Published online Dec 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i12.440

Peer-review started: July 20, 2017

First decision: September 4, 2017

Revised: September 29, 2017

Accepted: October 29, 2017

Article in press: October 29, 2017

Published online: December 16, 2017

Processing time: 141 Days and 11.1 Hours

This report presents a case of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS) located in the left maxillary sinus and invading the orbital cavity in a ten-year-old male patient who was treated at a referral hospital. The images provided from the computed tomography showed a heterogeneous mass with soft-tissue density, occupying part of the left half of the face inside the maxillary sinus, and infiltrating and destroying the bone structure of the maxillary sinus, left orbit, ethmoidal cells, nasal cavity, and sphenoid sinus. An analysis of the histological sections revealed an undifferentiated malignant neoplasm infiltrating the skeletal muscle tissue. The immunohistochemical analysis was positive for the antigens: MyoD1, myogenin, desmin, and Ki67 (100% positivity in neoplastic cells), allowing the identification of the tumour as an eRMS. The treatment protocol included initial chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy and finally surgery. The total time of the treatment was nine months, and in 18-mo of follow-up period did not show no local recurrences and a lack of visual impairment.

Core tip: This case report is important because it describes the diagnosis trajectory of a rhabdomyosarcoma located in an uncommon region, presenting the steps of the exams performed and their results. The knowledge must be realized with the intention of improving the diagnosis and the clinical conduct, giving greater survival rate and better quality of life to the patient. The early diagnosis was very important in this case, due to the imaging and histopathological exams in question with the association of experienced pathologists.

- Citation: de Melo ACR, Lyra TC, Ribeiro ILA, da Paz AR, Bonan PRF, de Castro RD, Valença AMG. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma in the maxillary sinus with orbital involvement in a pediatric patient: Case report. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(12): 440-445

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i12/440.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i12.440

Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is a malignant mesenchymal tumour of the skeletal myogenic fibres[1,2] and is considered the most common soft-tissue tumour in children and adolescents, responsible for 50% of all soft-tissue sarcomas. It is the second most common paediatric tumour of the head and neck (after lymphoma) and is most commonly located in the cervical-cephalic region or the genitourinary system[3-5].

RMS is histologically classified as embryonal (eRMS), alveolar (aRMS), pleomorphic (pRMS) and spindle cells and sclerotic type (eRMS). The first two subtypes occur in children and adolescents, with the alveolar subtype being more aggressive than the embryonal subtype, while pleomorphic RMS affects adults[5,6]. The first two subtypes (eRMS and aRMS) are diagnosed based on the expression of myogenic markers, such as transcription factors, MyoD, myogenin, myosin heavy-chain structural proteins, skeletal a-actin, and desmin. These markers connect RMS to a skeletal-muscle lineage, but the tumour may also originate from a non-myogenic cell[5,7]. Thus, although RMS usually originates from within a skeletal muscle, it can also develop in areas devoid of muscle tissue, such as the salivary glands, skull base, biliary tree, and genitourinary tract[5,7,8].

Although some eRMS cases were reported before, few cases presented a complete clinical, imaginologic and microscopic documentation, including follow up description. The present study reports a case of eRMS in the left maxillary sinus with invasion of the orbital cavity in a paediatric patient diagnosed and treated at the Hospital Napoleão Laureano in João Pessoa, PB, Brazil.

The patient (10 years old, male, mixed race) was admitted to the Hospital Napoleão Laureano, which is a referral hospital for cancer diagnosis and treatment in Paraíba State, presenting with a large swelling and exophthalmos on the left side of the face in addition to a raised and hardened area in the maxillary region that had appeared approximately 25 d prior. The patient presented no fever and reported feeling pain occasionally. The patient’s visual acuity, eye structure, and ocular fundus were normal in both eyes (Figure 1).

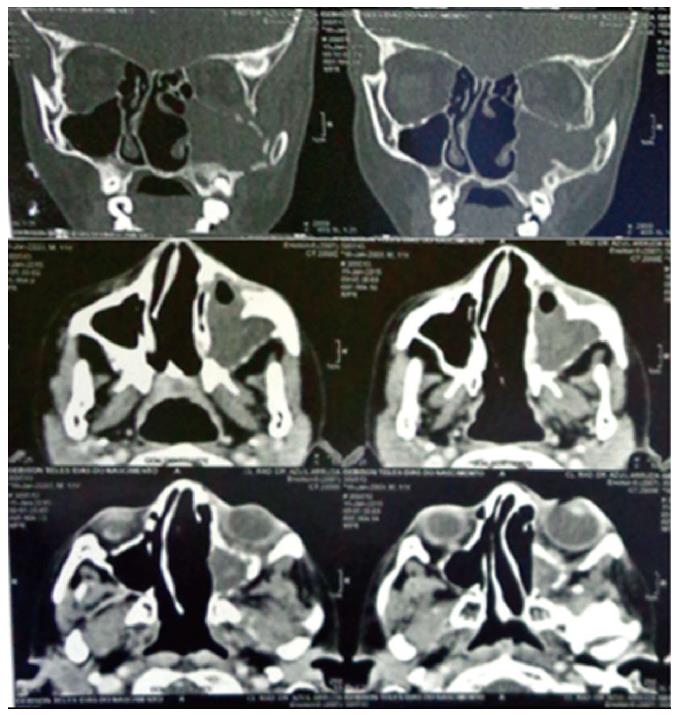

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the paranasal sinuses was performed with and without intravenously administered contrast. The images showed a heterogeneous (DM = 32 UH) mass with soft-tissue density, measuring 1.5 cm × 6.2 cm × 5.0 cm, occupying part of the left half of the face inside the maxillary sinus, and infiltrating and destroying the bone structure of the maxillary sinus, left orbit, ethmoidal cells, nasal cavity, and sphenoid sinus. Inflammatory sinus disease was present in the left maxillary sinus and left exophthalmos due to the compression exerted on the eye (Figure 2).

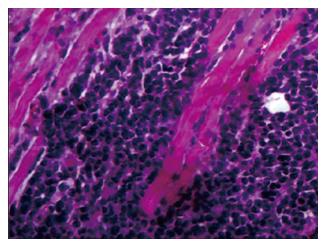

Through an incisional biopsy, an oval tissue fragment of light-brown colour and firm-elastic consistency, measuring 1 cm × 0.8 cm × 0.6 cm, was collected from inside the left maxillary sinus. An analysis of the histological sections revealed an undifferentiated malignant neoplasm infiltrating the skeletal muscle tissue (Figure 3).

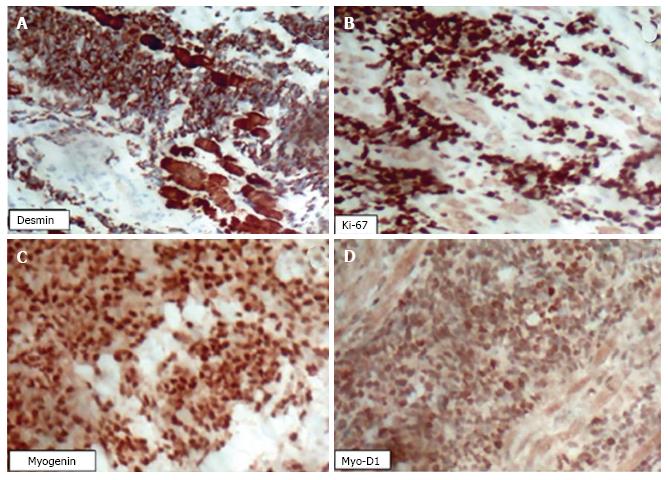

An immunohistochemical analysis was performed on a biopsied tumour fragment from the left maxillary sinus. The paraffin block was cut into 3-μm sections, which were analysed using an automated method (Ventana Benchmark GX, Roche Diagnostics) with a multimetric detection system (Ventana ultraView Universal DAB detection Kit, Roche Diagnostics). Positive and negative controls confirmed the reliability of the methods. The microscopic examination was positive for the following antigens: MyoD1, myogenin, desmin, and Ki67 (100% positivity in neoplastic cells) (Figure 4), allowing the identification of the tumour as an eRMS.

The treatment plan combined chemotherapy with radiation therapy; chemotherapy was initially performed for a nine-month period (Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide), combined with 20 radiation fractions (50.4 Gy), and followed by surgical ablation of residual mass on maxillary sinus with ocular globe and optic nerve preservation.

After 2.5 mo of chemotherapy, there was a significant reduction of the tumour mass (Figure 5A). After completion of the treatment (9 mo), the patient progressed satisfactorily and, during the follow-up period to date (18 mo), has shown no visual impairment or tumour manifestation in any other region (Figure 5B).

The incidence of eRMS is highest in children one to four years old, lower among those 10-14 years old, and lowest among those 15-19 years old[9-11]. The head and neck region is a common site for the development of eRMS. The orbit is the most frequent site[9,12] and is also a common location for tumour extensions of the same histopathology occurring in adjacent cavities[13], such as the maxillary sinus, as reported in the present case.

The cytogenetic characterisation of eRMS is not well established; however, in ≥ 80% of cases, aRMS is associated with chromosomal translocations between chromosomes 2 and 13 [t (2; 13) (q35; q14)] or chromosomes 1 and 13 [t (1; 13) (q36; q14)] and genetic imbalances that result in the fusion of domains of the transcription factors Pax3 and Pax7 with FOXO1a[2,5,14-16].

The final diagnosis is usually defined based on a tissue biopsy associated with a histopathological and immunohistochemical study[17]. Both aRMS and eRMS express myogenin and MyoD1 (myogenic regulatory nuclear proteins), but the alveolar subtype shows stronger and more generalised myogenin expression than eRMS. The diagnosis of RMS subtypes is important because aRMS is associated with a poorer prognosis, with a greater frequency of disseminated metastases. The immunohistochemical staining of pediatric RMS with antibodies to MyoD and myogenin provides information for a definitive diagnosis. Although almost all cases show nuclear expression of both products, staining for myogenin shows greater clinical utility due to its consistency and association with less nonspecific staining[17].

While it is desirable that pediatric tumours should be identified in their early stages to obtain the best prognosis, the reality is that early diagnosis does not occur in many cases. Additionally, the rapid growth of pediatric tumours makes medical management challenging for combating tumour growth and the complications that can arise from an advanced-stage tumour[18].

The rapid growth of tumour masses in the ocular region, whether derived from the paranasal tissues or otherwise, has been reported in other studies[19,20]. In a case reported by Magrath et al[19], a three-year-old male patient also showed swelling in the left eye; however, the tumour dimensions were smaller than those reported here. The growth period was also approximately four weeks; however, the growth originated within the orbit rather than arising from the maxillary sinus tissues, as in the present case. Furthermore, the initial characteristics were consistent with a framework of cellulitis, the aRMS diagnosis was obtained through immunohistochemistry, and tumour remission occurred after one month of treatment with Vincristine, Dactinomycin, and Cyclophosphamide. In a case reported by Chen et al[20], the patient was also male and was 13 years old. Exophthalmos of the left eye developed gradually over a two-week period until a doctor was consulted. Upon examination, the patient was diagnosed with aRMS, with destruction of the ethmoid bone, nasal cavity, and orbital cavity but without evidence of distant metastases. A combined treatment protocol consisting of chemotherapy (Vincristine + Actinomycin + Cyclophosphamide) and radiotherapy for high-risk RMS was initiated. After 44 wk of treatment, the tumour regressed completely, and no recurrence was observed at one year after the completion of treatment.

A retrospective analysis of the records of 14 patients by Fyrmpas et al[13] showed that the average age of patients with RMS of the sinuses was 7.5 years and that 42.8% underwent surgery before beginning chemotherapy, while 57.2% received chemotherapy and radiation. In addition, intracranial extension and ages greater than 10 years were associated with lower than average survival rates (five-year survival rates, 53.9% for all patients and 83.3% for those who underwent surgery).

The clinical differential diagnosis may be performed with others aggressive connective tissue malignant lesions as Fibrosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma and Leiomyosarcoma. The final diagnosis is realized through microscopic tests. The prognosis of rhabdomyosarcoma is evaluated according to its clinical, anatomical, histopathological and age characteristics. Normally, the sRMS and aRMS have a good and poor prognosis, respectively. The eRMS of the present case is classified as having an intermediate prognosis lesion[21].

In general, the management of pediatric RMS requires a combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and surgery. Chemotherapy is the first and most important approach to advanced-stage tumours, such as that described here. Tumours diagnosed at an early stage can be treated with a radical surgical approach because the function and cosmetic appearance can possibly be preserved.

This paper focused a single clinical case which could not be extrapolated to all cases of RMS on head and neck. However, due to scarcity of analogous clinical cases and needing to better comprehend this condition, this report could be useful for clinical practice, including differential diagnosis options and diagnosis by clinical or microscopic similarities. It is vital that health professionals are aware of the early signs of cancer in paediatric patients and have sufficient knowledge of efficient referral procedures to paediatric cancer diagnosis and treatment units so that children and adolescents will not suffer the consequences of late diagnosis and receive a less aggressive treatment approach.

The patient presented occasionally pain, large swelling and exophthalmos on the left side of the face in addition to a raised and hardened area in the maxillary region that had appeared approximately 25 d prior.

According to the clinical examination, the patient’s visual acuity, eye structure, and ocular fundus were normal in both eyes.

The differential diagnosis are others aggressive connective tissue malignant lesions as Fibrosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma and Leiomyosarcoma.

The computed tomography showed a heterogeneous mass occupying part of the left half of the face inside the maxillary sinus, and infiltrating and destroying the bone structure of the maxillary sinus, left orbit, ethmoidal cells, nasal cavity, and sphenoid sinus.

An analysis of the histological sections revealed an undifferentiated malignant neoplasm infiltrating the skeletal muscle tissue.

The treatment plan combined chemotherapy with radiation therapy and followed by surgical ablation of residual mass on maxillary sinus with ocular globe and optic nerve preservation.

To our knowledge, there aren’t many papers about embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma (eRMS) that describes pathological, immunohistochemical and surgical findings of a clinical case in the literature.

Regarding the trajectory of this case, everything occurred according to the terms.

This report helps to further understand eRMS in terms of diagnosis, clinical presentation, treatment and prognosis.

This is a well written case report.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Akbulut S, Alimehmeti RH, Brcic I, Kute VB S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Reilly BK, Kim A, Peña MT, Dong TA, Rossi C, Murnick JG, Choi SS. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in children: review and update. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;79:1477-1483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tandon A, Sethi K, Pratap Singh A. Oral rhabdomyosarcoma: A review. J Clin Exp Dent. 2012;4:e302-e308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sengupta S, Pal R, Saha S, Bera SP, Pal I, Tuli IP. Spectrum of head and neck cancer in children. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2009;14:200-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garay M, Chernicoff M, Moreno S, Pizzi de Parra N, Oliv , J , Apréa G. Rabdomiosarcoma alveolare congenito in un neonato. Eur J Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;14:9-12. |

| 5. | Keller C, Guttridge DC. Mechanisms of impaired differentiation in rhabdomyosarcoma. FEBS J. 2013;280:4323-4334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Perez EA, Kassira N, Cheung MC, Koniaris LG, Neville HL, Sola JE. Rhabdomyosarcoma in children: a SEER population based study. J Surg Res. 2011;170:e243-e251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hatley ME, Tang W, Garcia MR, Finkelstein D, Millay DP, Liu N, Graff J, Galindo RL, Olson EN. A mouse model of rhabdomyosarcoma originating from the adipocyte lineage. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:536-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gurney JG. Topical topics: Brain cancer incidence in children: time to look beyond the trends. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1999;33:110-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Shrutha SP, Vinit GB. Rhabdomyosarcoma in a pediatric patient: A rare case report. Contemp Clin Dent. 2015;6:113-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | França CM, Caran EM, Alves MT, Barreto AD, Lopes NN. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the oral tissues--two new cases and literature review. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:E136-E140. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Gordón-Núñez MA, Piva MR, Dos Anjos ED, Freitas RA. Orofacial rhabdomyosarcoma: report of a case and review of the literature. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2008;13:E765-E769. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hicks J, Flaitz C. Rhabdomyosarcoma of the head and neck in children. Oral Oncol. 2002;38:450-459. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fyrmpas G, Wurm J, Athanassiadou F, Papageorgiou T, Beck JD, Iro H, Constantinidis J. Management of paediatric sinonasal rhabdomyosarcoma. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:990-996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Barr FG. Molecular genetics and pathogenesis of rhabdomyosarcoma. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1997;19:483-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Davis RJ, D’Cruz CM, Lovell MA, Biegel JA, Barr FG. Fusion of PAX7 to FKHR by the variant t(1;13)(p36;q14) translocation in alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2869-2872. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Galili N, Davis RJ, Fredericks WJ, Mukhopadhyay S, Rauscher FJ 3rd, Emanuel BS, Rovera G, Barr FG. Fusion of a fork head domain gene to PAX3 in the solid tumour alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat Genet. 1993;5:230-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 656] [Cited by in RCA: 678] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sebire NJ, Malone M. Myogenin and MyoD1 expression in paediatric rhabdomyosarcomas. J Clin Pathol. 2003;56:412-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Grabois MF, Oliveira EX, Carvalho MS. Childhood cancer and pediatric oncologic care in Brazil: access and equity. Cad Saude Publica. 2011;27:1711-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Magrath GN, Cheeseman EW, Eiseman AS, Caplan MJ. A rapidly expanding orbital lesion. J Pediatr. 2013;163:294-295.e1-2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chen SC, Bee YS, Lin MC, Sheu SJ. Extensive alveolar-type paranasal sinus and orbit rhabdomyosarcoma with intracranial invasion treated successfully. J Chin Med Assoc. 2011;74:140-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Arul AS, Verma S, Arul AS, Verma R. Oral rhabdomyosarcoma-embryonal subtype in an adult: A rarity. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2014;5:222-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |