Published online Oct 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i12.559

Peer-review started: July 2, 2018

First decision: July 29, 2018

Revised: August 21, 2018

Accepted: August 27, 2018

Article in press: August 28, 2018

Published online: October 26, 2018

Processing time: 118 Days and 22.2 Hours

Generally, hysteroscopy is not appropriate for pregnant women without an indication. What if a patient undergoes hysteroscopy accidentally during the early gestational period? We here report a rare case of a woman who continued pregnancy after a diagnostic hysteroscopy was performed in early pregnancy and delivered a healthy baby. The patient had a history of infertility and oligomenorrhea, probably due to a previous induced abortion. A hysteroscopy was performed after the end of her “menstruation” for assessment of her uterine cavity. Early pregnancy, instead of the expected intrauterine adhesions, was suspected, and the procedure was immediately ceased. Subsequent tests confirmed the diagnosis of pregnancy. She had a full-term delivery by elective caesarean section. The success of this case was attributed to the use of vaginoscopic techniques in hysteroscopy and correct judgment and decision-making during the procedure. This case report provides some useful methods and experience that might be helpful when a similar situation occurs in clinical practice.

Core tip: An intended pregnancy without any suspected abnormalities is a contraindication for hysteroscopy. Although hysteroscopy is often scheduled in the follicular phase, potential pregnancy is unavoidable, even in patients with a history of infertility. When the image under hysteroscopy is not so typical for a doctor to recognize and immediately confirm a state of pregnancy, gentle and careful operation along with appropriate measures can benefit the patients to the largest extent.

- Citation: Zhao CY, Ye F. Live birth after hysteroscopy performed inadvertently during early pregnancy: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(12): 559-563

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i12/559.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i12.559

Hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard for the evaluation of the uterine cavity[1]. Although diagnostic hysteroscopy is a technique with minimal invasiveness, it remains a contraindication for viable pregnancy. Whether the technique itself, the distention medium or the pressure used during the procedure produces harmful effects on early pregnancy remains unknown. Since Assaf et al[2] reported live births after the removal of intrauterine devices by hysteroscopy during early pregnancy, some similar cases have been reported on this issue. However, most cases had a definitive diagnosis of pregnancy beforehand, while hysteroscopy was only used as a treatment. Some cases occurred during the implantation period, and diagnosis of pregnancy was confirmed a few weeks after hysteroscopy. Here, we report a rare case of a woman whose pregnancy was unexpectedly identified during diagnostic hysteroscopy and the procedure did not disturb the pregnancy.

A 30-year-old woman was referred to our outpatient department because of hypomenorrhea and secondary infertility after an induced abortion performed three years previously. She was suspected to have intrauterine adhesions (IUAs) according to her symptoms and clinical history. She had regular menstrual cycles, and her past medical history was unremarkable. No abnormal signs were found by pelvic examination. A transvaginal sonography (TVS) was performed 20 d prior to hysteroscopy, and the result was normal.

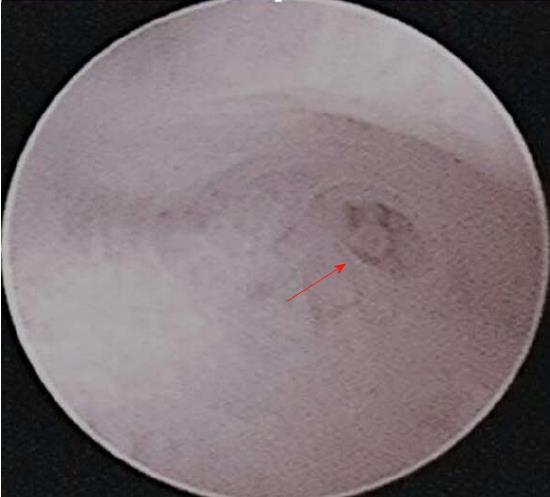

The patient underwent hysteroscopy 4 d after the end of her “last menstrual period” (it was actually menstrual-like bleeding). A history of abstinence during the previous month was provided by the patient (it was actually a false medical history). We used a 4.5-mm rigid hysteroscope for examination in the absence of speculum, tenaculum, Pozzi forceps and cervical dilation. Vaginoscopic technique was adopted to reduce the pain generated by use of the above instruments. No anesthesia or analgesia was administered. The distention medium used was normal saline at room temperature. Diagnostic hysteroscopy revealed thickened and decidualized endometrium, but no obvious gestational sac was seen in the uterine cavity (Figure 1). Left tubal ostium was found (Figure 2), while the right tubal ostium could not be observed. Since pregnancy was suspected at that moment, we ceased the examination soon after.

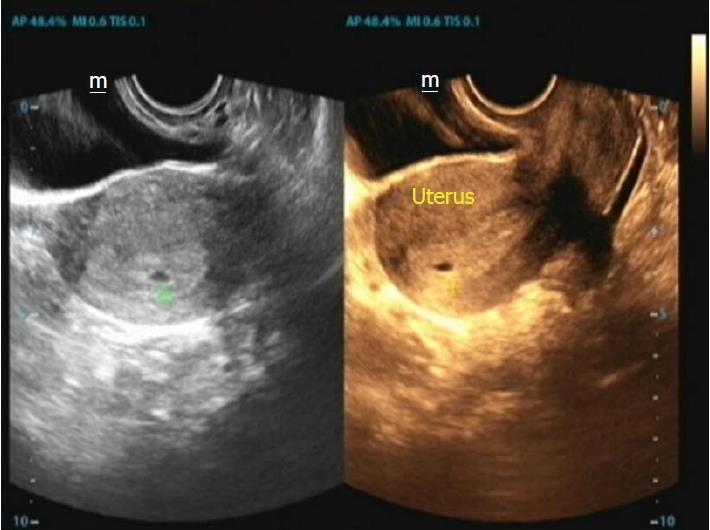

Urine pregnancy test after hysteroscopy was positive. Since the pregnancy was so desired by the patient and her husband, serum human chorionic gonadotropin and progesterone were tested, and the results were 4917.67 mIU/mL and 54.1 nmol/L, respectively. A transvaginal ultrasound showed a 3-mm gestational sac in the uterine cavity (Figure 3). Minimal vaginal bleeding occurred in the following week. On a subsequent visit half a month later, the fetal heart was successfully detected by transvaginal ultrasound (Figure 4). Her pregnancy continued uneventfully until full term. An elective cesarean section was performed, and she gave birth to a normal boy weighing 3150 g. The woman has been followed up. The baby is now 11 mo old, and is as normal as other babies of the same age.

Termination of pregnancy such as induced abortion is regarded as one of the most important reasons for IUA[3]. Although clinical history, along with patient’s manifestations and auxiliary examination like TVS, are helpful in the diagnosis of IUA, hysteroscopy is considered the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment of IUA. In general, hysterosalpingography (HSG), sonohysterography, TVS, and hysteroscopy are the most commonly used methods for detecting intrauterine lesions associated with infertility. However, many articles published have made the comparison among these techniques and have concluded that hysteroscopy is of higher value on the diagnosis of intrauterine lesions in infertile women[4-6]. With the progress of technology, hysteroscopy today is a simple, safe, and cost-effective outpatient procedure for diagnosis and treatment of intrauterine lesions.

Viable intrauterine pregnancy is a contraindication for hysteroscopy[1]. The procedure may cause infections or lead to abortion. A pregnancy test is regarded as a selective test but not a routine one before the procedure. It often depends on the complaints and clinical history of the patient[7]. In our case, the pregnancy test was not performed prior to hysteroscopy because the patient presented with “normal menstrual cycles”, a history of abstinence during the preceding month and a long duration of infertility. We inadvertently performed hysteroscopy on the woman during her early pregnancy. However, the procedure, which was carried out with normal saline as the distention medium, did not disrupt the gestation. The woman eventually had a successful delivery.

Live birth outcomes have been reported in some cases when using invasive measures such as hysteroscopy, HSG, laparoscopy and chromotubation during pregnancy.

In 1992, Assaf et al[2] reported successful pregnancy outcomes after removal of intrauterine devices by CO2 hysteroscopy during early pregnancy. As was reported, 31 of 50 patients achieved full-term pregnancy after the procedure[2]. Last year, Cohen et al[8] reported that seven pregnant patients who had undergone removal of intrauterine devices by hysteroscopy delivered at term without obstetric complications. Along with these two articles, some other similar articles have confirmed the effectiveness and safety of hysteroscopy in removing the intrauterine devices during pregnancy. Besides, McCarthy et al[9] reported a case that a levonorgestrel intrauterine system was successfully removed by ultrasound-guided hysteroscopy during early pregnancy. Moreover, despite exposure to the levonorgestrel intrauterine system during first-trimester, the female baby was normal[9]. AL-Mizyen et al[10] reported a live birth after bilateral ovarian diathermy and hysteroscopy performed during early pregnancy. Erenus and Sezen[11] described a case of ongoing pregnancy in a woman who underwent hysteroscopy during the implantation phase. Justesen et al[12] reported four cases of HSG performed inadvertently during early pregnancy. One of them had a live birth[12]. Kuo et al[13] reported a case of live birth after inadvertently performing HSG during early pregnancy. After seven years of follow-up by the authors, the growth and development of the child was found to be normal[13]. Opsahl[14] reported three cases of full-term deliveries after laparoscopy and chromotubation performed during the implantation phase. Dwivedee and Banfield reported a live birth after inadvertent hysteroscopy and laparoscopy in a patient of uterus didelphys in early pregnancy[15]. Last year, Pontré and McElhinney reported a live birth occurring post-radical laparoscopic excision of endometriosis, hysteroscopy, curettage and test of tubal patency during the early implantation phase[16]. All of these cases indicate that early pregnancy is invulnerable most of the time. However, images under hysteroscopy during early viable pregnancy are rare.

Although early pregnancy is invulnerable, it may become very fragile due to an inappropriate decision made during invasive procedures. Sometimes it is difficult for a doctor to make an accurate diagnosis when such uncommon images are visualized under hysteroscopy. It needs to be differentiated from endometrial lesions. Instead of immediate biopsy or even dilation and curettage, performing further confirming tests is the optimal choice. In our case, we ceased the procedure at once and prescribed a urine pregnancy test to confirm the tentative diagnosis of early pregnancy. However, instead of discontinuing the hysteroscopic procedure, the best option would be to pause the procedure, collect a urine sample and test it for urinary beta human chorionic gonadotropin at the time of surgery.

Hysteroscopy is often scheduled in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle. However, performing hysteroscopy inadvertently during an unexpected early pregnancy seems inevitable. Menstrual-like bleeding may be regarded as normal, especially in oligomenorrhea. To avoid making mistakes, many units now rely on a history of abstinence or the use of contraception in the preceding month. As in our case, a preoperative discussion between doctor and the patient regarding contraception and unprotected sexual intercourse was done 2 mo prior to the procedure. However, the patient denied any history of sexual intercourse during the previous month. She provided a false history in order to not wait another month. This case also emphasizes the importance of effective and successful communication. Pregnancy test before hysteroscopy is regarded to not cost-effective and is not recommended for all patients[7]. However, according to Herr et al[17], one of 410 women presenting for HSG was found to have an unsuspected early pregnancy, which was detected with a point-of-care urine pregnancy test. The authors suggested a routine pregnancy test before HSG[17]. In the same way, consideration should be given to routine pregnancy testing of women with infertility before hysteroscopy because scheduling on the basis of menstrual cycle can be unreliable.

The case highlights the importance that hysteroscopy should be performed with caution at any time. An unexpected situation as in this case should always be kept in mind in order to avoid disturbance of a potential normal pregnancy during invasive procedures. Even a patient with a long history of infertility may acquire pregnancy at any time.

In addition, vaginoscopic technique is very important in such a case. It can reduce the pain caused by use of a speculum and cervix dilation, which may induce a miscarriage. Vaginoscopy is now recommended as a standard technique for outpatient hysteroscopy[1].

In conclusion, we report a case of live birth after hysteroscopy was inadvertently performed during early pregnancy. Although hysteroscopy is often scheduled in the follicular phase, potential pregnancy is unavoidable. Gentle and careful operation, timely identification of images under hysteroscopy and taking appropriate measures can benefit the patients to the largest extent.

It is inevitable to encounter a potential pregnancy under hysteroscopy during the follicular phase. Gentle and careful operation, timely identification of images under hysteroscopy and taking appropriate measures can benefit the patients to the largest extent.

Early pregnancy.

Endometrial lesions.

Urine pregnancy test confirmed the diagnosis of pregnancy.

Thickened and decidualized endometrium suggested a suspected diagnosis of early pregnancy.

A follow-up of the patient until full-term delivery, without treatment or drug used.

A few cases have been published on this issue. However, most of the patients in those cases underwent hysteroscopy during implantation phase and the images under hysteroscopy were normal. However, no hysteroscopic images were provided in these cases.

The levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG IUS) is a T-shaped, plastic, contraceptive IUS that releases the progestin hormone levonorgestrel into the uterus at a dose of 20 μg/d for up to five years. LNG IUS prevents pregnancy by thickening cervical mucus, inhibiting sperm motility, and suppressing the growth of the uterine wall.

Consideration should be given to routine pregnancy testing of women with infertility before hysteroscopy, because scheduling on the basis of menstrual cycle dates can be unreliable. It is very important to perform hysteroscopy gently and carefully.

We acknowledge Dr. Rong Zi for her inspiration and useful suggestions in preparation of this manuscript.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2013), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Iliescu EL, Partsinevelos G, Schulten HJ S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | Salazar CA, Isaacson KB. Office Operative Hysteroscopy: An Update. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:199-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Assaf A, Gohar M, Saad S, el-Nashar A, Abdel Aziz A. Removal of intrauterine devices with missing tails during early pregnancy. Contraception. 1992;45:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hooker A, Fraenk D, Brölmann H, Huirne J. Prevalence of intrauterine adhesions after termination of pregnancy: a systematic review. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2016;21:329-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Taşkın EA, Berker B, Ozmen B, Sönmezer M, Atabekoğlu C. Comparison of hysterosalpingography and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of the uterine cavity in patients undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Fertil Steril. 2011;96:349-352.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | akas P, Hassiakos D, Grigoriadis C, Vlahos N, Liapis A, Gregoriou O. Role of hysteroscopy prior to assisted reproduction techniques. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:233-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wadhwa L, Rani P, Bhatia P. Comparative Prospective Study of Hysterosalpingography and Hysteroscopy in Infertile Women. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2017;10:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Deffieux X, Gauthier T, Ménager N, Legendre G, Agostini A, Pierre F. [Prevention of the complications related to hysteroscopy: guidelines for clinical practice]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2013;42:1032-1049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cohen SB, Bouaziz J, Bar-On A, Schiff E, Goldenberg M, Mashiach R. In-office Hysteroscopic Extraction of Intrauterine Devices in Pregnant Patients Who Underwent Prior Ultrasound-guided Extraction Failure. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:833-836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McCarthy EA, Jagasia N, Maher P, Robinson M. Ultrasound-guided hysteroscopy to remove a levonorgestrel intrauterine system in early pregnancy. Contraception. 2012;86:587-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | AL-Mizyen E, Barnick CG, Grudzinskas JG. Early pregnancy is elusive and robust. Early Pregnancy. 2001;5:144-148. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Erenus M, Sezen D. Ongoing pregnancy in a woman who inadvertently underwent office hysteroscopy during early pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 2005;83:211-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Justesen P, Rasmussen F, Andersen PE Jr. Inadvertently performed hysterosalpingography during early pregnancy. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1986;27:711-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kuo CH, Lin HC, Chang MH. Outcome of inadvertently performed hysterosalpingography during early pregnancy---7 years after birth. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;47:463-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Opsahl MS. Outcome of pregnancy after laparoscopy and chromotubation during cycles of conception: a report of three cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:902-903. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dwivedee K, Banfield PJ. A case report of inadvertent hysteroscopy and laparoscopy in a patient of uterus didelphys with early pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;27:638-639. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pontré JC, McElhinney B. Early intrauterine pregnancy during major surgery: the importance of preoperative assessment and advice. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018:pii: bcr-2017-222731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Herr K, Moreno CC, Fantz C, Mittal PK, Small WC, Murphy F, Applegate KE. Rate of detection of unsuspected pregnancies after implementation of mandatory point-of-care urine pregnancy testing prior to hysterosalpingography. J Am Coll Radiol. 2013;10:533-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |