Published online Oct 26, 2018. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v6.i12.554

Peer-review started: July 2, 2018

First decision: July 24, 2018

Revised: August 3, 2018

Accepted: August 28, 2018

Article in press: August 28, 2018

Published online: October 26, 2018

Processing time: 119 Days and 12.5 Hours

Linitis plastica is a rare condition showing circumferentially infiltrating intramural anaplastic carcinoma in a hollow viscus, resulting in a tissue thickening of the involved organ as constricted, inelastic, and rigid. While most secondary rectal linitis plastica (RLP) is caused by metastasis from stomach, breast, gallbladder, or bladder cancer, we report an extremely rare and unique case of secondary RLP due to prostate cancer with computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, including diffusion weighted imaging (DWI). A 78-year-old man presented with approximately a 2-mo history of constipation and without cancer history. On sigmoidoscopy, there was a luminal narrowing and thickening of rectum with mucosa being grossly normal in its appearance. On contrast-enhanced CT, marked contrast enhancement with wall thickening of rectum was noted. On pelvic MRI, rectal wall thickening showed a target sign on both T2-weighted imaging and DWI. A diffuse infiltrative lesion was suspected in the prostate gland based on low signal intensity on T2-weighted imaging and restricted diffusion. A transanal full-thickness excisional biopsy revealed metastasis from a prostate adenocarcinoma invading the submucosa to the muscularis propria consistent with metastatic RLP. We would like to emphasize the CT and MRI findings of metastatic RLP due to prostate cancer.

Core tip: Secondary rectal linitis plastica (RLP) from prostate cancer is extremely rare. A target sign on T2-weighted imaging and diffusion weighted imaging is characteristic for RLP. The presence of elevated serum prostate specific antigen, T2 low signal intensity, and low apparent diffusion coefficient value lesion on prostate should raise the suspicion of secondary RLP from prostate adenocarcinoma. For confirmative diagnosis, full-thickness excisional biopsy is required due to its characteristic mucosal sparing.

- Citation: You JH, Song JS, Jang KY, Lee MR. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings of metastatic rectal linitis plastica from prostate cancer: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2018; 6(12): 554-558

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v6/i12/554.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v6.i12.554

Linitis plastica refers to a circumferential intramural tumor infiltration of a hollow viscus, generating a desmoplastic reaction that result in a rigid shrunken viscus with thickened walls[1,2]. The stomach is the most commonly involved organ, although the small intestine, colon, and rectum also can be involved. This process can be either primary or secondary to metastasis, and shows characteristic mucosal sparing while involving only the submucosa and muscularis propria[3]. Primary rectal linitis plastica (RLP), also known as signet ring cell carcinoma, is a very rare disease affecting less than 1% of colorectal cancer patients, while secondary RLP from stomach, breast, gallbladder, or bladder cancer occurs more frequently and has been reported previously[4-8]. Due to the widespread use of pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in rectal cancer evaluation, some characteristic findings have been suggested, such as a concentric ring pattern or target sign on T2-weighted imaging[7,9].

Here we describe an extremely rare and unique case of metastatic RLP due to prostate cancer with findings of computed tomography (CT) and MRI including diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI). To the best of our knowledge, metastatic RLP as a first manifestation of prostate cancer with both CT and MRI findings has never been reported.

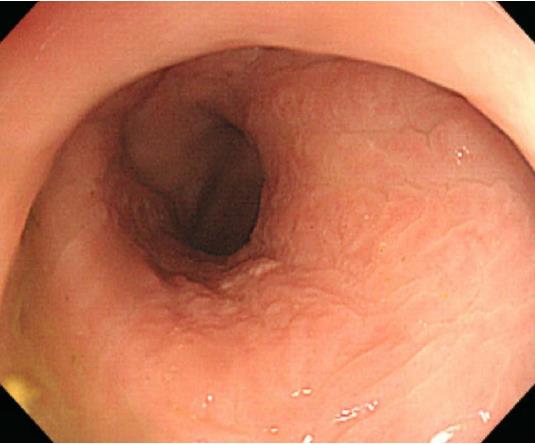

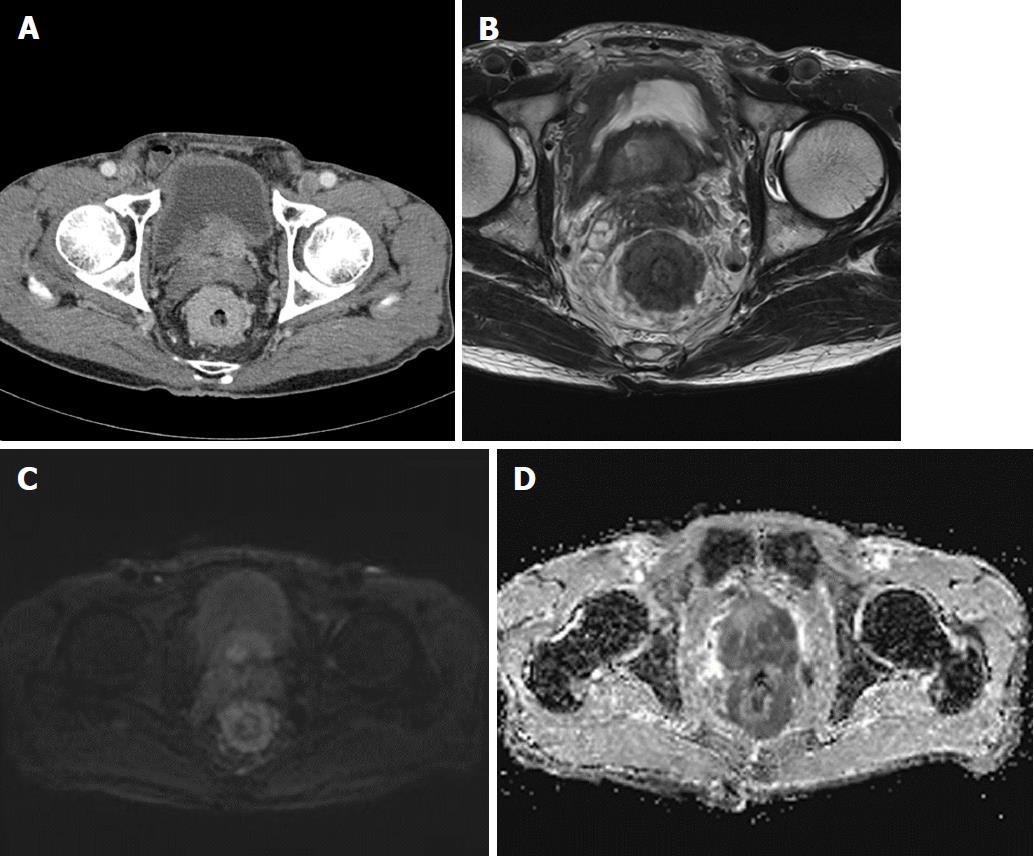

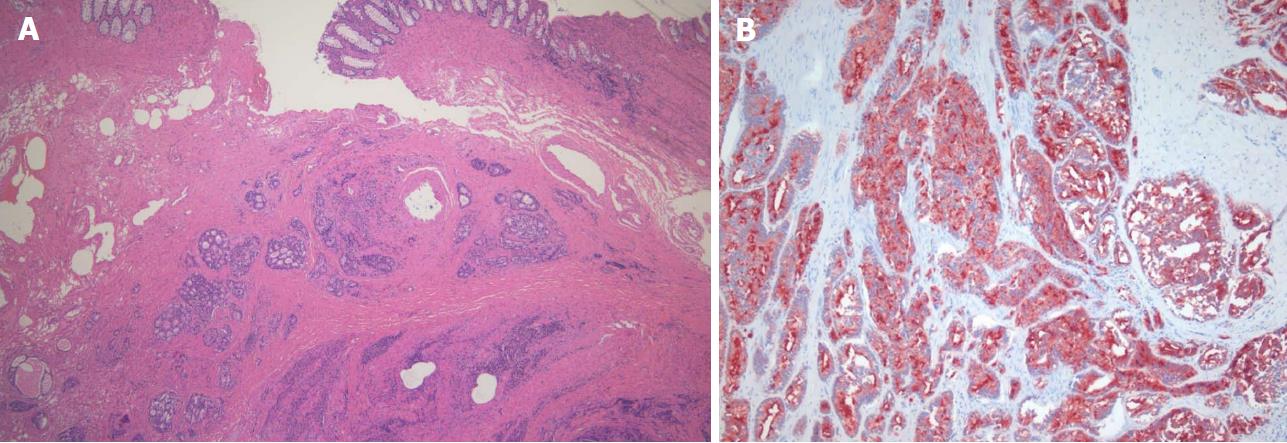

A 78-year-old man presented with a 2-mo history of constipation and thinning of stool caliber. He had a medical history of benign prostatic hyperplasia and hypertension. Laboratory findings were unremarkable, except the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level was elevated to 409 ng/mL. Digital rectal examination revealed luminal narrowing of rectum with rigidity. Sigmoidoscopy revealed luminal narrowing of the mid to lower rectum, with grossly indurated, non-ulcerated mucosa (Figure 1). On contrast-enhanced CT, rectal wall thickening (mean thickness, 1.3 cm) with marked homogeneous enhancement and mild perirectal fat stranding was demonstrated (Figure 2A). Based on these observations, a submucosal spreading tumor was suspected, and pelvic MRI was performed for further evaluation. Coronal and sagittal T2-weighted imaging showed concentric thickening of the mid to lower rectum, about 6-7 cm in length, with stratification and perirectal fascial thickening. On axial T2-weighted imaging, the rectum showed three-layered wall thickening, with the middle layer showing isointensity and the inner and outer layers showing hypointensity (Figure 2B). On DWI, the lesion also revealed a concentric ring pattern or target sign, with the middle layer showing restricted diffusion while the inner and outer layers showed no restriction (Figure 2C). The prostate gland was enlarged and a diffuse infiltrative lesion was suspected showing low SI on both T1- and T2-weighted images with a low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value (Figure 2D). There was also low SI on both T1- and T2-weighted images of the left seminal vesicle, and both external iliac lymph nodes were enlarged and round shaped. Positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) revealed diffuse wall thickening of the mid to lower rectum without significant 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose (FDG) uptake. There was no other pathologic site with abnormal FDG uptake. For both confirmative diagnosis and symptom relief, intraoperative transanal full-thickness excisional biopsy with loop sigmoid colostomy formation was performed. The pathologic examination revealed metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma invading the submucosa to muscularis propria with a positive PSA stain and negative for CDX2, consistent with metastatic RLP due to prostate cancer (Figure 3). Gleason score of biopsy specimen was 9 (4 + 5). The patient underwent Luphere Depot (leuprolide acetate; a synthetic nonapeptide analog of naturally occurring gonadotropin-releasing hormone; used in the palliative treatment of advanced prostatic cancer) treatment and the PSA level decreased to normal without any adverse event. The patient has had no symptoms and his PSA levels have been normal for 2 years now.

Linitis plastica is characterized by diffuse proliferation of connective tissue of a hollow organ wall by infiltrating tumor cells. This term was first introduced by Brinton W meaning the “leather bottle” shape of the stomach, and was later extended to other hollow organs to be constricted, inelastic, and rigid aspects of the wall[10]. Primary RLP is very rare, while secondary RLP is more common, with some CT and MRI findings available for secondary RLP from breast and bladder cancer[11-14]. To the best of our knowledge, there were only 2 case reports of secondary RLP from prostatic adenocarcinoma with only endoscopic ultrasonographic findings available[5,15]. Therefore, this is the first case report to describe the CT and MRI findings of secondary RLP from prostatic adenocarcinoma.

Ha et al[14] previously reported CT features of metastatic RLP in 22 patients. Primary cancer included 18 gastric cancer patients, 1 patient with bladder cancer (transitional cell carcinoma), 1 patient with ovarian cancer (serous cystadenocarcinoma), 1 patient with cervical cancer (squamous cell carcinoma), and 1 patient with colon cancer. Twenty patients (90%) had more than 5 cm in length of rectal involvement. In 19 patients (86%), rectal wall thickening (mean, 1.6 cm) extended to the lower rectum close to the level of the anal verge. In 6 patients (27%), the rectum showed three zones of layered wall thickening (target sign): hyperattenuated inner zone, hypoattenuated middle zone, and hyperattenuated outer zone. Of the 16 patients without the target sign, 3 showed strong contrast enhancement in the rectum. Our patient also showed marked rectal wall thickening with its length involving more than 5 cm, and showed marked contrast enhancement without a target sign on CT.

In the present case, T2-weighted imaging revealed doubled-layered concentric thickening of the rectal wall with an isointense middle layer and hypointense inner and outer layers representing a target sign. Based only on initial CT images, our first impression was infiltrative malignancy, such as lymphoma involving rectum, since smooth overlying mucosal thickening and concentric narrowing in the rectum was seen. However, there were only two lymph node enlargements at both external iliac chains, which is an unusual finding of lymphoma. Furthermore, other conditions such as chronic radiation colitis may contribute to rectal narrowing with circumferential wall thickening, but the patient did not have a history of pelvic malignancy or radiation therapy. On MRI, the involved rectum demonstrated a target sign on both T2-weighted imaging and DWI, which is considered as one of specific finding for diagnosing RLP[12]. In addition, an infiltrative lesion with a low signal intensity on both T1- and T2-weighted imaging accompanied by heterogenous enhancement and low ADC values were revealed in the enlarged prostate gland. On PET/CT, there was no evidence of other sites with abnormal FDG uptake suggestive of metastasis or another primary cancer site. Based on these imaging findings and elevated serum PSA level, we suspected secondary RLP from prostatic adenocarcinoma.

In reviewing the literature, a characteristic pathologic finding of linitis plastica is an exuberant desmoplastic response that prominently elicits tumor cells and its product in submucosa and subserosa[2,16,17]. It is difficult to diagnose on endoscopy in most cases because of its characteristic mucosal sparing. Therefore, cross sectional imaging findings may be helpful to guide early and precise diagnosis of RLP, whether primary or secondary. When there is a concentric rectal wall thickening with a layered appearance resembling a target sign, an experienced radiologist would check the patient’s history to make a differential diagnosis such as inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease), pelvic radiation (radiation proctitis), or primary malignancy (secondary RLP). If the patient has no such history, the possibility of either primary or secondary RLP should be raised, and workup for primary cancer detection is necessary.

In the present case, there was a target sign on MRI which also revealed a similar pathologic finding on full-thickness excisional biopsy, in which metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma invaded the submucosa and muscularis propria while sparing the mucosal layer. Although the direct comparison of whole rectum and MRI could not be made, we assume that this pathologic finding on the biopsy specimen was well correlated with T2-weighted imaging and DWI showing a concentric ring pattern or target sign, which represents a double-layered wall thickening. On DWI, diffusion restriction can be caused by highly cellular tissue (e.g., tumor tissues), intracellular edema, increased viscosity, tortuous extracellular space (e.g., fibrosis with or without granulation tissue) and increased densities associated with hydrophobic cellular membranes[18]. We assume that in RLP, a tumor infiltrating the submucosa and muscularis propria associated with fibrosis and desmoplastic reaction would correlate with restricted diffusion in the middle zone, depicted as a target sign on DWI. The target sign could be a result of the normal zonal anatomy becoming more pronounced due to the invasion of an infiltrative tumor with fibrosis into the submucosa and on the longitudinal and circular layers of the proper muscle. In spite of substantial mural infiltration seen with RLP, the proper muscle layer is usually conserved, which may further explain the target sign[14]. Further studies with whole rectal specimens to make precise correlations with MRI are needed.

In conclusion, when there is a long segment of circumferential rectal wall thickening with luminal narrowing, a target sign on T2-weighted imaging and DWI is suggestive of RLP. Therefore, knowledge of a patient’s primary cancer history at other organs and the secondary findings in abdominal organs can suggest the possibility of secondary RLP rather than primary RLP.

A 78-year-old male patient was admitted because of a 2-mo history of constipation and luminal narrowing of the rectum on sigmoidoscopy.

A submucosal spreading tumor of the rectum, such as lymphoma, was suspected.

Chronic radiation colitis, inflammatory bowel disease.

Elevated serum prostate specific antigen, suggesting prostate cancer.

Findings from pelvic magnetic resonance imaging led to a diagnosis of secondary linitis plastica of the rectum due to prostate cancer.

Metastatic rectal linitis plastica (RLP) due to prostate cancer.

Loop sigmoid colostomy for immediate symptom relief and hormone therapy for prostate cancer.

Metastatic RLP due to prostate is extremely rare, and this is the first case report to describe both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings.

There are no uncommon terms used in this manuscript.

Although rare, careful evaluation with a high suspicion for other sites of malignancy, including the prostate, is needed when RLP is suspected on imaging studies.

CARE Checklist (2013) statement: This manuscript has completed the CARE Checklist (2013).

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Balta AZ, Rubbini M, Kir G S- Editor: Dou Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Song H

| 1. | Wei SC, Su WC, Chang MC, Chang YT, Wang CY, Wong JM. Incidence, endoscopic morphology and distribution of metastatic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:827-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fernet P, Azar HA, Stout AP. Intramural (tubal) spread of linitis plastica along the alimentary tract. Gastroenterology. 1965;48:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 3. | el Absi M, Elouannani M, Elmdarhri J, Echarrab M, el Amraoui M, el Alami F, Benchekroun A, Errougani A, Chakoff R, Zizi A. [Primary linitis plastica of the rectum]. Rev Med Liege. 2002;57:10-12. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Taal BG, den Hartog Jager FC, Steinmetz R, Peterse H. The spectrum of gastrointestinal metastases of breast carcinoma: II. The colon and rectum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:136-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bhutani MS. EUS and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration for the diagnosis of rectal linitis plastica secondary to prostate carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:117-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yusuf TE, Levy MJ, Wiersema MJ. EUS features of recurrent transitional cell bladder cancer metastatic to the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:314-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dresen RC, Beets GH, Vliegen RF, Creytens DH, Beets-Tan RG. Linitis plastica of the rectum secondary to bladder carcinoma: a report of two cases and its MR features. Br J Radiol. 2008;81:e249-e251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gleeson FC, Clain JE, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Wang KK, Wiersema MJ, Zhang L, Levy MJ. Secondary linitis plastica of the rectum: EUS features and tissue diagnosis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:591-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Boustani J, Kim S, Lescut N, Lakkis Z, de Billy M, Arbez-Gindre F, Jary M, Borg C, Bosset JF. Primary Linitis Plastica of the Rectum: Focus on Magnetic Resonance Imaging Patterns and Treatment Options. Am J Case Rep. 2015;16:581-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Laufman H, Saphir O. Primary linitis plastica type of carcinoma of the colon. AMA Arch Surg. 1951;62:79-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fahl JC, Dockerty MB, Judd ES. Scirrhous carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1960;111:759-766. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Rudralingam V, Dobson MJ, Pitt M, Stewart DJ, Hearn A, Susnerwala S. MR imaging of linitis plastica of the rectum. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:428-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gollub MJ, Schwartz MB, Shia J. Scirrhous metastases to the gastrointestinal tract at CT: the malignant target sign. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;192:936-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ha HK, Jee KR, Yu E, Yu CS, Rha SE, Lee IJ, Yun HJ, Kim JC, Park KC, Auh YH. CT features of metastatic linitis plastica to the rectum in patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:463-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dumontier I, Roseau G, Palazzo L, Barbier JP, Couturier D. Endoscopic ultrasonography in rectal linitis plastica. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:532-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dixon CF, Stevens GA. Carcinoma of linitis plastica type involving the intestine. Ann Surg. 1936;103:263-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Andersen JA, Hansen BF. Linitis plastica of the colon and rectum: report of two cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 1972;15:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Szafer A, Zhong J, Anderson AW, Gore JC. Diffusion-weighted imaging in tissues: theoretical models. NMR Biomed. 1995;8:289-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |