Published online Aug 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.340

Peer-review started: December 26, 2016

First decision: February 17, 2017

Revised: April 21, 2017

Accepted: May 12, 2017

Article in press: May 15, 2017

Published online: August 16, 2017

Processing time: 236 Days and 13.7 Hours

Pseudotumoral cerebellitis in childhood is an uncommon presentation of cerebellitis mimicking a brain tumor. It often follows an inflammatory or infectious event, particularly due to varicella virus. Patients could have a wide clinical spectrum on presentation. Some patients may be asymptomatic or present at most with mild cerebellar signs, whereas others may suffer severe forms with brainstem involvement and severe intracranial hypertension mimicking tumor warranting surgical intervention. Imaging techniques especially multimodal magnetic resonance imaging represent an interesting tool to differentiate between posterior fossa tumors and acute cerebellitis. We describe a case of pseudotumoral cerebellitis in a 6-year-old girl consequent to mumps infection and review the literature on this rare association.

Core tip: Pseudotumoral cerebellitis in childhood is an uncommon presentation of cerebellitis mimicking a brain tumor. It often follows an inflammatory or infectious event, particularly due to varicella virus. Patients could have a wide clinical spectrum on presentation. Imaging techniques especially multimodal magnetic resonance imaging represent an interesting tool to differentiate between posterior fossa tumors and acute cerebellitis. We describe a case of pseudotumoral cerebellitis in a 6-year-old girl consequent to mumps infection and review the literature on this rare association.

- Citation: Ajmi H, Gaha M, Mabrouk S, Hassayoun S, Zouari N, Chemli J, Abroug S. Pseudotumoral acute cerebellitis associated with mumps infection in a child. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(8): 340-343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i8/340.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i8.340

Acute cerebellitis is usually a benign disease[1]. Patients could have a wide clinical spectrum on presentation. Some patients may be asymptomatic[2] or present at most with mild cerebellar signs, whereas others may suffer severe forms related to brainstem compression and severe intracranial hypertension mimicking tumor warranting surgical intervention[3]. The diagnosis and the management of these pseudotumoral forms represent a challenge for clinicians and radiologists to distinguish acute cerebellitis from posterior fossa tumors. The etiopathology of acute cerebellitis remains unknown, although an infectious or postinfectious origin is frequently advocated. Several viral infections maybe associated with cerebellitis in particular varicella virus.

We report a rare case of pseudotumoral cerebellitis secondary to mumps infection which resolved favorably after corticosteroid therapy.

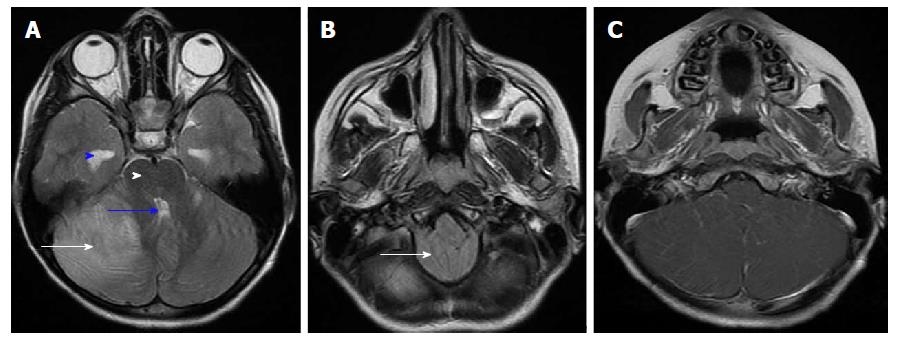

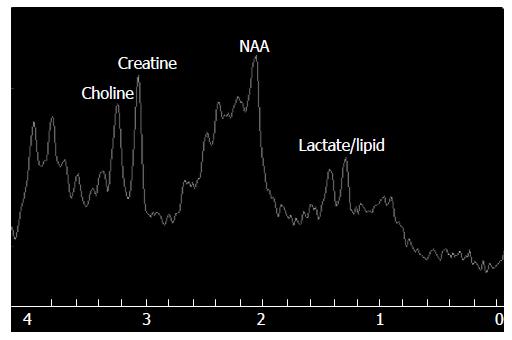

A 6-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with a 2-d history of severe headache, nausea and vomiting. There was no family history of neurological disorders and her psychomotor development was normal. She had a history of a recent episode of mumps infection 10 d before presentation, with spontaneous resolution. Upon admission, the patient had an altered consciousness level and was mildly confused (Glasgow Coma Scale = E4 V4 M6). Neurological examination revealed trunk and gait ataxia with bilateral dysmetria on finger-nose tests. The body temperature was 37.5 °C. Vital signs were initially stable with normal heart and breath rates. Few hours after her admission, she had dysautonomic troubles; her heart rate decreased unexpectedly to 55 beats/min and her arterial pressure dropped to 80/50 mmHg. Therefore, the patient was transferred to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit for close observation. Brain computed tomography scan showed a cerebellar ill-defined hypodense lesion with mass effect on the fourth ventricle and dilation of the upper ventricular system. A multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in order to differentiate between posterior fossa tumor and acute cerebellitis. Brain MRI showed cerebellar high-intensity areas on T2-weighted and FLAIR images predominant on the right side, related to a diffuse edema with mass effect on the fourth ventricle and brainstem, tonsillar herniation and supratentorial hydrocephalus (Figure 1A and B). No bleeding on T2* sequence or diffusion restriction was noted. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequence revealed leptomeningeal enhancement along the cerebellar folia (Figure 1C). Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (TE = 35 ms) showed mildly reduced level of N acetyl aspartate (NAA)/Creatine and normal Choline/Creatine ratios. Doublet of lactate-lipid peak (1.3 ppm) was also found (Figure 2). Biological investigation revealed an hemoglobin concentration of 12.7 g/dL, a white blood cell count of 14280/mm3 (with 85% neutrophils, 9% lymphocytes and 4.8% monocytes), platelet count of. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate showed moderate increase and was 20 mm/h. C-reactive protein level was above 2 mg/L. Lumbar puncture was not performed because of the risk of cerebellar herniation. Serological tests for Epstein Barr virus, human herpes virus, human immunodeficiency virus, rubella virus, parvovirus B19, measles virus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in serum were all negative except for the serological test for mumps virus which was positive with IgM and IgG and positive with IgG in the control serology done 10 d later. Post-infectious acute hemicerebellitis was diagnosed on the basis of the MRI features, the clinical symptoms and the biological findings. The patient was treated with mannitol and corticosteroid. She received IVmethylprednisolone 30 mg/kg per day for 3 d followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg per day tapered within 1 mo. The evolution was rapidly favorable. Eighteen days after discharge, a brain MRI showed a partial resolution of signal alterations in the cerebellar hemispheres. Complete resolution was confirmed by brain MRI performed 3 mo later.

Acute cerebellitis often occurs as a primary infectious, post-infectious, post-vaccination disorder and it may follow a vaccine or drug administration[1]. It is associated with viral or bacterial infections in approximately 24% of the children[4]. Several infectious agents associated with cerebellitis were reported in literature: Varicella-Zoster virus, human herpes virus, Epstein-Barr virus, rubella, pertussis, diphtheria, coxsackie virus, Coxiella burnetti or Mycoplasma pneumoniae[5]. Mumps virus infection causes usually benign diseases and 30% of pediatric cases are asymptomatic[6]. It induces viremia resulting in dissemination of virus to several organ systems, including the central nervous system[7]. Mumps viruses are highly neurotropic, with evidence of central nervous system infection in more than half of all cases of infection[8]. The most common neurological complication of mumps is aseptic meningitis. Severe complications, though rare, include hearing loss in children (5/100000) and encephalitis (incidence of < 2/100000 cases, of which 1% are fatal)[6]. Our patient had an acute cerebellitis post mumps virus infection which is an unusual clinical feature. These severe complications could be explained by the neurovirulence of some mumps virus strains rather than others. This observation has been also shown by Sauder et al[7] through the use of different live attenuated mumps viruses strains. Our observation is distinctive by its clinical and radiological presentations and by its uncommon infective etiology. It illustrates pseudotumoral feature of acute cerebellitis associated with mumps virus infection. Clinical presentation and radiological features were similar to posterior fossa tumors. The challenge in these cases is to differentiate between posterior fossa tumor and acute cerebellitis. MRI is the study of choice to demonstrate cerebellar pathology, which could be undetected on CT. It confirms acute cerebellitis and leads to a more accurate description of the lesion. Cases of cerebellitis involving only one hemisphere are rare and are more difficult to differentiate from tumors. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy is a valuable tool to exclude tumor by showing normal choline/creatine ratio. Most forms of acute cerebellitis have a good clinical outcome and have no need for specific treatment as they are benign forms. However, some cases, like in our report, could be fulminant and should be treated urgently. These severe forms require to start methylprednisolone bolus with a very close observation of clinical and imaging variables.

We report a child with acute cerebellitis secondary to post-mumps infection. This case illustrates that although mumps infection is a benign infection, it could be associated to a severe and atypical cerebellitis syndrome. Imaging techniques especially multimodal MRI represent an interesting tool to differentiate between posterior fossa tumors and acute cerebellitis. The risk of brainstem compression may be life-threatening and indicate an urgent need for treatment.

A 6-year-old girl presented to the emergency department with a 2-d history of severe headache, nausea and vomiting. She had a history of a recent episode of mumps infection 10 d before presentation, with spontaneous resolution.

Acute cerebellitis.

A multimodal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed in order to differentiate between posterior fossa tumor and acute cerebellitis.

Serological tests for Epstein-Barr virus, human herpes virus, human immunodeficiency virus, rubella virus, parvovirus B19, measles virus and Mycoplasma pneumoniae in serum were all negative except for the serological test for mumps virus which was positive with IgM and IgG and positive with IgG in the control serology done 10 d later.

Brain MRI showed cerebellar high-intensity areas on T2-weighted and FLAIR images predominant on the right side, related to a diffuse edema with mass effect on the fourth ventricle and brainstem, tonsillar herniation and supratentorial hydrocephalus. Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted sequence revealed leptomeningeal enhancement along the cerebellar folia. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (TE = 35 ms) showed mildly reduced level of N acetyl aspartate (NAA)/Creatine and normal Choline/Creatine ratios. Doublet of lactate-lipid peak (1.3 ppm) was also found.

Final diagnosis: Post-infectious acute hemicerebellitis.

The patient was treated with mannitol and corticosteroid. She received IV methylprednisolone 30 mg/kg per day for 3 d followed by oral prednisone 1 mg/kg per day tapered within 1 mo.

Pseudotumoral cerebellitis in childhood is an uncommon presentation of cerebellitis mimicking a brain tumor. Imaging techniques especially multimodal MRI represent an interesting tool to differentiate between posterior fossa tumors and acute cerebellitis. The authors describe a case of pseudotumoral cerebellitis in a 6-year-old girl consequent to mumps infection and review the literature on this rare association.

Acute cerebellitis often occurs as a primary infectious, post-infectious, post-vaccination disorder and it may follow a vaccine or drug administration. It is associated with viral or bacterial infections in approximately 24% of the children.

The authors report a child with acute cerebellitis secondary to post-mumps infection. This case illustrates that although mumps infection is a benign infection, it could be associated to a severe and atypical cerebellitis syndrome. Imaging techniques especially multimodal MRI represent an interesting tool to differentiate between posterior fossa tumors and acute cerebellitis. The risk of brainstem compression may be life-threatening and indicate an urgent need for treatment.

The case report is described very well and will be useful to share with the scientific community.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Tunisia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Krishnan T, Shinjoh M, Tlili-Graiess K, Zuccotti G S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang S

| 1. | Morais RB, Sousa I, Leiria MJ, Marques C, Ferreira JC, Cabral P. Pseudotumoral acute hemicerebellitis in a child. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2013;17:204-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Luijnenburg SE, Hanlo PW, Han KS, Kors WA, Witkamp TD, Verbeke JI. Postoperative hemicerebellar inflammation mimicking recurrent tumor after resection of a medulloblastoma. Case report. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2008;1:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | de Ribaupierre S, Meagher-Villemure K, Villemure JG, Cotting J, Jeannet PY, Porchet F, Roulet E, Bloch J. The role of posterior fossa decompression in acute cerebellitis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2005;21:970-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Carceller Lechón F, Duat Rodríguez A, Sirvent Cerdá SI, Khabra K, de Prada I, García-Peñas JJ, Madero López L. Hemicerebellitis: Report of three paediatric cases and review of the literature. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18:273-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Adachi M, Kawanami T, Ohshima H, Hosoya T. Cerebellar atrophy attributed to cerebellitis in two patients. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2005;4:103-107. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: 1] |

| 6. | Gabutti G, Guido M, Rota MC, De Donno A, Ciofi Degli Atti ML, Crovari P; Seroepidemiology Group. The epidemiology of mumps in Italy. Vaccine. 2008;26:2906-2911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sauder CJ, Vandenburgh KM, Iskow RC, Malik T, Carbone KM, Rubin SA. Changes in mumps virus neurovirulence phenotype associated with quasispecies heterogeneity. Virology. 2006;350:48-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Brown JW, Kirkland HB, Hein GE. Central nervous system involvement during mumps. Am J Med Sci. 1948;215:434-441. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: 1] |