Published online Jun 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.222

Peer-review started: December 6, 2016

First decision: January 13, 2017

Revised: February 14, 2017

Accepted: April 23, 2017

Article in press: April 24, 2017

Published online: June 16, 2017

Processing time: 191 Days and 7.8 Hours

Gangliocytic paraganglioma (GP) is a rare tumor of uncertain origin most often located in the second portion of the duodenum. It is composed of three cellular components: Epithelioid endocrine cells, spindle-like/sustentacular cells, and ganglion-like cells. While this tumor most often behaves in a benign manner, cases with metastasis are reported. We describe the case of a 62-year-old male with a periampullary GP with metastases to two regional lymph nodes who was successfully treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy. Using PubMed, EMBASE, EBSCOhost MEDLINE and CINAHL, and Google Scholar, we searched the literature for cases of GP with regional lymph node metastasis and evaluated the varying presentations, diagnostic workup, and disease management of identified cases. Thirty-one cases of GP with metastasis were compiled (30 with at least lymph node metastases and one with only distant metastasis to bone), with age at diagnosis ranging from 16 to 74 years. Ratio of males to females was 19:12. The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (55%) and gastrointestinal bleeding or sequelae (42%). Twenty-five patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Five patients were treated with local resection alone. One patient died secondary to metastatic disease, and one died secondary to perioperative decompensation. The remainder did well, with no evidence of disease at follow-up from the most recent procedure (except two in which residual disease was deliberately left behind). Of the 26 cases with sufficient histological description, 16 described a primary tumor that infiltrated deep to the submucosa, and 3 described lymphovascular invasion. Of the specific immunohistochemistry staining patterns studied, synaptophysin (SYN) stained all epithelioid endocrine cells (18/18). Neuron specific enolase (NSE) and SYN stained most ganglion-like cells (7/8 and 13/18 respectively), and S-100 stained all spindle-like/sustentacular cells (21/21). Our literature review of published cases of GP with lymph node metastasis underscores the excellent prognosis of GP regardless of specific treatment modality. We question the necessity of aggressive surgical intervention in select patients, and argue that local resection of the mass and metastasis may be adequate. We also emphasize the importance of pre-surgical assessment with imaging studies, as well as post-surgical follow-up surveillance for disease recurrence.

Core tip: Duodenal gangliocytic paragangliomas (GP) generally behave in a benign manner, but infrequently lymph node, and rarely distant, metastases occur. Even in such cases, prognosis remains excellent with only a single reported disease-related death. Here we report a patient with a duodenal GP with regional lymph node metastases and review the literature to help direct management of the rare tumor. In reviewing the literature, achieving complete resection of primary tumor and positive lymph nodes appears to be curative. As such, this should be the therapeutic goal in surgically fit patients.

- Citation: Cathcart SJ, Sasson AR, Kozel JA, Oliveto JM, Ly QP. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastases: A case report and comparative review of 31 cases. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(6): 222-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i6/222.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i6.222

Gangliocytic paraganglioma (GP) is a rare tumor most often located in the ampullary/periampullary region of the duodenum. It is composed of three cell types: Epithelioid endocrine cells, spindle-like/sustentacular cells, and ganglion-like cells. Patients frequently present with symptoms related to gastrointestinal bleeding; however, the diagnosis is occasionally made incidentally[1,2]. While this tumor typically behaves in a benign manner, there have been rare cases with metastasis, most often to regional lymph nodes. We report a case of periampullary duodenal GP with metastases to regional lymph nodes treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy. We also review published literature on other GPs demonstrating metastasis with the intention to help define the appropriate diagnostic work-up and management of this rare entity.

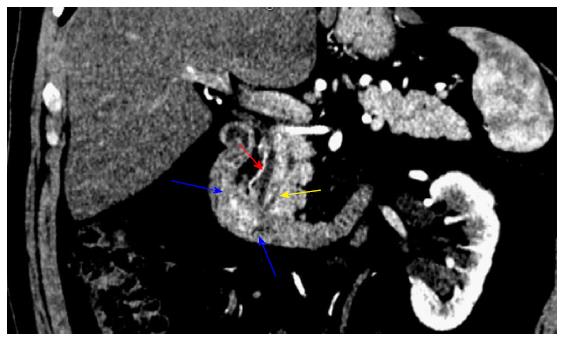

Our patient was a 62-year-old male with a periampullary duodenal mass discovered incidentally during a surveillance esophagogastroduodenoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus. An endoscopic biopsy showed only duodenal mucosa with changes suggestive of peptic duodenitis. Subsequent endoscopic ultrasound revealed a 1.5 cm × 0.8 cm mass with a 1.2 cm × 0.8 cm periduodenal lymph node. A fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy and endoscopic tunneled biopsy of the duodenal mass was performed, which collectively showed features consistent with a neuroendocrine tumor. Computed tomography (CT) imaging demonstrated a well-circumscribed intraluminal duodenal mass (2.1 cm × 1.4 cm) with mild enhancement and no discernable pathologic lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). Retrospective review of CT imaging from two years prior did not show an obvious mass. The patient was asymptomatic. His past medical history was significant for Barrett’s esophagus, as mentioned above, as well as hypertension, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, and hyperlipidemia. He had no smoking history and only light alcohol usage.

Two and a half months later, the patient underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy, hepatic artery lymph node and portal lymph node excision, cholecystectomy, and partial gastrectomy (the pylorus appeared ischemic intra-operatively). The patient’s course was complicated by a pancreatic leak and a pulmonary embolism. CT imaging performed at 19 mo showed no evidence of disease recurrence, and a routine healthcare check at 30 mo revealed no clinical evidence of disease recurrence.

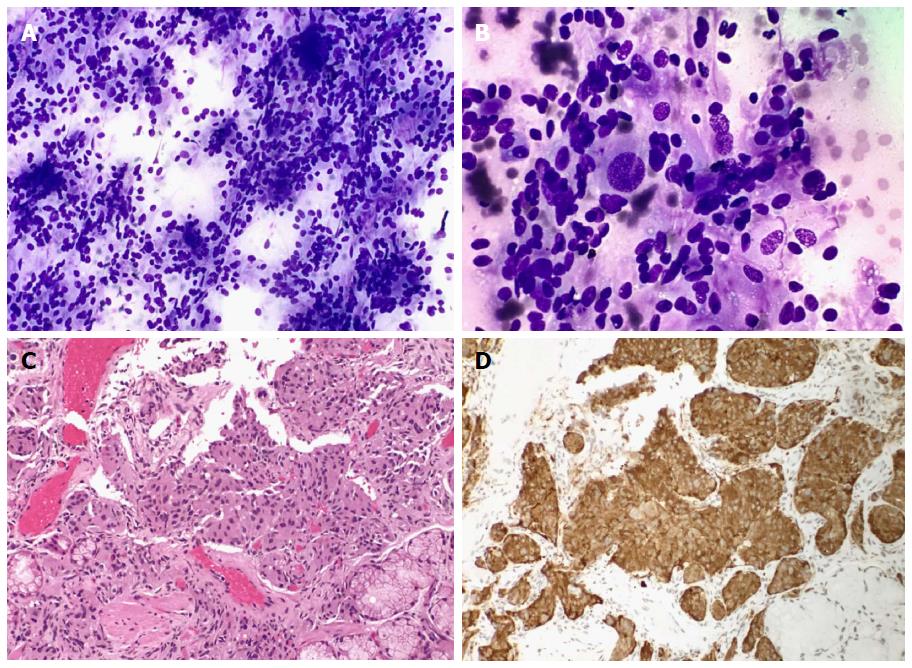

Cytological smear preparation (Diff-Quick and Papanicolaou stains) from the duodenal mass FNA demonstrated a cellular specimen composed of intermediate-sized, bland epithelioid cells with round to oval nuclei. Rare large ganglioid cells with eccentric nuclei and a prominent nucleolus were seen. A concurrent endoscopic tunneled biopsy contained three fragments of duodenal mucosa, one of which had a few nests of neuroendocrine tumor cells within the submucosa, which stained positively for CAM 5.2 and synaptophysin and negatively for chromogranin (Figure 2).

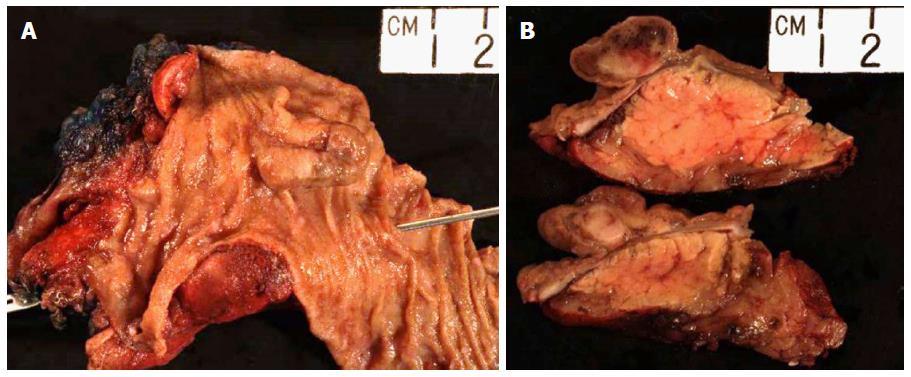

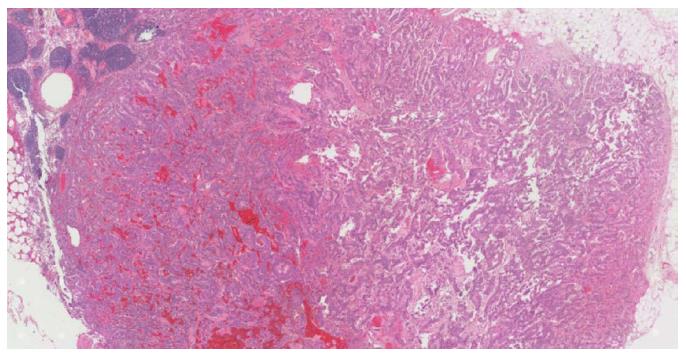

Grossly, the resected surgical specimen included a portion of duodenum with a 2.0 cm × 1.3 cm × 0.7 cm nodule protruding into the lumen. Overlying mucosa was intact. The lesion was 2.0 cm proximal to the ampulla of Vater. On sectioning, the mass was tan-white with focal grey-black discoloration and confined to the submucosa (Figure 3).

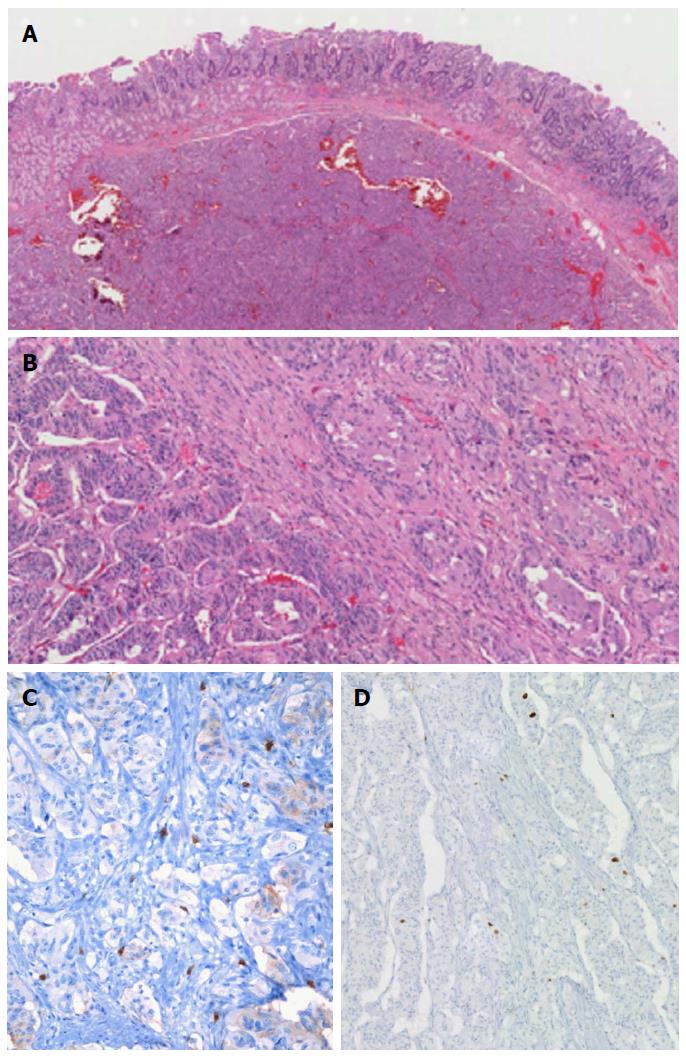

Microscopic examination revealed a submucosal nodule in the duodenum with three distinct cell populations. Epithelioid endocrine cells were arranged in trabeculae and nests interspersed with spindled sustentacular cells. Gangliocytic cells were scattered throughout (Figure 2). The spindle cell population stained positively for S-100, the gangliocytic cells stained positively for calretinin, and the epithelioid cells stained positively for chromogranin and synaptophysin. No mitotic figures were identified. Ki-67 immunohistochemical stain showed a proliferative index of 2% within the tumor cells. Within the primary tumor, CD117 immunohistochemical staining demonstrated up to 15 mast cells per high power field (hpf) focally, with most areas having 1 to 5 per hpf (Figure 4D). Within the lymph node metastasis, up to 7 mast cells per hpf were identified, while most areas had only 1 to 2 per hpf.

There was no intratumoral lymphovascular or perineural invasion identified, nor was there invasion into the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma. The hepatic artery lymph node and portal lymph node were also free of disease. Metastatic tumor was discovered in three of eight periduodenal lymph nodes (Figure 5). Metastases stained similarly to the primary with regard to S-100, chromogranin, and synaptophysin, but stained negatively for calretinin.

Using PubMed, EMBASE, EBSCOhost MEDLINE and CINAHL, and Google Scholar databases, we searched for cases of GP with regional and distant metastases using variations on the key word/phrases “gangliocytic paraganglioma”, “lymph nodes”, “metastasis”, and “distant spread”. We included only cases with at least an abstract written in English or French. Four of the included cases were published as poster presentation abstracts at national and international conferences. Two poster presentation abstracts were not included due to either insufficient patient data or citation information. Finally, we excluded one case which was sited in other literature reviews, as it reported the presence of only two cellular components[3].

Our literature search produced 31 cases of GP with metastatic disease (30 with at least regional lymph node involvement and one with only a single metastasis to the manubrium) (Table 1). In 28 cases, lymph node involvement/metastatic disease was present at the time of initial diagnosis (26 cases with disease spread present in initial surgical resection; 1 case with regional disease diagnosed on follow-up surgery for positive margins[2]; 1 case with regional disease diagnosis on pancreaticoduodenectomy with lymph node dissection performed after a local resection demonstrated tumor with muscularis mucosa invasion and lymphovascular space invasion[4]), while metastatic disease/lymph node involvement was diagnosed on follow-up surveillance in 2 cases[5,6]. Of the 28 cases with initial synchronous metastases/regional disease, 14 reported preoperative imaging that was suspicious for disease spread[7-19], while in 2 cases regional disease was discovered intraoperatively with frozen section confirmation, prompting a pancreaticoduodenectomy[20,21]. In 29 cases, the primary lesion occurred in the duodenum. Fourteen were in the duodenal ampulla, 6 were periampullary, and 8 were in the 2nd portion or the junction between the 2nd and 3rd portions of the duodenum, and 1 was in the 3rd portion of the duodenum. Two primary tumors occurred in the head of the pancreas[6,22]. We included only cases with histological evidence of regional spread/metastatic disease.

| Ref. | Year of publication | Age at diagnosis (yr) | Sex | Presenting symptoms | Primary location | Largest diameter, primary (mm) | Site(s) of metastasis | LNs sampled | LNs positive | Therapy | Follow-up (mo) |

| Büchler et al[7] | 1985 | 50 | M | GI bleeding | D2, ampulla | 30 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 1 | Local resection | 20, NED |

| Korbi et al[24] | 1987 | 73 | F | GI bleeding, weight loss, cardiac decompensation | D2, ampulla | 90 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 1 | PD | 0, died POD 7 |

| Inai et al[4] | 1989 | 17 | M | GI bleeding | D2, ampulla | 20 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 1 | Local resection, followed by PD with LND | 32, NED |

| Hashimoto et al[20] | 1992 | 47 | M | Asymptomatic, incidental | D2, ampulla | 65 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 1 | PD with LND | 14, NED |

| Dookhan et al[5] | 1993 | 41 | M | Abdominal pain, partial duodenal obstruction | D2 | 25 | Mesentery, mesenteric LNs | NR | 2-3 | Local resection (1981); resection D4, proximal jejunum, mesenteric mass (1992) | 131, recurrence and metastasis |

| Takabayashi et al[33] | 1993 | 63 | F | Abdominal pain | D3 | 32 | Regional LN | NR | 1 | PPPD | 24, NED |

| Tomic et al[22] | 1996 | 74 | M | Anemia, steatorrhea, abdominal pain, weight loss | Pancreas, head | 40 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 1 | PD | 19, NED |

| Henry et al[6] | 2003 | 50 | M | Jaundice | Pancreas, head | 30 | Manubrium | NR | 0 | FNA1, followed by PD, followed by manubrium resection | 21, NED |

| Sundararajan et al[1] | 2003 | 67 | F | Asymptomatic, incidental | D2 | 50 | Regional LNs | NR | 2 | PD with LND | 9, NED |

| Wong et al[23] | 2005 | 49 | F | GI bleeding, abdominal pain | D2, periampullary | 14 | Periduodenal and Peripancreatic LNs | 7 | 6 | PPPD with LND, radiotherapy | 12, NED |

| Witkiewicz et al[2] | 2007 | 38 | F | Abdominal pain | D2, periampullary | 15 | Regional LNs | 7 | 2 | Local resection, followed by PPPD | NR |

| Mann et al[8] | 2009 | 17 | F | Duodenal obstruction, weight loss, abdominal pain | D2/D3 junction | Regional LNs | 11 | 4 | PD | 7, NED | |

| Okubo et al[9] | 2010 | 61 | M | GI bleeding, abdominal pain | D2, ampulla | 30 | Regional LNs | NR | 1 | PPPD with LND | 6, NED |

| Saito et al[10] | 2010 | 28 | M | GI bleeding | D2, ampulla | 17 | Regional LNs | N/A | 2 | Local resection, followed by PD | N/A |

| Uchida et al[11] | 2010 | 67 | F | Anemia | D2 | N/A | LN | N/A | N/A | PD | N/A |

| Ogata et al[27] | 2011 | 16 | M | GI bleeding | D2, ampulla | 35 | Peripancreatic LNs | NR | 4 | PPPD with LND | 36, NED |

| Barret et al[12] | 2012 | 51 | F | GI bleeding | D2, ampulla | 25 | Peripancreatic LNs | NR | 2 | FNA, followed by PD | 96, NED |

| Rowsell et al[13] | 2011 | 52 | F | Asymptomatic, incidental | D2, periampullary | 10 | Regional LNs, liver nodule | 23 | 2 | PD, post-op octreotide injections | 27, No change in residual liver metastases |

| Dustin et al[14] | 2011 | 56 | F | Abdominal pain, weight loss | D2, periampullary | 18 | Retroperitoneal LN, later resection Peripancreatic LNs | 10 | 3 | Local resection of retroperitoneal mass, followed by duodenal mass FNA, followed by PPPD with LND and cholecystectomy | NR |

| Fiscaletti et al[25] | 2011 | 61 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | D2, minor papilla (discovered incidentally) | 15 | Peripancreatic LN | 7 | 1 | FNA2, followed by PPPD | 12, NED |

| Amin et al[15] | 2013 | 57 | M | Abdominal pain, vomiting | D2, ampulla | 30 | Portal hepatic LNs, Liver | NR | NR | Resection of duodenal mass, retropancreatic mass, part of hepatic lesion, enlarged portal lymph nodes | 8, Residual liver lesion slowly enlarging |

| Choi et al[21] (poster) | 2014 | 41 | M | GI bleeding | D2 | 25 | Periduodenal LN | 11 | 1 | PD | NR |

| Li et al[16] | 2014 | 47 | M | Abdominal pain | D2, periampullary | 30 | Regional LNs, pelvic cavity, liver | 16 | 7 | PD, radiotherapy, chemotherapy | 13, died secondary to liver and pelvic metastases |

| Micev et al[30] (poster) | 2014 | 57 | M | Abdominal pain, back pain, intermittent jaundice | D2, ampulla | 35 | Regional LNs | NR | 2 | NR | NR |

| Shi et al[17] | 2014 | 47 | M | Abdominal pain, weight loss | D2, ampulla | 40 | Regional LNs | 20 | 8 | PD with LND | 24, NED |

| Dowden et al[32] | 2015 | 59 | F | Abdominal pain, weight loss | D2, ampulla | 28 | Regional LNs | 22 | 2 | FNA, followed by PPPD | 5, NED |

| Lei et al[19] | 2015 | 45 | M | GI bleeding, weight loss, vomiting and diarrhea, abdominal cramps (functional tumor) | D2 | 15 | Periduodenal LN | NR | 1 | FNA, followed by ampullectomy with periduodenal and retropancreatic LND | 3, functional symptoms and CT showing lymphadenopathy, lost to follow-up |

| Sun et al[26] (poster) | 2015 | 40 | F | Abdominal pain | D2, ampulla | 20 | Peripancreatic LN | NR | 13 | FNA, followed by PD | 12, NED |

| Wang et al[18] | 2015 | 49 | M | Abdominal pain | D2 | 33 | Regional LNs | 9 | 3 | PD with LND, chemotherapy | 36, NED |

| Hu et al[31] | 2016 | 65 | M | GI bleeding | D2 | 30 | LN | NR | 1 | Local resection | 2, NED |

| Current case | 2016 | 62 | M | Asymptomatic, incidental | D2, periampullary | 20 | Regional LNs | 8 | 3 | FNA, PD | 30, NED |

Clinical findings: Among the 31 patients studied, age at presentation ranged from 16-74 years, with 77% (24/31) presenting in the 5th-7th decade of life. There was a male predominance, with a male to female ratio of 19:12. The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal pain (55%) and gastrointestinal bleeding or the resultant symptomatic anemia (42%). Eight patients presented with weight loss as one of their symptoms (26%). One patient with a pancreatic primary presented with steatorrhea[22], while the other presented with jaundice[6].

Management: Twenty-five of the 31 patients with regional spread/metastatic disease underwent a pancreaticoduodenectomy, 4 of which occurred following local resection. In one case, massive hematemesis prompted an exploratory laparotomy and local resection of tumor, which was found to have muscularis mucosa invasion and lymphovascular space invasion[4]. In another case, pancreaticoduodenectomy was performed after local resection demonstrated positive margins[2]. In the third case, pancreaticoduodenectomy followed resection of an 11 cm multiloculated retroperitoneal mass, which was determined to be a lymph node containing metastatic PG. Further workup revealed a 2 cm periampullary submucosal mass in the duodenum[14]. In the fourth case, regional lymph node involvement was found in the initial local resection, as well as in the secondary resection[10].

Four of the 31 patients were treated with local resection only, one of which underwent initial local resection of the primary tumor and lymph node metastasis with no signs of recurrence over a 20-mo follow-up period[7]. The second patient presented with gastrointestinal complaints and was found to have a partially calcified mass in the liver and abdomen, which was initially diagnosed as metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. Later testing revealed a duodenal lesion extending posteriorly to the pancreas with lymph node and liver involvement. Subsequently, the patient underwent resection of the duodenal lesion, retropancreatic mass, part of the hepatic lesions, and all enlarged portal lymph nodes. CT at 8 mo follow-up revealed a slowly enlarging residual liver lesion[15].

One remarkable patient with innumerable liver metastases in addition to her lymph node metastases was treated with adjuvant octreotide injections for residual disease left behind in her liver. At 27 mo follow-up, she had no significant change in residual disease[13]. One patient with metastases to 6 of 7 sampled lymph nodes received adjuvant external beam radiotherapy and was disease-free at 12 mo[23], while another patient with metastases in 3 of 9 sampled lymph nodes received 5 cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy (regimen not specified) with no evidence of disease at 36 mo[18]. Finally, one patient expired secondary to metastatic disease burden. On initial pancreaticoduodenectomy, the patient was diagnosed with a periampullary GP metastatic to 7 of 16 regional lymph nodes. A follow-up CT at 4 mo revealed liver and pelvic cavity metastases, and radiotherapy (total dose of 5040 cGy) was performed with no improvement, followed by chemotherapy (combination of cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and dacarbazine) with no improvement. Nine months after the initial surgery, he underwent partial resection of the pelvic mass. His liver mass continued to enlarge, and he developed persistent ascites and fever and passed away 13 mo following his initial operation[16]. This is the only case, to our knowledge, to follow a lethal course directly resultant from disease burden.

Follow-up: Of the 25 cases with available follow-up (including the case presented here), follow-up ranged from 0 (perioperative demise) to 131 mo after the initial surgical intervention. In most cases, patients remained without evidence of recurrent disease. Exceptions include the two with residual liver disease and the one with death secondary to metastatic disease as detailed above, as well as a patient whose 3-mo follow-up revealed a return of functional symptoms (elevated serum chromogranin A and serotonin at the time of initial diagnosis) and a CT demonstrating lymphadenopathy. This last patient was unfortunately lost to follow-up[19]. In one case, the patient died from anuria and cardiorespiratory decompensation one week after initial surgery[24]. The minority of case reports that discussed methods of surveillance described using CT scans, endoscopy, and physical examination.

Histopathological findings: Pathologic findings are briefly summarized in Table 2. All cases included describe three cellular components in the primary tumor: Epithelioid/endocrine-like, spindle-like, and ganglion-like. Of those, immunohistochemical staining of each cell type was described for 19[1,2,4-7,9,12-20,22,24-26]. Bucher et al[3] describe a case of an ampullary “alveolar paraganglioma” with lymph node metastases, which has been included in other GP literature reviews. We have elected to omit this case from our comparative review, maintaining strict inclusion of only cases with the three separate components described[3]. Twenty-one cases described histology of the metastatic disease, of which 15 reported all three components to be present.

| General | Rare tumor of uncertain origin and low malignant potential, composed of epithelioid cells, spindle cells, and ganglion-like cells |

| Clinical features | Most often 5th-7th decade of life |

| Most often abdominal pain or gastrointestinal bleeding | |

| Gross findings | 90% occurring in second portion of duodenum |

| 10-90 cm in greatest dimension (average 30 cm) | |

| Cytologic findings | Typically cellular specimen |

| Epithelioid cells predominate | |

| All three components may be present | |

| Histologic findings | Epithelioid cells, spindle-like/sustentactular cells, and ganglion-like cells |

| Submucosal | |

| Unencapsulated | |

| Necrosis absent | |

| No to rare mitoses | |

| Frequent extension beyond submucosa and/or lymphovascular invasion | |

| Metastases: 75% of those reported demonstrated all three cellular components; 25% predominantly epithelioid |

Most frequently, mitotic figures were not found among tumor cells. When present, they consisted of no more than two per ten hpf. Necrosis was absent from the primary tumor site in all cases that included a histologic description. No cases were described as having a tumor capsule. Seventeen cases specified extent of primary tumor invasion and/or the presence of lymphovascular space invasion. Thirteen described invasion into at least the muscularis propria, and one invaded into the pancreas[17]. Three cases reported lymphovascular space invasion[4,20,27].

Of the cases describing immunohistochemical staining, those most commonly employed were S-100, chromogranin (CG), synaptophysin (SYN), somatostatin (SS), cytokeratin (CK), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), neurofilament (NF), and pancreatic polypeptide (PP). Nineteen cases described specific staining patterns among the three cell populations. Of note, SYN stained all epithelioid endocrine cells studied (18/18), NSE and SYN stained most ganglion-like cells studied (7/8 and 12/18 respectively), and S-100 stained all spindle-like/sustentacular cells studied (21/21).

While most GPs are restricted to the duodenal submucosa, a small but significant proportion demonstrates regional spread/metastasis, thus defining the malignant potential of this lesion. The rarity of this tumor has made it difficult to determine a standard of care and thus optimum treatment parameters are undefined. Until recently, no reported deaths had been directly related to underlying disease process. While one patient experienced tumor progression refractory to adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy with subsequent death, the overwhelming trend is that of low malignant potential and indolent behavior, despite nodal metastasis. Even with distant metastatic disease, patients seem to generally have a good prognosis. Our aim was to help further characterize the behavior of this rare tumor to help guide diagnosis and management.

In 2011, Okubo et al[28] reported a rate of lymph node metastasis at 6.9% (12/173 cases). In their survey, they also reported no significant difference in gender among patients with and without lymph node metastasis. They did, however, find a significant difference for the rate of lymph node metastasis among patients with GP extending beyond the submucosal layer versus those with GP confined to the submucosa[28]. Though our study population is small and does not include cases without metastasis, our findings appear to be consistent. Of those that reported depth of invasion, primary tumor invaded into the muscularis propria and/or demonstrated lymphovascular invasion in 86% (18/21) of cases. Okubo et al[28] showed a rate of 92% (11/12) of cases with lymph node metastasis when the primary tumor invaded beyond the submucosal layer. As mentioned above, they further clarified that there was a significant difference among those that did not exhibit metastasis. They concluded that tumor penetrating through the submucosal layer may be a risk factor for disease progression[28]. In the circumstance of local resection with tumor extension beyond the submucosa, it may be prudent to consider more frequent follow-up with imaging surveillance for possible recurrence.

Researchers have attempted to elucidate tumor characteristics, such as Bcl-2 and p53 biomarkers, proliferative index with Ki-67 immunolabeling, mitotic index, and necrosis that may serve as prognostic factors. Aside from primary tumor extent, as detailed above, these have not demonstrated an association with metastatic potential[9,18,28]. Concordantly, even in the single case of rapidly progressive metastatic GP with a lethal course, authors report a Ki-67 labeling index of less than 1% in both the primary and metastatic tumor[16]. One case of appendiceal GP, while not found to have nodal or distant metastases, did present with microscopically aggressive features, including infiltrative margins with extension to the visceral peritoneum, tumor cell necrosis, and a mitotic rate of 3 per 10 high power fields. Tumor cells still did not demonstrate reactivity for Bcl-2 or p53[29]. In a recent case report and literature review by Wang et al[18], they offer increased mast cell accumulation in tumor stroma as a potential marker for aggressive behavior. They describe two cases of GP, one with metastatic disease and one without, in which increased mast cells were identified in the case with metastatic disease[18]. As a follow-up, we have performed CD117 immunohistochemistry on the current case presented, which showed a mild mast cell infiltration within the tumor stroma (focally up to 15 per hpf, with most of the tumor < 5 per hpf). While ours is only one case, we are unable to corroborate mast cells as a marker of aggressive behavior.

In 2011, Barret et al[12] suggested a treatment algorithm based on size of the primary tumor and lymph node status. They suggested local resection for tumors < 2 cm without evidence of lymph node involvement on CT scan. For larger tumors, suspicious lymph nodes, infiltrative margins upon local resection, nuclear pleomorphism, or high mitotic activity, they suggested pancreaticoduodenectomy with lymph node dissection[12]. While we do not dispute these suggestions, we believe that aggressive lymph node dissection beyond what is typically removed during a Whipple procedure is likely unnecessary. Depending on tumor location, some patients may be better served by local resection of the mass and individual grossly metastatic lymph nodes.

In our survey, only 5 (surgical procedure not reported in Micev et al[30] abstract) of the 31 patients were not treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy. One patient underwent excision of the duodenal tumor, ampulla, and peripancreatic lymph node. The pancreatic duct was then sutured to the duodenum. The patient remained disease-free at 20 mo[7]. The second patient, discussed earlier, underwent resection of a duodenal mass, retropancreatic mass, enlarged portal lymph nodes, and part of a hepatic lesion. At eight months, his disease was restricted to the residual hepatic tumor[15]. The third patient had an initial local resection for tumor located in the 2nd portion of the duodenum and was found to have recurrent disease 11 years later in the mesentery, which was treated with resection of the 4th portion of the duodenum, proximal jejunum, and a mesenteric mass[5]. The fourth patient presented with functional tumor as discussed above, underwent initial FNA revealing histology consistent with a GP, then subsequently underwent ampullectomy with a periduodenal and retropancreatic lymph node dissection. Unfortunately, he had return of symptoms and lymphadenopathy at 3 mo, but was lost to follow-up[19]. Finally, the fifth patient was reported simply to have undergone local resection without detail of the surgical approach[31]. Though we report on a very small population of patients, we are encouraged by the nearly uniformly favorable outcomes, regardless of the surgical approach taken, and emphasize the necessity for close follow-up.

Some authors have questioned the necessity for aggressive therapy, even in the case of metastatic disease. Rowsell et al[13] report a case of GP with two lymph node metastases as well as enumerable liver metastases. The primary and lymph node lesions were removed, while the liver lesions were treated conservatively with octreotide injections, and the patient exhibited stable disease at 27 mo. Authors offer that these lesions may be better described as tumors of “uncertain malignant potential[13]”. Another author describes a patient with metastatic disease in four lymph nodes as having “lymph node invasion of uncertain significance[8]”. Considering that patients tend to do well regardless of disease extent, one could conclude that surgical treatment in the case of asymptomatic disease may be too aggressive, particularly for patients who are poor surgical candidates. Conversely, for medically fit patients, surgical resection appears to be curative. It would require long periods of surveillance to answer this question, however.

Correct diagnosis is of great importance when planning surgical treatment and follow-up, as GPs seem to behave in a very indolent fashion and generally carry an excellent prognosis. Diagnosis depends on the presence of three cellular components: Epithelioid endocrine cells, ganglion-like cells, and spindle-like sustentacular cells. In addition to assessing cellular morphology with routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, a wide variety of immunohistochemical stains have been used. The stains used most commonly were S-100, CG, SYN, SS, CK, NSE, NF, and PP. The staining patterns found in our survey are consistent with those of Okubo et al[28]. In their 2011 literature survey, they include a table summarizing immunohistochemical findings from 173 duodenal gangliocytic paragangliomas[28]. As their study population is much larger than ours, we would defer to their findings for more accurate estimates of antibody sensitivities and specificities. While immunohistochemical stains can be performed to aid in recognizing the three cellular components, the histomorphologic features are typically sufficient for diagnosis.

Several reported cases have employed the use of cytology in the initial diagnostic evaluation. Of the 31 cases detailed here, 8 patients underwent fine needle aspiration (FNA) at some point. In one case, FNA of a pancreatic head mass was suggestive of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, prompting a pancreaticoduodenectomy[6]. In another patient found to have segmental groove pancreatitis secondary to a compressive ampullary GP, the initial FNA of a cystic mass-like lesion in the head of the pancreas was determined to be consistent with pancreatitis. FNA of the actual tumor was not performed[25]. In the remaining six cases, FNA was either diagnostic of a GP or carcinoid/neuroendocrine tumor[12,14,19,26,32]. While the epithelioid cellular population seems to predominate, all three cell types have been observed on cytology, and thus may be very helpful in making a pre-surgical diagnosis of GP. Dustin et al[14] and Lei et al[19] offer more complete cytological descriptions of the lesion, and Dustin et al[14] advocates the utility of cytology in initial assessment. They also discuss the use of immunohistochemistry performed on an adequate cell block to help distinguish GP from other lesions in the differential diagnosis, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumor, paraganglioma, leiomyoma, and schwannoma[14,19].

In a 2007 literature review by Witkiewicz et al[2], they point out that the incidence of malignant cases of GP may be underestimated, as most cases have been treated by simple local resection[2]. We summarize our management recommendations in Table 3. Briefly, upon discovery of a periampullary duodenal mass, we recommend endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) or CT imaging to assess extent of disease before proceeding with surgical treatment. While not specifically described in the cases herein, EUS may also be helpful in evaluating for an infiltrative border, raising suspicion for tumor extent beyond the submucosa (the only reliable association with lymph node involvement). We also advocate the use of cytology when clinically appropriate. Though diagnostic confidence will vary depending on cellular yield and composition, it has repeatedly resulted in either a positive diagnosis or a narrowed differential. Most importantly, in the event of a tumor arising near the pancreas, FNA biopsy may help rule out pancreatic adenocarcinoma, and thus the need for neoadjuvant therapy. Based on our literature review, achieving a surgical resection without residual disease seems to be curative. As such, we believe a strong argument can be made for an aggressive surgical approach to eradicate all tumor in patients who are good surgical candidates. There are very few reports of patients treated with chemotherapy or radiation. From these limited examples, this low-grade tumor seems to be poorly-responsive, highlighting the importance of primary surgical eradication. In the event that a complete surgical resection cannot be achieved or attempted (due to extensive metastatic disease or poor surgical candidacy), medical management with a somatostatin analogue should be trialed.

| Ampullary/ periampullary mass | EUS with FNA to rule out pancreatic adenocarcinoma, followed by pancreaticoduodenectomy with resection of suspicious lymph nodes |

| Duodenal mass, away from pancreas | CT to evaluate disease extent +/- FNA with local resection of primary tumor and suspicious lymph nodes if tumor location permits |

| Complete resection unattainable and/or surgically unfit candidate | Imaging modality + FNA/biopsy to establish diagnosis, octreotide scan, and trial of medical management with somatostatin analogues |

| Tumor debulking should be attempted if surgically fit |

In conclusion, we describe a case of duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with metastasis to three regional lymph nodes that was effectively treated with pancreaticoduodenectomy. We also summarize other reported cases of GP with metastasis to further aid in diagnosis and management of this rare disease. While management guidelines are undefined, we emphasize the importance of pre-surgical assessment with imaging studies and FNA to rule out pancreatic adenocarcinoma in the case of peripancreatic lesions, as well as post-surgical follow-up surveillance for disease recurrence. In medically fit candidates, we strongly advocate surgical management to remove all primary and metastatic disease, as achievement of a complete surgical resection appears to be curative.

A 62-year-old man was found to have an asymptomatic duodenal mass on routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus.

A submucosal periampullary duodenal mass without ulceration protruded into the intestinal lumen.

Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, lipoma, neuroendocrine tumor, paraganglioma, gangliocytic paraganglioma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor, leiomyoma, schwannoma, Brunner’s gland adenoma, fibroma.

Preoperative complete blood count and metabolic panel were unremarkable.

Computed tomography showed a well-circumscribed, intraluminal 2.1 cm × 1.4 cm duodenal mass with mild enhancement and no discernable pathologic lymphadenopathy.

Fine needle aspiration demonstrated a neuroendocrine tumor, and the final diagnosis of gangliocytic paraganglioma (GP) with lymph node metastases was made on the pancreaticoduodenectomy specimen.

Complete surgical resection with pancreaticoduodenectomy.

The authors report 30 additional cases of duodenal/head of pancreas GP with metastases, which generally have an excellent prognosis regardless of disease extent at the time of diagnosis, with only a single case of disease-related mortality.

Duodenal GP is a rare tumor of low-malignant potential most often arising in the second portion of the duodenum. It is defined by the presence of three histological components: Epithelioid cells, ganglion-like cells, and spindle-like sustentacular cells.

Aggressive surgical management for this lesion is recommended, as achieving a complete resection of the primary tumor and metastases seems to be curative. If a complete resection cannot be attained (due to either extensive disease or poor surgical candidacy) tumor debulking and/or medical management with somatostatin analogues should be considered.

This is an interesting case report and collective review of previous case reports on paraganglionoma with lymph node metastasis. The manuscript describes well the characterictics, clinical and pathological picture, and also the therapy of a rare duodenal tumor.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fu DL, Isaji S, Kelemen D S- Editor: Gong ZM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Sundararajan V, Robinson-Smith TM, Lowy AM. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:e139-e141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Witkiewicz A, Galler A, Yeo CJ, Gross SD. Gangliocytic paraganglioma: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1351-1354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bucher P, Mathe Z, Bühler L, Chilcott M, Gervaz P, Egger JF, Morel P. Paraganglioma of the ampulla of Vater: a potentially malignant neoplasm. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:291-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Inai K, Kobuke T, Yonehara S, Tokuoka S. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis in a 17-year-old boy. Cancer. 1989;63:2540-2545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dookhan DB, Miettinen M, Finkel G, Gibas Z. Recurrent duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastases. Histopathology. 1993;22:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Henry C, Ghalel-Méchaoui H, Bottero N, Pradier T, Moindrot H. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the pancreas with bone metastasis. Ann Chir. 2003;128:336-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Büchler M, Malfertheiner P, Baczako K, Krautzberger W, Beger HG. A metastatic endocrine-neurogenic tumor of the ampulla of Vater with multiple endocrine immunoreaction--malignant paraganglioma? Digestion. 1985;31:54-59. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Mann CM, Bramhall SR, Buckels JA, Taniere P. An unusual case of duodenal obstruction-gangliocytic paraganglioma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:562-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Okubo Y, Yokose T, Tuchiya M, Mituda A, Wakayama M, Hasegawa C, Sasai D, Nemoto T, Shibuya K. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma showing lymph node metastasis: a rare case report. Diagn Pathol. 2010;5:27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saito J, Hirata N, Furuzono M, Nakaji S, Inase M, Nagano H, Iwata M, Tochitani S, Fukatsu K, Fujii H. A case of duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;107:639-648. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Uchida D, Ogawa T, Ueki T, Kominami Y, Numata N, Matsusita H, Morimoto Y, Nakarai A, Ota S, Nanba S. [A case of gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymphoid metastasis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;107:1456-1465. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Barret M, Rahmi G, Duong van Huyen JP, Landi B, Cellier C, Berger A. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis and an 8-year follow-up: a case report. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:90-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rowsell C, Coburn N, Chetty R. Gangliocytic paraganglioma: a rare case with metastases of all 3 elements to liver and lymph nodes. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2011;15:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Dustin SM, Atkins KA, Shami VM, Adams RB, Stelow EB. The cytologic diagnosis of gangliocytic paraganglioma: a case report. Diagn Cytopathol. 2013;41:650-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Amin SM, Albrechtsen NW, Forster J, Damjanov I. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of duodenum metastatic to lymph nodes and liver and extending into the retropancreatic space. Pathologica. 2013;105:90-93. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Li B, Li Y, Tian XY, Luo BN, Li Z. Malignant gangliocytic paraganglioma of the duodenum with distant metastases and a lethal course. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:15454-15461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shi H, Han J, Liu N, Ye Z, Li Z, Li Z, Peng T. A gangliocytic patially glandular paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9:63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang B, Zou Y, Zhang H, Xu L, Jiang X, Sun K. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma: report of two cases and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:9752-9759. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Lei L, Cobb C, Perez MN. Functioning gangliocytic paraganglioma of the ampulla: clinicopathological correlations and cytologic features. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;7:S107-S113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hashimoto S, Kawasaki S, Matsuzawa K, Harada H, Makuuchi M. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the papilla of Vater with regional lymph node metastasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1216-1218. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Choi SB, Park PJ, Han HJ, Kim WB, Song TJ, Choi SY. A case of duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with regional lymph node metastasis. Americas Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Association. 2014;. |

| 22. | Tomic S, Warner T. Pancreatic somatostatin-secreting gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastases. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:607-608. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Wong A, Miller AR, Metter J, Thomas CR. Locally advanced duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma treated with adjuvant radiation therapy: case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2005;3:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Korbi S, Kapanci Y, Widgren S. Malignant paraganglioma of the duodenum. Immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study of a case. Ann Pathol. 1987;7:47-55. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Fiscaletti M, Fornelli A, Zanini N, Fabbri C, Collina G, Lega S, Stasi G, Jovine E. Segmental groove pancreatitis and duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis: a newly described association. Pancreas. 2011;40:1145-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Sun Y, Kindelberger D, Xu H. Periampullary Gangliocytic Paraganglioma With Lymph Node Involvement: A Case Report. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144:A347. |

| 27. | Ogata S, Horio T, Sugiura Y, Aiko S, Aida S. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with regional lymph node metastasis and a glandular component. Pathol Int. 2011;61:104-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Okubo Y, Wakayama M, Nemoto T, Kitahara K, Nakayama H, Shibuya K, Yokose T, Yamada M, Shimodaira K, Sasai D. Literature survey on epidemiology and pathology of gangliocytic paraganglioma. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Abdelbaqi MQ, Tahmasbi M, Ghayouri M. Gangliocytic paraganglioma of the appendix with features suggestive of malignancy, a rare case report and review of the literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:1948-1952. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Micev M, Jotanovic J, Cosic Micev M, Kjikic Rom A, Bjelovic M, Popovic B, Macut D. Malignant gangliocytic paraganglioma of the ampullary region: a case review. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:S304. |

| 31. | Hu W, Gao S, Chen D, Huang L, Dai R, Shan Y, Zhang Q. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastases: a case report and review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2016;9:4756-4760. |

| 32. | Dowden JE, Staveley KF. Ampullary Gangliocytic Paraganglioma with Lymph Node Metastasis. Pathol Int. 2015;61:104. |

| 33. | Takabayashi N, Kimura T, Yoshida M, Sakuramachi S, Harada Y, Kino I. A case report of duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 1993;26:2444-2448. |