Published online Sep 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i9.273

Peer-review started: April 24, 2016

First decision: June 6, 2016

Revised: June 8, 2016

Accepted: July 11, 2016

Article in press: July 13, 2016

Published online: September 16, 2016

Processing time: 137 Days and 14.2 Hours

Intestinal tuberculosis (TB) is an uncommon lesion for which differential diagnosis can be difficult. We present a case of a 53-year-old male and a systematic review of the literature, from clinical symptoms to differential diagnosis, unusual complications and therapy. The patient was admitted to the hospital with signs of acute abdomen as a result of a perforated terminal ileitis. Based on the skip lesions of the terminal ileum and cecum, Crohn’s disease (CD) was clinically suspected. An emergency laparotomy and right colectomy with terminal ileum resection was performed and systematic antibiotherapy was prescribed. The patient’s status deteriorated and he died 4 d after the surgical intervention. At the autopsy, TB ileotyphlitis was discovered. The clinical criteria of the differential diagnosis between intestinal TB and CD are not very well established. Despite the large amount of published articles on this subject, only 50 papers present new data regarding intestinal TB. Based on these studies and our experience, we present an update focused on the differential diagnosis and therapy of intestinal TB. We highlight the importance of considering intestinal TB as a differential diagnosis for inflammatory bowel disease. Despite the modern techniques of diagnosis and therapy, the fulminant evolution of TB can still lead to a patient’s death.

Core tip: In this paper, we performed a case-based update of data regarding intestinal tuberculosis. In the case the patient was hospitalized with suspicion of Crohn’s disease and ileal perforation but the autopsy revealed a tuberculous ileotyphlitis. The necessity of a complete differential diagnosis and not forgotten the tuberculosis as a potential cause of death was highlighted in the paper.

- Citation: Gurzu S, Molnar C, Contac AO, Fetyko A, Jung I. Tuberculosis terminal ileitis: A forgotten entity mimicking Crohn’s disease. World J Clinical Cases 2016; 4(9): 273-280

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i9/273.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i9.273

Intestinal tuberculosis (TB) is a very rare disease of the twenty-first century that has almost been forgotten in the daily practice of medicine, although the incidence of abdominal TB has increased over the past two decades, especially in the United Kingdom, Asia and other tropical regions[1-3]. About 36%-90% of all cases of abdominal TB involve the ileocecal junction and/or jejunoileum (due to the high density of lymphoid aggregates and physiologic stasis in these segments), followed by peritoneal involvement (33%)[1,4]. In contrast, the number of reports related to the non-tuberculous inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), especially ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease (CD), is increasing and new drugs are being discovered for their therapy.

In this paper, we present a life-threatening case of TB ileotyphlitis that was clinically misdiagnosed as CD. A review of data from the literature regarding the incidence of TB ileotyphlitis and criteria for differential diagnosis of this lesion are also synthesized in the discussion.

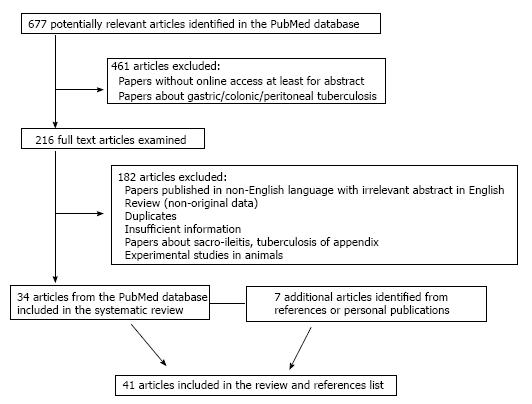

Using the term “tuberculous ileotyphlitis”, only four papers were identified in the PubMed database, being published in the years 1957[5,6], 1982[7] and 1999[8]. Using the term “tuberculous ileitis”, another 68 were identified but only seven were representative and they were included in the present systematic review[1,2,9-13]. Using the term “ileal tuberculosis” and “ileocecal tuberculosis” another 605 papers were identified, only 27 of which provided supplementary data. The date of the last search was March 21, 2016. After careful revision, the 34 selected papers were used for the systematic review of the literature that is presented in the discussion, adding another nine new references[14-41] (Figure 1).

A 53-year-old healthy Romanian male, without prior medical disorders, was admitted to the hospital complaining of diffuse abdominal pain for the two weeks previous to admission and subfertility. No changes in bowel habits, weight loss or gastrointestinal bleeding were declared. No chronic use of medications such non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) or antihypertensive substances were noted.

At the time of admission, severe abdominal pain and signs of acute abdomen, with tenderness and guarding of the abdominal wall and no intestinal sounds was found. The computed tomography (CT)-scan of the abdominal cavity indicated suspicion of peritonitis as result of perforation of the terminal ileum. Multiple skip lesions were also described in the terminal ileum and cecum. An emergency laparotomy was performed. Blood analysis showed anemia [Hemoglobin 9.6 g/dL (normal values 12-17 g/dL), hematocrit 29.8% (normal values 36%-54%)], thrombocytopenia [platelets 87000/μL (normal values 150000-450000/μL)] and leukocytosis [total leukocytes: 16 × 109/L (normal values 3.6-10 × 109/L)].

The intraoperative exploration of the abdominal cavity revealed skip perforations of the terminal ileum and diffuse peritonitis with fibrin membranes that mimicked a CD. A right hemicolectomy with a terminal ileum resection was performed. The other gastrointestinal segments did not show modifications. The postoperative status of the patient deteriorated and, despite undergoing antibiotherapy, the patient died four days after surgery. The clinical diagnosis was septic shock and bilateral bronchopneumonia.

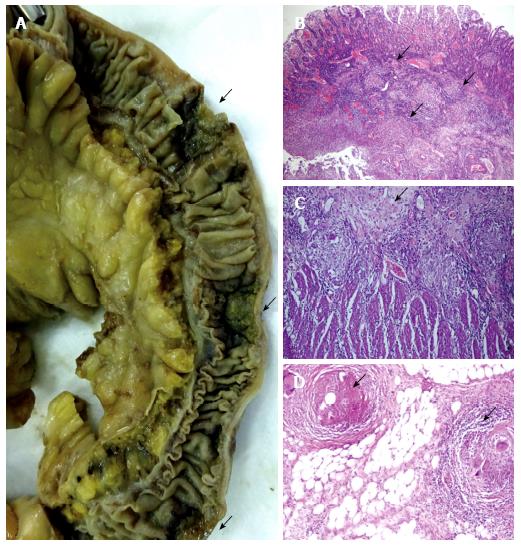

Gross examination of the surgical specimen revealed in the terminal ileum and cecum multiple skip transverse ulcerations 1-2 cm in length with strictures and multiple perforations (Figure 2).

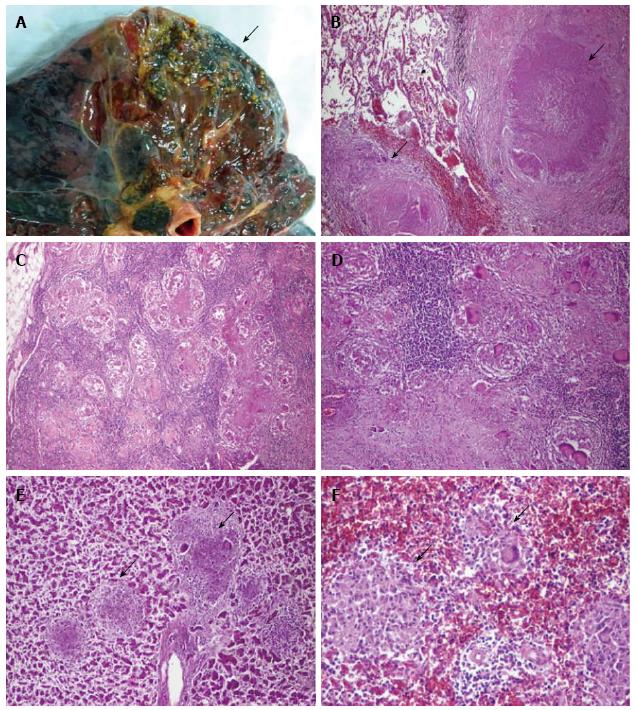

At autopsy, diffuse peritonitis was confirmed. The rest of the gastrointestinal tract presented no modifications. In the lungs, in the upper lobes, multiple small yellowish nodules were found bilaterally (Figure 3). A few nodules were also found in the liver and spleen. No lesions of the kidney, adrenal glands or bone were detected.

Histopathological examination of the surgical specimen revealed tuberculous granulomas in both terminal ileum and cecum. These granulomas presented minimal central caseous necrosis surrounded by epithelioid cells and a few Langhans giant cells. Granulomas were also found in the mesenteric lymph nodes, lung parenchyma, liver and spleen (Figure 3).

Based on the macroscopically and microscopically derived findings, the final diagnosis was “Miliary TB of the lung, liver and spleen, with transmural tuberculous ileotyphlitis”. The death was established as a result of peritonitis-related septic shock.

Despite the improvements in diagnosis and therapy, no specific guidelines have been elaborated for the diagnosis and therapy of symptomatic terminal ileitis[1,9]. In patients with isolated terminal ileitis or ileotyphlitis, the differential diagnosis should include CD, TB (Mycobacterium tuberculosis or bovis), sarcoidosis, non-specific IBD (e.g., Yersinia and Salmonella infections for ileitis and amebiasis, and Clostridium infection for ileocolonic ulcers, ischemia, eosinophilic enteritis and amyloidosis), drug-induced ileitis (e.g., NSAIDS, parenteral gold therapy, oral contraceptives, ergotamine, digoxin, diuretics, antihypertensives, potassium chloride, etc.), radiation ileitis, other granulomatous inflammations (arteritis, spondyloarthropathies, actinomycosis, infection with Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium paratuberculosis or cytomegalovirus), endometriosis, backwash ileitis in patients with ulcerative colitis, enteric fever, diverticula including Meckel’s diverticulum, ileal or colonic angiodysplasia, Behçet’s disease, tumors, typhoid fever and foreign-body granulomas determined by the non-absorbable suture materials[1,2,4,9-11,14,22,23,25,30,35]. In some cases, two of these lesion types can be found together. A case of miliary TB with intestinal involvement was recently reported in a patient with Behçet’s disease[25]. Coexisting intestinal and pulmonary TB should also be explored to sustain the diagnosis[38].

For a proper differential diagnosis, geographical differences must be taken into account. TB is more frequent in tropical countries when compared with Western regions and Saudi Arabia (Table 1)[1,2,12,16,23,38,39]. In China, there is an increasing incidence of intestinal TB in parallel with a three-fold increase in the incidence of CD, which was reported in the last two decades[38,39].

| Parameter | Tuberculosis | Crohn’s disease |

| Geographic predominance | Asia, India, Pakistan | Western regions, Saudi Arabia |

| Symptoms | ||

| Duration of symptoms | Short (about 7 mo) | Long (about 58 mo) |

| Abdominal pain | 18%-90% | 18%-90% |

| Acute abdomen | 67% | Rare |

| Weight loss | 55%-80% | 55%-80% |

| Anorexia | 45% | Frequent |

| Hematochezia | 4%-18% | 31% |

| Diarrhea | 35%-55% | 69% (bloody diarrhea) |

| Diarrhea alternating with constipation | 38% | Rare |

| Ascites | Frequent | Rare |

| Anemia | 45%-64% | Frequent |

| Fever | 55%-69% | 23%-45% |

| Night sweats | 31% | Rare |

| Intra-abdominal abscesses | Frequent | Frequent (fistula) |

| Perianal disease | Rare | Frequent (25%-50%) |

| Extra-intestinal disorders | Pulmonary tuberculosis (60%), neuropathies (vitamin B12 deficiency) | pyoderma gangrenosum, uveitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, aphthous stomatitis, arthritis, etc. |

| CT-scan | Thickening of the ileocecal valve and of the medial wall of the cecum and a retracted, conical, and shrunken cecum | Minimal and uniform intestinal wall thickening, mural stratification, vascular jejunization or the comb sign, mesenteric fibrofatty proliferation and skip lesions |

| Colonoscopy | Transverse and rodent-like ulcers with a patulous ileocecal valve | Longitudinal ulcers and a comb sign |

| Therapy | ||

| Medications | Anti-TB agents (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, streptomycin, ethambutol, etc.) | Steroids anti-tumor-necrosis-factor agents (infliximab) |

| Surgery | Laparoscopic-assisted ileocolectomies | Usually open surgery |

The symptoms are relatively similar in both CD and TB and mainly refer to diffuse abdominal-, right iliac fossa- or periumbilical-pain. However, the duration of symptoms (longer in CD and shorter in TB), some particular features, and the associated extra-intestinal disorders may be indicators for a presumptive diagnosis (Table 1)[1,2,4,9,12,14,19,23,25,36,38]. Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhages are more frequent in CD than intestinal TB and the small bowel is the main source of hemorrhage in one third of patients suffering from rectal bleeding (hematochezia)[1,2,4,9,12,14,19,23,25,36,38]. However, intestinal hemorrhages can also occur in patients with other IBD types, vascular malformations, aorto-enteric fistula, and tumors[13].

In children with ileal TB, the abdominal mass can be palpated in the right-lower quadrant (67%) and weight loss, malnutrition, abdominal colic, changes of the bowel habits and vomiting are associated symptoms[17,20,25,36]. In patients with CD and vasculitis, the extra-intestinal symptoms (Table 1) are associated in 61% of the cases, whereas drug-induced ileitis and spondyloarthropathies are mostly asymptomatic[4,12].

During the colonoscopy and macroscopic examination, both CD and TB showed similar features. They are characterized by isolated ulcerations (deep or superficial, skip or continuous), hypertrophic/nodular, ulcero-constrictive/ulcero-hypertrophic lesions or fibrous strictures[4,9,18,38]. The ileal TB, in most of the cases, is an transverse ulcerative lesion (53%), followed by ulcero-proliferative (27%) and proliferative (20%) features[38,39]. The longitudinal ulcers rather indicate CD (Table 1)[39]. In a few cases, the colonoscopy is normal[1]. Due to an increased incidence of ileitis and to avoid misdiagnoses, routine terminal ileoscopies and biopsies are suggested in symptomatic patients with suspected IBD, as a part of colonoscopy[2,23]. Performing a terminal ileoscopy takes three minutes without having any associated complications[2]. Moreover, from all unselected patients who undergo colonoscopies, 2%-10% present macroscopic or microscopic abnormalities of the terminal ileum and most of them have Crohn’s ileitis[2]. For those with normal macroscopic aspects, 3%-14% of them present microscopic changes[1,2].

Microbiological cultures lack a high specificity and/or sensitivity for Mycobacterium tuberculosis or acid-fast bacilli because they are positive only in 71% of the cases[1]. TB-PCR seems to be specific for TB but low sensitivity was reported[2,12,30]. Raised values of serum inflammatory markers do not contribute information about the IBD type[2]. The anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies are considered specific to CD but can also be high in TB cases[12]. The newest laboratory tests considered to be diagnostic tools for differentiating TB from CD are the serum-based T-SPOT[39] and the immunohistochemical antibodies against Mycobacterium tuberculosis[40].

Although most cases of TB ileitis (70%) are the result of the ingestion of infected sputum from an active pulmonary TB, and are rarer as a result of systemic spreading, the chest radiography result is normal in 70% of the cases[4]. The histological assessment helps to establish the diagnosis in 66%-86% of the cases[4,23,38]. A barium examination shows shallow ulcers, thickened folds and spasticity[18]. The CT-scan can also be used for the differential diagnosis between intestinal TB and CD (Table 1)[18,39]. In the present case, TB-related skip lesions increased the difficulty of the diagnosis. In the literature, skip ulcers were reported in 14% of patients with intestinal TB[23].

The main complications of ileal TB are: Massive hematochezia (that can be controlled by endoscopic coagulation therapy), bowel obstruction (14%-32% of the cases), necrosis and intestinal perforation (1%-15%), enterocutaneous fistula (2%), ileoileal fistula, mesenteric lymphadenitis with intussusception, ileal loops or intestinal volvulus (2%), ascites, purulent or stercoral peritonitis (1%-10%), septicemia, psoas abscess, liver abscess, portal hypertension in children[14-17,19,20,23,24,26,31,33,35], etc. TB-related intestinal perforation is responsible for 4%-30% of all the non-traumatic terminal ileal perforations[22,37] and for 10% of all perforation peritonitis[35]. Solitary intestinal perforation occurs in 90% of the cases, but 10%-40% of the patients can present multiple perforations[16,24,33], such as in our patient’s case. The rate of mortality in patients with TB-induced diffuse peritonitis is between 13% and 100%[16,33,35].

In patients receiving anti-TB therapy, paradoxical intestinal perforation was reported 14-270 d from the initiation of the therapeutic regimen, probably as a result of a delayed hypersensitivity response[24,33]. This paradoxical phenomenon is more frequent in patients with primary or acquired immunodeficiency diseases, such as defective mitogen-induced interleukin-12 production[33] and human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients receiving active anti-retroviral therapy[24].

Another unusual complication of the distal ileum TB, which especially occurs in children, is that of B12 deficiency. It can induce macrocytic anemia and neuropathy with brain atrophy and seizures. The main clinical symptoms are paraplegia, ataxia, fever, fatigue, urinary incontinence and dysarthria[28]. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy was also seen to be associated with intestinal TB[41]. In patients with neurological abnormalities, the following conditions (except TB) should be also taking into account: Malnutrition, regional enteritis, Whipple’s disease and other gastrointestinal disorders, abuse of valproic acid and paraneoplastic syndromes should be excluded[28,29].

The correct etiological diagnosis of IBD is indispensable for proper therapy (Table 1) because unnecessary anti-TB therapy increases the risk of toxicity and multi-drug resistance and delays the treatment of CD, whereas steroids and infliximab (usually used for CD) can accelerate the TB’s dissemination and favor intestinal perforation[12,33,34,39]. In patients with neurological abnormalities, administration of vitamin B12 can accelerate the evolution of an undiagnosed tumor, which can be responsible for paraneoplastic neuropathy. Moreover, because TB responds to anti-TB agents, extensive surgical interventions should be avoided, especially in children[17,20,21,24]. In patients with CD, the therapeutically management should also taken into account the immune-induced endothelial modifications and vascular dysfunctions[42,43]. Due to the higher percentage of atherosclerosis-related complications in these patients[42,43], a complex cardiovascular investigation is mandatory before establishing the therapeutically regimen.

In patients that do not undergo surgery, ileocecal stricture and luminal stenosis are the main late complications. These complications appear in one third of the patients and can be treated using endoscopic balloon dilatation[27,38]. They predispose to enterolithiasis in 3% of the patients, with further intestinal strictures, obstructions, perforations, or hematochezia[32].

This case highlights the necessity of including TB enterocolitis as a differential diagnosis in patients with non-specific abdominal symptoms and the difficulty inherent in the differentiation of gastrointestinal TB from CD. In a child with prolonged fever of an unknown origin, TB suspicions should be taken into account. It can also be considered as a contributing factor in patients with neuropathies.

A 53-year-old male with acute peritonitis as result of ileal perforation.

Skip ulcerations of the terminal ileum, probably Crohn’s disease, peritonitis and septic shock.

Other inflammatory bowel diseases, including ischemic colitis, indeterminate enterocolitis, tuberculosis, angiodysplasia.

Non-specific - slight anemia and leukocytosis.

Thoracic radiography - bilateral bronchopneumonia.

Postmortem examination of surgical specimens revealed tuberculous ileotyphlitis with tuberculous mesenteric lymphadenopathy and miliary tuberculous granulomas in upper lobes of the lungs, liver and spleen.

Right hemicolectomy with terminal ileum resection. Death was installed 4 d postoperatively.

Few than 50 reports add new data in field of intestinal tuberculosis. Its incidence increased in the last two decades and most of the cases are improper diagnosed. An incorrect diagnosis increases the severity of this disease.

Tuberculous ileotyphlitis is also known as intestinal tuberculosis involving the terminal ileus and cecum. Hematochezia represents rectal bleeding and can be a sign of an intestinal inflammatory bowel disease.

This case report shows the necessity of complete exploration of the patient, to identify the associated lesions, and the difficulty of differential diagnosis of terminal ileitis.

A very good presentation of a case of intestinal tuberculosis which is often forgotten in differential diagnosis clinically.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine

Country of origin: Romania

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B, B, B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cao SS, Ciccone MM, Matsuda A, Pearson JS, Saniabadi AR, Smids C S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Burke KA, Patel A, Jayaratnam A, Thiruppathy K, Snooks SJ. Diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis in the acute abdomen. Int J Surg. 2014;12:494-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wijewantha HS, de Silva AP, Niriella MA, Wijesinghe N, Waraketiya P, Kumarasena RS, Dassanayake AS, Hewawisenthi Jde S, de Silva HJ. Usefulness of Routine Terminal Ileoscopy and Biopsy during Colonoscopy in a Tropical Setting: A Retrospective Record-Based Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2014;2014:343849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Niriella MA, De Silva AP, Dayaratne AH, Ariyasinghe MH, Navarathne MM, Peiris RS, Samarasekara DN, Satharasinghe RL, Rajindrajith S, Dassanayake AS. Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in two districts of Sri Lanka: a hospital based survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dilauro S, Crum-Cianflone NF. Ileitis: when it is not Crohn’s disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2010;12:249-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mirzoian EZ. [Differential diagnosis of tuberculous ileo-typhilitis with non-specific diseases of the abdominal cavity]. Sov Med. 1957;21:87-91. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mirzoian EZ. [Experience in the use of antibacterial chemotherapy in treatment of ileotyphlitis without active lung process]. Probl Tuberk. 1957;35:47-53. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Schwarz KO, Cohen A, Hertz IH. Tuberculous ileotyphlitis with formation of large ileal pseudopolyp mimicking tumor. Mt Sinai J Med. 1982;49:421-425. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dantsig II, Loseva TL, Levin NF. [Tuberculous ileotyphlitis]. Khirurgiia (Mosk). 1999;64. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kedia S, Kurrey L, Pratap Mouli V, Dhingra R, Srivastava S, Pradhan R, Sharma R, Das P, Tiwari V, Makharia G. Frequency, natural course and clinical significance of symptomatic terminal ileitis. J Dig Dis. 2016;17:36-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ng SC, Chan FK. Infections and inflammatory bowel disease: challenges in Asia. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:567-573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hermon-Taylor J, Barnes N, Clarke C, Finlayson C. Mycobacterium paratuberculosis cervical lymphadenitis, followed five years later by terminal ileitis similar to Crohn’s disease. BMJ. 1998;316:449-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Rane PS. Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in India where tuberculosis is widely prevalent. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:741-746. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Briley CA, Jackson DC, Johnsrude IS, Mills SR. Acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage of small-bowel origin. Radiology. 1980;136:317-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Anand AC, Patnaik PK, Bhalla VP, Chaudhary R, Saha A, Rana VS. Massive lower intestinal bleeding--a decade of experience. Trop Gastroenterol. 2001;22:131-134. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sefr R, Rotterová P, Konecný J. Perforation peritonitis in primary intestinal tuberculosis. Dig Surg. 2001;18:475-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Al Salamah SM, Bismar H. Acute ileal tuberculosis perforation: a case report. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2002;8:64-66. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Ozbey H, Tireli GA, Salman T. Abdominal tuberculosis in children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2003;13:116-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Engin G, Balk E. Imaging findings of intestinal tuberculosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005;29:37-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park JK, Lee SH, Kim SG, Kim HY, Lee JH, Shim JH, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. [A case of intestinal tuberculosis presenting massive hematochezia controlled by endoscopic coagulation therapy]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2005;45:60-63. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Boukthir S, Mrad SM, Becher SB, Khaldi F, Barsaoui S. Abdominal tuberculosis in children. Report of 10 cases. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2004;67:245-249. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Balsara KP, Shah CR, Maru S, Sehgal R. Laparoscopic-assisted ileo-colectomy for tuberculosis. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:986-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wani RA, Parray FQ, Bhat NA, Wani MA, Bhat TH, Farzana F. Nontraumatic terminal ileal perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2006;1:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Leung VK, Law ST, Lam CW, Luk IS, Chau TN, Loke TK, Chan WH, Lam SH. Intestinal tuberculosis in a regional hospital in Hong Kong: a 10-year experience. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:264-271. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Leung VK, Chu W, Lee VH, Chau TN, Law ST, Lam SH. Tuberculosis intestinal perforation during anti-tuberculosis treatment. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:313-315. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Kapan M, Karabicak I, Aydogan F, Kusaslan R, Kisacik B. Intestinal perforation due to miliary tuberculosis in a patient with Behcet’s disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:825-827. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Polat KY, Aydinli B, Yilmaz O, Aslan S, Gursan N, Ozturk G, Onbas O. Intestinal tuberculosis and secondary liver abscess. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73:887-890. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Akarsu M, Akpinar H. Endoscopic balloon dilatation applied for the treatment of ileocecal valve stricture caused by tuberculosis. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:597-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Toosi TD, Shahi F, Afshari A, Roushan N, Kermanshahi M. Neuropathy caused by B12 deficiency in a patient with ileal tuberculosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;2:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Jung I, Gurzu S, Balasa R, Motataianu A, Contac AO, Halmaciu I, Popescu S, Simu I. A coin-like peripheral small cell lung carcinoma associated with acute paraneoplastic axonal Guillain-Barre-like syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e910. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Surlin V, Georgescu E, Comănescu V, Mogoantă SS, Georgescu I. Ileal iterative spontaneous perforation from foreign body granuloma: problems of histopathologic diagnosis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2009;50:749-752. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Miura T, Shimizu T, Nakamura J, Yamada S, Yanagi M, Usuda H, Emura I, Takahashi T. [A case of intestinal tuberculosis associated with ileo-ileal fistula]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2010;107:416-426. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Negi SS, Sud R, Chaudhary A. Tubercular ileal stricture with enterolithiasis presenting as massive lower gastrointestinal bleed. Trop Gastroenterol. 2010;31:47-48. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Law ST, Chiu SC, Li KK. Intestinal tuberculosis complicated with perforation during anti-tuberculous treatment in a 13-year-old girl with defective mitogen-induced IL-12 production. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2014;47:441-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cappell MS, Saad A, Bortman JS, Amin M. Ileocolonic tuberculosis clinically, endoscopically, and radiologically mimicking Crohn’s disease: disseminated infection after treatment with infliximab. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:560-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yadav D, Garg PK. Spectrum of perforation peritonitis in delhi: 77 cases experience. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:133-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Surewad G, Lobo I, Shanbag P. Pulmonary and ileal tuberculosis presenting as Fever of undetermined origin. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:PD01-PD02. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Khalid S, Burhanulhuq AA. Non-traumatic spontaneous ileal perforation: experience with 125 cases. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2014;26:526-529. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Gan H, Mely M, Zhao J, Zhu L. An Analysis of the Clinical, Endoscopic, and Pathologic Features of Intestinal Tuberculosis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:470-475. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Zhang T, Fan R, Wang Z, Hu S, Zhang M, Lin Y, Tang Y, Zhong J. Differential diagnosis between Crohn’s disease and intestinal tuberculosis using integrated parameters including clinical manifestations, T-SPOT, endoscopy and CT enterography. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8:17578-17589. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Ihama Y, Hokama A, Hibiya K, Kishimoto K, Nakamoto M, Hirata T, Kinjo N, Cash HL, Higa F, Tateyama M. Diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis using a monoclonal antibody to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6974-6980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chong VH, Joseph TP, Telisinghe PU, Jalihal A. Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy associated with intestinal tuberculosis. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2007;40:377-380. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Ciccone MM, Principi M, Ierardi E, Di Leo A, Ricci G, Carbonara S, Gesualdo M, Devito F, Zito A, Cortese F. Inflammatory bowel disease, liver diseases and endothelial function: is there a linkage? J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown). 2015;16:11-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Principi M, Mastrolonardo M, Scicchitano P, Gesualdo M, Sassara M, Guida P, Bucci A, Zito A, Caputo P, Albano F. Endothelial function and cardiovascular risk in active inflammatory bowel diseases. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e427-e433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |