Published online Jul 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i7.191

Peer-review started: January 26, 2016

First decision: March 1, 2016

Revised: March 13, 2016

Accepted: May 10, 2016

Article in press: May 11, 2016

Published online: July 16, 2016

Processing time: 166 Days and 3.3 Hours

An otherwise healthy, full-term neonate presented at day 15 of life to the pediatric emergency with generalized papulo-pustular rash for 2 d. This was finally diagnosed as bullous impetigo caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). The skin lesions decreased significantly after starting antibiotic therapy and drainage of blister fluid. There was no recurrence of the lesions on follow-up. This case of generalized pustular eruption due to S. aureus in a neonate is reported, as it poses a diagnostic dilemma and can have serious consequences if left untreated.

Core tip: Pustular disorders are common in neonatal period. It is important to distinguish benign physiological rashes from significant pathological eruptions. A case of generalized pustular eruption due to Staphylococcus aureus in a neonate is reported. Such lesions can pose a diagnostic dilemma and have serious consequences if left untreated. Differential diagnosis of neonatal pustular lesions has been discussed and main features of each have been highlighted here.

- Citation: Duggal SD, Bharara T, Jena PP, Kumar A, Sharma A, Gur R, Chaudhary S. Staphylococcal bullous impetigo in a neonate. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(7): 191-194

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i7/191.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i7.191

Pustular disorders are common in the neonatal period, most of which are benign and self-limiting[1,2]. It is important to distinguish the benign physiological rashes from significant pathological pustular eruptions[3]. Similarity of clinical features, immaturity of neonatal skin and lack of relevant literature poses diagnostic difficulty in cases of neonatal pustular lesions[4]. Another practical problem relates to the process of ruling out an infectious etiology.

An otherwise healthy, full-term neonate presented at day 15 of life, to the pediatric emergency with generalized papulo-pustular lesions for 2 d. It was during the summer of year 2015. The neonate was born at a primary health centre following a full-term normal vaginal delivery and had been on breastfeed since birth. The mother gave no history of sexually transmitted infections or genital lesions and there was no history of similar complaints in other siblings. Informed consent was taken from the mother and the neonate was examined. On examination his general hygiene appeared to be poor. He weighed 2600 g, was active, showed no malaise, or irritability. The pustules were 15-20 in number, generalized in distribution, over scalp, neck, trunk and extremities sparing palms and soles. These were flaccid, non-tender bullous lesions with an erythematous base, measuring 1 to 2 cm in diameter (Figure 1). No scars or sinuses were present. These were provisionally diagnosed as viral eruptions and a call was sent to the Microbiology Department for opinion and necessary investigations. He was afebrile, had no lymphadenopathy, the neonatal reflexes and rest of the systemic examination was normal. All the pustules were punctured and dark yellowish purulent fluid was drained aseptically. This fluid was inoculated at the bedside on Chocolate agar, Blood agar and MacConkey agar plates and smears were prepared for direct Gram staining. The plates were streaked and incubated aerobically overnight at 37 °C. A tube of Brain Heart Infusion broth and a plate of Mannitol Salt Agar were also inoculated. Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed by Kirby-Bauer Disc diffusion method and the results were interpreted as per CLSI 2015 guidelines.

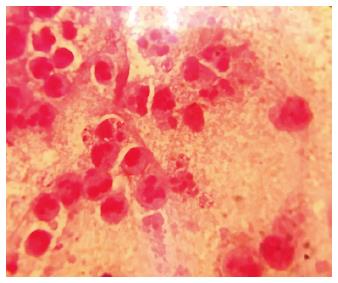

Direct Gram stain showed many pus cells and intracellular gram-positive cocci in clusters (Figure 2). Pure growth of pin-head, buff coloured, beta hemolytic colonies appeared on Blood agar after overnight incubation. The case was finally diagnosed as bullous impetigo caused by Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). The isolate was identified on the basis of Gram stain, golden yellow pigment, catalase test, coagulase (slide, tube) test and yellow colonies on Mannitol Salt Agar. It was found to be sensitive to penicillin, cefoxitin, clindamycin, gentamicin, and chloramphenicol but resistant to erythromycin and ciprofloxacin. Tzanck smear was negative. However blood culture of the neonate could not be performed. Human immunodeficiency virus serology and venereal diseases research laboratory test (for syphilis) of mother was negative. The patient was isolated and treatment was started with oral suspension of amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (30 mg/kg body weight divided every 12 h) along with topical mupirocin cream twice daily. The skin lesions decreased significantly after starting antibiotic therapy and drainage of blister fluid. No fresh lesions were seen and there was no recurrence of the lesions during his 7 d hospital stay. He was discharged with an advice to report back in case of recurrence. However, no further episode was reported.

Pustular eruptions pose a diagnostic dilemma during the neonatal period. Diagnosis depends upon clinical features along with few simple laboratory investigations. There are many different causes of neonatal pustular dermatosis including noninfectious and infectious causes[3-5] (Table 1). Ruling out an infective etiology remains the corner stone of any diagnostic approach in neonatal pustular eruptions. Early and accurate diagnosis can spare a healthy neonate with a benign treatable condition from unnecessary investigations and also prevent the occurrence of severe complications.

| Causes | Characteristic features |

| Infectious causes | |

| Herpes simplex virus | Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base that rupture to become erosions covered by crusts; may have prodromal symptoms |

| Varicella zoster virus | Lesions of different stages are present at the same time in a given body area as new crops develop |

| Streptococcus spp. | Similar lesions with Gram stain showing Gram positive cocci in chains. Further differentiated on the basis of culture characteristics and biochemical tests |

| Treponema pallidum | Diffuse erythematous lesions containing large number of treponemes. Associated systemic involvement |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | Cutaneous tenderness, positive Nikolsky sign, large areas of desquamation or exfoliation. Infection spreads hematogenously because of absence of protective antitoxin antibodies. Culture of bullae is negative |

| Cutaneous candidiasis | Generalized skin eruptions at birth, characterized by erythematous macules and papules Candida albicans demonstrated on direct KOH smear, skin biopsy |

| Listeriosis | Presents with systemic signs and symptoms of sepsis |

| Pseudomonas skin infection | These may present as localized cutaneous folliculitis or as necrotising infection, ecthyma gangrenosum. Lesions are painful and systemic involvement may be seen. Diagnosis is confirmed by isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from lesions |

| Noninfectious causes | |

| Bullous erythema multiforme | Usually involves extensor surfaces of extremities |

| Bullous lupus erythematosus | May be pruritic; tends to favor the upper part of the trunk and proximal upper extremities |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Vesicles and bullae appear rapidly on widespread pruritic, urticarial plaques |

| Pemphigus vulgaris | Healing with hyperpigmentation |

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome | Vesiculo-bullous disease of the skin, mouth, eyes, and genitalia; ulcerative stomatitis with hemorrhagic crusting is most characteristic feature |

| Toxic epidermal necrolysis | Stevens-Johnson–like mucous membrane disease followed by diffuse generalized detachment of the epidermis |

| Insect bites | Bullae seen with pruritic papules grouped mainly in exposed parts of body |

| Thermal burns | History of burn with blistering in second-degree burns |

| Neonatal pustular psoriasis | Sterile widespread pustules on an erythematous background |

| Erythema toxicum neonatorum | Benign self-limited eruption occurring in early neonatal period in healthy neonates. Macular erythema, papules, vesicles or pustules |

| Neonatal acne | Acneform eruptions in newborn often seen on nose and adjacent portions of cheek |

Incubation period of Staphylococcal skin and soft tissue infections vary from 2-10 d, thus, ruling out iatrogenic causes at the time of delivery in this case. In the present case probable source of S. aureus infection could be mother/other family members/fomites like dirty linen/clothes. The pathogenicity of S. aureus skin and soft tissue infections is related to various bacterial surface components and to extracellular proteins[6]. S. aureus can disrupt the skin barrier by secreting exfoliative toxins A and B. These act as superantigens to promote massive release of T-lymphocytes and lymphokines like IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α[7]. The exfoliative toxin A causes proteolytic cleavage of desmoglein-1 which is present in desmosomes and is responsible for cell-cell adhesion. This leads to blister formation just below the stratum corneum allowing bacteria in the blister fluid to proliferate and spread[8]. Depending on the immune status of the host, it may lead to formation of exfoliative cutaneous eruptions, vomiting, fall in blood pressure and shock as in staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome or may be localized to skin as bullous impetigo, as seen in the present case. There have been several case reports suggesting role of Panton Valentine leukocidin toxin in Staphylococcal skin infections; associated more commonly with MSSA than MRSA, particularly in community isolates[9].

In full-term newborns, S. aureus infection usually first appears as a skin and soft tissue infection, but may rapidly progress to osteomyelitis and pneumonia[4]. Rarely these skin and soft tissue infections may invade dermal and fascial barriers to cause S. aureus bacteremia[10]. Blebs should be punctured as soon as formed and topical ointment/lotion should be applied[11]. Full recovery usually occurs in 2-3 wk. Isolation of the patient is recommended as an infection control measure otherwise it may rapidly spread to other patients, attendants and health care workers.

The main objective of this article was to emphasize a systematic approach in evaluation of pustular eruptions in the neonate. A detailed perinatal history; complete physical examination; and careful assessment of the morphology and distribution of the lesions form the cornerstone for diagnosis. Targeted therapy can reduce the morbidity and mortality; and associated hospitalization costs.

A full-term neonate presented at day 15 of life, to the pediatric emergency with generalized papulo-pustular lesions for 2 d.

Neonatal pustulosis.

Infectious causes like Herpes simplex virus, Varicella zoster virus, Streptococcus spp., non-infectious causes include bullous erythema multiforme, bullous lupus erythematosus, bullous pemphigoid.

All the pustules were punctured and fluid was cultured. Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed by Kirby-Bauer Disc diffusion method and the results were interpreted as per CLSI 2015 guidelines.

Direct Gram stain showed many pus cells and intracellular gram-positive cocci in clusters. Culture grew Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus).

Complete resolution of lesions after treatment with oral amoxicillin and clavulanic acid along with topical mupirocin cream.

In full-term newborns, S. aureus infection usually first appears as a skin and soft tissue infection, but may rapidly progress to osteomyelitis and pneumonia or cause bacteremia. Blebs should be punctured as soon as formed and topical ointment/lotion should be applied. Full recovery usually occurs in 2-3 wk. Isolation of the patient is recommended as an infection control measure.

Pustules are small pus filled blisters in the superficial layers of skin.

(1) Pustular eruptions in neonates pose a diagnostic dilemma; (2) Diagnosis depends upon clinical features along with few simple laboratory investigations; (3) A detailed perinatal history; complete physical examination; and careful assessment of the morphology and distribution of the lesions form the cornerstone for diagnosis; (4) Targeted therapy can reduce the morbidity and mortality; and associated hospitalization costs.

The paper is well written. The case is interesting and clearly reported.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

P- Reviewer: Gao SH, Hu SCS, Negosanti L S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Van Praag MC, Van Rooij RW, Folkers E, Spritzer R, Menke HE, Oranje AP. Diagnosis and treatment of pustular disorders in the neonate. Pediatr Dermatol. 1997;14:131-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baruah CM, Bhat V, Bhargava R, Garg RB, Kumar V. Prevalence of dermatoses in the neonates in Pondichery. Indian J Der Ven Lepl. 1991;57:25-28. |

| 3. | Ghosh S. Neonatal pustular dermatosis: an overview. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nanda S, Reddy BS, Ramji S, Pandhi D. Analytical study of pustular eruptions in neonates. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:210-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cole C, Gazewood J. Diagnosis and treatment of impetigo. Am Fam Physician. 2007;75:859-864. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Archer GL. Staphylococcus aureus: a well-armed pathogen. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:1179-1181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Manders SM. Toxin-mediated streptococcal and staphylococcal disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:383-398; quiz 399-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Amagai M, Matsuyoshi N, Wang ZH, Andl C, Stanley JR. Toxin in bullous impetigo and staphylococcal scalded-skin syndrome targets desmoglein 1. Nat Med. 2000;6:1275-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lina G, Piémont Y, Godail-Gamot F, Bes M, Peter MO, Gauduchon V, Vandenesch F, Etienne J. Involvement of Panton-Valentine leukocidin-producing Staphylococcus aureus in primary skin infections and pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:1128-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1788] [Cited by in RCA: 1824] [Article Influence: 70.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rongpharpi SR, Duggal S, Kalita H, Duggal AK. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: targeting the source. Postgrad Med. 2014;126:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Soellner CH. Pemphigus neonatorum. Ame J Nurs. 1922;23:94-98. |