Published online Feb 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i2.46

Peer-review started: September 6, 2016

First decision: October 20, 2016

Revised: November 19, 2016

Accepted: December 1, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: February 16, 2017

Processing time: 163 Days and 14.9 Hours

An 84-year-old woman implanted with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator underwent transvenous lead extraction 4 mo after the implant due to pocket infection. Atrial and right ventricular leads were easily extracted, while the attempt to remove the coronary sinus (CS) lead was unsuccessful. A few weeks later a new extraction procedure was performed in our center. A stepwise approach was used. Firstly, manual traction was unsuccessfully attempted, even with proper-sized locking stylet. Secondly, mechanical dilatation was used with a single inner sheath placed close to the CS ostium. Finally, a modified sub-selector sheath was successfully advanced over the electrode until it was free of the binding tissue. The post-extraction lead examination showed an unexpected fibrosis around the tip. No complications occurred during the postoperative course. Fibrous adhesions could be found in CS leads recently implanted requiring non-standard techniques for its transvenous extraction.

Core tip: Coronary sinus lead extraction is a safe procedure with complication rates comparable to those of the extraction of other leads in experienced centers. The main difficulties may be related to the thickness of the coronary sinus structure and the fibrotic adhesions along it. In this case report we describe an unusual case of persistent fibrosis at the tip of a coronary sinus lead only 4 mo after implantation and the non-standard techniques adopted to achieve successful extraction.

- Citation: Bontempi L, Tempio D, De Vito R, Cerini M, Salghetti F, Dasseni N, Villa C, Raweh A, Inama L, Vassanelli F, Luzi M, Curnis A. Unexpected challenging case of coronary sinus lead extraction. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(2): 46-49

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i2/46.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i2.46

As the number of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices increases, so does the need for coronary sinus (CS) lead extraction, especially because patients with CRT are among those with the highest risk of device related complications[1]. Although there are potential risks of complications associated with the thin wall of the CS and of the afferent branches, CS lead extraction is a safe procedure when performed by experienced professionals due to the generally low rate of adhesions along the coronary vein[2]. We shall describe an uncommon case of fibrotic adhesions at the tip of the CS lead a few months after the implant and the transvenous techniques adopted to successfully extract the lead.

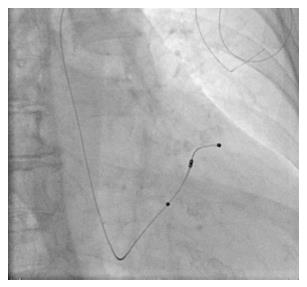

An 84-year-old woman implanted with CRT defibrillator for idiopathic cardiomyopathy underwent a transvenous lead extraction (TLE) 4 mo after the implant due to a local pocket infection with chronic positive blood culture of Staphylococcus Pseudintermedius. Atrial and right ventricular leads were easily extracted, while the attempt to remove the CS lead (Attain® Performa™ Model 4298, Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States) was unsuccessful in the referral center. The patient was then brought to our attention to complete the extraction of the CS lead, in accordance with the current guidelines which set a class I indication to complete system removal in case of device-related infection[3]. The procedure was carried out, under local anesthesia, in our laboratory by two expert interventional electrophysiologists and a cardiac surgeon on standby. Before the procedure, contrast material was administered through the intravenous line, ipsilateral to the site of placement to assess the patency of the subclavian vein. The CS lead was visually examined by fluoroscopy (Figure 1). Two unsuccessful attempts of gentle manual traction (MT) were subsequently performed: The first after the introduction of an Attain Hybrid guidewire (Medtronic) and the second with a locking stylet LLD E (Lead Lock Device Spectranetics, Colorado, United States or Cook Intravascular Inc, IN, United States) advanced as distal as possible. Mechanical dilatation (MD) was then used through a single polypropylene inner sheath with an internal diameter of 8.5 Fr (Cook Intravascular Inc.) advanced up to the CS ostium. Stable traction of the locking stylet still failed to detach the lead; all movements were carefully coordinated in order to avoid injury to the vessel, and especially to the superior vena cava.

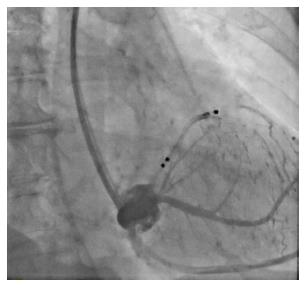

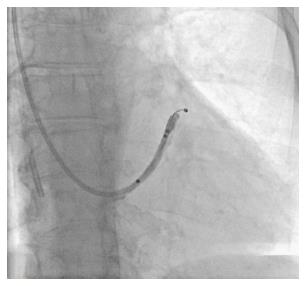

Afterwards, CS was cannulated using an Attain Command™ Delivery System (Medtronic), but due to the inability to reach the tip of the lead, an Attain Select™ sub-selector (Medtronic) was added and advanced inside the CS branch. After both sheaths were successfully inserted, angiographies were performed to verify the integrity of the vascular system (Figure 2). At the sub-selective CS venography, the vessel of the electrode was not visualized. A distal branch occlusion was present, probably due to the development of fibrotic processes (Figure 3).

In order to give more cutting force and increase the shear strength, we decided to cut the sub-selector sheath 1.5 cm from the distal part. With the modified delivery system, the lead was disengaged and pulled back into the sheath.

Despite the short implantation period, the post-extraction examination showed an extended fibrosis on the surface of the lead body (Figure 4). No CS dissection was observed and the postoperative course was uneventful.

We are reporting a difficult CS TLE a few months after the implant, which required challenging MD up to the distal tip of CS lead using both conventional sheaths and modified CS lead delivery due to fibrotic adherence.

Recently, HRS published an expert consensus statement[3] which asserts that the infection of the pocket, device, and/or lead is the most frequent Class I indication for lead removal.

Lead extraction is still a challenging procedure requiring specific expertise. HRS recommends at least 40 cases experience for the physician acting as first operators, whereas a minimum number of 20 annual extractions should be requested[4,5].

A frequent issue found during the lead extraction is the presence of fibrotic processes on body leads, both in vascular and endocardial side. This problem is much more sporadic in the CS, where the only region easily affected by fibrosis is the ostium. However, there is still a great concern about CS extraction because of the potential risk of cardiac tamponade due to CS dissection.

CS leads can be often successfully extracted with direct traction only, as reported by a recent study on 125 leads[6], but literature is not exhaustive.

Nevertheless, in a small percentage of cases, major and possibly life-threatening complications are related to the extraction tools used in the weak CS structure in unfavourable anatomical positions, raising questions regarding the possible need of tools specifically designed for this structure.

In addition, CS leads have different designs, having a smaller body diameter than atrial or ventricular leads with less physical resistance to traction and a higher risk of rupture. In order to avoid lead damage the counter pressure or countertraction maneuvers have to be applied with special care.

Our procedure consisted in the following phases: (1) manual traction was attempted; (2) a locking stylet (LLD E) was put forward along the lumen and locked at the distal part of the lead, then MT was attempted again; (3) as traction was unsuccessful due to unexpected fibrosis, a modified delivery sheath was advanced over the lead until the lead was disengaged from all the tissue at the distal tip of CS lead. Despite our experience in lead extraction[7], in this case removing a CS lead was unexpectedly difficult, not only by MT but also performing MD.

To date, there are no tools specifically designed for CS lead extraction. In order to complete the procedure successfully we had to directly modify a standard CS delivery system to obtain a non-traumatic dissection of local fibrosis.

This case highlights the importance of approaching each single procedure with caution as even a potentially simple case may be challenging for an expert operator.

In conclusion, persistent fibrosis at the tip of a CS lead was found during the extraction procedure 4 mo after implant. A tailored technique consistent of locking stylet MT with a modified sub-selector delivery sheath advanced over the lead in the CS branch was successful.

An 84-year-old woman implanted with cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator had persistent fevers.

The patient presented a pocket infection.

The patient underwent transvenous lead extraction 4 mo after the implant, but difficulties were found in the coronary sinus lead extraction.

The infection presented persistent positive blood culture of Staphylococcus Pseudintermedius.

At the sub-selective coronary sinus venography, the vessel of the electrode was not visualized; a distal branch occlusion was present, probably due to the development of fibrotic processes.

The post-extraction examination showed an extended fibrosis on the surface of the lead body.

A modified sub-selector sheath was successfully advanced over the electrode until it was free of the binding tissue.

Coronary sinus leads can be often successfully extracted with direct traction only, the presence of fibrotic processes on body leads is uncommon in the coronary sinus, in particular after few months from the implant.

A sub-selector sheath is a tool used during resynchronization therapy defibrillator implant to reach and deliver the electrode in the target vessel of the coronary venous system.

Persistent fibrosis at the tip of a coronary sinus lead might be found also few months after implant, a tailored technique with a modified sub-selector delivery sheath advanced over the lead in the coronary sinus branch allowed to complete the extraction procedure.

This is a rare case report about coronary sinus lead extraction using new techniques. This manuscript is nicely structured and well written.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Italy

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Amiya E, Iacoviello M, Kirali K, Ueda H S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | van der Heijden AC, Borleffs CJ, Buiten MS, Thijssen J, van Rees JB, Cannegieter SC, Schalij MJ, van Erven L. The clinical course of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: Extended experience on clinical outcome, device replacements, and device-related complications. Heart Rhythm. 2015;12:1169-1176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kasravi B, Tobias S, Barnes MJ, Messenger JC. Coronary sinus lead extraction in the era of cardiac resynchronization therapy: single center experience. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 2005;28:51-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Byrd CL, Bongiorni MG, Carrillo RG, Crossley GH, Epstein LM, Friedman RA, Kennergren CE, Mitkowski P. Transvenous lead extraction: Heart Rhythm Society expert consensus on facilities, training, indications, and patient management: this document was endorsed by the American Heart Association (AHA). Heart Rhythm. 2009;6:1085-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 744] [Cited by in RCA: 789] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smith HJ, Fearnot NE, Byrd CL, Wilkoff BL, Love CJ, Sellers TD. Five-years experience with intravascular lead extraction. U.S. Lead Extraction Database. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1994;17:2016-2020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bracke FA, Meijer A, Van Gelder B. Learning curve characteristics of pacing lead extraction with a laser sheath. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1998;21:2309-2313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sheldon S, Friedman PA, Hayes DL, Osborn MJ, Cha YM, Rea RF, Asirvatham SJ. Outcomes and predictors of difficulty with coronary sinus lead removal. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2012;35:93-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bontempi L, Vassanelli F, Lipari A, Locantore E, Cassa MB, Salghetti F, Elmaghawry M, Vizzardi E, D’Aloia A, Mahmudov R. Extraction of a coronary sinus lead: always so easy? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2014; Jul 21; Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |