Published online Dec 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i12.428

Peer-review started: July 6, 2017

First decision: August 4, 2017

Revised: August 25, 2017

Accepted: September 12, 2017

Article in press: September 13, 2017

Published online: December 16, 2017

Processing time: 156 Days and 16.8 Hours

Alpha-thalassemia trait and sickle trait are not commonly considered risk factors of ischemic heart disease. We report the case of a non-atherosclerotic silent myocardial infarction in a 46-year-old woman, carrier of the alpha-thalassemia trait (homozygous deletion of locus -3.7) combined with sickle cell trait. While the patient was included as healthy volunteer for a metabolic study, we performed cardiac magnetic resonance imagery showing a left ventricle apicolateral myocardial infarction. Coronary computed tomography angiography showed normal coronary arteries with a coronary calcium score of 0. The patient was treated with low-dose aspirin in secondary prevention afterwards. This case allows us to discuss cardiovascular risk among patients presenting with both alpha-thalassemia trait and sickle cell trait and the indication of cardiac imagery in such patients even when considered as low-cardiovascular risk.

Core tip: Alpha-thalassemia trait and sickle trait are not considered risk factors of ischemic cardiopathy. We reported the case of a non-atherosclerotic silent myocardial infarction in a 46-year-old woman, carrier of the alpha-thalassemia trait combined with sickle cell trait. While the patient was included as healthy volunteer for a metabolic study, we performed cardiac magnetic resonance imagery showing a left ventricle apicolateral myocardial infarction. Coronary computed tomography angiography showed normal coronary arteries with a null calcium score. The patient was treated with low-dose aspirin in secondary prevention afterwards. This case allows us to discuss cardiovascular risk among patients presenting with alpha-thalassemia trait and sickle cell trait.

- Citation: Nguyen LS, Redheuil A, Mangin O, Salem JE. Sickle-cell and alpha-thalassemia traits resulting in non-atherosclerotic myocardial infarction: Beyond coincidence? World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(12): 428-431

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i12/428.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i12.428

Sickle-cell trait and alpha-thalassemia trait are associated in 10% of sub-Saharan population. Both are asymptomatic. The cardiovascular risk associated with both traits is unknown. We here report the case of a 46-year-old female patient, asymptomatic, who was diagnosed with both traits and a silent non-atherosclerotic myocardial infarction. This case raises the question of performing cardiac imagery in such patients and assessing their cardiovascular risk.

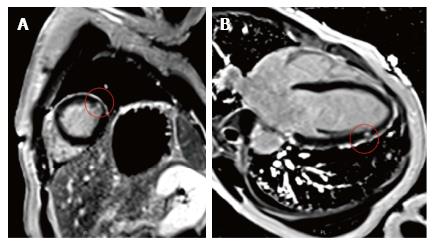

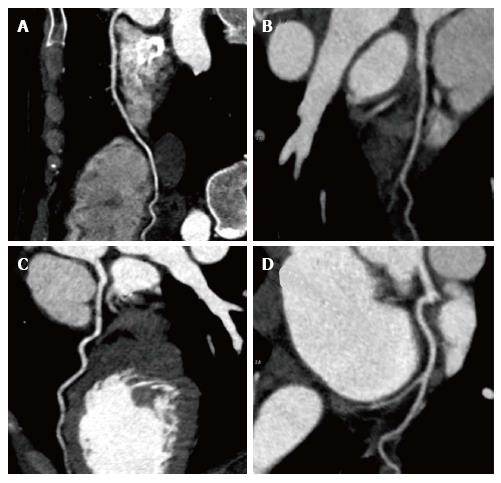

We report the case of a 46-year-old female patient of Erythrean origin who was included as healthy volunteer in a French observational trial on lipid metabolism during which blood analyses and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) were performed. Presence of myocardial silent infarction was measured using cMRI by evaluating presence and quantification of late gadolinium enhancement (LGE). In addition to LGE, cine SSFP acquisitions were acquired in the left ventricle (LV) to characterize its function and morphology. She had no known prior medical history or cardiovascular symptoms and her only cardiovascular risk factor was a light smoking habit (< 4 pack-years) with normal lipid levels (total-cholesterol = 162 mg/dL, LDL-cholesterol = 94 mg/dL, HDL-cholesterol = 53 mg/dL, triglycerides = 74 mg/dL), normal fasting glucose (4.8 mmol/L) and normal blood pressure (systolic 119 mmHg, diastolic 70 mmHg). Her Framingham risk for cardiovascular ischemic events was very low (less than 1% over 10 years). She had previously been included as a healthy volunteer in other studies and had never been diagnosed with any medical condition. Electrocardiogram (ECG) at inclusion did not show any sign of existing ischemia. Transthoracic echocardiography was considered normal, without any left ventricle wall anomaly. cMRI revealed subendocardial late gadolinium enhancement in one latero-apical segment (Figure 1) compatible with localized silent myocardial infarction. LV mass was 106.2 g (60 g/m2), LV end diastolic and systolic volumes were respectively 168 mL (95.5 mL/m2) and 84 mL (47.7 mL/m2). LV ejection fraction was 50%. Subsequent computed tomography coronary angiography did not show any coronary lesions or plaques and coronary calcium score was 0 (Figure 2). Blood analysis showed normal hemoglobin (Hb) at 13.2 g/dL and Hb electrophoresis revealed a previously unknown HbS proportion of 23.8%. Further genetic analyses finally showed she carried the alpha-thalassemia trait (ATT) (homozygous deletion of locus -3.7) and sickle cell trait (heterozygous for beta-globin mutation 6 Glu-> Val), which had never been diagnosed before. She was later treated in secondary prevention by low-dose aspirin (75 mg/d) and remained asymptomatic during a 6-mo follow-up.

Association between alpha-thalassemia and sickle cell trait is frequent with a 10% estimated prevalence, in sub-Saharan Africa from where our patient originates[1,2]. We hereafter discuss this association with cardiovascular outcomes.

While alpha-thalassemia major and intermedia (= hemoglobin H disease) have been associated with an increased thrombotic risk[3], alpha-thalassemia minor (= alpha-thalassemia trait) is not considered to increase the risk of ischemic or thrombotic events. Similarly, sickle cell disease is associated with non-atherosclerotic myocardial infarction but sickle cell trait has not been shown to be associated with an increased risk of ischemic events[4].

On the other hand, sickle cell trait carriers have an increased risk of sudden death of unclear pathophysiology[5]. This risk is increased during intensive physical exercise. Hypotheses involve a lowering of pH, an increase in body temperature and concomitant dehydration, all thought to initiate intravascular sickling due to HbS polymerization. This may result in an increase of concentrations of deoxygenized HbS leading to diffuse microvascular obstruction[6].

The most prevalent cause of sudden death in this setting is fatal arrhythmia associated with ischemic heart disease[7]. Deriving from our case, we hereafter suggest a potential series of events, which may lead to sudden death among sickle cell trait carriers.

Cardiac MRI, a highly sensitive non-invasive myocardial imaging technique, demonstrated the presence of localized silent myocardial infarction. Mechanisms of infarction which have been suggested in the context of sickle cell trait include: (1) rheological factors of altered viscosity and membrane flexibility contributing to microcirculatory stasis; (2) lower platelet survival during sickle cell crisis; and (3) vasospasm[8].

Our patient being a mild smoker, she had an increased procoagulant state[9]. This prothrombotic, proatherogenic state may in turn have favored the formation of micro-thrombi, especially in the distal portion of the myocardial vasculature. Combining this procoagulant state with sickle cell trait may explain why the infarction remained localized without any other signs of atherosclerosis. This is a common feature of infarction among patients presenting with sickle cell disease[4].

Hence, this myocardial scar may represent a substrate for potential ventricular arrhythmia, with physical exercise increasing the risk of sudden death.

No guideline exists on the use of aspirin for the prophylaxis of ischemic events. A study on prevention of stroke among patients suffering from sickle cell disease is ongoing but results have yet to be published (NCT00178464).

Prognosis of silent myocardial infarction is hard to assess; as by definition, it is asymptomatic. However, with an estimated prevalence of 10% carriers of both sickle-cell and alpha-thalassemia traits in sub-Saharan Africa and a sudden death rate of 0.8/1000 person-year, the annual rate of sudden death associated with this disease would be tremendous.

Coronary artery disease was ruled out by computed tomography coronary angiography, reference imagery in such case of a young woman not presenting with any other cardiovascular risk factor[10].

Silent myocardial infarction can of course be caused by regular cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking in this particular case. Thus, it would be relevant to conduct a large study on carriers of sickle-cell and alpha-thalassemia traits regarding ischemic cardiac disease and independent-related risk factors.

This case raises the importance and pertinence of performing cMRI among asymptomatic patients, and particularly those at higher cardiovascular risk. Patients presenting sickle-cell and alpha-thalassemia traits may be included in this category.

Patient was asymptomatic.

She presented an association of sickle-cell trait and alpha-thalassemia trait, resulting in a silent myocardial infarction.

Myocardial infarction are mostly atherosclerotic, hence, coronary imagery was required.

Hemoglobin electrophoresis confirmed the sickle-cell and alpha-thalassemia trait.

Computed tomography coronary angiography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cMRI) confirmed diagnosis of myocardial infarction and ruled out atherosclerotic cause.

Aspirin was given in secondary prevention.

Lubega et al. Alpha thalassemia among sickle cell anaemia patients in Kampala, Uganda. Afr Health Sci 2015; 15: 682-689.

Alpha-thalassemia trait is also known as alpha-thalassemia minor.

Performing cMRI among asymptomatic patients, such as alpha-thalassemia and sickle-cell trait carriers may be acceptable.

This study features the rare finding of myocardial infarction in a case of sickle cell and alpha-thalassemia traits.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fourtounas C, Kute VBB, Sijens PE, Yoshida S, Wang F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Lubega I, Ndugwa CM, Mworozi EA, Tumwine JK. Alpha thalassemia among sickle cell anaemia patients in Kampala, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15:682-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wambua S, Mwacharo J, Uyoga S, Macharia A, Williams TN. Co-inheritance of alpha+-thalassaemia and sickle trait results in specific effects on haematological parameters. Br J Haematol. 2006;133:206-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Sirachainan N. Thalassemia and the hypercoagulable state. Thromb Res. 2013;132:637-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martin CR, Johnson CS, Cobb C, Tatter D, Haywood LJ. Myocardial infarction in sickle cell disease. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88:428-432. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mitchell BL. Sickle cell trait and sudden death--bringing it home. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:300-305. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kark JA, Posey DM, Schumacher HR, Ruehle CJ. Sickle-cell trait as a risk factor for sudden death in physical training. N Engl J Med. 1987;317:781-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 288] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Myerburg RJ, Junttila MJ. Sudden cardiac death caused by coronary heart disease. Circulation. 2012;125:1043-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 341] [Article Influence: 26.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wilkes D, Donner R, Black I, Carabello BA. Variant angina in an 11 year old boy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985;5:761-764. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Ikonomidis I, Lekakis J, Vamvakou G, Andreotti F, Nihoyannopoulos P. Cigarette smoking is associated with increased circulating proinflammatory and procoagulant markers in patients with chronic coronary artery disease: effects of aspirin treatment. Am Heart J. 2005;149:832-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jacobs JE, Boxt LM, Desjardins B, Fishman EK, Larson PA, Schoepf J; American College of Radiology. ACR practice guideline for the performance and interpretation of cardiac computed tomography (CT). J Am Coll Radiol. 2006;3:677-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |