Published online Nov 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.632

Peer-review started: July 6, 2018

First decision: August 25, 2018

Revised: August 31, 2018

Accepted: October 8, 2018

Article in press: October 9, 2018

Published online: November 6, 2018

Processing time: 124 Days and 1.8 Hours

To prove that tattooing using indocyanine green (ICG) is feasible in laparoscopic surgery for a colon tumor.

From January 2012 to December 2016, all patients who underwent laparoscopic colonic surgery were retrospectively screened, and 1010 patients with colorectal neoplasms were included. Their lesions were tattooed with ICG the day before the operation. The tattooed group (TG) included 114 patients, and the non-tattooed group (NTG) was selected by propensity score matching of subjects based on age, sex, tumor staging, and operation method (n = 228). In total, 342 patients were enrolled. Between the groups, the changes in [Delta (Δ), preoperative-postoperative] the hemoglobin and albumin levels, operation time, hospital stay, oral ingestion period, transfusion, and perioperative complications were compared.

Preoperative TG had a shorter operation time (174.76 ± 51.6 min vs 192.63 ± 59.9 min, P < 0.01), hospital stay (9.55 ± 3.36 d vs 11.42 ± 8.23 d, P < 0.01), and post-operative oral ingestion period (1.58 ± 0.96 d vs 2.81 ± 1.90 d, P < 0.01). The Δ hemoglobin (0.78 ± 0.76 g/dL vs 2.2 ± 1.18 g/dL, P < 0.01) and Δ albumin (0.41 ± 0.44 g/dL vs 1.08 ± 0.39 g/dL, P < 0.01) levels were lower in the TG. On comparison of patients in the “N0” and “N1 or N2” groups, the N0 colon cancer group had a better operation time, length of hospital stay, oral ingestion period, Δ hemoglobin, and Δ albumin results than those of the N1 or N2 group. The operation methods affected the results, and laparoscopic anterior resection (LAR) showed similar results. However, for left and right hemicolectomy, both groups showed no difference in operation time or hospital stay.

Preoperative tattooing with ICG is useful for laparoscopic colectomy, especially in the N0 colon cancer group and LAR.

Core tip: As minimally invasive surgery becomes the main trend, endoscopic tattooing of colonic lesions has become important. Colonoscopic tattooing using indocyanine green (ICG) was performed in this study, resulting in a reduction in the operation time, blood loss, and the number of hospital days in patients in the N0 group. Multivariate analysis was conducted. There was strong evidence that after controlling for other variables, the tattooing procedure using ICG was associated with reduced blood loss and post-operative bowel recovery. Thus, colonoscopic tattooing using ICG is helpful in laparoscopic colectomy.

- Citation: Park JH, Moon HS, Kwon IS, Yun GY, Lee SH, Park DH, Kim JS, Kang SH, Lee ES, Kim SH, Sung JK, Lee BS, Jeong HY. Usefulness of colonic tattooing using indocyanine green in patients with colorectal tumors. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(13): 632-640

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i13/632.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.632

Locating tumors is key for appropriate and accurate treatment. However, this is often challenging, especially when the tumor size is small or the tumor is on a movable part of the colon. Minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery has become mainstream, as laparoscopic surgery has been reported to have advantages over open surgery. Preoperative endoscopic tattooing helps to find lesions and prevents resection of the wrong site[1], especially in limited operating fields of vision. In addition, the tattooing procedure provides other benefits, such as decreased operation time, reduced operative complications, and decreased blood loss. To date, few studies have reported the outcomes of tattooing with indocyanine green (ICG) dye[2-4]. Furthermore, there are no studies comparing differences in tattooed and non-tattooed groups using ICG with regard to staging and surgical methods. Because the surgical procedure and time taken for lymphadenectomy may vary from person to person, accurate results can be obtained through classification according to the surgical procedure and staging based on non-lymph node invasion group (Stage 0 and 0, I, IIa, IIb, IIc) or lymph node invasion group (IIIa, IIIb, IIIc). The aim of this study is to prove the usefulness of colonic tattooing using ICG and to demonstrate its usefulness in groups that are classified according to stage and type of laparoscopic surgery.

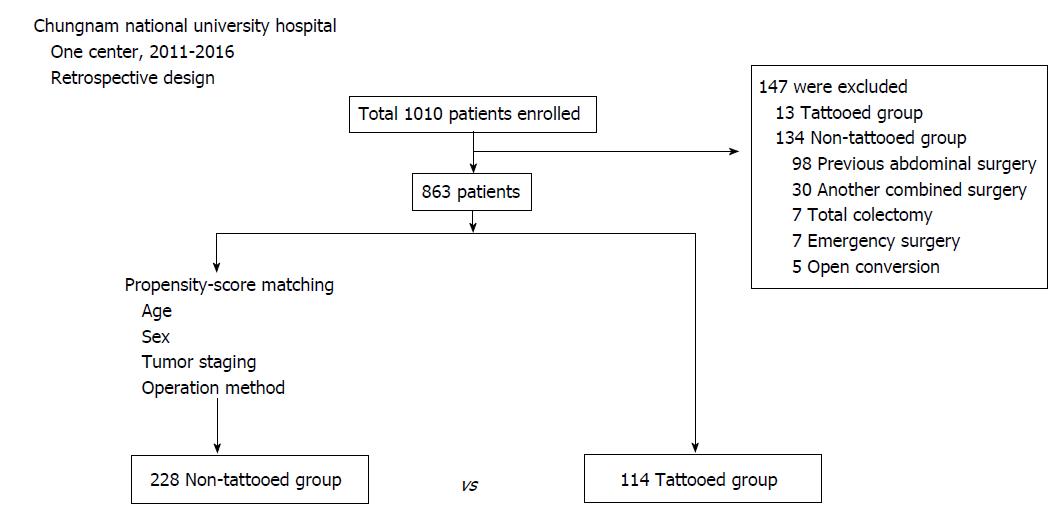

This study enrolled all patients who had undergone laparoscopic colonic surgery at Chungnam National University Hospital from January 2012 to December 2016. A total of 1010 patients with colorectal neoplasms were enrolled. Patients who were 18 years or older with histologically confirmed or endoscopically suspected colon tumors and scheduled for laparoscopic colon surgery were included. Tattooing was deemed necessary for the patient at the discretion of the surgeon, and if deemed necessary, the patient was referred to the Internal Medicine Department of the Division of Gastroenterology for the procedure. Confounding factors that would interfere with tumor surgery, such as other accompanying diseases and adhesions due to previous surgery, were excluded. Exclusion criteria were (1) previous abdominal surgery (n = 98); (2) combined surgery because of other diseases (n = 30); (3) total colectomy (n = 7); (4) emergency operation for spontaneous hemorrhage (n = 7); and (5) conversion to open surgery (n = 5). A total of 147 patients were excluded, of which 13 were in the tattooed group (TG) and 134 were in the non-tattooed group (NTG).

Of 127 patients in the tattooed group, a total of 114 patients were enrolled after exclusion of 13 patients. The patients in the NTG were selected by propensity score matching based on age, sex, tumor stage, and operation method (n = 228) (Figure 1). A total of 342 patients were enrolled. Between the two groups, change in [Delta (Δ), preoperative-postoperative] hemoglobin and albumin levels, operation time (min), hospital stay, oral ingestion period, transfusion, and perioperative complications were compared. Tumor stage was determined according to American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 7th edition. Stage 0, I, IIa, IIb, IIc were classified as the N0 group and Stage IIIa, IIIb, IIIc as the N1 or N2 group. Data were obtained from surgical and anesthesia records, pathologic reports, and medical charts.

The study was reviewed and approved by the Chungnam National University Hospital Institutional Review Board, No. CNUH 2017-12-026. This study is a retrospective study using medical records, and personal information protection measures are appropriately established so that the informed consent of the subject can be exempted.

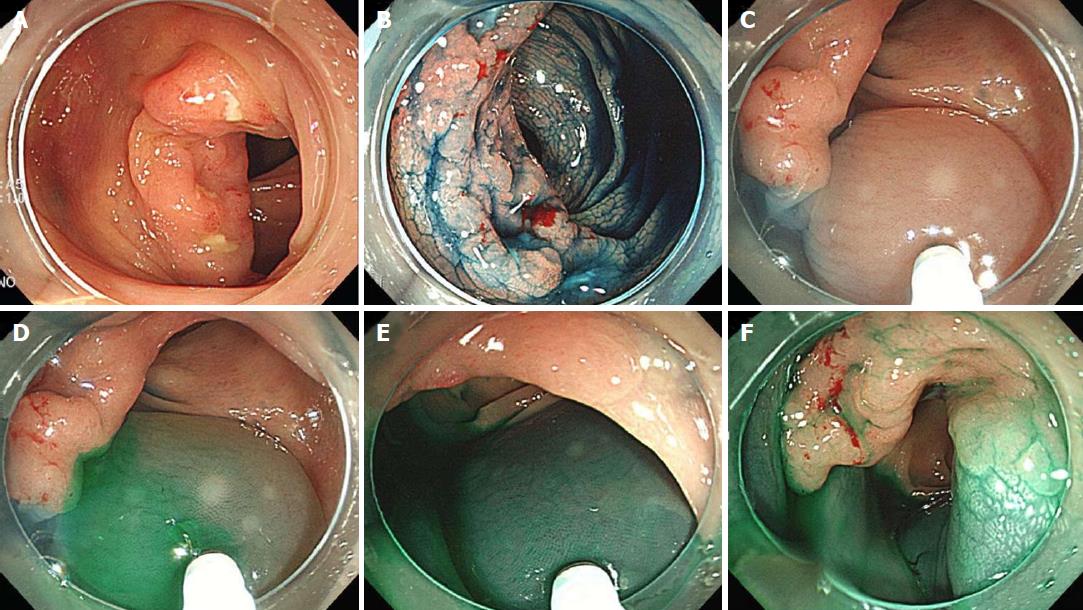

The surgical method was selected by the colorectal surgeon. Tattooing procedures using ICG dye (Daiichi Sankyo Co., Ltd., Japan; Diagnogreen 25 mg) were performed by the gastroenterologist in the endoscopy room the day before the operation. Tattooing was performed circumferentially, close to the lesion, in all 4 quadrants, and with a 23-gauge needle (Figure 2) (Wilson Instruments Co. LTD, WS2416PN2304). The 25 mg of powdered ICG was dissolved in 2 mL of sterilized water. For each injection, 0.5-1 mL of dissolved ICG was used. Endoscopic marking was performed using a two-step method[5,6]. First, 1-2 mL of normal saline solution was injected into the submucosa to make an artificial pseudo polyp. Subsequently, the saline syringe was replaced by the ICG syringe, and 0.5-1 mL of dissolved ICG was injected. All operations were performed by surgeons with more than 10 years of experience (Figure 3). Histopathology results were described by a specialist with a career of more than 20 years.

For selecting the NTG, propensity score-matching was performed using the R software package MatchIt nearest neighbor matching method (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) to avoid selection bias and to obtain enough statistical power. The propensity score model considered age, sex, cancer stage, and surgical method.

The clinical and perioperative results of the study patients were compared between the TG and NTG using χ2 test or Fisher’s extract test and the t-test. Univariate analysis and multivariate analysis was performed with logistic regression on variables identified to be significant on univariate analysis. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were computed by SPSS statistics version 22 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

From January 1, 2012 to December 31, 2016, a total of 1010 patients underwent laparoscopic colectomy, and 127 of these patients were tattooed with ICG (12.57%). No patient who underwent the tattooing procedure had any side effects. The baseline characteristics, histological type, and surgical method of the patients in both groups are compared in Table 1. TG and NTG were not significantly different in age, sex ratio, body mass index (BMI), underlying disease, number of deceased patients, cancer stage by AJCC 7th edition, and operation method. Some differences were not observed because patients were matched by propensity score according to age, sex, stage, and operation method. A total of 289 patients were diagnosed with carcinoma, and most were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. Forty-one patients were diagnosed with adenoma, 16 of whom were low-grade and 25 were high-grade. Male predominance was observed in both TG [Male (M)/Female (F) = 81/31] and NTG (M/F = 153/75), with a mean age of 66.81 ± 10.18 years.

| Baseline characteristics | TG (n = 114) | NTG (n = 228) | P value | ||

| Age | 67.91 ± 8.94 | 66.81 ± 10.18 | 0.326 | ||

| Gender (M/F) | 81/33 (71.1%/28.9%) | 153/75 (67.1%/32.9%) | 0.461 | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.96 ± 2.77 | 24.31 ± 3.16 | 0.311 | ||

| Underlying disease | DM | 22 (19.3) | 48 (21.1) | 0.733 | |

| HTN | 56 (49.1) | 105 (46.1) | 0.542 | ||

| CKD | 2 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | 0.602 | ||

| Hepatitis | 3 (2.7) | 4 (1.8) | 0.574 | ||

| Smoking | Present | 45 (39.5) | 66 (28.9) | 0.044 | |

| Never | 58 (50.9) | 141 (61.8) | |||

| Past | 11(9.6) | 21 (9.3) | |||

| Alcohol | Present | 61 (53.5) | 80 (35.1) | < 0.01 | |

| Never | 31 (27.2) | 89 (39.0) | |||

| Past | 22 (19.3) | 59 (25.9) | |||

| All-cause mortality | 2 (1.8) | 7 (3.1) | 0.723 | ||

| Stage (n = 301) | 0 | 7 (6.1) | 12 (5.3) | 0.931 | |

| I | 57 (50.0) | 118 (51.8) | |||

| II | 15 (13.2) | 30 (13.2) | |||

| III | 23 (20.2) | 39 (17.1) | |||

| Histologic type | Adeno-carcinoma | Well | 6 (5.3) | 4 (1.8) | 0.638 |

| (n = 301) | Moderate | 93 (81.6) | 188 (82.5) | ||

| Poor | 3 (2.6) | 7 (3.1) | |||

| Adenoma | Low grade | 5 (4.4) | 11 (4.8) | ||

| (n = 41) | High grade | 7 (6.1) | 18 (7.9) | ||

| Operation method | Laparoscopic anterior resection | 53 (46.5) | 107 (46.9) | 0.88 | |

| Laparoscopic Rt. hemicolectomy | 25 (21.9) | 70 (30.7) | |||

| Laparoscopic Lt. hemicolectomy | 10 (8.8) | 18 (7.9) | |||

| Complication | Edema | 1 (0.9) | |||

| Intra-abdominal leakage | 1 (0.9) | ||||

| Margin from the lesion | Proximal | 13.45 ± 9.5 cm | |||

| Distal | 7.07 ± 5.2 cm | ||||

Perioperative data were collected on 342 patients (Table 2). Perioperative operation time, hospital stay, and oral ingestion period were shorter in the TG. The Δ hemoglobin (Hb) and Δ Albumin (Alb) showed less intraoperative blood loss in the TG. No significant differences were observed between the groups with respect to blood transfusion and complications. Complications related to endoscopy or tattooing were incurred. According to pathologic results, 1 mucosal edema was reported in the tattooed group. The intraoperative abdominal leakage of ICG was observed in one case, but there was no inflammation or adhesion in the abdominal cavity. Inflammation of the injection site was not reported. There were no cases of margin-positive lesions or intraoperative endoscopy in the tattooed group. The margin from the lesion was proximal 13.45 ± 9.5 cm and distal 7.07 ± 5.2 cm; there was no need for reoperation due to positive margins or resection of the wrong site.

| TG (n = 114) | NTG (n = 228) | P value | |

| Operation time (min) | 174.76 ± 51.6 | 192.63 ± 59.9 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Hb | 0.78 ± 0.76 | 2.2 ± 1.18 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Alb | 0.415 ± 0.44 | 1.08 ± 0.39 | < 0.01 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 9.55 ± 3.36 | 11.42 ± 8.23 | < 0.01 |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.58 ± 0.96 | 2.81 ± 1.90 | < 0.01 |

| Transfusion | 2 (0.02%) | 6 (0.03%) | 0.723 |

| Complication | 7 (0.06%) | 16 (0.07%) | 0.76 |

We compared the perioperative clinical data of the carcinoma group, except for the adenoma group (n = 41), by “N0” and “N1 or N2” group according to stage (Table 3). The N0 group was defined as stage 0, I, IIa, IIb, and IIc (n = 239), and the N1 or N2 group was defined as stage IIIa, IIIb, and IIIc (n = 62). The N0 group showed similar results as the whole group. Operation time (P < 0.05), hospital stay (P < 0.01), and oral ingestion period (P < 0.01) were shorter in the tattooed group. The Δ Hb (P < 0.01) was lower in the TG than in the NTG, indicating lower blood loss in the TG compared with the NTG; further, Δ Alb (P < 0.01) was also lower in the TG compared with the NTG. The advanced stage group showed similar results in Δ Hb (P < 0.01) and Δ Alb (P < 0.01), but not in operation time (P = 0.278), hospital stay (P = 0.449) and oral ingestion period (P = 0.064).

| Staging | TG (n = 102) | NTG (n = 199) | P value | |

| N0 group (Stage 0 + I +IIa + IIb +IIc) | Operation time (min) | 172.70 ± 48.87 | 190.34 ± 60.18 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Hb | 0.86 ± 0.79 | 2.16 ± 1.16 | < 0.01 | |

| (n = 239) | Δ Alb | 0.40 ± 0.47 | 1.07 ± 0.39 | < 0.01 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 9.37 ± 2.91 | 11.53 ± 8.56 | < 0.01 | |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.49 ± 0.87 | 2.68 ± 1.16 | < 0.01 | |

| N1 or N2 group | Operation time (min) | 177.91 ± 56.74 | 195.69 ± 64.59 | 0.278 |

| (Stage IIIa +IIIb +IIIc) | Δ Hb | 0.50 ± 0.71 | 2.05 ± 1.27 | < 0.01 |

| (n = 62) | Δ Alb | 0.39 ± 0.41 | 1.06 ± 0.41 | < 0.01 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 10.74 ± 5.00 | 12.23 ± 8.53 | 0.449 | |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.83 ± 1.23 | 3.31 ± 3.62 | 0.064 |

All 342 patients underwent colonic resection. To investigate the efficacy of tattooing for different colonic surgical procedures, namely laparoscopic anterior resection (LAR) (n = 160), left (Lt) hemicolectomy (n = 28), and right (Rt) hemicolectomy (n = 95), the patients were divided into TG and NTG and the parameters Δ Hb, Δ Alb, and operation time were compared between them (Table 4). The LAR group showed a similar trend, as noted previously. For all three groups, Δ Hb (P < 0.01) and Δ Alb (P < 0.01) were lower in the TG than in the NTG.

| Method | TG (n = 88) | NTG (n = 195) | P value | |

| LAR | Operation time (min) | 157.58 ± 43.42 | 180.33 ± 58.65 | < 0.01 |

| (n = 160) | Δ Hb | 0.86 ± 0.79 | 2.18 ± 1.23 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Alb | 0.41 ± 0.52 | 1.05 ± 0.41 | < 0.01 | |

| Hospital stay (d) | 8.79 ± 2.33 | 10.26 ± 5.79 | < 0.01 | |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.43 ± 0.79 | 2.85 ± 1.83 | < 0.01 | |

| Lt hemicolectomy | Operation time (min) | 206.3 ± 33.07 | 219.61 ± 60.67 | 0.45 |

| (n = 28) | Δ Hb | 0.35 ± 0.50 | 2.19 ± 1.14 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Alb | 0.40 ± 0.29 | 1.09 ± 0.40 | < 0.01 | |

| Hospital stay (d) | 12.00 ± 5.85 | 11.28 ± 4.49 | 0.72 | |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.7 ± 0.82 | 2.5 ± 0.70 | < 0.01 | |

| Rt hemicolectomy | Operation time (min) | 186.00 ± 49.35 | 197.14 ± 54.89 | 0.37 |

| (n = 95) | Δ Hb | 0.73 ± 0.68 | 2.06 ± 1.08 | < 0.01 |

| Δ Alb | 0.51 ± 0.43 | 1.04 ± 0.38 | < 0.01 | |

| Hospital stay (d) | 10.36 ± 3.92 | 10.71 ± 5.25 | 0.76 | |

| Oral intake (d) | 1.56 ± 0.96 | 2.74 ± 1.36 | < 0.01 |

Univariate analysis using a logistic regression model showed statistical significance of colonoscopic tattooing with ICG for variables of operation time (min) (P < 0.01), Δ Hb, Δ Alb (P < 0.01), hospital stay (d) (P = 0.023), and oral intake (d) (P = 0.259). Multivariate analysis shows the results of the logistic regression models for operation time, Δ Hb, Δ Alb, hospital stay, and oral intake (Table 5).

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (95%CI) | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value | |

| Operation time (min) | 0.994 (0.990-0.998) | 0.008 | 0.999 (0.993-1.006) | 0.835 |

| Δ Hb | 0.149 (0.096-0.231) | < 0.001 | 0.207 (0.119-0.361) | < 0.01 |

| Δ Alb | 0.021 (0.009-0.049) | < 0.001 | 0.056 (0.021-0.145) | < 0.01 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 0.937 (0.886-0.991) | 0.023 | 0.987 (0.909-1.071) | 0.753 |

| Oral intake (d) | 0.259 (0.181-0.371) | < 0.001 | 0.417 (0.280-0.621) | < 0.01 |

The aim of preoperative tumor lesion marking is to exactly locate the lesions in laparoscopic surgeries and to perform excision as needed. In this study, whether tattooing with ICG can help identify the correct lesion during laparoscopic surgery and have a positive effect was evaluated. Because laparoscopic surgery has become a major trend for the treatment of colorectal cancer, preoperative tumor markings are needed to determine the exact location of the lesion in a limited field of view[7].

Methods of marking include tattooing, using metal clips, radio opaque, integrated circuit materials[8], and intraoperative endoscopy. As introduced in other studies, tattooing methods include staining using sterile carbon compounds[9], India ink, and autologous blood infusions. The tattooing method is relatively inexpensive and quick[10]. However, the disadvantage of tattooing is that the marking disappears over time. The complication rate is as low as 0.22%[11], but if a complication occurs, it is mainly caused by leakage due to transmural injection[12].

Marking with metallic materials has the disadvantage that sometimes they are lost and not palpable during laparoscopic surgery. Even Scope Guide endoscope[13], intraoperative endoscopy, radiation or integrated circuits, near-infrared localization and sentinel LN mapping with ICG[14] to detect the surgical site will require special instruments and are relatively expensive[15].

Tattooing using India ink is the commonly used method. India ink is a mixture of several substances[4], which can induce an inflammatory reaction through its constituent substances, and is recommended for use under an autoclave and after dilution to prevent complications[4]. Various complications have been reported depending on the amount and location of leakage[11,16-20]. There have been small studies that used ICG to solve the problems of India ink[2,21].

ICG is a safe dyeing method with a low risk of complications, except that it cannot be used in people with iodine allergies. Even if trans-abdominal spillage occurs, local inflammation or coloration is less likely, and formation of adhesion or granuloma is extremely rare compared to India ink. Some animal studies have reported local inflammation or ulceration, but that did not occur in this study. In a study comparing ICG and ICG dye in rabbits, the ICG group included 22 cases, with repeated laparotomy performed at 1, 3, and 7 d, and the India ink group included 16 cases, with repeated laparotomy performed at 1 and 5 mo. Mucosal ulcers and inflammation were reported in the ICG group and severe inflammation was observed in the undiluted and 1:10 concentration India ink groups[3]. However, there are limitations with regard to the time and frequency of laparotomy between the two agents in that study, as short-term repeated laparotomy results were only examined in the ICG group.

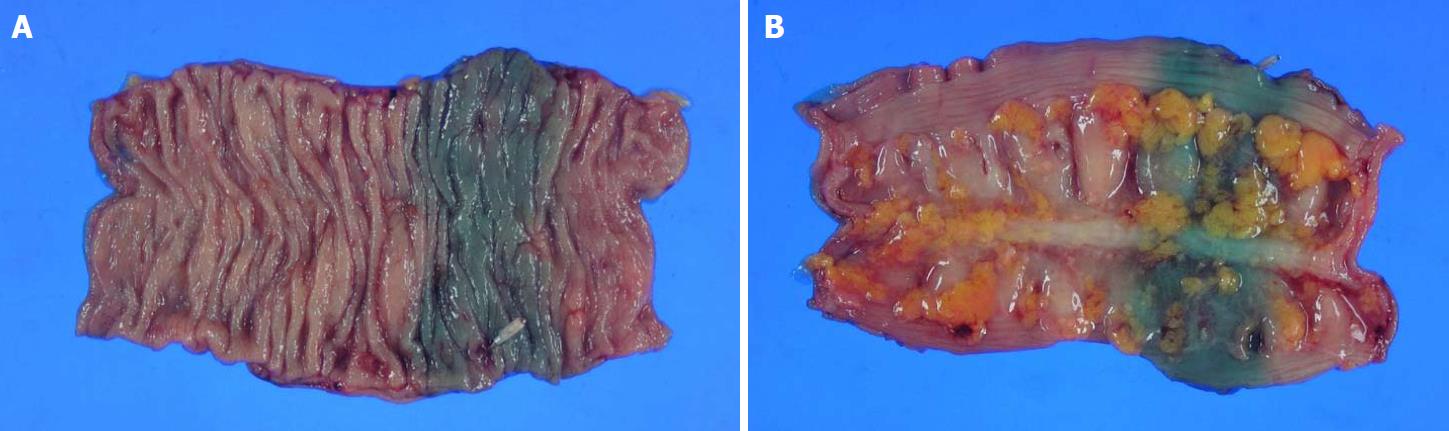

According to Miyoshi et al[2], in a study of 40 patients, 29 patients who had undergone surgery within 8 d of tattooing with ICG showed green markings in the surgical field. It is well known that the tattooing method using ICG is simple because it does not require additional tools other than performing endoscopy in general, and it is well known that laparoscopic surgical vision is secured when applied with the circumferential tattooing method. All patients underwent the circumferential tattooing method using ICG on the day prior to surgery and underwent surgery within 24 h. In the postoperative histopathologic gross photographs (Figure 4), the lesions were well-observed and well-stained, which makes it possible to quickly identify the lesions, and the correct resection range can be easily determined, thereby shortening the operation time and preventing complications caused by resection of the inappropriate part. In addition, reduction of blood loss before and after surgery decreases the likelihood of blood transfusions and results in fewer hospitalization days, fewer complications, and a shorter oral ingestion period.

To compensate for the difference in the operation time due to lymph node dissection in the advanced stage, Stage 0, I, IIa, IIb, and IIc were classified as the N0 group and Stage IIIa, IIIb, and IIIc as the “N1 or N2” group. TG and NTG were compared between the “N0” and “N1 or N2” group. Statistical analysis showed that TG had a favorable effect, such as shortened operation time, decreased blood and albumin loss, fewer hospital days, and decreased complications, in the N0 tumor group because lesions with a small tumor size or those that are less invasive are not well recognized during laparoscopic surgery.

Subgroup analysis of T1N0 (n = 196) vs T1N1, 2 (n = 22) was performed to compare the efficacy of tattooing with or without lymph node invasion in T1 lesions of relatively small size and invasion. In the non-lymph node invasive group, Δ Hb (P < 0.01) and Δ Alb (P < 0.01) operative time (P < 0.01), oral intake (P < 0.01), and hospital stay (P = 0.01) were shorter in TG. In the lymph node invasive group, the blood loss expressed by Δ Hb (0.78 ± 0.7 g/dL vs 2.28 ± 1.1 g/dL, P < 0.01) and Δ Alb (0.34 ± 0.4 g/dL vs 1.10 ± 0.3 g/dL, P < 0.01) was low. Operative time (154.70 ± 40.1 min vs 178.73 ± 65.4 min, P = 0.320) and oral intake (1.70 ± 0.9 d vs 2.55 ± 1.0 d, P = 0.067) were shorter in TG, but the difference was not statistically significant. With or without lymph node metastasis, this suggests that tattooing has a significant effect of reducing the amount of blood loss by preventing the resection of unnecessary parts.

To investigate the differences in results according to the surgical method, LAR, left hemicolectomy and right hemicolectomy, statistical analysis was performed and showed a difference in operative time between the two groups in LAR. However, in left and right hemicolectomy, there was no significant difference between TG and NTG in the reduction of operation time. However, it was found that blood loss and the number of hospitalization days were reduced.

A multivariate analysis was conducted. There was strong evidence that after controlling for other variables, the tattooing procedure using ICG was associated with less blood loss (less Δ Hb, Δ Alb) and post-operative bowel recovery (shorter oral intake day).

Therefore, if tattooing is done within a reasonable time, preoperative tattooing with ICG is useful for laparoscopic colectomy, especially for the N0 group of colon cancer and LAR.

The limitations of this study include its retrospective and single-institution nature. Propensity score matching was performed in the control group to overcome this limitation. As the TG showed male predominance, the total group showed male predominance. The need for tattooing was determined entirely by surgeons. In addition, the differences according to surgical method were analyzed, but there were relatively fewer cases of left hemicolectomy than the other surgical methods. More cases and years of data are needed to overcome this limitation.

Endoscopic marking of colonic lesions has become more important in recent years when laparoscopic surgery has become the mainstream. A less complicated, simple, and effective tattooing method was required. The authors aimed to prove that tattooing using indocyanine green (ICG) is beneficial in laparoscopic surgery of colon tumor.

Although tattooing using India ink has been used for colon tumor location, adhesion due to local inflammation is a problem, and granulation or abscess formation may occur when transabdominal spillage. ICG is a safe substance used in the i.v. injection for liver function assessment, but it is less used due to its shorter duration. ICG can be used effectively at appropriate intervals until surgery.

The authors wanted to prove that tattooing with ICG can be clinically effective if appropriate time and methods are used.

The tattooed group (TG) contained 114 patients, and the non-tattooed group (NTG) comprised 228 patients selected by propensity score matching of subjects based on age, sex, tumor staging, and operation method. Between the groups, the perioperative parameters were compared. To compensate for the difference in the operation time due to lymph node dissection in the advanced stage, lymph node positive (N1 or N2) and negative (N0) groups were compared, especially T1N0, T1N1 or T1N2. To investigate the differences in results according to the surgical method, each surgical method was compared.

Without major complications, all tattooed lesions are safely resected. Perioperative operation times, hospital stays, and oral ingestion periods were shorter in the TG. The Δ hemoglobin and Δ albumin showed less intraoperative blood loss in the tattooed group. With or without lymph node metastasis, tattooing has a significant effect of reducing the amount of blood loss by preventing the resection of unnecessary parts. Especially in patients without lymph node dissection, other perioperative parameters showed better results. When classified according to type of surgery, there were statistically significant differences in operative time and other parameters in the LAR group.

Tattooing using ICG is a simple and effective method with few complications and can be used in laparoscopic colon surgery, especially in the N0 colon cancer and LAR groups.

Based on results from perioperative data, if the time to surgery and the injection method are appropriate, colonoscopic tattooing with ICG was shown to be effective with limited complications.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Milone M, Negoi I S- Editor: Ma RY L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu YXJ

| 1. | Wexner SD, Cohen SM, Ulrich A, Reissman P. Laparoscopic colorectal surgery-are we being honest with our patients? Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:723-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Miyoshi N, Ohue M, Noura S, Yano M, Sasaki Y, Kishi K, Yamada T, Miyashiro I, Ohigashi H, Iishi H. Surgical usefulness of indocyanine green as an alternative to India ink for endoscopic marking. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:347-351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Price N, Gottfried MR, Clary E, Lawson DC, Baillie J, Mergener K, Westcott C, Eubanks S, Pappas TN. Safety and efficacy of India ink and indocyanine green as colonic tattooing agents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:438-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | ASGE Technology Committee. Kethu SR, Banerjee S, Desilets D, Diehl DL, Farraye FA, Kaul V, Kwon RS, Mamula P, Pedrosa MC, Rodriguez SA, Wong Kee Song LM, Tierney WM. Endoscopic tattooing. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:681-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fu KI, Fujii T, Kato S, Sano Y, Koba I, Mera K, Saito H, Yoshino T, Sugito M, Yoshida S. A new endoscopic tattooing technique for identifying the location of colonic lesions during laparoscopic surgery: a comparison with the conventional technique. Endoscopy. 2001;33:687-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sawaki A, Nakamura T, Suzuki T, Hara K, Kato T, Kato T, Hirai T, Kanemitsu Y, Okubo K, Tanaka K. A two-step method for marking polypectomy sites in the colon and rectum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:735-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim SH, Milsom JW, Church JM, Ludwig KA, Garcia-Ruiz A, Okuda J, Fazio VW. Perioperative tumor localization for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 1997;11:1013-1016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wada Y, Miyoshi N, Ohue M, Yasui M, Fujino S, Tomokuni A, Sugimura K, Akita H, Moon JH, Takahashi H. Endoscopic marking clip with an IC tag and receiving antenna to detect localization during laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:3056-3060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Askin MP, Waye JD, Fiedler L, Harpaz N. Tattoo of colonic neoplasms in 113 patients with a new sterile carbon compound. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:339-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feingold DL, Addona T, Forde KA, Arnell TD, Carter JJ, Huang EH, Whelan RL. Safety and reliability of tattooing colorectal neoplasms prior to laparoscopic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:543-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nizam R, Siddiqi N, Landas SK, Kaplan DS, Holtzapple PG. Colonic tattooing with India ink: benefits, risks, and alternatives. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1804-1808. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Acuna SA, Elmi M, Shah PS, Coburn NG, Quereshy FA. Preoperative localization of colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:2366-2379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ellul P, Fogden E, Simpson C, Buhagiar A, McKaig B, Swarbrick E, Veitch A. Colonic tumour localization using an endoscope positioning device. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:488-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Buda A, Dell'Anna T, Vecchione F, Verri D, Di Martino G, Milani R. Near-Infrared Sentinel Lymph Node Mapping With Indocyanine Green Using the VITOM II ICG Exoscope for Open Surgery for Gynecologic Malignancies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2016;23:628-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cho YB, Lee WY, Yun HR, Lee WS, Yun SH, Chun HK. Tumor localization for laparoscopic colorectal surgery. World J Surg. 2007;31:1491-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coman E, Brandt LJ, Brenner S, Frank M, Sablay B, Bennett B. Fat necrosis and inflammatory pseudotumor due to endoscopic tattooing of the colon with india ink. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Trakarnsanga A, Akaraviputh T. Endoscopic tattooing of colorectal lesions: Is it a risk-free procedure? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kim JH, Kim WH. [Colonoscopic Tattooing of Colonic Lesions]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2015;66:190-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park JW, Sohn DK, Hong CW, Han KS, Choi DH, Chang HJ, Lim SB, Choi HS, Jeong SY. The usefulness of preoperative colonoscopic tattooing using a saline test injection method with prepackaged sterile India ink for localization in laparoscopic colorectal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:501-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hwang MR, Sohn DK, Park JW, Kim BC, Hong CW, Han KS, Chang HJ, Oh JH. Small-dose India ink tattooing for preoperative localization of colorectal tumor. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:731-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |