Published online Jan 16, 2017. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v5.i1.14

Peer-review started: August 16, 2016

First decision: September 28, 2016

Revised: October 2, 2016

Accepted: November 1, 2016

Article in press: November 2, 2016

Published online: January 16, 2017

Processing time: 147 Days and 10.5 Hours

Intra-abdominal abscess and an intractable abdominal wall sinus forty years after splenectomy is rare, which has not been described previously in the surgical literature. We report the management of a patient who had presented with an intractable sinus on his left hypochondrium forty years after having undergone splenectomy and cholecystectomy, which persisted for more than two years despite repeated surgery and courses of antibiotics and compromised quality of life significantly from pain. A sinogram and computerised tomographic scan followed by exploration and laying open of the sinus delivered multiple silk sutures used for ligation of splenic pedicle, led to complete resolution of the sinus. It is important to avoid using non-absorbable silk sutures during splenectomy when splenectomy is undertaken in a contaminated field. Appropriate imaging and exploration is mandatory for its resolution.

Core tip: An intra-abdominal abscess and a sinus 40 years following splenectomy is rare, which should be investigated with a computerised tomographic scan and a sinogram and treated by exploration. Non-absorbable silk sutures, which act as nidus for bacteria, should be avoided if splenectomy is undertaken simultaneously with surgery on a hollow viscus.

- Citation: Shrestha B, Hampton J. Intra-abdominal abscess and intractable sinus - a rare late complication after splenectomy. World J Clin Cases 2017; 5(1): 14-17

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v5/i1/14.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v5.i1.14

Splenectomy is performed for a wide range of medical conditions such as haematological disorders, portal hypertension and trauma, which can be attended by complications, principally infectious and thromboembolic[1]. Splenectomy is also performed in association with surgery of other abdominal viscera, particularly in multiply injured trauma victims, where contamination of abdominal cavity is present[2]. Chronic intra-abdominal sepsis can compromise the quality of life significantly and be challenging from diagnostic and treatment perspectives. We describe the management challenges posed by the late presentation of a patient with intra-abdominal abscess followed by an intractable abdominal wall sinus 40 years after splenectomy and review pertinent literature.

A 62-year-old male was referred to our general surgical clinic from the dermatology department for a second opinion and management of a persistently discharging sinus on the left hypochondrium of two years duration, which was associated with severe eczematous changes on the skin around the sinus, unresponsive to topical steroid creams. He experienced continuous pain in the left upper abdomen, which compromised his sleep and work, and was on regular diazepam 5 mg nocte, morphine sulphate solution 5-10 mg PRN, sustained-release morphine sulphate (Zomorph®) 10 mg 12 hourly and oral phenoxymethylpenicilln 250 mg twice daily.

Aged 19, he had undergone a cholecystectomy and splenectomy for gallstones and portal hypertension through an upper midline incision. Forty years after the surgery, he presented with a painful lump on his left hypochondrium with clinical features suggestive of an intra-abdominal abscess. The abscess, containing thick pus, was drained through a transverse subcostal incision. Although the operation record described that the omentum was herniating through a 1 cm diameter defect in the muscles, which was closed with interrupted 0 prolene sutures; in retrospect, the omentum was walling off the abscess, which was mistaken for an incisional hernia. After four weeks, a discharging sinus developed through the middle of the scar, which refused to heal despite debridement on three occasions, regular dressings and courses of flucloxacilln. Over the following two years, the pain and the sinus persisted and caused severe disability. Due to the extensive excoriation of the skin surrounding the sinus, he was referred to a dermatology clinic.

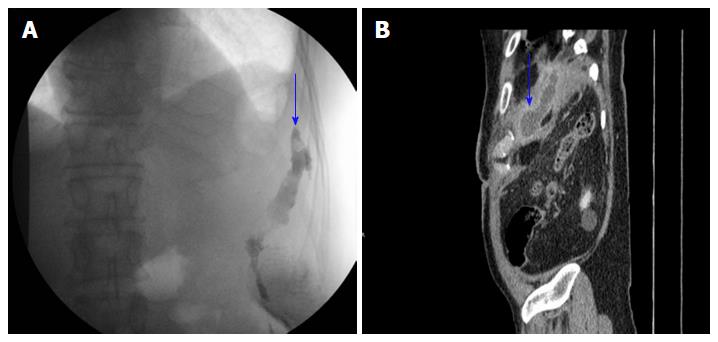

On examination, the skin around the sinus showed severe eczematous changes and the sinus was adherent to the left costal margin in the mid-axillary line the white blood cell count was 16 × 109/L and the C-reactive protein was 21 units/mL culture of the pus grew Staphylococcus aureus sensitive to flucloxacilln. A plain computerised tomographic (CT) scan showed a septated extraperitoneal collection in the left upper abdomen measuring 85 mm × 25 mm × 20 mm with adjacent inflammatory changes (Figure 1A). A sinogram delineated the tract under the ribs towards the upper quadrant. There was no communication with the bowel. A CT scan of the abdomen, following the sinogram, after the administration of oral water and intravenous contrast, showed the contrast in the cavity (5 cm × 15 cm in maximum axial dimensions) lying in the extraperitoneal space, which extended from the opening under lower edge of the rib cage to the under surface of the diaphragm cranially. The splenic flexure and the descending colon lay close to the cavity without communication between them (Figure 1B).

The sinus was explored under general anaesthesia. Using a 6 Fr feeding tube, methylene blue dye was injected into the cavity. Through a generous subcostal incision, the sinus tract was followed cranially keeping the dissection close to the rib cage and laid it fully open. The cavity contained thick pus and free-floating braided black silk sutures (15 in number), it was thoroughly curetted with a Volkmann’s spoon and washed with copious amount of saline and hydrogen peroxide solution. The wound was closed in layers after inserting a 16 Fr Robinson’s drain, which was removed after 7 d and the patient was discharged home. The specimens from the sinus contained multiple pieces of fibrous tissue, largest measuring 20 mm in maximum dimension. The histology of the sinus tract showed chronically inflamed fibrous tissue with no evidence of granulomatous inflammation or neoplastic disease. On a routine follow-up after three weeks, the wound has healed with no sign of recurrence of the sinus. The patient has stopped taking analgesia or tranquillizers. On a telephone enquiry two years following the surgery, he remained well, pain free and not on any drugs, with no signs of recurrence of sinus.

The spleen is crucial in regulating immune homoeostasis through its ability to link innate and adaptive immunity and in protecting against infections[3]. Asplenic patients have a lifelong risk of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection and have been reported to have low numbers of peripheral blood IgM memory B cells[4]. Immunisation and prophylactic antibiotics help preventing post-splenectomy opportunistic infections.

Presentation with an intra-abdominal abscess and a non-healing sinus, 40 years following splenectomy, is rare and unreported in the surgical literature. Surgical treatment of acute cholecystitis or appendicitis, is known to be associated with a higher risk of late abscess formation, due to retained stones in the abdominal cavity/wall or contamination of the wound at the time of surgery, respectively[5,6]. The differential diagnosis of a non-healing sinus includes tuberculosis, malignancy, presence of foreign bodies and communication with abdominal organs to the skin surface. Moreover, mesh repair of an incisional or inguinal hernia, as well as the use of silk yarn in surgical sutures, are associated with late abscess formation. The silk acts as a foreign body and a nidus for latent infection, which can manifest with sinuses several years after the primary surgery as in our case[7].

Intra-abdominal abscesses can also occur due to injury to the stomach, pancreas or intestine during splenectomy, but the incidence reported is less than 1 percent and the presentation is usually early during the post-operative period[8,9]. Splenectomy performed for splenic abscess can present with intra-abdominal abscess due to contamination of peritoneal cavity and post-splenectomy immunosuppressed state[10]. Bacterial translocation is the invasion of indigenous intestinal bacteria through the gut mucosa to normally sterile tissues and internal organs, which could lead to delayed infection as in our case[11].

Our patient had undergone a splenectomy with ligation of the splenic vessels with silk sutures and a cholecystectomy in the same sitting. It is highly likely that contamination of the splenic bed containing silk sutures with the organisms present in the gall bladder had led to this delayed presentation with a splenic bed abscess and persistent sinus. Resolution of the sinus after removal of the infected silk sutures, emphasises the need for avoidance of using braided silk sutures during surgery, particularly, when splenectomy is performed together with resection of hollow abdominal viscera or when an immunosuppressed state is likely to follow, such as after splenectomy and organ transplantation. Utilisation of absorbable and non-braided sutures can potentially prevent this complication. Polyglactin 910 is considered to be the optimum suture in preventing the formation of adhesions and abscesses[12]. A sinogram and CT scan followed by early exploration, removal of the sutures and complete excision of the sinus tract through adequate surgical access are essential for a permanent cure and amelioration of prolonged suffering of the patient.

A 62-year-old man with history of undergoing splenectomy 40 years ago presented with presented with a 2-year history of a sinus following drainage of an intra-abdominal abscess, which refused to heal despite repeated surgical interventions.

A discharging sinus on the left hypochondrium with excoriation of skin.

A chronic sinus due to tuberculosis, malignancy, presence of foreign body or a fistula communicating to intra-abdominal organs.

There was leucocytosis and raised C-reactive protein. Staphylococcus aureus was isolated from the discharge emanating from the sinus.

A plain computerised tomographic (CT) scan showed a septated extraperitoneal collection in the left upper abdomen measuring 85 mm × 25 mm × 20 mm with adjacent inflammatory change. A sinogram delineated the tract under the ribs towards the upper quadrant. There was no communication with the bowel.

The histology of the sinus tract showed chronically inflamed fibrous tissue with no evidence of granulomatous inflammation or neoplastic disease.

Exploration of the sinus, removal of retained silk sutures and curettage of the sinus led to complete healing.

Intra-abdominal abscess and infections following use of non-absorbable sutures have been reported in the past. But a case like this presenting 40 years after having undergone splenectomy has not been reported in the past.

The case emphasizes the need for appropriate investigations with a sinogram and CT imaging followed by early exploration of the sinus. Use of non-absorbable sutures should be avoided to prevent such complications.

This is a very rare case indeed. The case report is correctly structured, well written, the case is well and completely described. It is indeed useful as a case report for clinical practice.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Elpek GO, Surlin VM S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Li D

| 1. | Buzelé R, Barbier L, Sauvanet A, Fantin B. Medical complications following splenectomy. J Visc Surg. 2016;153:277-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Weledji EP. Benefits and risks of splenectomy. Int J Surg. 2014;12:113-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Di Sabatino A, Carsetti R, Corazza GR. Post-splenectomy and hyposplenic states. Lancet. 2011;378:86-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 412] [Cited by in RCA: 438] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cameron PU, Jones P, Gorniak M, Dunster K, Paul E, Lewin S, Woolley I, Spelman D. Splenectomy associated changes in IgM memory B cells in an adult spleen registry cohort. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Rossem CC, Bolmers MD, Schreinemacher MH, van Geloven AA, Bemelman WA. Prospective nationwide outcome audit of surgery for suspected acute appendicitis. Br J Surg. 2016;103:144-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sista F, Schietroma M, Santis GD, Mattei A, Cecilia EM, Piccione F, Leardi S, Carlei F, Amicucci G. Systemic inflammation and immune response after laparotomy vs laparoscopy in patients with acute cholecystitis, complicated by peritonitis. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;5:73-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Calkins CM, St Peter SD, Balcom A, Murphy PJ. Late abscess formation following indirect hernia repair utilizing silk suture. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O’Sullivan ST, Reardon CM, O’Donnell JA, Kirwan WO, Brady MP. “How safe is splenectomy?”. Ir J Med Sci. 1994;163:374-378. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Barmparas G, Lamb AW, Lee D, Nguyen B, Eng J, Bloom MB, Ley EJ. Postoperative infection risk after splenectomy: A prospective cohort study. Int J Surg. 2015;17:10-14. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Han SP, Galketiya K, Fisher D. Primary splenic abscess requiring splenectomy. ANZ J Surg. 2016;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lima Kde M, Negro-Dellacqua M, Dos Santos VE, de Castro CM. Post-splenectomy infections in chronic schistosomiasis as a consequence of bacterial translocation. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2015;48:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ishikawa K, Sadahiro S, Tanaka Y, Suzuki T, Kamijo A, Tazume S. Optimal sutures for use in the abdomen: an evaluation based on the formation of adhesions and abscesses. Surg Today. 2013;43:412-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |