-11. [PubMed] |