Published online Jan 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i1.18

Peer-review started: August 25, 2016

First decision: October 28, 2016

Revised: November 11, 2016

Accepted: December 1, 2016

Article in press: December 2, 2016

Published online: January 16, 2017

Processing time: 137 Days and 14.3 Hours

Standard chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for local advanced rectal cancer (LARC) rarely induce rectal perforation. Here we report a rare case of rectal perforation in a patient with LARC in the midst of preoperative CRT. A 56-year-old male was conveyed to our hospital exhibiting general malaise. Colonoscopy and imaging tests resulted in a clinical diagnosis of LARC with direct invasion to adjacent organs and regional lymphadenopathy. Preoperative 5-fluorouracil-based CRT was started. At 25 d after the start of CRT, the patient developed a typical fever. Computed tomography revealed rectal perforation, and he underwent emergency sigmoid colostomy. At 12 d after the surgery, the remaining CRT was completed according to the original plan. The histopathological findings after radical operation revealed a wide field of tumor necrosis and fibrosis without lymph node metastasis. We share this case as important evidence for the treatment of LARC perforation in the midst of preoperative CRT.

Core tip: Standard chemoradiotherapy (CRT) for local advanced rectal cancer (LARC) rarely induces rectal perforation. This case report presents a case of rectal perforation in a patient with LARC in the midst of 5-fluorouracil-based preoperative CRT. We decided to complete CRT according to the original plan after supporting emergency recovery. The histopathological findings after radical operation revealed a wide field of tumor necrosis and fibrosis without lymph node metastasis, suggesting the efficacy of the CRT. We believe that establishing a standard treatment for CRT-related LARC perforation may improve the prognosis of such cases.

- Citation: Takase N, Yamashita K, Sumi Y, Hasegawa H, Yamamoto M, Kanaji S, Matsuda Y, Matsuda T, Oshikiri T, Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Koma YI, Komatsu M, Sasaki R, Kakeji Y. Local advanced rectal cancer perforation in the midst of preoperative chemoradiotherapy: A case report and literature review. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(1): 18-23

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i1/18.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i1.18

Currently, the best proven approach to local advanced rectal cancer (LARC) is a combination of surgery and preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT)[1,2]. Compared to preoperative radiotherapy (RT) alone, the incidence of local recurrence at 5 years was significantly lower in the preoperative CRT group[3]. We previously reported that the pathological response to preoperative 5-fluorouracil (FU)-based CRT may be a useful predictor of LARC survival[4]. However, preoperative CRT is associated with various adverse effects that can be life-threatening. Among the life-threatening side effects, CRT-related perforation of colorectal cancer is not well understood. We herein report a case of perforated LARC associated with preoperative CRT.

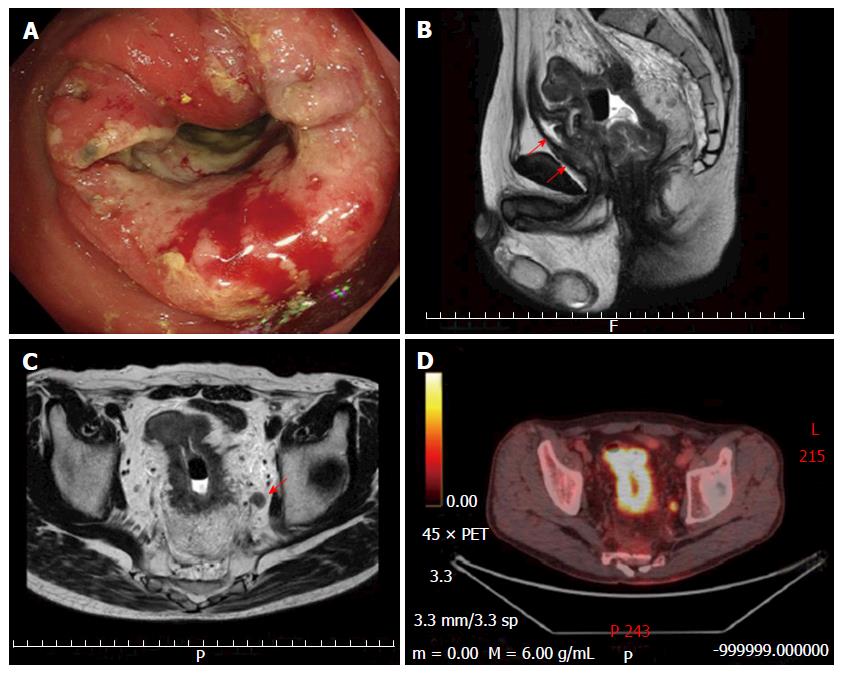

A 56-year-old Japanese male was transported to our facility with chief complaints of fever and general malaise. Though he had had anemia 3 years prior, he did not seek medical attention. He had used alcohol for at least 34 years. His serum level of carcino embryonic antigen was increased to 21.0 ng/mL (normal < 2.5). The colonoscopy examination revealed a low anterior circumferential rectal lesion (Figure 1A).

An endoscopic biopsy histologically confirmed the clinical diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings revealed LARC with involvement of perirectal fat, the prostate and the seminal vesicles (Figure 1B). Some of the lymph nodes in the tumor area were enlarged (Figure 1C) and 18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) showed metabolically active foci in the left obturator lymph node (Figure 1D). No evidence of distant spread was seen.

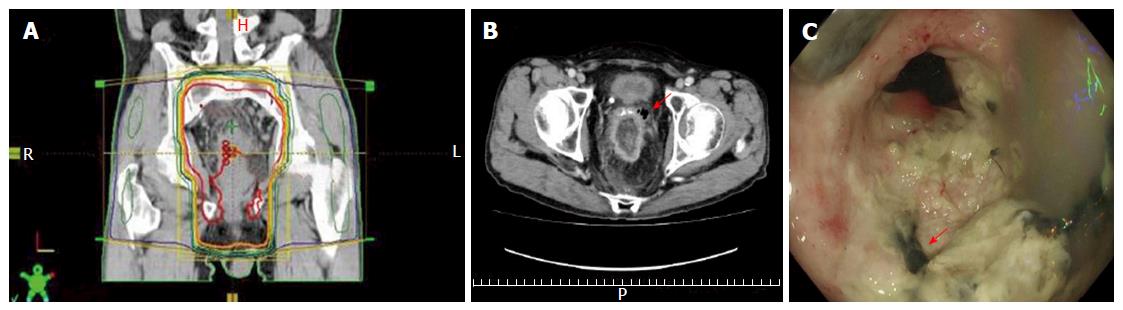

The patient was scheduled for preoperative 5-FU-based CRT. Administration of a fixed dose of tegafur/uracil (UFT) (300 mg/body per day) and leucovorin (LV) (75 mg/body per day) was planned for days 1-28. Concurrent RT administration to the whole pelvis (Figure 2A) was planned in fractions of 1.8 Gy/d, 5 d a week for 5 wk (45 Gy in 25 fractions). However, the patient developed a typical fever at 25 d after starting CRT (36 Gy in 20 fractions received). The CT findings revealed rectal perforation with air-fluid around the left side of the seminal vesicle adjacent to the rectum (Figure 2B), and the colonoscopic examination also showed the perforation of the tumor wall (Figure 2C). The patient underwent construction of a sigmoid colostomy as an emergency surgery.

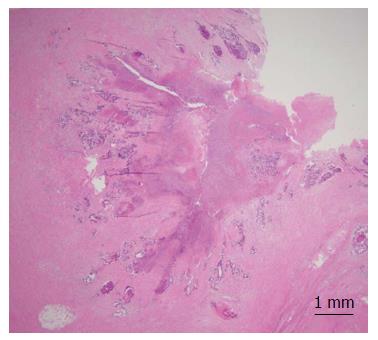

At 12 d after the surgery with no inflammatory findings, the remaining CRT was commenced, and was completed safely according to plan. The patient underwent abdominoperineal resection of the rectum including the prostate and seminal vesicle with a laparoscopic technique as minimally invasive surgery. The histopathological findings revealed that a wide area of tumor tissue had been replaced by necrotic tissue and fibrous tissue, suggesting that chemoradiation had been effective (Figure 3). The Union for International Cancer Control (UICC) TNM staging[5] of the tumor was pT3, N0 (0/34), M0. No evident disease recurrence has been observed in the patients for 8 mo.

RT is one of the useful modalities for various cancers including rectal cancer. Currently, more than 50% of cancer patients receive RT with or without chemotherapy[6]. RT gives rise to various cellular responses including both DNA and membrane damage[7]. The DNA damage leads to cell cycle arrest, apoptosis, stress and the activation of DNA repair processes through coordinating intracellular signal pathways involving poly ADP ribose polymerase, ERK1/2, p53 and ataxia telangiectasia mutated[7,8]. Concerning pelvic RT with concurrent 5-FU-based chemotherapy, 5-FU can increase radiation sensitivity[3,9]. However, RT causes various side effects that damage healthy cells and tissues near the treatment area.

Radiation-related tissue injuries are well known to occur in the gastrointestinal tract. Acute radiation-related small bowel toxicity often occurs during RT for LARC. The overall incidence of acute Grade 3-4 diarrhea was 16%-39% in prospective studies of preoperative RT[10]. Concerning the rectum, radiation proctitis is generally classified as acute or chronic phase by the timeframe of the symptoms, and chronic proctitis may include acute proctitis defined as an inflammatory process. However, the detailed pathogenesis of RT-induced proctitis is not yet clear. Acute proctitis including symptoms of diarrhea, nausea, cramps, tenesmus, urgency, mucus discharge and minor bleeding occurs within 6 wk after the start of RT[11]. Severe bleeding, strictures, perforation, fistula and bowel obstruction occur in the chronic phase, which may not become apparent for months to years[12]. Concerning pelvic RT with concurrent 5-FU-based chemotherapy, severe acute small-bowel toxicity was found to be associated with radiation in a dose-dependent manner[13,14].

Colorectal perforation is a life-threatening complication. The causes of rectal perforation include fecal impaction, enema, and cancer and its therapy, including RT, chemotherapy and molecular-targeted therapy. Among them, rectal perforation from pelvic RT is an extremely rare adverse event. The mechanisms of radiation-related perforation, especially the difference in responses between normal rectal tissue and LARC tissue, remain elusive. RT-induced normal tissue perforation is generally caused by accumulation of radiation-induced irreversible ischemic mechanisms with submucosal fibrosis and obliteration of small blood vessels[15]. In addition to the ischemic change, cancer tissue with high radiation sensitivity results in massive necrotic death, which in turn triggers an inflammatory reaction analogous to a wound-healing response[15-17].

There is general agreement that radiation-induced gastrointestinal injuries are associated with the dose of radiation. Late normal tissue reactions are more dependent on the dose per fraction than acute reactions[18]. Still, Do et al[12] reported that a total dose of 45 to 50 Gy delivered to the pelvis for adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment for rectal malignancies generally causes very few acute and late morbidities.

However, total treatments of > 70 Gy cause significant and long-standing injury to the surrounding area[12,19]. In the present case, the main cause of the standard 5-FU-based CRT-related rectal perforation was thought to be not direct radiation morbidity but a secondary effect of the tumor necrosis. In addition to excessive treatment effects of CRT, the potential risks for CRT-related LARC perforation may include the presence of diverticula, collagenosis and tumor ulceration. Khan et al[20] also argue that the biological behavior of the tumor may have a large influence on whether an event occurs because all transrectal tumors have the potential for perforation. Pathological and immunohistochemical analyses of various factors in colorectal tumor perforation compared with non-perforated tumor showed significant associations of tumor location and cell differentiation[21].

We searched all common literature search engines (PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar). To our knowledge, only 6 cases of perforated LARC associated with 5-FU-based preoperative CRT have been reported[20,22,23] (Table 1). Among them, the cases of perforation in the midst of preoperative CRT were only 2 in number. Furthermore, completion of preoperative CRT according to the original plan after supporting emergency recovery for CRT-related rectal perforation has never before been described.

| Case | Ref. | Sex | Time to perforation | Surgical intervention (additional surgery) | TNM | Outcome |

| Age | Total dose of RT (Gy/fr) | Classification1 | ||||

| 1 | Lee et al[22] | F | 5 D after planned CRT | LAR | cT4, NX, MX | Alive |

| 67 | 50 Gy/28 fr | pT4, N2, M0 | ||||

| 2 | Lee et al[22] | F | Immediately after planned CRT | Ileostomy | cT4, NX, MX | Alive |

| 78 | 54 Gy/unknown | |||||

| 3 | Lee et al[22] | M | 2 W in the middle of planned CRT | Colostomy | cT3, NX, MX | Perioperative death |

| 72 | 21.6 Gy/unknown | |||||

| 4 | Lee et al[22] | M | 4 W in the middle of planned CRT | Colectomy with ileostomy | cT3, NX, MX | Perioperative death |

| 76 | 36 Gy/unknown | |||||

| 5 | Khan et al[20] | M | 1 W after planned CRT | LAR | cT3, N1, M0 | Alive |

| 47 | 50.45 Gy/28 fr | pT3, N2, M0 | ||||

| 6 | ElGendy et al[23] | F | 2 W after planned CRT | LAR | cT3, N1, M0 | Alive |

| 55 | 45 Gy/unknown | pT3, N2, M0 | ||||

| 7 | Our case | M | 25 D in the middle of planned CRT | Colectomy (APR after remaining planned CRT) | cT4, N2, M0 | Alive |

| 56 | 36 Gy/20 fr | pT3, N0, M0 |

In recent years, various molecularly targeted agents have been used clinically for colorectal cancer. However, the spread of molecularly targeted therapies including combination RT has resulted in more cases of agent-induced gastrointestinal perforation[24,25]. Gastrointestinal perforation has occurred in both non-tumor tissue and tumor tissue including rectal cancer[26]. To avoid severe complications related to CRT, such as LARC perforation, regimens of chemotherapy as well as methods of radiation therapy should be carefully considered.

In conclusion, we documented an extremely rare case of LARC that developed preoperative rectal perforation in the midst of 5-FU-based preoperative CRT. We share this case as important evidence for the treatment for LARC perforation in the midst of preoperative CRT. Our case findings imply that completing preoperative CRT after supporting emergency recovery may enhance the anti-tumor effect, resulting in a better prognosis for such cases.

A 56-year-old male with locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) developed preoperative rectal perforation in the midst of 5-fluorouracil (FU)-based preoperative chemoradiotherapy (CRT).

Colonoscopy and imaging tests resulted in a clinical diagnosis of LARC with direct invasion to adjacent organs and regional lymphadenopathy.

Inflammatory associated rectal perforation.

Preoperative serum level of carcino embryonic antigen was increased to 21.0 ng/mL (normal < 2.5).

The computed tomography findings revealed rectal perforation with air-fluid around the left side of the seminal vesicle adjacent to the rectum.

A wide area of tumor tissue was replaced by necrotic tissue and fibrous tissue, suggesting that chemoradiation had been effective.

The patient completed preoperative CRT after supporting emergency recovery.

To our knowledge, only 6 cases of perforated LARC associated with 5-FU-based preoperative CRT have been reported.

The authors share this case as important evidence for the treatment of LARC perforation in the midst of preoperative CRT.

This case report demonstrated that completing preoperative CRT after supporting emergency recovery may enhance the anti-tumor effect, resulting in a better prognosis.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Rasmussen SL, Trevisani L S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Sauer R, Liersch T, Merkel S, Fietkau R, Hohenberger W, Hess C, Becker H, Raab HR, Villanueva MT, Witzigmann H. Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1926-1933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1251] [Cited by in RCA: 1489] [Article Influence: 114.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Roh MS, Colangelo LH, O’Connell MJ, Yothers G, Deutsch M, Allegra CJ, Kahlenberg MS, Baez-Diaz L, Ursiny CS, Petrelli NJ. Preoperative multimodality therapy improves disease-free survival in patients with carcinoma of the rectum: NSABP R-03. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5124-5130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 703] [Article Influence: 43.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | De Caluwé L, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Ceelen WP. Preoperative chemoradiation versus radiation alone for stage II and III resectable rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD006041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tomono A, Yamashita K, Kanemitsu K, Sumi Y, Yamamoto M, Kanaji S, Imanishi T, Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Tanaka K. Prognostic significance of pathological response to preoperative chemoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sobin LH, Gospodarowicz MK, Wittekind C. TNM classification of malignant tumours, 7th edn. Wiley-Blackwell, Oxford. 2009;. |

| 6. | Bentzen SM. Preventing or reducing late side effects of radiation therapy: radiobiology meets molecular pathology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:702-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 710] [Cited by in RCA: 725] [Article Influence: 38.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Watters D. Molecular mechanisms of ionizing radiation-induced apoptosis. Immunol Cell Biol. 1999;77:263-271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiao M, Whitnall MH. Pharmacological countermeasures for the acute radiation syndrome. Curr Mol Pharmacol. 2009;2:122-133. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kvols LK. Radiation sensitizers: a selective review of molecules targeting DNA and non-DNA targets. J Nucl Med. 2005;46 Suppl 1:187S-190S. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Grann A, Minsky BD, Cohen AM, Saltz L, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Kelsen DP, Kemeny N, Ilson D, Bass-Loeb J. Preliminary results of preoperative 5-fluorouracil, low-dose leucovorin, and concurrent radiation therapy for clinically resectable T3 rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1997;40:515-522. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Williams G, Yan BM. Endoscopic ultrasonographic features of subacute radiation proctitis. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:1495-1498. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Do NL, Nagle D, Poylin VY. Radiation proctitis: current strategies in management. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2011;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Baglan KL, Frazier RC, Yan D, Huang RR, Martinez AA, Robertson JM. The dose-volume relationship of acute small bowel toxicity from concurrent 5-FU-based chemotherapy and radiation therapy for rectal cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:176-183. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Minsky BD, Conti JA, Huang Y, Knopf K. Relationship of acute gastrointestinal toxicity and the volume of irradiated small bowel in patients receiving combined modality therapy for rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:1409-1416. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Clarke RE, Tenorio LM, Hussey JR, Toklu AS, Cone DL, Hinojosa JG, Desai SP, Dominguez Parra L, Rodrigues SD, Long RJ. Hyperbaric oxygen treatment of chronic refractory radiation proctitis: a randomized and controlled double-blind crossover trial with long-term follow-up. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;72:134-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140:883-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8437] [Cited by in RCA: 8181] [Article Influence: 545.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wei-Xing Z, Craig BT. Necrotic death as a cell fate. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1-15. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 682] [Cited by in RCA: 631] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Di Staso M, Bonfili P, Gravina GL, Di Genesio Pagliuca M, Franzese P, Buonopane S, Osti MF, Valeriani M, Festuccia C, Enrici RM. Late morbidity and oncological outcome after radical hypofractionated radiotherapy in men with prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2010;106:1458-1462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coia LR, Myerson RJ, Tepper JE. Late effects of radiation therapy on the gastrointestinal tract. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:1213-1236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 317] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Khan A, Suhaibani YA, Sharief AA. Rectal cancer perforation: a rare complication of neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;7:1-5. |

| 21. | Medina-Arana V, Martínez-Riera A, Delgado-Plasencia L, Rodríguez-González D, Bravo-Gutiérrez A, Álvarez-Argüelles H, Alarcó-Hernández A, Salido-Ruiz E, Fernández-Peralta AM, González-Aguilera JJ. Clinicopathological analysis of factors related to colorectal tumor perforation: influence of angiogenesis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee J, Chen F, Steel M, Keck J, Mackay J. Perforated rectal cancer associated with neoadjuvant radiotherapy: report of four cases. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1629-1632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | ElGendy K. Rectal perforation after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for low-lying rectal cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Takada S, Hoshino Y, Ito H, Masugi Y, Terauchi T, Endo K, Kimata M, Furukawa J, Shinozaki H, Kobayashi K. Extensive bowel necrosis related to bevacizumab in metastatic rectal cancer patient: a case report and review of literature. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2015;45:286-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Samantha LK, Allison FL, Patrick GJ, Pedro ADB, Michael BA. Bowel perforation associated with robust response to BRAF/MEK inhibitor therapy for BRAF-mutant melanoma: a case report. Melanoma Management. 2015;2:115-120. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Borzomati D, Nappo G, Valeri S, Vincenzi B, Ripetti V, Coppola R. Infusion of bevacizumab increases the risk of intestinal perforation: results on a series of 143 patients consecutively treated. Updates Surg. 2013;65:121-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |