Published online Sep 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i9.264

Peer-review started: April 28, 2016

First decision: June 16, 2016

Revised: July 8, 2016

Accepted: July 20, 2016

Article in press: July 22, 2016

Published online: September 16, 2016

Processing time: 132 Days and 15.9 Hours

Paediatric Chance fracture are rare lesions but often associated with abdominal injuries. We herein present the case of a seven years old patient who sustained an entrapment of small bowel and an ureteropelvic disruption associated with a Chance fracture and spine dislocation following a traffic accident. Initial X-rays and computed tomographic (CT) scan showed a Chance fracture with dislocation of L3 vertebra, with an incarceration of a small bowel loop in the spinal canal and a complete section of the left lumbar ureter. Paraplegia was noticed on the initial neurological examination. A posterior L2-L4 osteosynthesis was performed firstly. In a second time she underwent a sus umbilical laparotomy to release the incarcerated jejunum loop in the spinal canal. An end-to-end anastomosis was performed on a JJ probe to suture the left injured ureter. One month after the traumatism, she started to complain of severe headaches related to a leakage of cerebrospinalis fluid. Three months after the traumatism there was a clear regression of the leakage. One year after the trauma, an anterior intervertebral fusion was done. At final follow-up, no neurologic recovery was noticed. In case of Chance fracture, all physicians should think about abdominal injuries even if the patient is asymptomatic. Initial abdominal CT scan and magnetic resonance imaging provide in such case crucial info for management of the spine and the associated lesions.

Core tip: We report the case of a 7 years old patient with a Chance fracture and dislocation of the 3rd lumbar vertebra associated with abdominal injuries and cauda equina syndrome. Initial radiological examinations led to a multidisciplinary surgical management. Particular attention must be paid to these lesions in the initial evaluation.

- Citation: Pesenti S, Blondel B, Faure A, Peltier E, Launay F, Jouve JL. Small bowel entrapment and ureteropelvic junction disruption associated with L3 Chance fracture-dislocation. World J Clinical Cases 2016; 4(9): 264-268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i9/264.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i9.264

Bowel injuries may be seen in conjunction with spinal fractures, especially in patients who have been involved in motor vehicle accidents. The seat belt, while preventing some types of injuries, may predispose to serious injuries by rapid angulation of the spine and compression of the abdominal contents[1]. We report a unique case of preoperative diagnosis of jejunum entrapment into the vertebral body of L3, associated with ureteropelvic junction disruption and fracture-dislocation of the L3 vertebra.

A seven years old girl was sitting in the rear seat of a car with her abdominal seatbelt fastened when the vehicle was involved in a high speed head-on collision. The grandmother, rear sitting too, had an ankle fracture.

When arriving at the emergency department, physical examination of the patient revealed lumbar pain, abdominal pain and paraplegia. The abdomen was diffusely tender and neurologic examination showed a caudal equina syndrome with a sensory deficit corresponding to level L3, a decreased rectal tone and paraplegia.

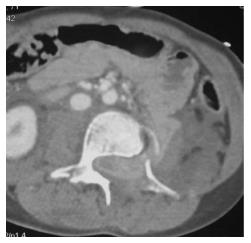

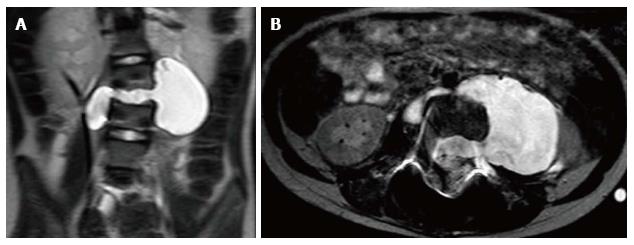

Radiologic evaluation included X-rays, computed tomographic (CT)-scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). These examinations showed a Chance type fracture with dislocation of vertebra L3 (Figure 1) with entrapment of a small bowel loop in the spinal canal (Figure 2), a splenic subhilar fracture with perisplenic free fluid, difficulty to follow the left ureter at the lumbar level and a fracture of the right ischiopubic branch. MRI confirmed the aspect of small bowel loop into the spinal canal.

She underwent a two-stage emergency surgery. Firstly, the patient was placed in a prone position. A prophylactic antibiotic treatment was performed, using a 3rd generation cephalosporin. The Chance fracture was treated by open reduction and osteosynthesis by pedicular fixation from L2 to L4. Secondary she underwent left transverse susombilical laparotomy. It revealed the intracanalar incarceration of a jejunum loop (Figure 3), an injury of the ascending colon, a large section of the retroperitoneum at L3 level, a section of the left psoas muscle, a complete section of the left lumbar ureter and a left lumbar arterial wound. No obvious sign of hepatic or pancreatic injury were observed. The L3-L4 discectomy was performed to release the incarcerated bowel loop. A 10 cm-small bowel resection was performed because of the suffering aspect of the incarcerated bowel fragment. A primary end-to-end anastomosis was performed and the perivertebral space was irrigated. The injured left ureter was then sutured end-to-end on a JJ probe (18 cm, 4.7 Charriere). The right colonic serosa wound was closed and the retroperitoneum was drained.

Antibiotics were continued postoperatively to prevent meningitis and peritonitis. A removable thoracolumbar brace was prescribed. She didn’t show any neurologic recovery after surgery.

This young girl was discharged from the hospital on day 12. The JJ probe was removed one month after the traumatism and intermittent bladder catheterization were initiated.

She started to complain of severe headaches in sitting position that completely resolved with recumbent position. An MRI was performed for a suspicion of dural tear. It showed a leakage of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the medullary canal to the abdominal cavity, through the L3-L4 intervertebral disc and the left L3-L4 intervertebral foramen (Figure 4). The abdominal meningocele was developed along the left psoas muscle. It was decided to follow up this collection by ultrasonography. After one week, the patient could tolerate the seated position without any complain. Ultrasonography controls didn’t show any increase of the meningocele. The patient was discharged from the hospital and was asked to wear a full time brace. Three and a half months after the traumatism, an MRI showed a clear decrease of the meningocele. Three months after, CSF signal was only visible at the level of the L3-L4 intervertebral disc space, and disappeared 6 mo later.

One year after the traumatism, the patient finally underwent an anterior L2-L4 anterior interbody fusion through a standard left lobotomy. No LCS leakage was identified during this surgical procedure. The L2-L3 intervertebral disc and the remnants of the L3-L4 intervertebral disc were removed and replaced by cancellous bone grafts, without osteosynthesis.

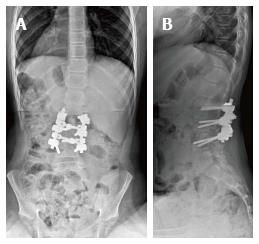

At last follow up (9 mo after the second surgical procedure), the patient still did not show any neurologic recovery. The evoked somatosensory potentials didn’t show any neurologic activity in both legs. The AP and lateral full spine x-rays performed in the seated position showed satisfactory spine morphology (Figure 5).

The optimal seatbelt links the thorax to the pelvis. In children, the shoulder restraint is usually in front of the face or neck and therefore often removed. The lap belt is frequently placed alone directly across the abdomen, creating an axis of rotation near the level of the umbilicus during a collision[2,3]. The hyperflexion of the upper body over the lapbelt produces flexion-distraction forces and classically causes a Chance fracture of the spine. Nonetheless, 40% of these injuries occur while wearing a combined shoulder and lap belt[4]. Nance et al[5] had showed that optimally restrained children were at a significantly lower risk of abdominal injury (5%) than children suboptimally restrained (17%) for their age.

The exact mechanism of traumatic incarceration of bowel in the spine is unclear. Nowadays two theories are proposed. According to some authors, an anterior force pushes the bowel while other authors explain the bowel incarceration by a posterior vacuum responsible of a traction force[6-11]. In our case, the findings support the concept that the anterior dislocation of the L3 vertebra tore up the posterior peritoneum and brought back the jejunum loop in the spinal canal.

Small bowel injury in children is uncommon with an incidence estimated between 1% to 7%[12]. The most common injuries are duodenal perforation or haematoma, mesenteric contusions, avulsion of the jejunum at the duodenal jejunal flexure, ileal or jejunal perforations and evisceration of the small bowel[13].

Ureteric injury following abdominal trauma represents less than 1% of all urologic trauma. Avulsion of the ureteropelvic junction is the most common injury in children[14,15] as the pelvis and the psoas muscles provide protection to the distal collecting system. A hypothesis to explain the avulsion of the ureteropelvic junction is that acceleration-deceleration forces provoke an anterosuperior displacement of the kidney while the ureter remains in a fixed position[16]. The hyperextension of the trunk stretches the ureter and a rapid deceleration compresses the ureter against the vertebral column.

Delayed diagnosis appears to cause significant morbidity and mortality in children with blunt abdominal trauma[17,18]. The main problem is the difficulty to diagnose associated lesions. The pain relative to the spine fracture often conceals abdominal signs. Abdominal wall haematoma may alter clinical examination and hide intra-abdominal injuries. CT-scan and abdominal ultrasound are often used to screen these injuries before surgical exploration. CT-scan is already a relatively non-invasive modality that provides data on any concomitant abdominal, spinal or retroperitoneal injuries. Although delayed diagnosis of visceral injuries after abdominal CT scanning has been reported in 10% to 50% of such patients[19]. In the other hand, in most cases abdominal symptoms dominate and the diagnosis of Chance fracture is delayed. In our case, the association of neurological and abdominal symptoms after a high-speed head-on car collision led us to realize urgent CT-scan and MRI. This attitude allowed a rapid diagnosis. It is interesting to point out that the diagnosis of this association of injuries before surgery has never been described, even if cases of pneumorachis has been published[20,21].

Concerning the surgical management, we think that performing the laparotomy first could have been dangerous because of the major instability of the spine. Indeed, there would have been a high risk of iatrogenic injuries while mobilizing the patient. For this reason, the posterior arthrodesis was done firstly, in order to stabilize the spine, the hemodynamic stability and the absence of vascular emergency allowed to proceed this way. Moreover, Crawford et al[21] think that the reduction and stabilization of the spinal injuries should be performed as early as possible. Spine stabilization facilitates safe mobilization of the patient and avoids potential secondary injury to intra-abdominal structures. In our case, anterior spinal stabilization was not immediately performed because of the high infectious risk (osteitis, meningitis) in the context of bowel injury.

During the postoperative course, our patient presented a delayed CSF leakage. The time interval was 30 d. Most of post-traumatic CSF leakage resolves within 6 mo after the traumatism without surgical management. The rate of spontaneous healing of traumatic CSF leaks has been reported around 53%[22].

The appropriate timing for surgical intervention is also unclear. In our case we decided to treat the persistent post-traumatic CSF leak conservatively with bed rest in Trendelenburg position. We did not perform an anterior spinal stabilization at month 1 because lumbar spine injuries were stable. Overall management results were quite satisfactory, with no mortality or wound infections.

In case of spinal trauma caused by head-on collision despite of seat belt wearing, all physicians should think about abdominal injuries even if the patient is asymptomatic, and perform an abdominal CT scan and MRI as soon as possible. An early diagnosis of associated injuries contributes to the optimal management of this kind of patients.

Intracanalar entrapment of jejunum loop in children is an uncommon but serious injury following blunt abdominal trauma. This attitude seems the most appropriate for a multidisciplinary management of these lesions.

Paraplegia, back pain and abdominal pain in a 7 years old patient after a high-speed car accident.

Chance fracture of the 3rd lumbar vertebra dislocation of the spine associated with small bowel entrapment ant disruption of the ureteropelvic junction.

Systematic computed tomographic (CT)-scan an magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of blunt abdominal trauma allow a complete diagnosis and avoid to miss abdominal or bony injuries.

Off topic in this case.

CT-scan and MRI are useful in this case, both for the diagnosis of intra-abdominal injuries and bony lesions of the spine.

While abdominal injuries are often associated with Chance fracture, the entrapment of a small bowel loop into the medullary canal is uncommon and must be diagnosed preoperatively.

A two-time surgical management was performed initially, a posterior decompression and osteosynthesis of the spine firstly and then a resection-anastomosis of the small bowel and an end-to-end anastomosis of the ureteropelvic junction.

After a high-speed car accident, physicians must pay attention to abdominal symptoms associated to back pain. Chance fractures are often associated with abdominal injuries. All the lesions must be managed at the same time. The cerebrospinal fluid leakage that appeared after surgery has been watched and was resolved at one-year follow-up.

The present manuscript is a first report about pre-operative diagnosis of both Chance fracture and small bowel entrapment at the fracture site in a 7 years old child. The case report is simply and clearly exposed, the documentation is fine, and the discussion is also well developed.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Narayanan SK, Vannucci L S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Appleby JP, Nagy AG. Abdominal injuries associated with the use of seatbelts. Am J Surg. 1989;157:457-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gumley G, Taylor TK, Ryan MD. Distraction fractures of the lumbar spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64:520-525. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Smith MD, Camp E, James H, Kelley HG. Pediatric seat belt injuries. Am Surg. 1997;63:294-298. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Mulpuri K, Jawadi A, Perdios A, Choit RL, Tredwell SJ, Reilly CW. Outcome analysis of chance fractures of the skeletally immature spine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:E702-E707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nance ML, Lutz N, Arbogast KB, Cornejo RA, Kallan MJ, Winston FK, Durbin DR. Optimal restraint reduces the risk of abdominal injury in children involved in motor vehicle crashes. Ann Surg. 2004;239:127-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Beaunoyer M, St-Vil D, Lallier M, Blanchard H. Abdominal injuries associated with thoraco-lumbar fractures after motor vehicle collision. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:760-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Davis RE, Mittal SK, Perdikis G, Richards AT, Fitzgibons RJ. Traumatic hyperextension/hyperflexion of the lumbar vertebrae with entrapment and strangulation of small bowel: case report. J Trauma. 2000;49:958-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Eldridge TJ, McFall TM, Peoples JB. Traumatic incarceration of the small bowel: case report. J Trauma. 1993;35:960-961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Patterson R, Temple WJ, Tranmer B, Miller SD. Traumatic intervertebral incarceration of ileum: a unique lap belt injury. Injury. 1996;27:596-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Reid AB, Letts RM, Black GB. Pediatric Chance fractures: association with intra-abdominal injuries and seatbelt use. J Trauma. 1990;30:384-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Rodger RM, Missiuna P, Ein S. Entrapment of bowel within a spinal fracture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1991;11:783-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mercer S, Legrand L, Stringel G, Soucy P. Delay in diagnosing gastrointestinal injury after blunt abdominal trauma in children. Can J Surg. 1985;28:138-140. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Holland AJ, Cass DT, Glasson MJ, Pitkin J. Small bowel injuries in children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2000;36:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mollitt DL, Ballantine TV, DeRosa GP. Jejuno-renal injury following traumatic hyperextension. J Trauma. 1980;20:996-998. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Palmer JM, Drago JR. Ureteral avulsion from non-penetrating trauma. J Urol. 1981;125:108-111. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Slobogean GP, Tredwell SJ, Masterson JS. Ureteropelvic junction disruption and distal ureter injury associated with a Chance fracture following a traffic accident: a case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2007;15:248-250. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Bensard DD, Beaver BL, Besner GE, Cooney DR. Small bowel injury in children after blunt abdominal trauma: is diagnostic delay important? J Trauma. 1996;41:476-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Meyer DM, Thal ER, Coln D, Weigelt JA. Computed tomography in the evaluation of children with blunt abdominal trauma. Ann Surg. 1993;217:272-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Tso EL, Beaver BL, Haller JA. Abdominal injuries in restrained pediatric passengers. J Pediatr Surg. 1993;28:915-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Silver SF, Nadel HR, Flodmark O. Pneumorrhachis after jejunal entrapment caused by a fracture dislocation of the lumbar spine. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1988;150:1129-1130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kara H, Akinci M, Degirmenci S, Bayir A, Ak A. Traumatic pneumorrhachis: 2 cases and review of the literature. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33:861.e1-861.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Persistent posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9:e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |