Published online Nov 6, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.624

Peer-review started: July 16, 2018

First decision: September 10, 2018

Revised: September 16, 2018

Accepted: October 11, 2018

Article in press: October 11, 2018

Published online: November 6, 2018

Processing time: 113 Days and 16.2 Hours

To examine the practice pattern in Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC), i.e., gastroenterology (GI)/surgery referrals and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), for pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCNs) after the region-wide dissemination of the PCN management algorithm.

Retrospective review was performed; patients with PCN diagnosis given between April 2012 and April 2015 (18 mo before and after the publication of the algorithm) in KPSC (integrated health system with 15 hospitals and 202 medical offices in Southern California) were identified.

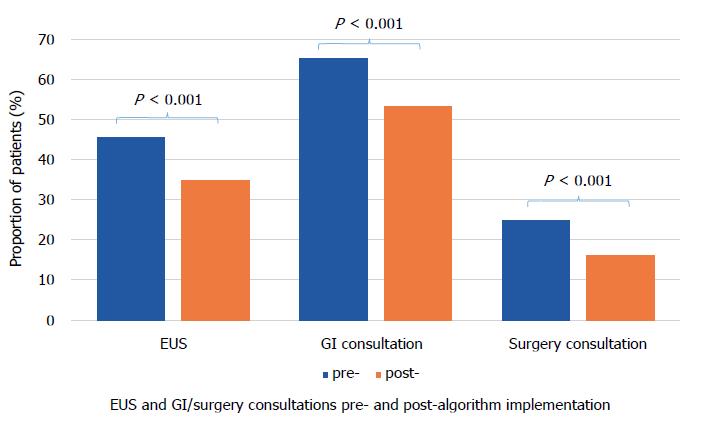

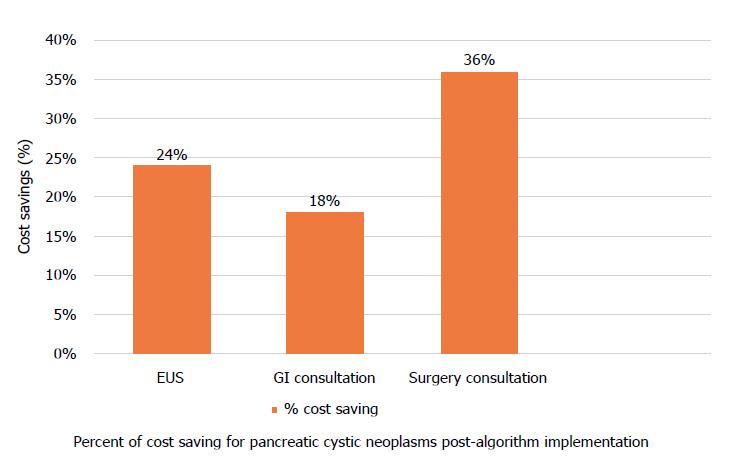

2558 (1157 pre- and 1401 post-algorithm) received a new diagnosis of PCN in the study period. There was no difference in the mean cyst size (pre- 19.1 mm vs post- 18.5 mm, P = 0.119). A smaller percentage of PCNs resulted in EUS after the implementation of the algorithm (pre- 45.5% vs post- 34.8%, P < 0.001). A smaller proportion of patients were referred for GI (pre- 65.2% vs post- 53.3%, P < 0.001) and surgery consultations (pre- 24.8% vs post- 16%, P < 0.001) for PCN after the implementation. There was no significant change in operations for PCNs. Cost of diagnostic care was reduced after the implementation by 24%, 18%, and 36% for EUS, GI, and surgery consultations, respectively, with total cost saving of 24%.

In the current healthcare climate, there is increased need to optimize resource utilization. Dissemination of an algorithm for PCN management in an integrated health system resulted in fewer EUS and GI/surgery referrals, likely by aiding the physicians ordering imaging studies in the decision making for the management of PCNs. This translated to cost saving of 24%, 18%, and 36% for EUS, GI, and surgical consultations, respectively, with total diagnostic cost saving of 24%.

Core tip: There are ever-increasing numbers of detected incidental, asymptomatic pancreatic cystic neoplasms. This increasing detection has led to work up and treatment guidelines that have been a challenging clinical entity for primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, radiologists and surgeons alike. Our retrospective study included over 2500 patients spanning multiple large hospital centers within an integrative health system. This research demonstrated that the dissemination of an algorithm for pancreatic cyst management in an integrated health system increased the threshold for referrals for intervention and workup, resulting in significant cost savings on the order of up to millions of dollars, without compromising patient care.

- Citation: Nguyen AK, Girgis A, Tekeste T, Chang K, Adeyemo M, Eskandari A, Alonso E, Yaramada P, Chaya C, Ko A, Burke E, Roggow I, Butler R, Kawatkar A, Lim BS. Effect of a region-wide incorporation of an algorithm based on the 2012 international consensus guideline on the practice pattern for the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms in an integrated health system. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(13): 624-631

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i13/624.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i13.624

There has been in an increase in the frequency of incidental pancreatic cyst diagnosis. Pancreatic cysts detected on computed tomography (CT) scans are reported between 1.2% and 2.6%. Magnetic resonance imaging has even a higher detection ranging between 13.5% and 19.9%[1]. This increased detection rate can be attributed to a more liberal usage of cross-sectional imaging studies and the improved quality of the imaging devices[2]. The management of these pancreatic cysts remains a challenge. While the overall risk of malignancy in incidentally detected pancreatic cysts is low, pancreatic cancer has an extremely poor prognosis once acquired. The mortality rates for both pancreatic adenocarcinoma and intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN)-related pancreatic adenocarcinoma have not changed in the recent years[3,4].

The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy released the first set of pancreatic cyst management guidelines in 2005 addressing the role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and the management of pancreatic cystic lesions[5]. This was followed by the international consensus guidelines, or Sendai guidelines, established by the International Association of Pancreatology, which emphasized the management for IPMN and mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN) based on symptoms, size of the cyst and the presence of high risk stigmata[6]. In 2007, the American College of Gastroenterology proposed a set of guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with neoplastic pancreatic cysts based on published data to date[7]. International Association of Pancreatology updated their guidelines in 2012, known as the Fukuoka guidelines[8], in which high-risk stigmata and worrisome features have been redefined to stratify the risk of malignancy in branch duct IPMN, and the resection criteria was modified to be more conservative.

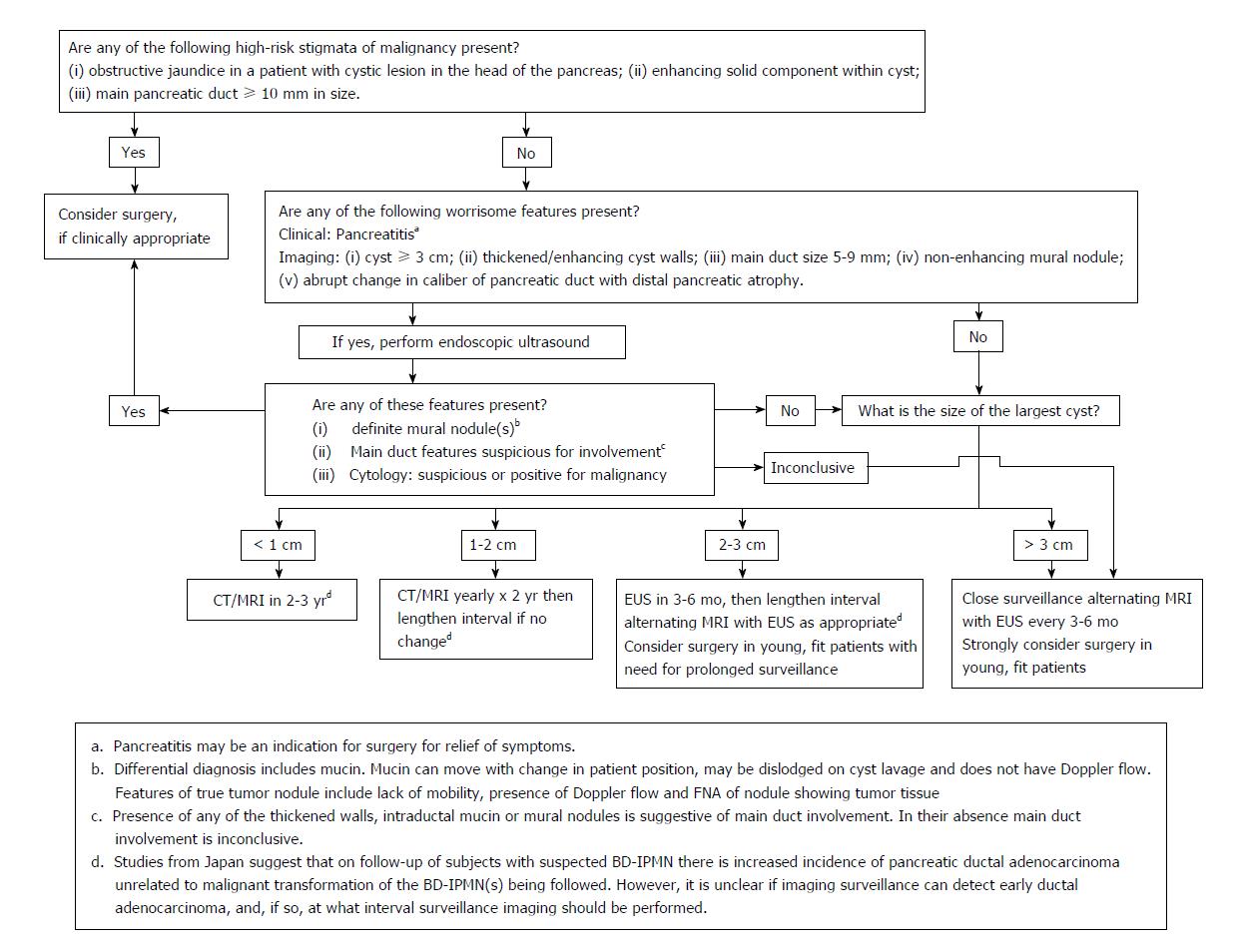

Based on the updated international consensus guidelines (Figure 1), Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) published a regional algorithm in October 2013 with radiology reports including a concise summary of recommendations (Table 1). The aim of this study was to examine the practice pattern in KPSC, i.e., gastroenterology (GI)/surgery referrals and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), for pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) after the region-wide dissemination of this algorithm.

| Size of Lesion | Recommendations |

| 1-5 mm | Too small to characterize, considered benign |

| No further imaging follow-up recommended | |

| 6-9 mm | Consider single follow-up in 2-3 yr, preferably MRCP/MRI pancreas |

| If stable at follow up, no further imaging follow-up recommended | |

| 1-1.9 cm | Consider follow-up MRCP/MRI or CT pancreas in 1-2 yr |

| If stable at follow-up, lengthen interval imaging follow-up to 2-3 yr | |

| 2-2.9 cm | Consider baseline EUS, then follow-up MRCP/MRI or CT pancreas in 6-12 mo |

| Consider surgery in young, fit patients with need for prolonged surveillance | |

| If stable at follow-up, lengthen interval imaging follow-up to 1-2 yr | |

| ≥ 3 cm | Consider baseline or follow-up EUS, then follow-up MRCP/MRI or CT pancreas in 3-6 mo |

| Strongly consider surgery in young, fit patients |

The Institutional Review Board of KPSC approved the study. A retrospective review was performed to identify patients who were given the PCN diagnosis given between April 2012 and April 2015 (18 mo before and after the publication of the algorithm) in KPSC (integrated health system with 15 hospitals and 202 medical offices in Southern California). Patients over the age of 18 years with a diagnosis of pancreatic cysts based on International Classification of Disease - Clinical Modification 9 code (ICD-9577.2) were included. Patients were excluded for the following reasons: (1) cancer diagnosis made or suspected at the time of PCN diagnosis based on cross sectional imaging prior to referral(s); (2) history of recent pancreatitis; (3) diagnosis consistent with pseudocyst; (4) history of pancreatic cancer; (5) history of pancreatic surgery; (6) diagnosis of PCN in error; and (7) EUS performed for reasons other than PCN with incidental finding of PCN during EUS. Diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy was confirmed through cross-reference with a prospectively maintained internal KPSC cancer registry.

For cost analysis portion of the study, the cost of EUS was based on 2017 Medicare national average payment for hospital out-patient procedure (CPT® 43238). For GI and surgery consultations, CPT® codes 99201-99205 were used. In order to obtain the weighted average of the 5 codes, a sample of 60 patients’ data (30 for GI and 30 for surgery) were randomly selected and the distribution of the codes was utilized for the calculation of the weights. Extrapolation of the result to the United States population was based on the estimation of the incidence of pancreatic cyst in the United States being between 3% and 15%, percentage increasing with age, according to the American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Lower end of this range (3%) was used for our analysis.

Pre- and post-implementation demographic characteristics and practice pattern measures/outcomes were compared using χ2-test for categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. For the calculation of pancreas cancer incidence rates, patients were included if they had KPSC membership at time of PCN diagnosis. Follow-up time was calculated as time from PCN diagnosis to the first of pancreas cancer diagnosis, end of KPSC membership, or May 1, 2017. Incidence rates were compared using the mid-P test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States).

2558 (1157 pre- and 1401 post-algorithm) received a new diagnosis of PCN in the study period. There was no difference in the mean cyst size (pre- 19.1 mm vs post- 18.5 mm, P = 0.119). Mean age at diagnosis was 67.1 for pre- and 68.4 for post-algorithm (P = 0.013). There was no difference in gender distribution (65.8% female for pre- and 62.6% female for post-, P = 0.096). Likewise, there was no difference in ethnicities (Table 2).

| Pre-algorithm | Post-algorithm | Total | P value | |

| Number of patients | 1157 (45.23) | 1401 (54.77) | 2558 | |

| Imaging at diagnosis | 0.032 | |||

| CT | 822 (71) | 958 (68.4) | 1780 (69.6) | |

| MR | 215 (18.6) | 317 (22.6) | 532 (20.8) | |

| Ultrasound | 120 (10.4) | 126 (9) | 246 (9.6) | |

| Largest dimension (mm) | 0.119 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 19.1 (16.86) | 18.5 (17.90) | 18.8 (17.44) | |

| Range | (2.0-210.0) | (0.9-204.0) | (0.9-210.0) | |

| Age (yr) | 0.013 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 67.1 (13.77) | 68.4 (13.92) | 67.8 (13.86) | |

| Range | (20.0-95.0) | (20.0-100.0) | (20.0-100.0) | |

| Sex | 0.096 | |||

| Male | 396 (34.2) | 524 (37.4) | 920 (36) | |

| Female | 761 (65.8) | 877 (62.6) | 1638 (64) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.179 | |||

| Asian | 159 (13.7) | 174 (12.4) | 333 (13.0) | |

| African American | 129 (11.1) | 126 (9.0) | 255 (10.0) | |

| Latino | 270 (23.3) | 370 (26.4) | 640 (25) | |

| Others/unknown | 15 (1.3) | 20 (1.4) | 35 (1.4) | |

| White | 584 (50.5) | 711 (50.7) | 1295 (50.6) |

A smaller percentage of PCNs resulted in EUS after the implementation of the algorithm (pre- 45.5% vs post- 34.8%, P < 0.001). A smaller proportion of patients were referred for GI (pre- 65.2% vs post- 53.3%, P < 0.001) and surgery consultations (pre- 24.8% vs post- 16%, P < 0.001) for PCN after the implementation (Figure 2). Proportion of operations performed for PCNs were 4.1% pre- and 3.9% post-algorithm (P = 0.705).

The incidence rate of pancreatic cancer after diagnosis of PCN (between the time of PCN diagnosis and May 1, 2017 or end of KPSC membership), excluding those that were diagnosed at the time of initial work-up, was 2.41 per 1000-person years (95%CI: 1.16-4.44) for pre-algorithm and 2.42 per 1000-person years (95%CI: 1.04-4.77) for post-algorithm (P = 0.4943).

After the implementation, cost of diagnostic care was reduced by 24%, 18%, and 36% for EUS, GI, and surgery consultations, respectively (Figure 3). Total cost saving was 24%. If we assume that the incidence of pancreatic cysts in KPSC is 1000 (estimate based on our search using ICD-9), total annual cost saving would be $194696 ($584088 during the entire study period), $173874 for EUS, $9805 for GI consultation, and $11018 for surgery consultation. However, this incidence may be significantly underestimated; KPSC incidence using the lower end of the US incidence (3%, range 3%-15%) would be 98040 given that KPSC adult population is 3268000. Using this figure as the incidence, total cost saving would increase to $19 Million ($17 Million for EUS, $1 Million for GI consultations, and $1 Million for surgery consultations). These findings were then extrapolated to the national level. The US population estimate as of July 1st, 2017 was 325719178 with 251455205 adults. Using the 3% incidence rate, the cost saving as a result of such algorithm implementation would be $1.49 Billion ($1.34 Billion for EUS, $72 Million for GI consultations, and $81 Million for surgery consultations).

The work up and treatment guidelines of pancreatic cystic neoplasms have been a challenging clinical entity for primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, radiologists and surgeons alike. There is increasing detection of incidental, asymptomatic lesions with one out of every ten patients over 70 years of age diagnosed with PCNs[9-10]. These findings are of great importance as patients with pancreatic cysts have been shown to have significantly higher risk of pancreatic cancer[11].

In 2006, international consensus guideline was developed to assist in the management of pancreatic cystic neoplasms. It focused on the treatment of MCN, main duct and branch duct IPMN recommending the resection of main duct/mixed type IPMNs and MCNs. The 2006 international consensus guideline went on to note an algorithm for the management of the non-resected branch duct IPMNs based on size on high resolution CT, MRCP, or EUS with annual follow up for IPMNs less than 10 mm, 6-12 mo follow up for those 10 to 20 mm, and 3-6 mo follow up for those greater than 20 mm; lengthening of the interval was allowable if there is no change in size after two years. Indication for resection included symptoms, mural nodules, cyst size greater than 30 mm, and dilation of main pancreatic duct more than 6 mm[6]. These indications were shown in multiple studies to have high sensitivity for detection of malignancy of 97.3%[12-14]. In addition, this landmark algorithm illustrated the ability to differentiate high and low risk lesions effectively[3].

A revision was published in 2012 by Tanaka et al[8], known as the Fukuoka guidelines, based on new research and literature that developed since the original 2006 international consensus guidelines. The new guidelines differed from the 2006 version primarily with the addition of the new concepts of “high-risk stigmata” and “worrisome features”, which were defined to stratify the risk of malignancy in branch duct (BD)-IPMN aiding in decision for resection and the frequency of surveillance. EUS was recommended for further evaluation for “worrisome features”, which included cysts ≥ 3 cm, thickened enhanced cyst walls, non-enhanced mural nodules, MPD of 5-9 mm, acute change in MPD size, and lymphadenopathy. Surgery was recommended for “high-risk stigmata” such as enhanced solid components and MPD size ≥ 10 mm. Resection was still recommended in all surgically fit patients with MD-IPMN or MCN as was the case in the previous version. However, the indications for resection of BD-IPMN became more conservative, i.e., BD-IPMNs of > 3 cm without “high-risk stigmata” could now be observed without immediate resection.

Based on the 2012 Fukuoka guidelines (Figure 1), KPSC published a regional algorithm in October 2013 with radiology reports including a brief summary of recommendations. Our retrospective study, which analyzed patients with PCN diagnosis given between April 2012 and April 2015 and their subsequent management plan based on the KPSC algorithm, showed that referrals for EUS, GI consultation, and surgery consultation were significantly lower after the publication and dissemination of the algorithm resulting in cost savings of 24%, 18%, and 36% for EUS, GI consultation, and surgical consultation respectively. At a conservative 3% incidence, the results of our study extrapolate to an annual cost saving of $19 Million for KPSC, and at the US level, the cost saving as a result of nationwide dissemination and effective usage of such algorithm would be $1.49 Billion.

There are a few important details to be discussed as to how KPSC incorporated the PCN algorithm in clinical practice. Realizing that the detailed flow diagram based on the Fukuoka algorithm (Figure 1) may be too complex to be utilized in a busy clinical setting (often times non-GI) in making real-time decisions, a simplified version depicted in Table 1 was made readily available for the frontline physicians to view. To increase the practicality of such an algorithm, KPSC added these simplified recommendations at the end of the reports of radiologic studies that detected PCNs. An advantage of creating and disseminating this type of algorithm in a healthcare system is the practice of cost-effective and resource-sensitive medicine. Cost savings leads to the ability to shunt the resulting fiscal surplus to other important aspects of healthcare. Physician and ancillary staff time spent in addressing and managing PCNs are valuable and limited assets in healthcare as well. Therefore, preventing unnecessary referrals for GI/surgery consultations and EUS via the recommendations to frontline physicians would allow for the practice of resource-sensitive medicine.

Since the study was conducted, the revised Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN was published in 2017, where the working group made minor revisions regarding prediction of invasive carcinoma and high-grade dysplasia, surveillance, and postoperative follow-up of IPMN[15].

Limitation of the study is its retrospective nature. Another limitation might be that the study cohort was consisted a specific population within a managed healthcare setting in Southern California, which could make extrapolation of the results to other populations, e.g., uninsured patients and those in other parts of the world, less ideal. Lastly, the follow-up period of this study was not long. However, the primary outcome of the study was not to examine the long-term natural course of PCNs but to evaluate the practice pattern change (i.e., EUS volume and GI/surgery consultations) months preceding and following the implementation of this world-wide algorithm. The aim of the study was not to show how the algorithm can improve patient outcome but to show the cost savings that could result from the change in clinical practice following the dissemination of such an algorithm. Regardless, we did follow the patients until May 1, 2017 (60 mo from the beginning of the study period) to compare the rates of pancreatic malignancy between the two groups, which were not statistically significant. Therefore, although the study was not designed to show how the algorithm can improve patient outcome, we conclude that the implementation of the algorithm did not result in worse patient outcome in our study period. A much longer study would be needed to examine the long-term outcome of not only the PCN algorithm(s) but also the natural course of PCNs themselves.

In conclusion, there is increased pressure to optimize resource utilization in the current healthcare climate. Our retrospective study demonstrated that the dissemination of an algorithm for pancreatic cyst management in an integrated health system increased the threshold for referrals for intervention and workup, possibly due to increasing the confidence level of physicians ordering imaging studies in managing PCNs, resulting in significant cost savings without compromising patient care.

There has been in an increase in the frequency of incidental pancreatic cyst diagnosis. The management of these pancreatic cysts is a significant challenge that clinicians have to face because while the overall risk of malignancy in incidentally detected pancreatic cysts is low, pancreatic cancer has an extremely poor prognosis once acquired. Various gastroenterology societies have published pancreatic cyst management guidelines, one of which was the Sendai guidelines established by the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP). IAP updated their guidelines in 2012, known as the Fukuoka guidelines, in which the resection criteria was modified to be more conservative. Based on the Fukuoka guidelines, Kaiser Permanente Southern California (KPSC) published a regional algorithm in October 2013 with radiology reports including a concise summary of recommendations.

Healthcare budget is limited in all countries around the world. Therefore, there is increased pressure to optimize resource utilization. We wanted to demonstrate through our study that the wide dissemination of an algorithm for pancreatic cyst management in an integrated health system such as KPSC can decrease the endoscopic ultrasound/gastroenterology/surgery referrals from the frontline physicians who detect incidental pancreatic cysts on cross sectional imaging, which then would result in significant cost savings.

The objective of this study was to examine the practice pattern in KPSC, i.e., gastroenterology (GI)/surgery referrals and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), for pancreatic cystic neoplasms (PCN) after the region-wide dissemination of the pancreatic cyst management algorithm derived from the Fukuoka guidelines published in 2012.

This was a retrospective analysis of patients who were given the PCN diagnosis between April 2012 and April 2015 (18 mo before and after the publication of the algorithm) in KPSC (integrated health system with 15 hospitals and 202 medical offices in Southern California). Patients over the age of 18 years with a diagnosis of pancreatic cysts based on International Classification of Disease - Clinical Modification 9 code (ICD-9 577.2) were included. Diagnosis of pancreatic malignancy was confirmed through cross-reference with a prospectively maintained internal KPSC cancer registry. For cost analysis portion of the study, the cost of EUS was based on 2017 Medicare national average payment for hospital out-patient procedure (CPT® 43238). For GI and surgery consultations, CPT® codes 99201-99205 were used. Extrapolation of the result to the US population was based on the estimation of the incidence of pancreatic cyst in the US being between 3% and 15%, percentage increasing with age, according to the American Gastroenterological Association Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Neoplastic Pancreatic Cysts. Lower end of this range (3%) was used in our analysis to err on the side of a conservative estimate.

2558 (1157 pre- and 1401 post-algorithm) received a new diagnosis of PCN in the study period. A smaller percentage of PCNs resulted in EUS after the implementation of the algorithm (pre- 45.5% vs post- 34.8%, P < 0.001). A smaller proportion of patients were referred for GI (pre- 65.2% vs post- 53.3%, P < 0.001) and surgery consultations (pre- 24.8% vs post- 16%, P < 0.001) for PCN after the implementation. The incidence rate of pancreatic cancer after diagnosis of PCN (between the time of PCN diagnosis and May 1, 2017 or end of KPSC membership), excluding those that were diagnosed at the time of initial work-up, was 2.41 per 1000-person years (95%CI: 1.16-4.44) for pre-algorithm and 2.42 per 1000-person years (95%CI: 1.04-4.77) for post-algorithm (P = 0.4943). After the implementation, cost of diagnostic care was reduced by 24%, 18%, and 36% for EUS, GI, and surgery consultations, respectively. Total cost saving was 24%. If we assume that the incidence of pancreatic cysts in KPSC is 1000 (estimate based on our search using ICD-9), total annual cost saving would be $194696 ($584088 during the entire study period), $173874 for EUS, $9805 for GI consultation, and $11018 for surgery consultation. However, this incidence may be significantly underestimated; KPSC incidence using the lower end of the US incidence (3%, range 3%-15%) would be 98040 given that KPSC adult population is 3268000. Using this figure as the incidence, total cost saving would increase to $19 Million ($17 Million for EUS, $1 Million for GI consultations, and $1 Million for surgery consultations). These findings were then extrapolated to the national level. The US population estimate as of July 1st, 2017 was 325719178 with 251455205 adults. Using the 3% incidence rate, the cost saving as a result of such algorithm implementation would be $1.49 Billion ($1.34 Billion for EUS, $72 Million for GI consultations, and $81Million for surgery consultations).

Our study is unique in that it examines that economic effect of adopting a pancreatic cyst management guideline in an effective way within a healthcare system. Although there have been numerous studies looking at the clinical effect of the guidelines, there has been a paucity of studies dealing with the change in the practice/referral pattern. Our study demonstrated that the dissemination of an algorithm for pancreatic cyst management in such a manner increased the threshold for referrals for intervention and workup, possibly due to increasing the confidence level of physicians ordering imaging studies in managing PCNs, resulting in significant cost savings without compromising patient care. As stated above, if the findings of this study were extrapolated to the US national level, the cost saving as a result of such algorithm implementation could be $1.49 Billion. There would be a much stronger impact if the recommendations were applied to clinical practice worldwide.

Although our study presents a strong economic message in a relatively short study period of 36 mo and proves that there was no difference in the pancreatic cancer rate between the two groups after following the patients for a longer period until May 1, 2017 (60 mo from the beginning of the study period), we realize that this is not a long enough follow up timeframe to examine the natural course of PCNs. While the aim of the study was to show the cost savings that could result from the change in clinical practice following the dissemination of such an algorithm and not necessarily to show how the algorithm can improve patient outcome, we do realize the importance of studies that address the long-term outcome of not only the PCN algorithm(s) but also the natural course of PCNs themselves. This type of long-term study should be the direction of future research of PCNs.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Crino S, Grizzi F, Gong JS S- Editor: Wang XJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Megibow AJ, Baker ME, Gore RM, Taylor A. The incidental pancreatic cyst. Radiol Clin North Am. 2011;49:349-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | de Jong K, Nio CY, Hermans JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Gouma DJ, van Eijck CH, van Heel E, Klass G, Fockens P, Bruno MJ. High prevalence of pancreatic cysts detected by screening magnetic resonance imaging examinations. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:806-811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 367] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 25.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tang RS, Weinberg B, Dawson DW, Reber H, Hines OJ, Tomlinson JS, Chaudhari V, Raman S, Farrell JJ. Evaluation of the guidelines for management of pancreatic branch-duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:815-819; quiz 719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Klibansky DA, Reid-Lombardo KM, Gordon SR, Gardner TB. The clinical relevance of the increasing incidence of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:555-558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jacobson BC, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila RE, Egan J, Hirota WK, Leighton JA, Qureshi W, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ. ASGE guideline: The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and the management of cystic lesions and inflammatory fluid collections of the pancreas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:363-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, Yamaguchi K, Yamao K, Matsuno S; International Association of Pancreatology. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2006;6:17-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1539] [Cited by in RCA: 1440] [Article Influence: 75.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Khalid A, Brugge W. ACG practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2339-2349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tanaka M, Fernández-del Castillo C, Adsay V, Chari S, Falconi M, Jang JY, Kimura W, Levy P, Pitman MB, Schmidt CM. International consensus guidelines 2012 for the management of IPMN and MCN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2012;12:183-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1612] [Article Influence: 124.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1218-1226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Farrell JJ, Fernández-del Castillo C. Pancreatic cystic neoplasms: management and unanswered questions. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1303-1315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Munigala S, Gelrud A, Agarwal B. Risk of pancreatic cancer in patients with pancreatic cyst. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;84:81-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nagai K, Doi R, Ito T, Kida A, Koizumi M, Masui T, Kawaguchi Y, Ogawa K, Uemoto S. Single-institution validation of the international consensus guidelines for treatment of branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:353-358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pelaez-Luna M, Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Takahashi N, Clain JE, Levy MJ, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Topazian MD, Vege SS. Do consensus indications for resection in branch duct intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm predict malignancy? A study of 147 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1759-1764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 205] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Scheiman JM, Hwang JH, Moayyedi P. American gastroenterological association technical review on the diagnosis and management of asymptomatic neoplastic pancreatic cysts. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:824-848.e22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tanaka M, Fernández-Del Castillo C, Kamisawa T, Jang JY, Levy P, Ohtsuka T, Salvia R, Shimizu Y, Tada M, Wolfgang CL. Revisions of international consensus Fukuoka guidelines for the management of IPMN of the pancreas. Pancreatology. 2017;17:738-753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 868] [Cited by in RCA: 1145] [Article Influence: 143.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |