Published online Jul 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i7.280

Peer-review started: March 16, 2017

First decision: May 22, 2017

Revised: May 26, 2017

Accepted: June 19, 2017

Article in press: June 20, 2017

Published online: July 16, 2017

Processing time: 119 Days and 18.7 Hours

To investigate the feasibility of initial endoscopic common bile duct (CBD) stone removal in patients with acute cholangitis (AC).

A single-center, retrospective study was conducted between April 2013 and December 2014 and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee at our institution. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to the procedure. The cohort comprised 31 AC patients with CBD stones who underwent endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) for naïve papilla within 48 h after AC onset. We retrospectively divided the participants into two groups: 19 patients with initial endoscopic CBD stone removal (initial group) and 12 patients with delayed endoscopic CBD stone removal (delayed group). We evaluated the feasibility of initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC.

We observed no significant differences between the groups regarding patient characteristics. According to the assessments based on the Tokyo Guidelines, the AC severity of patients with initial endoscopic CBD stone removal was mild to moderate. The use of antithrombotic agents before EBD was less frequent in the initial group than in the delayed group (11% vs 58%, respectively; P = 0.004). All the patients underwent successful endoscopic CBD stone removal and adverse events did not differ significantly between the groups. The number of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography procedures was significantly lower in the initial group than in the delayed group [median (interquartile range) 1 (1-1) vs 2 (2-2), respectively; P < 0.001]. The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial group than for the delayed group [10 (9-15) vs 17 (14-20), respectively; P = 0.010].

Initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC may be feasible when AC severity and the use of antithrombotic agents are carefully considered.

Core tip: Initial endoscopic common bile duct stone removal in patients with acute cholangitis (AC) may be feasible when AC severity and the use of antithrombotic agents are carefully considered.

- Citation: Yamamiya A, Kitamura K, Ishii Y, Mitsui Y, Nomoto T, Yoshida H. Feasibility of initial endoscopic common bile duct stone removal in patients with acute cholangitis. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(7): 280-285

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i7/280.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i7.280

Acute cholangitis (AC) is an acute inflammatory condition caused by a rise in bile duct pressure and biliary infection secondary to biliary obstruction[1]. Clinical findings include fever, abdominal pain and jaundice (Charcot’s triad). Patients with severe AC present with septic shock and altered consciousness in addition to the classical signs of Charcot’s triad (Reynolds’ pentad).

First published in 2007, the Tokyo Guidelines for the management of AC (TG07)[2] were modified in 2013 to the updated version (TG13)[1]. The basic treatment for AC is conservative medical therapy with antimicrobial agents and biliary tract drainage.

According to the TG07, an additional endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) is not necessary during initial biliary drainage. However, in the TG13, based on the clinical condition of the patient, initial common bile duct (CBD) stone removal with an additional EST may be performed. Furthermore, no consensus exists for when CBD stones should be removed in patients with AC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the feasibility of initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC.

This retrospective study was conducted at Showa University Hospital and was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of our institution. The study was registered at the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry (registry number: 000020770). Informed written consent was obtained from each patient prior to the procedure.

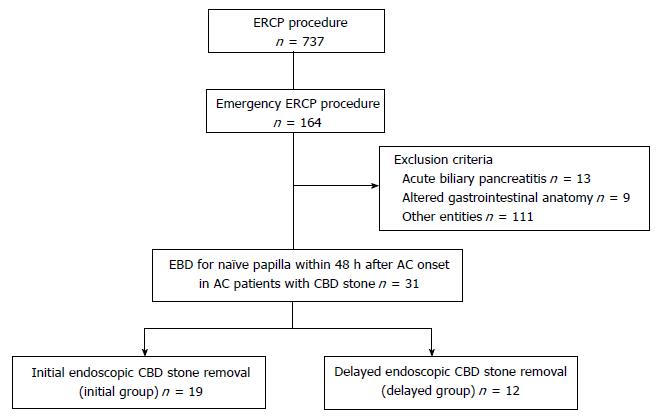

Seven hundred thirty-seven patients underwent an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)-related procedure at our institution between April 2013 and December 2014. Among them, 164 patients underwent an emergency ERCP procedure. Following the exclusion of acute biliary pancreatitis (n = 13), altered gastrointestinal anatomy (n = 9), and other entities (n = 111), we analyzed the remaining 31 AC patients with CBD stones who underwent endoscopic biliary drainage (EBD) for naïve papilla within 48 h after AC onset.

We retrospectively divided the participants into two groups: 19 patients who underwent initial endoscopic CBD stone removal (initial group) and 12 patients who underwent delayed endoscopic CBD stone removal (delayed group) (Figure 1).

The delayed group was defined as patients who received EBD without CBD stone removal at first ERCP and underwent endoscopic CBD stone removal later.

ERCP was performed using a duodenoscope (JF-260V; Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The following devices were employed during the procedure: A sphincterotome with a tip length of 7 mm and a cutting wire length of 20 mm (Autotome RX44; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States), a 0.035-inch guidewire (Jagwire; Boston Scientific), a balloon catheter for CBD stone removal (Multi-3V Plus; Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan), a biliary dilation balloon catheter designed to produce three distinct diameters at three separate pressures (CRETM wire-guided biliary dilation balloon catheter; Boston Scientific), and a 5-Fr pigtail nasobiliary catheter (Create Medic Co. LTD., Tokyo, Japan) or a 7-Fr 10-cm Double Pigtail Stent delivery system Through Pass (Gadelius Medical K.K., Tokyo, Japan) as a drainage catheter and stent.

All ERCP procedures were performed by expert endoscopists. All patients provided written consent to undergo ERCP and were informed of the risks and benefits of the procedure. The patients who exhibited no evidence of altered consciousness or septic shock received ERCP under sedation with benzodiazepines or pentazocine as analgesics. Wire-guided cannulation for selective bile duct cannulation and EST with a small or medium-sized incision of the papilla of Vater were primarily performed to remove the CBD stone. An Erbotom ICC200 (ERBE Elektromedizin GmbH, Tubingen, Germany) was used for the EST using the Endocut mode. The effect 3 current was set at an output limit of 120 W and the forced coagulation current was set at an output limit of 30 W. Patients with large CBD stones (i.e., diameter of 13 mm or more) received endoscopic papillary large balloon dilation (EPLBD) with EST. A balloon catheter was used to remove the CBD stone. All patients received intravenous infusions of a protease inhibitor (gabexate mesilate - 600 mg or nafamostat mesilate - 60 mg) for approximately 12 h (beginning immediately after the ERCP procedures). All patients were administered antibiotics before the ERCP procedure, and antimicrobial therapy was continued until the cholangitis symptoms improved. The off-period for antithrombotic agents was based on the Japanese guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment[3]. Based on the judgment of the endoscopist, either a 5-Fr drainage catheter or a 7-Fr 10-cm double pigtail stent was inserted for EBD.

The primary outcome of this study was the success rate of initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC. The secondary outcomes were the number of ERCP procedures, the incidence of adverse events, the duration of antibiotic administration, the length of hospital stay and hospital costs.

Post-ERCP pancreatitis was defined as the presence of abdominal pain lasting for more than 24 h after ERCP with serum amylase levels 3 times the upper limit of normal or higher and graded by CT when necessary[4]. Bleeding complications were classified as follows: Mild, with hemoglobin drop < 3 g without a need for transfusion; moderate, with transfusion (4 units or less) with no angiographic intervention or surgery; and severe, with transfusion (5 units or more) or additional intervention[4].

Continuous variables are expressed as the median with interquartile range (IQR). Statistical analyses were performed using JMP version 12 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States). Data were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U and χ2 tests. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Patient characteristics are presented in Table 1. No significant differences between the groups were observed regarding age, sex, AC severity, CBD diameter, number of CBD stones, diameter of CBD stones, periampullary diverticulum, period until EBD, blood CRP level before EBD or positive blood cultures. The use of antithrombotic agents before EBD was less frequent in the initial group than in the delayed group (11% vs 58%, respectively; P = 0.004).

| Initial group (n = 19) | Delayed group (n = 12) | P value | |

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 71 (62-80) | 80 (74-84) | 0.0641 |

| Sex, male/female, n | 11/8 | 6/6 | 0.6672 |

| AC severity3, mild/moderate/severe, n | 11/8/0 | 5/4/3 | 0.0722 |

| CBD diameter, median (IQR), mm | 9 (8-10) | 11 (8-13) | 0.1691 |

| Number of CBD stones, single/multiple, n | 9/10 | 6/6 | 0.8862 |

| Diameter of CBD stone, < 10 mm/≥ 10 mm, n | 15/4 | 9/3 | 0.7982 |

| Periampullary diverticulum | 9 (47) | 4 (33) | 0.4412 |

| Use of antithrombotic agents before EBD | 2 (11) | 7 (58) | 0.0042 |

| Period until EBD from AC onset, < 24 h/24-48 h, n | 11/8 | 8/4 | 0.6482 |

| Blood CRP level before EBD, median (IQR), mg/dL | 3.9 (1.4-6.7) | 5 (1.6-12.2) | 0.4291 |

| Positive blood culture, n/total | 6/14 (43) | 5/7 (71) | 0.2172 |

There was no significant difference between the groups regarding procedures involving the ampulla, such as EST or EPLBD, to remove CBD stones. All patients underwent successful endoscopic CBD stone removal using a balloon catheter (Table 2).

| Initial group (n = 19) | Delayed group (n = 12) | P value | |

| Procedures for ampulla, EST/EPLBD with EST, n | 18/1 | 10/2 | 0.2961 |

| Use of balloon catheter for stone removal | 19 (100) | 12 (100) | |

| Successful CBD stone removal | 19 (100) | 12 (100) | |

| Number of ERCP procedures, median (IQR) | 1 (1-1) | 2 (2-2) | < 0.0012 |

| Adverse events, pancreatitis/bleeding/perforation, n | 0/0/0 | 0/1/0 | 0.2011 |

| Duration of antibiotic administration, median (IQR), d | 7 (5-8) | 6 (5-7) | 0.0592 |

| Hospital stay, median (IQR), d | 10 (9-15) | 17 (14-20) | 0.0102 |

| Hospital costs, median (IQR), $ | 726 (579-1028) | 988 (868-1033) | 0.2242 |

The number of the ERCP procedures performed was significantly lower in the initial group than in the delayed group [1 (1-1) vs 2 (2-2) for the initial and delayed groups, respectively; P < 0.001] (Table 2).

Adverse events did not differ significantly between the two groups. Post-ERCP pancreatitis or perforation did not occur in either group. Mild bleeding 4 d after ERCP occurred in 1 patient in the delayed group (Table 2).

The duration of antibiotic administration did not differ significantly between the groups [7 (5-8) d vs 6 (5-7) d for the initial and delayed groups, respectively, P = 0.059] (Table 2).

The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial group than that for the delayed group [10 (9-15) d vs 17 (14-20) d for the initial and delayed groups, respectively; P = 0.010] (Table 2).

There was no significant difference in hospital cost between the groups [$726 (579-1028) vs $988 (868-1033) for the initial and delayed groups, respectively, P = 0.224] (Table 2).

This study suggested that emergency initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC may be feasible when AC severity and the use of antithrombotic agents are carefully considered.

In 2013, the TG07 was modified to the updated version, TG13[1]. AC results from causes such as CBD stones, benign biliary tract strictures, biliary anastomotic strictures and malignant biliary tract strictures. Though a CBD stone is the most frequent etiology of AC, the incidences of AC due to malignant biliary tract stricture and sclerosing cholangitis have been increasing recently[5,6].

The major changes reflected in the TG13 were a rearrangement of the diagnostic items and the exclusion of abdominal pain from the diagnostic list. Cholangitis severity was categorized as grade I (mild), grade II (moderate) and grade III (severe). Kiriyama et al[7] investigated the accuracy of the TG13. The sensitivity for AC severity is 91.8%, and the specificity for AC is 77.7%.

According to the TG13, appropriate treatment during the acute phase of AC is important because the mortality associated with AC is 2.7%-10%. Among 60842 AC cases extracted from the Japanese administrative database according to the Diagnosis Procedure Combination system of Japan, the mortality was 2.7%[8]. The primary cause of death among patients with AC is multiple organ failure associated with irreversible shock[9].

The TG13 further recommends treatment based on AC severity. The initial treatment, which includes a full dose of antimicrobial agents, is provided for all patients with AC. For non-responders with mild and moderate AC, biliary drainage should be performed immediately. For patients with severe AC, appropriate organ support is required, and biliary drainage should be performed after hemodynamic stabilization has been achieved[10]. Biliary drainage includes percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage, surgical biliary drainage, EBD and endoscopic ultrasonography-guided biliary drainage. EBD is recommended as the first choice because it is considered a minimally invasive biliary drainage technique[11-13].

There are several differences in EST between the TG07 and TG13. In the TG07, an additional EST is not necessary because EST is associated with serious complications, such as hemorrhage. AC alone is a risk factor for post-EST hemorrhage[14]. In particular, EST should be avoided in patients with severe AC because they often have blood-coagulation disorders. According to the TG13, EST may be indicated for the initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC[1]. These recommendations suggest that the choice of performing an additional EST should be based on the patient’s clinical condition[15].

Recently, studies evaluating initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC have emerged in the literature. Eto et al[16] reported that the improvement rate of cholangitis was 90% and that the rate of complications was 10% (post-ERCP pancreatitis, hemorrhage, cholecystitis, or pneumonia). Notably, hemorrhage occurred in 2% of patients[16].

At our institution, patients with moderate and severe AC undergo emergency EBD. We also perform emergency EBD in patients with mild AC and high fever (> 38 °C) or severe abdominal pain. When AC patients with CBD stones are administered antithrombotic agents, we consider the off-period of these drugs and perform additional EST according to the Japanese guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment[3]. In this guideline, EST is classified in the high bleeding risk group. We have performed additional EST and CBD stone removal in patients with mild and moderate AC. Based on the guideline, we do not perform additional EST for the following patients: Those taking antithrombotic agents that require an off-period of more than 5-7 d; those taking more than 2 types of antithrombotic agents; and those with evidence of septic shock. Therefore, these patients received only EBD. In this study, the use of antithrombotic agents before EBD was less frequent in the initial group than in the delayed group (P = 0.004). Hemorrhage occurred in 1 patient from the delayed group, an older adult with underlying disease who was taking more than 2 types of antithrombotic agents. After the EBD and antithrombotic agent off-period, the patient underwent successful delayed CBD stone removal with EST. However, this patient developed a mild hemorrhage 4 d after the procedure.

In this study, emergency initial endoscopic CBD stone removal was feasible for patients with mild or moderate AC when the guidelines in the TG13 and the recommendations for the use of antithrombotic agents were strictly followed. The number of ERCP procedures was significantly less in the initial group than in the delayed group (P < 0.001) because the delayed group underwent ERCP for CBD stone removal after the severe AC had subsided or during the antithrombotic agent off-period. The length of hospital stay was significantly shorter for the initial group than for the delayed group (P = 0.010) with no significant differences regarding the number of adverse events observed between the two groups. Thus, initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC may reduce the treatment-associated patient burden.

The limitations of this study are the single-center focus, the retrospective design and the small number of patients. Additional multicenter, randomized controlled trials are necessary to confirm the feasibility of emergency initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC.

Emergency initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC may be feasible when AC severity and the use of antithrombotic agents are carefully considered.

Initial endoscopic common bile duct (CBD) stone removal in patients with acute cholangitis (AC) may reduce the number of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures performed and the length of hospital stay. However, there is no consensus on when CBD stones should be removed in patients with AC. The aim of this study was to investigate the feasibility of initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC.

The current standard for treating AC patients with CBD stones is a conservative medical approach with antimicrobial agents and biliary drainage. However, few studies have evaluated the timing of CBD stone removal in patients with AC.

The authors compared the clinical outcomes among patients with AC who underwent either initial endoscopic CBD stone removal or delayed endoscopic CBD stone removal. The number of ERCP procedures and the length of hospital stay were significantly reduced in the initial group compared to that in the delayed group.

Emergency initial endoscopic CBD stone removal in patients with AC may reduce subsequent patient burden associated with the treatment. However, multicenter, randomized, controlled trials are needed to confirm these findings.

Endoscopic CBD stone removal is a stone removal method that utilizes the ERCP-related procedure with a duodenoscope.

Although this is a small study, it was well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript.

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Ooi LLPJ, Rodrigues AT S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gomi H, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Miura F, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ. TG13: Updated Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 206] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Takada T, Kawarada Y, Nimura Y, Yoshida M, Mayumi T, Sekimoto M, Miura F, Wada K, Hirota M, Yamashita Y. Background: Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:1-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fujimoto K, Fujishiro M, Kato M, Higuchi K, Iwakiri R, Sakamoto C, Uchiyama S, Kashiwagi A, Ogawa H, Murakami K. Guidelines for gastroenterological endoscopy in patients undergoing antithrombotic treatment. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cotton PB, Lehman G, Vennes J, Geenen JE, Russell RC, Meyers WC, Liguory C, Nickl N. Endoscopic sphincterotomy complications and their management: an attempt at consensus. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:383-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1890] [Cited by in RCA: 2036] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Lipsett PA, Pitt HA. Acute cholangitis. Surg Clin North Am. 1990;70:1297-1312. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Gigot JF, Leese T, Dereme T, Coutinho J, Castaing D, Bismuth H. Acute cholangitis. Multivariate analysis of risk factors. Ann Surg. 1989;209:435-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kiriyama S, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Mayumi T, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Büchler MW, Yokoe M. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholangitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:548-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Murata A, Matsuda S, Kuwabara K, Fujino Y, Kubo T, Fujimori K, Horiguchi H. Evaluation of compliance with the Tokyo Guidelines for the management of acute cholangitis based on the Japanese administrative database associated with the Diagnosis Procedure Combination system. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:53-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chijiiwa K, Kozaki N, Naito T, Kameoka N, Tanaka M. Treatment of choice for choledocholithiasis in patients with acute obstructive suppurative cholangitis and liver cirrhosis. Am J Surg. 1995;170:356-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gallagher EJ, Esses D, Lee C, Lahn M, Bijur PE. Randomized clinical trial of morphine in acute abdominal pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:150-160, 160.e1-e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lai EC, Mok FP, Tan ES, Lo CM, Fan ST, You KT, Wong J. Endoscopic biliary drainage for severe acute cholangitis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1582-1586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 410] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Boender J, Nix GA, de Ridder MA, Dees J, Schütte HE, van Buuren HR, van Blankenstein M. Endoscopic sphincterotomy and biliary drainage in patients with cholangitis due to common bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:233-238. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Lau JY, Chung SC, Leung JW, Ling TK, Yung MY, Li AK. Endoscopic drainage aborts endotoxaemia in acute cholangitis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:181-184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, Moore JP, Fennerty MB, Ryan ME, Shaw MJ. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1716] [Cited by in RCA: 1689] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Itoi T, Tsuyuguchi T, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Pitt HA, Kim MH, Belli G, Mayumi T, Yoshida M, Miura F. TG13 indications and techniques for biliary drainage in acute cholangitis (with videos). J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Eto K, Kawakami H, Haba S, Yamato H, Okuda T, Yane K, Hayashi T, Ehira N, Onodera M, Matsumoto R. Single-stage endoscopic treatment for mild to moderate acute cholangitis associated with choledocholithiasis: a multicenter, non-randomized, open-label and exploratory clinical trial. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2015;22:825-830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |