Published online Aug 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i8.238

Peer-review started: March 2, 2016

First decision: April 15, 2016

Revised: May 4, 2016

Accepted: May 31, 2016

Article in press: June 2, 2016

Published online: August 16, 2016

Processing time: 163 Days and 21 Hours

A 73-year-old man underwent endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of a 20-mm flat elevated lesion on the transverse colon. The morning after the procedure, he started to have severe right upper quadrant pain after his first meal. A computed tomography scan revealed free air and a stomach filled with food. He was diagnosed to have delayed post-EMR intestinal perforation. He underwent emergent colonoscopy and clipping of the perforated site. He was discharged 8 d after the endoscopic closure without the need for surgical intervention. The meal was not the cause of the colon transversum perforation.

Core tip: The prompt and adequate management of post-operative gastrointestinal perforation is imperative. For delayed perforations, surgical management is the most common option. Herein we report a case of delayed colonic perforation that was successfully repaired by an endoscopic approach, even after the patient ingested food. We describe the techniques and highlight the importance of adequate bowel preparation for a favorable outcome.

- Citation: Inoki K, Sakamoto T, Sekiguchi M, Yamada M, Nakajima T, Matsuda T, Saito Y. Successful endoscopic closure of a colonic perforation one day after endoscopic mucosal resection of a lesion in the transverse colon. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(8): 238-242

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i8/238.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i8.238

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) is a relatively safe and basic technique with a reported risk of perforation of 0%-5%[1]. The 30-d mortality rate for perforation after colonoscopy, both therapeutic and diagnostic, has been reported to be 0%-26%[2]. As a result of developments in endoscopic techniques, endoscopic closure is a considerable option for the management of perforation during endoscopic treatments[3]. However, for delayed colorectal perforation, emergency surgery is often imperative[4]. Herein we report a case of delayed colonic perforation due to EMR that was successfully treated by endoscopic closure, even though the patient had already ingested one meal after the procedure.

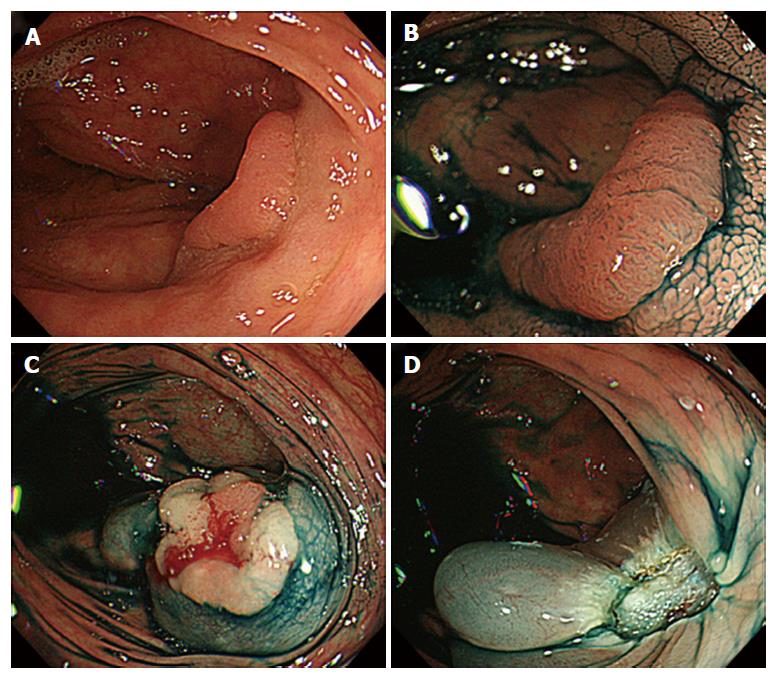

A 73-year-old man was referred to the National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, for the management of multiple polyps in the transverse and sigmoid colon, one of which was approximately 20 mm in size and was located in the transverse colon. Diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy was planned on the same day. Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was planned on the largest lesion, which was 18 mm in size and was diagnosed as adenoma, 0-IIa, laterally spreading tumor non-granular type (LST-NG) (Figure 1A and B). On the basis of these findings, we decided to proceed with EMR instead of ESD for the largest lesion (Figure 1C and D); the other smaller polyps were removed by polypectomy or biopsy. No clippings were performed after EMR. Total colonoscopy and all related procedures were performed using carbon dioxide insufflation. There were no immediate complications, and the patient was asymptomatic during the endoscopic procedure.

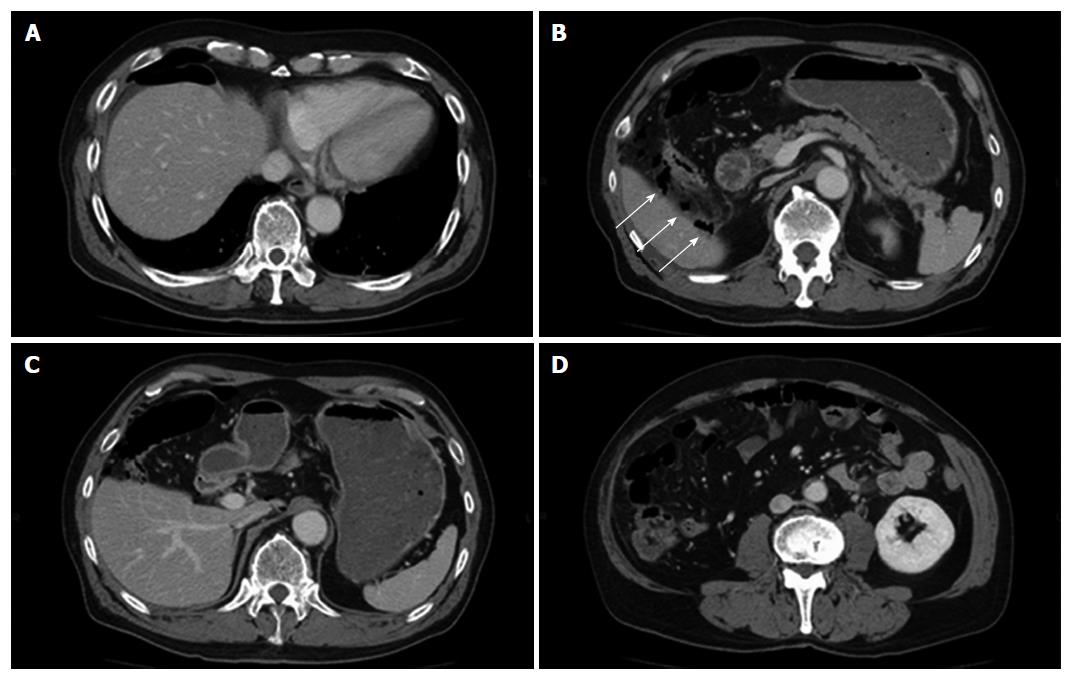

The day after the endoscopic treatment, his white blood cell count was noted to increase, but there was no fever. There were no abdominal symptoms in the morning, but he started to have severe right upper quadrant pain after having his first meal post-procedure. On physical examination, abdominal rigidity and mild tenderness on the right upper quadrant were observed. A computed tomography (CT) scan was immediately performed and showed free air around the right lobe of the liver and inside the adipose tissue surrounding the ascending colon. A small amount of ascites around the liver was also recognized (Figure 2A and B). He was diagnosed with post-EMR colonic perforation, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were immediately started. Prior to repair, the CT scan was reviewed, and the stomach was seen to be filled with food that had not yet reached the colon (Figure 2C and D). After discussion with the surgeons, a decision was made to perform endoscopic closure of the perforated site.

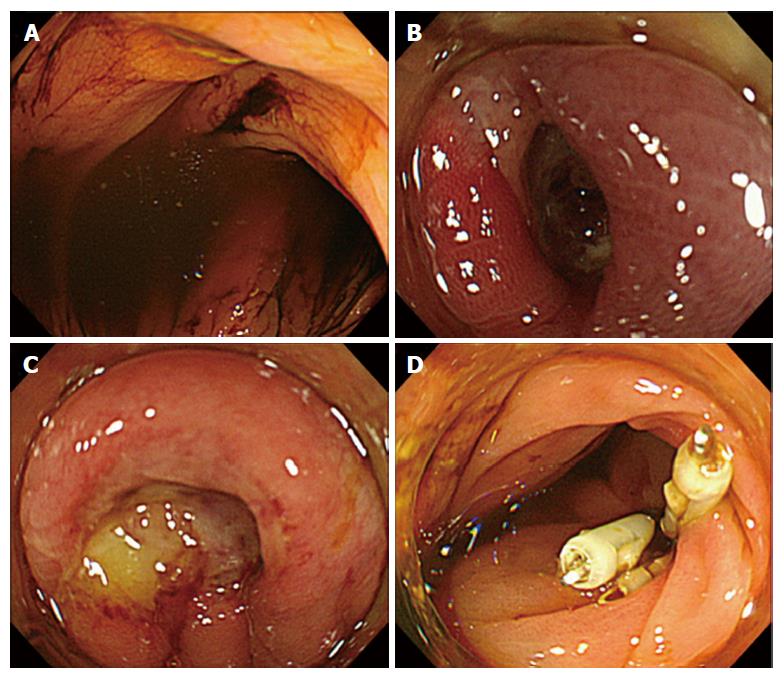

During colonoscopy, brown intestinal juice was observed, but there were no food residues (Figure 3A). The examination of the EMR site showed a reddish and edematous ulcer (Figure 3B), initially without an obvious perforation (Figure 3C). Nevertheless, we judged this as the perforated site and performed endoscopic closure using four clips (HX-610-090L; Olympus, Japan) (Figure 3D).

The day after the endoscopic closure, the patient had mild fever but no abdominal pain and a small amount of free air under the right diaphragm was seen on his chest X-ray. No fever was observed during the clinical course and white blood cell count (WBC) and C-reactive protein (CRP) declined after the endoscopic closure. Enteral feeding was resumed 5 d after the endoscopic treatment, and he was discharged eight days after the treatment.

Castellví et al[5] reported several factors that can be used to recommend conservative treatment, including endoscopic closure for colonic perforation. These factors are good general condition, unobvious perforation, early diagnosis, no signs of diffuse peritonitis, and proper colonic preparation. Our patient met all these factors.

Food is considered to adversely affect the management of a delayed perforation because it may contaminate the perforated site and peritoneal cavity leading to severe peritonitis. In the present case, we confirmed that the food in the stomach did not reach the EMR site. It has been reported that the small bowel transit time is approximately 3-5 h; by responding quickly, we successfully performed endoscopic closure before the food could contaminate the site.

Adequate bowel preparation is strongly associated with detection rates for adenoma and is regarded as an indicator of a good endoscopy examination[6]. A clean environment is also essential for safe colonoscopy, and inadequate bowel preparation is related to poor outcomes of perforation after colonoscopy. In fact, with inadequate bowel preparation, endoscopists cannot observe the perforated site and inflammation would be worse. At our institution, the bowel preparation regimen for colonic ESD cases is more meticulous than that for screening cases. For this case, a segment score 3 was given based on the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale[7].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of a successful repair of colonic perforation, even after starting a meal. It is important to confirm that food has not reached the perforated site and to immediately perform the closure.

Adequate bowel preparation is necessary for the success of colonic endoscopic closure after delayed perforation. Understanding risk factors, quick decision-making after a discussion with surgeons, and a prompt response are of prime importance.

A 73-year-old man with delayed colonic perforation that was successfully repaired by an endoscopic approach, even after the patient ingested food.

Delayed post-endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) intestinal perforation.

Peritonitis, postpolypectomy electrocoagulation syndrome.

Elevated white blood cell count and C-reactive protein declined gradually after the endoscopic closure.

Computed tomography showed free air around the right lobe of the liver and air density inside the adipose tissue around the ascending colon.

Well differentiated adenocarcinoma, low grade atypia.

Complete endoscopic closure of perforation site.

Basically emergent surgery is considered to be necessary for delayed post-EMR intestinal perforation; therefore, consulting surgeons is imperative.

EMR: Endoscopic mucosal resection; ESD: Endoscopic submucosal dissection; LST-NG: Laterally spreading tumor non-granular type.

Adequate bowel preparation is necessary for the success of colonic endoscopic closure after delayed perforation. Understanding factors to select conservative or surgical treatment, quick decision-making after a discussion with surgeons, and a prompt response are of prime importance.

This is a well-written manuscript describing an unusual case report and a promising alternative treatment.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Cattermole GN, Milone M, Tepes B S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang FF

| 1. | Repici A, Pellicano R, Strangio G, Danese S, Fagoonee S, Malesci A. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early colorectal neoplasia: pathologic basis, procedures, and outcomes. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1502-1515. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lohsiriwat V. Colonoscopic perforation: incidence, risk factors, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:425-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Orsoni P, Berdah S, Verrier C, Caamano A, Sastre B, Boutboul R, Grimaud JC, Picaud R. Colonic perforation due to colonoscopy: a retrospective study of 48 cases. Endoscopy. 1997;29:160-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isbister WH. The management of colorectal perforation and peritonitis. Aust N Z J Surg. 1997;67:804-808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Castellví J, Pi F, Sueiras A, Vallet J, Bollo J, Tomas A, Verge J, Caballero F, Iglesias C, De Castro J. Colonoscopic perforation: useful parameters for early diagnosis and conservative treatment. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2011;26:1183-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sherer EA, Imler TD, Imperiale TF. The effect of colonoscopy preparation quality on adenoma detection rates. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:545-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 924] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |