Published online Aug 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i8.248

Peer-review started: April 23, 2016

First decision: May 17, 2016

Revised: May 24, 2016

Accepted: June 14, 2016

Article in press: June 16, 2016

Published online: August 16, 2016

Processing time: 111 Days and 17.7 Hours

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare but serious protein-losing enteropathy, but little is known about the mechanism. Further more, misdiagnosis is common due to non-familiarity of its clinical manifestation. A 40-year-old male patient was admitted to our hospital because of diarrhea and hypogeusia associated with weight loss for 4 mo. On physical examination, skin pigmentation, dystrophic nail changes and alopecia were noted. He had no alike family history. Laboratory results revealed low levels of serum albumin (30.1 g/L, range: 35.0-55.0 g/L), serum potassium (2.61 mmol/L, range: 3.5-5.5 mmol/L) and blood glucose (2.6 mmol/L, range: 3.9-6.1 mmol/L). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated to 17 mm/h (range: 0-15 mm/h). X-ray of chest and mandible was normal. The endoscopic examination showed multiple sessile polyps in the stomach, small bowel and colorectum. Histopathologic examination of biopsies obtained from those polyps showed hyperplastic change, cystic dilatation and distortion of glands with inflammatory infiltration, eosinophilic predominance and stromal edema. Immune staining for IgG4 plasma cells was positive in polyps of stomach and colon. The patient was diagnosed of CCS and treated with steroid, he had a good response to steroid. Both histologic findings and treatment response to steroid suggested an autoimmune mechanism underling CCS.

Core tip: Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a non-hereditary condition characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis associated with diarrhea and epidermal manifestations. It is a rare but serious disease, early diagnosis can improve prognosis of the patients, but delay in diagnosis is common due to non-familiarity of its clinical manifestation. Here we report a case of a patient with CCS, in this report showed the patient’s clinical characteristics and response to treatment.

- Citation: Fan RY, Wang XW, Xue LJ, An R, Sheng JQ. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome polyps infiltrated with IgG4-positive plasma cells. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(8): 248-252

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i8/248.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i8.248

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome (CCS) is a rare, non-hereditary condition characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis associated with diarrhea and epidermal manifestations, such as cutaneous hyperpigmentation, alopecia and onychodystrophy[1]. So far, the pathogenesis of CCS is still not fully understood[2], and autoimmune mechanism is probably involved. We here report a case of CCS in a male patient whose polyps presented with IgG4 - positive plasma cells. This finding is consistent with the autoimmune mechanism underlying CCS.

A 40-year-old male patient with a 4-mo history of non-bloody watery diarrhea and hypogeusia associated with weight loss was admitted to our hospital in October of 2015. He defecated 6 to 10 times daily. No blood, mucosa, fat or oil was observed in the stool. He had no fever and abdominal pain. Family history was negative. In the past 4 mo, the patient experienced a weight loss of 17 kg.

Vital signs on physical examination were normal. His nutritional status was poor. Systemic skin pigmentation, dystrophic nail changes (Figure 1A and B) and alopecia (Figure 1C) were noted, but there was no pigmentation within oral cavity. The rest of the physical examination was non-contributory.

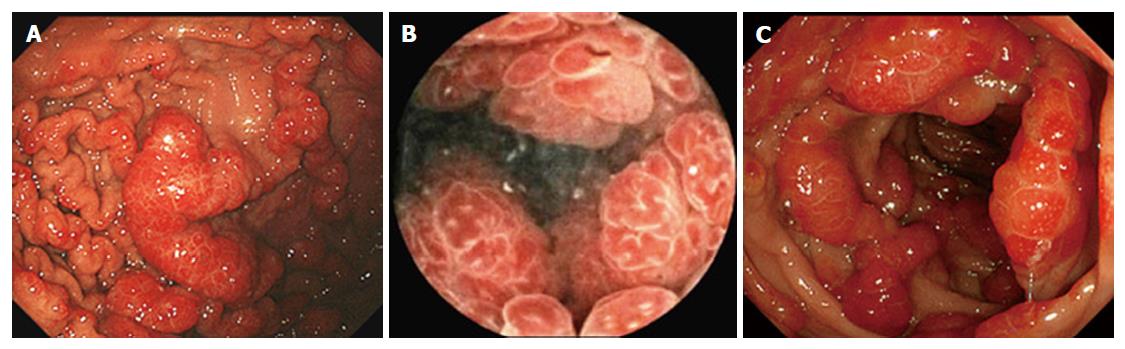

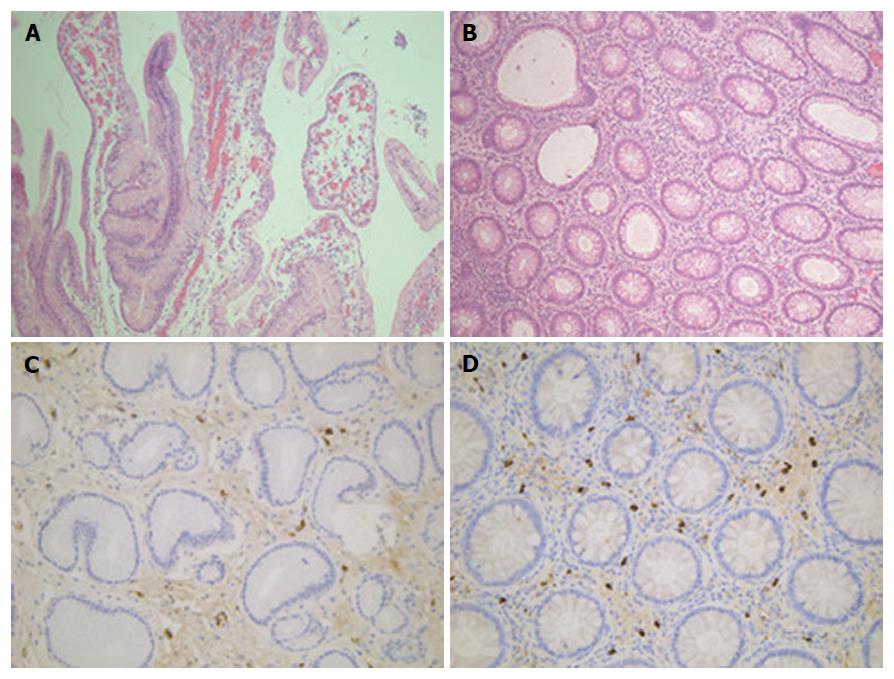

Laboratory results revealed low levels of serum albumin (30.1 g/L, range: 35.0-55.0g/L), serum potassium (2.61 mmol/L, range: 3.5-5.5 mmol/L) and blood glucose (2.6 mmol/L, range: 3.9-6.1 mmol/L). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated to 17 mm/h (range: 0-15 mm/h). The C reaction protein was within normal ranges. Both serum IgG4 (0.42 g/L, range: 0.08-1.4 g/L), and serum total IgG were normal (6.16 g/L, range: 6.0-16.0 g/L). Antinuclear antibody, anti-mitochondrial antibody, and smooth muscle antibody were all negative. There were no abnormal findings in X-ray of chest and mandible. The patient underwent electron esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy, capsule endoscopy and electronic colonoscopy, respectively, after admission. The endoscopic evaluation revealed multiple sessile polyps in the stomach (Figure 2A), small bowel (Figure 2B), and colon and rectum (Figure 2C). Histopathologic examination of biopsies obtained from those polyps showed hyperplastic change, cystic dilatation and distortion of glands with inflammatory infiltration, esinophillic predominance and stromal edema (Figure 3A and B). The histopathology of his rectal polyp showed a serrated adenoma. Mild chronic inflammation was found in the rectal mucosa which appeared normal under endoscope. Esophagogastroduodenal endoscopy revealed an esophageal papilloma, but did not show polyp of the esophageal mucoma.

Immune staining for IgG4 plasma cells was positive in polyps of stomach (Figure 3C) and colon (Figure 3D), and IgG4 positive cell count of each high power field was 0-3 and 10-18 in gastric and colonic polyps, respectively. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome was diagnosed based on a combination of clinical features, endoscopic findings and histopathology of polyps. The patient was given nutrition support and symptomatic treatment, and his symptom of diarrhea improved. The patient refused steroid treatment and was discharged.

After a month, he was admitted to our hospital again because of severe diarrhea. By consent, he started on steroid treatment, and was administered methylprednisolone 40 mg/d intravenously for 6 d. His condition became much better, and was discharged. The patient was then treated with prednisone 30 mg/d orally for 4 wk, tapered by 2.5-5 mg/d every 1-2 wk. Follow-up was carried out at 8 wk after discharge, his diarrhea was improved, taste returned to normal and weight gain was 5.0 kg.

CCS was first described in 1955 by Leonard W. Cronkhite, and Wilma J. Canada[1]. It occurs most frequently in middle-aged or older adults, with a slight male predominance, and a male-to-female ratio of 3:2[3]. CCS is a rare but serious protein-losing enteropathy, classically characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis and ectodermal features. Gastrointestinal polyposis is closely related to the malabsorption which induced these ectodermal changes[4]. There is no strong evidence to suggest a familial aggregation and genetic predisposition. The etiology remains obscure but immune dysregulation may be important, given the increased IgG4 mononuclear cell staining in CCS polyps[5,6]. In this case, IgG4 immunostaining was positive in polyps of stomach and colon. This histologic finding further supports that autoimmune mechanism may be involved in CCS.

Differential diagnosis of CCS includes a number of polyposis syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden disease, Turcot syndrome and juvenile polyposis. These can be distinguished based on the polyp histology, polyp distribution, clinical presentations, family history, and molecular genetic testing[7]. Polyps in CCS patients can develop throughout the gastrointestinal tract (except the esophagus) and are usually non-neoplastic hamartomas[5]. But polyps of CCS also displayed hyperplastic, inflammatory, or adenomatous features[8]. Watanabe et al[9] demonstrasted common features typical of CCS polyps, such as focal dilated cystic glands, some filled with proteinaceous fluid or inspissated mucus, the polyp and interpolyp area was edematous, with congestion and chronic inflammation of the lamina propria and submucosa, even though endoscopically the mucosa appeared normal. These findings are consistent with our case.

Optimum therapy for CCS is not known because of the rarity of the disorder and the poor understanding of the etiology. Combination therapy based on nutritional support and corticosteroids appears to lessen symptoms. The total treatment period is also not evidence-based, some recommended a range from 6 to 12 mo[10,11]. Relapse was common with steroid tapering. For some patients with CCS who initially responded to corticosteroids, long-term maintenance therapy by azathioprine may decrease its recurrence rate[5]. Our case had a good response to corticosteroids for 9 wk, but long-term efficacy is uncertain, and follow-up is needed in the future.

CCS has a rather poor prognosis, with a 5-year mortality rate of only 55%[12]. Delay in diagnosis are common primarily due to non-familiarity of physicians with this rare entity or nonspecific manifestation of early CCS, leading to poor outcome[13,14]. CCS bears a risk of malignancy development, and adenomatous polyps may occasionally occur in CCS patients, which are precursor lesions of colorectal cancer[15]. In the present case, colonoscopy showed a serrated adenoma in rectal mucosa. Intensive follow-up should be carried out in order to prevent and find canceration.

In summary, CCS is a rare disease with poor prognosis, autoimmune mechanism is probably involved in its pathogenesis. It has a good response to steroid. CCS has the risk of gastrointestinal cancer development and requires regular endoscopic surveillance.

A 40-year-old male patient with a 4-mo history of diarrhea and hypogeusia associated with weight loss.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome.

Familial adenomatous polyposis, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, Cowden disease, Turcot syndrome, juvenile polyposis.

Low levels of serum albumin (30.1 g/L) and serum potassium (2.61 mmol/L).

The endoscopic evaluation revealed multiple sessile polyps in the stomach, small bowel and colorectum.

The patient was treated with steriod.

Cronkhite-Canada syndrome is a rare and serious disease, but few report is related to the mechanism.

For the patient with Cronkhite-Canada syndrome, early diagnosis and follow-up is import to improve the prognosis. Immune staining for IgG4 plasma cells in the polpys is helpful for exploring the mechanism underling cronkhite-canada syndrome.

In this manuscript, the authors demonstrated interesting Cronkhite-Canada syndrome case.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Freeman HJ, Hosoe N S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Cronkhite LW, Canada WJ. Generalized gastrointestinal polyposis; an unusual syndrome of polyposis, pigmentation, alopecia and onychotrophia. N Engl J Med. 1955;252:1011-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 292] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Safari MT, Shahrokh S, Ebadi S, Sadeghi A. Cronkhite- Canada syndrome; a case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2016;9:58-63. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Review article: the non-inherited gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:333-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Seshadri D, Karagiorgos N, Hyser MJ. A case of cronkhite-Canada syndrome and a review of gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:197-201. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sweetser S, Ahlquist DA, Osborn NK, Sanderson SO, Smyrk TC, Chari ST, Boardman LA. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: support for autoimmunity. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:496-502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bettington M, Brown IS, Kumarasinghe MP, de Boer B, Bettington A, Rosty C. The challenging diagnosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome in the upper gastrointestinal tract: a series of 7 cases with clinical follow-up. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shen XY, Husson M, Lipshut W. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome: A Case Report and Literature Review of GastrointestinalPolyposis Syndrome. Case Rep Clin Med. 2014;3:650-659. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wen XH, Wang L, Wang YX, Qian JM. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: report of six cases and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7518-7522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watanabe C, Komoto S, Tomita K, Hokari R, Tanaka M, Hirata I, Hibi T, Kaunitz JD, Miura S. Endoscopic and clinical evaluation of treatment and prognosis of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a Japanese nationwide survey. J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:327-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sweetser S, Boardman LA. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: an acquired condition of gastrointestinal polyposis and dermatologic abnormalities. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:201-203. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ward EM, Wolfsen HC. Pharmacological management of Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4:385-389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Daniel ES, Ludwig SL, Lewin KJ, Ruprecht RM, Rajacich GM, Schwabe AD. The Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome. An analysis of clinical and pathologic features and therapy in 55 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 1982;61:293-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xue LY, Hu RW, Zheng SM, Cui de J, Chen WX, Ouyang Q. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome: a case report and review of literature. J Dig Dis. 2013;14:203-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chakrabarti S. Cronkhite-Canada Syndrome (CCS)-A Rare Case Report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:OD08-OD09. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Malhotra R, Sheffield A. Cronkhite-Canada syndrome associated with colon carcinoma and adenomatous changes in C-C polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:772-776. [PubMed] |