Published online Dec 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i12.390

Peer-review started: June 29, 2016

First decision: September 5, 2016

Revised: September 26, 2016

Accepted: October 22, 2016

Article in press: October 24, 2016

Published online: December 16, 2016

Processing time: 164 Days and 8.2 Hours

Drug-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation is uncommon. Including the patient described in this report, chemotherapy-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation has only been described in ten individuals. This paper describes the features of a woman with recurrent and metastatic breast cancer who developed paclitaxel-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation and reviews the characteristics of other oncology patients who developed reticulate hyperpigmentation from their antineoplastic treatment. A 55-year-old Taiwanese woman who developed reticulate hyperpigmentation on her abdomen, back and extremities after receiving her initial treatment for metastatic breast cancer with paclitaxel is described. The hyperpigmentation became darker with each subsequent administration of paclitaxel. The drug was discontinued after five courses and the pigment faded within two months. PubMed was searched with the key words: Breast, cancer, chemotherapy, hyperpigmentation, neoplasm, reticulate, tumor, paclitaxel, taxol. The papers generated by the search, and their references, were reviewed. Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation has been described in four men and six women. Bleomycin, cytoxan, 5-fluorouracil, idarubacin, and paclitaxel caused the hyperpigmentation. The hyperpigmentation faded in 83% of the patients between two to six months after the associated antineoplastic agent was discontinued. In conclusion, chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation is a rare reaction that may occur during treatment with various antineoplastic agents. The hyperpigmentation fades in most individuals once the treatment is discontinued. Therefore, cancer treatment with the associated drug can be continued in patients who experience this cutaneous adverse event.

Core tip: Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation has been described in four men and six women being treated for either a hematologic malignancy or a solid tumor. Associated drugs included cytoxan (with or without idarubicin), paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil and bleomycin. The skin lesions were usually asymptomatic and appeared as linear macular hyperpigmention that was lacy, net-like, or both on the patient’s back. The hyperpigmentation appeared within 3 d to 18 wk after starting the drug and faded within 2 to 6 mo after stopping the medication. Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation did not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the associated antineoplastic treatment.

- Citation: Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation: Report and review of chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(12): 390-400

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i12/390.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i12.390

Reticulate pigmentary disorders can be congenital or acquired[1]. Drug-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation is uncommon[2]. A woman with paclitaxel-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation is described and antineoplastic therapy-related linear and reticulate hyperpigmentation is reviewed.

A 55-year-old Taiwanese woman with metastatic breast cancer to her lungs and bones presented for evaluation of a new asymptomatic rash on her abdomen, back and legs. She had a prior allergic reaction, in 2014, to zoledronic acid after the initial intravenous infusion; non-tender, non-pruritic erythematous patches developed on her proximal medial thighs and inguinal regions, axilla, antecubital fossa and popliteal fossa. The lesions resolved spontaneously and there was no reaction when an alternative agent, denasumab, was given.

In 2004, she was diagnosed with invasive mixed ductal and lobular carcinoma (grade 2, T3N3 with lymphatic vessel invasion, estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor negative, and HER2/neu negative) right breast cancer. Treatment included right breast lumpectomy, chemotherapy (adriamycin and cytoxan, followed by taxol), radiation therapy, and hormonal therapy (for five years); her treatment finished in February 2010.

Follow up workup in July 2014 revealed biopsy-confirmed recurrence of her breast cancer characterized by hilar adenopathy, multiple pulmonary nodules and bony metastases. She began daily letrozole that month.

Restaging, in May 2015 showed disease progression. During the next few months, she was unsuccessfully treated initially with an oral selective estrogen receptor degrader and subsequently with a combination of abemaciclib, exemestane and everolimus. Capecitabine was started in September 2015; erythema appeared on the sun-exposed areas of her face. Subsequently, diffuse and confluent malar postinflammatory hyperpigmentation developed. Increased tumor burden was observed after 4 mo of treatment and the drug was discontinued.

Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) intravenous weekly therapy was initiated in January 2016. She was premeditated prior to each treatment to prevent hypersensitivity reactions. She received intravenous dexamethasone (10 mg) and famotidine (20 mg) and intramuscular diphenhydramine (25 mg).

Hyperpigmentation on her abdomen, back and extremities was noted to initially appear during the week after receiving her first infusion of paclitaxel and prior to her second treatment. She also noted that the new hyperpigmentation appeared darker (and provided greater contrast with the normal appearing skin of her abdominal striae) on the day of each paclitaxel infusion. In contrast, her facial hyperpigmentation-secondary to capecitabine - was fading.

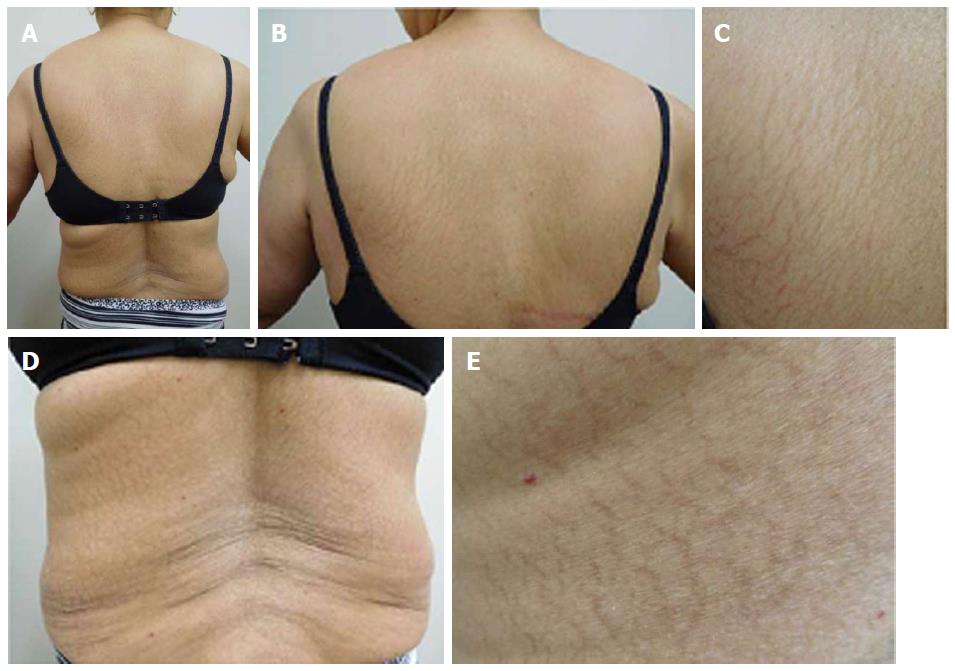

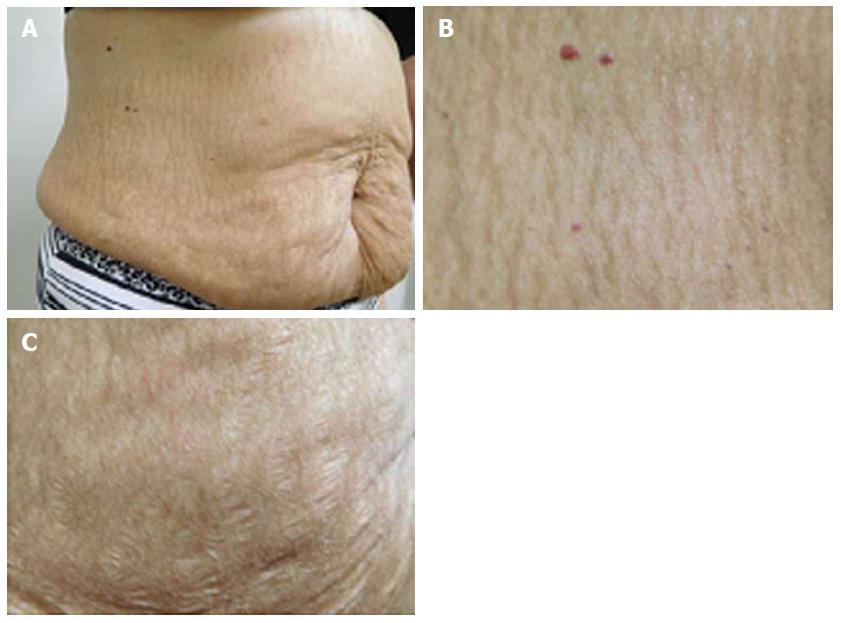

She was examined after her fifth weekly treatment of paclitaxel. She had dark brown linear and reticulate hyperpigmentation, more prominent proximally than distally, on the extensor arms (Figure 1) and legs (Figure 2), on the back (Figure 3), and on the abdomen (Figure 4). The net-like hyperpigmentation did not occur in the abdominal striae (Figure 4).

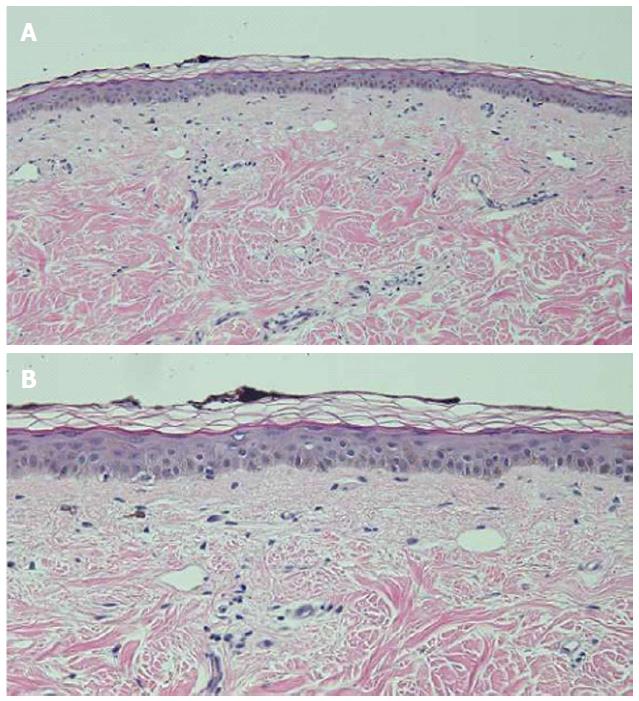

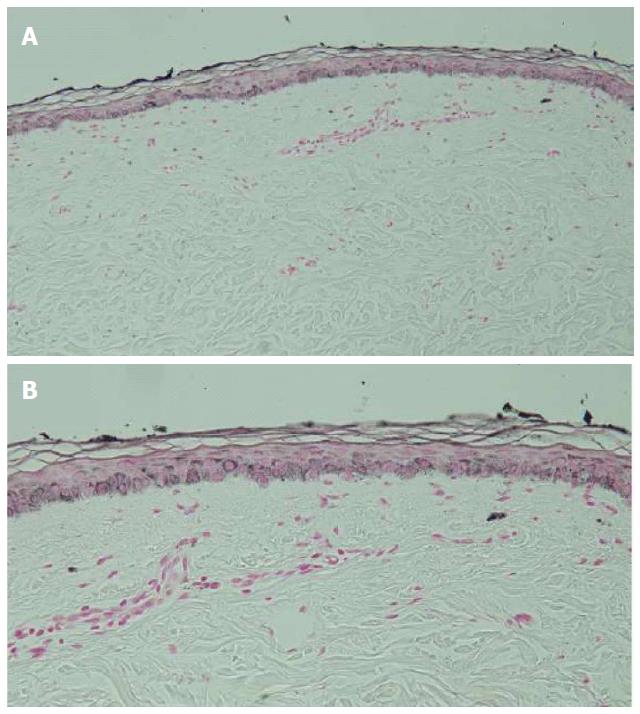

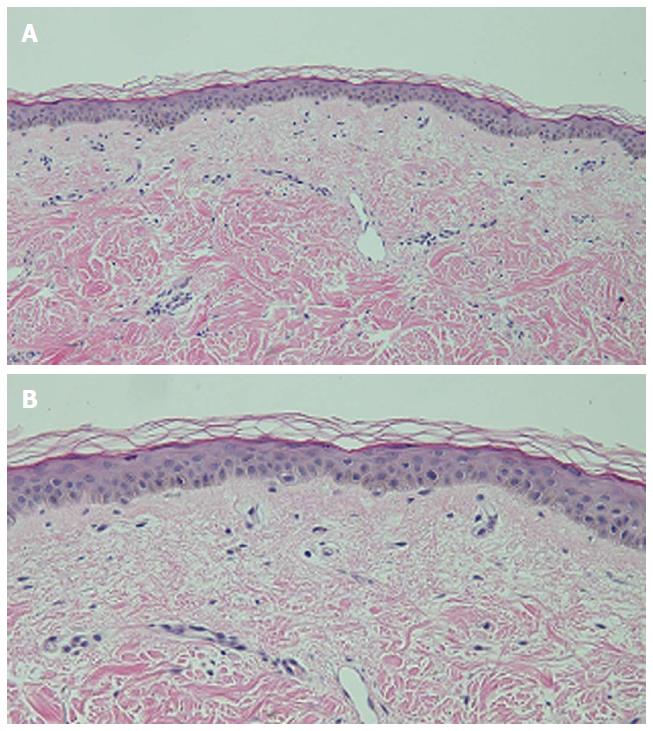

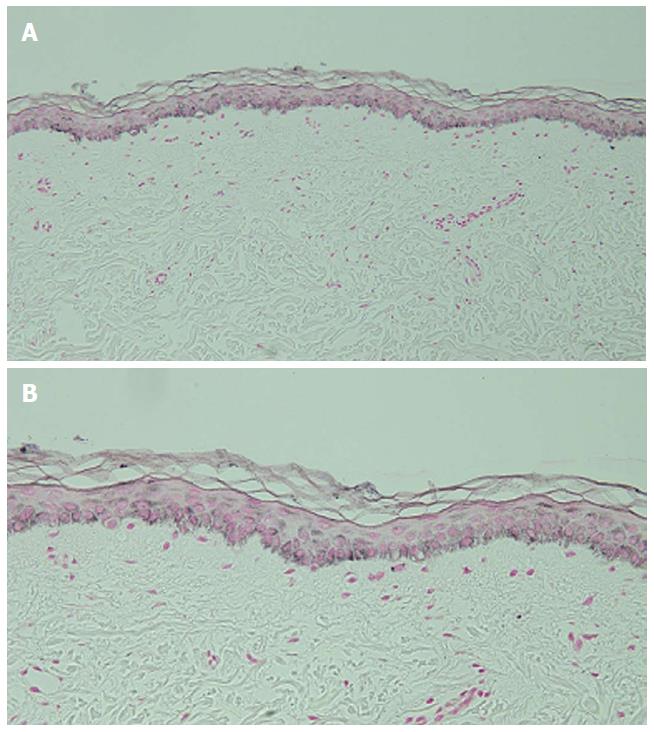

Microscopic examination of hyperpigmented skin and normal appearing skin (for comparison) from the abdomen was performed. The hyperpigmented skin showed not only prominent melanin deposited within the basal layer of the epidermis but also incontinence of melanin pigment and melanophages in the upper dermis (Figure 5); a Fontana-Masson stain confirms the presence of melanin at these locations (Figure 6). In contrast, the normal-appearing skin only showed slight hyperpigmentation of the epidermal basal layer (Figure 7); a Fontana-Masson stain confirmed the sparse presence of melanin in the basal layer of the epidermis and focally in the papillary dermis (Figure 8). A Perl’s iron stain, to detect iron, was negative in both the hyperpigmented skin and the normal appearing skin.

In summary, in comparison to the normal-appearing skin, the deposition of melanin in the epidermis and dermis was significantly greater in the areas of hyperpigmentation.

She received two additional courses of paclitaxel. After her seventh treatment, she developed painful and swollen, erythematous scaling plaques on her wrists, posterior neck and right ankle (Figure 9). The right ankle lesion progressed and a similar lesion appeared on her left ankle (Figure 10). Biopsy demonstrated an interface dermatitis. Her ankle lesions prevented her from being able to walk; therefore, her paclitaxel treatments were discontinued. Her symptoms and skin changes completely resolved.

The reticulate hyperpigmentation had completely faded on her abdomen and legs at follow up 2 mo after stopping the paclitaxel. There was also significant fading of the pigmentation on her back and arms. She is currently being treated with a monthly infusion of faslodex and palbociclib daily for 3 consecutive weeks each month and has not developed chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation.

Widespread reticulate hyperpigmentation has, albeit rarely, been observed following exposure to medications[2]. Reticulate hyperpigmentation has been described in single individuals who have received topical benzoyl peroxide[3], oral diltiazim[4], or intravenous regional anesthesia with prilocaine and methylprednisolone[5]. This pattern of hyperpigmentation has also been observed in individuals receiving antineoplastic therapy.

PubMed was used to search the following terms: Breast, cancer, chemotherapy, hyperpigmentation, neoplasm, reticulate, tumor, paclitaxel, taxol. All papers were reviewed and relevant manuscripts, along with their reference citations, were evaluated. Including the patient reported in this paper, chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation has occurred in 10 individuals (Table 1)[6-9].

| Case | Age (yr) Race Sex | Chemo | Onset (d) | OCF | Site | Histo | Cancer | Seq | Ref. |

| 1 | 55 NR M | Adria Bleo1 Cyclo MTX Vin | 42 | None | Arms Back Legs2 | DM MBaK MSBaK EM3 | NHL | Persists | 6 |

| 2 | 61 Ca M | 5-FU14 | 3 | CAE | Back2 | NR | GIT | Faded5 | 7 |

| 3 | 64 Ca M | Cyt1 Ida1 Lo | 21 | None | Back Butt | NR | AML | UK | 8C5 |

| 4 | 74 Ca M | Cyclo Cyt1 Dexa Ida1 Vin | 28 | Mild Pru | Back Shdr | MBaK MPaD PI | ALL | Faded6 | 8C2 |

| 5 | 49 Ca W | Pac1 | 126 | None | Back Thi | MBaK MPaD PI | BC | Faded7 | 8C1 |

| 6 | 51 NR W | Cyt1 Ida1 | > 28 | None | Back (low) | NR | AML | NR | 9C2 |

| 7 | 55 Ta W | Pac1 | < 7 | None | Abd Back Legs | DM MBaK PI | BC8 | Faded9 | CR |

| 8 | 61 Ca W | Cyt1 Top | 28 | None | Back Butt Thi | RCM10 | AML | UK | 8C4 |

| 9 | 63 NR W | Carbo 5-FU1 | 311 | PAE | Back Butt Thi | NR | MEC | NR | 9C1 |

| 10 | 74 Ca W | Carbo Pac1 | 42 | PAE Pru | Back | RCM10 | OC | Faded12 | 8C3 |

Wright et al[6] initially described reticulate hyperpigmentation resulting from chemotherapy in 1990. Their patient was a 55-year-old man with non-Hodkins lymphoma who “developed striking hyperpigmentation of the skin, consisting of widespread symmetrical reticulate streaks of hyperpigmentation in a racemose pattern on the trunk and limbs”. He had received several antineoplastic agents, including bleomycin; the hyperpigmentation developed after 6 wk of treatment and a total dose of 75 mg of bleomycin[6].

Five years later, in 1995, Allen et al[7] reported a 61-year-old man with metastatic cancer from a bowel primary who “developed an asymptomatic eruption consisting of widespread reticulate erythema and pigmentation” one day after finishing a 48 h intravenous infusion of 680 mg (400 mg/m2) of 5-fluorouracil. His next 5-fluorouracil treatment, three weeks later at half the dose, did not result in recurrence of the eruption. Neither the erythema nor the hyperpigmentation recurred during subsequent treatments at full dose and the hyperpigmentation gradually faded over a period of 16 wk[7].

A decade would pass before the next descriptions of chemotherapy-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation by Jogi et al[9]. The first patient reported by the investigators was a 63-year-old woman with mucoid epidermoid carcinoma of the parotic gland who was receiving concomitant chemoradiotherapy; three days into her third cycle, which consisted of carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil, she developed a reticulated erythematous rash on her back and legs. The erythema eventually changed first to a violaceous and then to a brownish discoloration. During her fourth cycle she was noted to have a reticulated, hyperpigmented macular eruption on her back, posterior thighs, and popliteal fossa[9].

The second patient reported by Jogi et al[9] in 2005 was a 51-year-old woman with acute myelogenous leukemia. She had received induction chemotherapy with cytarabine and idarubicin. More than four weeks later, when she returned for a bone marrow biopsy, “she was found to have reticulated hyperpigmented patches on her lower back[9]”.

More recently, after another decade, in 2015 Masson Regnault et al[8] described chemotherapy-related reticulated hyperpigmentation in five oncology patients. Their case series included two men with leukemia, and three women with breast cancer, leukemia, or ovarian carcinoma. The implicated antineoplastic agents-received either alone or concurrently-were cytarabine, idarubicin, and paclitaxel[8].

A reliable and valid method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions was established by Naranjo et al[10] in 1981. The current report describes a woman with metastatic breast cancer. In this patient, chemotherapy-associated reticulate hyperpigmentation developing as an adverse drug reaction induced by paclitaxel would be assigned to a definite probability category according to Naranjo et al[10]’s adverse drug reaction probability scale (Table 2).

| Question | PA | PS |

| Are there previous conclusive reports on this reaction? | Yes | 1 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Did the adverse event appear after the suspected drug was administered? | Yes | 2 |

| Answer score: Yes = +2; No = -1 | ||

| Did the adverse reaction improve when the drug was discontinued or a specific antagonist was administered? | Yes | 1 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Did the adverse reaction reappear when the drug was readministered? | Yes | 2 |

| Answer score: Yes = +2; No = -1 | ||

| Are there alternative causes (other than the drug) that could on their own have caused the reaction? | No | 2 |

| Answer score: Yes = -1; No = +2 | ||

| Did the reaction reappear when a placebo was given? | DNK | 0 |

| Answer score: Yes = -1; No = +1 | ||

| Was the drug detected in the blood (or other fluids) in concentrations known to be toxic? | DNK | 0 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Was the reaction more severe when the dose was increased, or less severe when the dose was decreased? | DNK | 0 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Did the patient have a similar reaction to the same or similar drugs in any previous exposure? | DNK | 0 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Was the adverse event confirmed by any objective evidence? | Yes | 1 |

| Answer score: Yes = +1; No = 0 | ||

| Total score | 9 |

In summary, four men and six women with chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation have been described; the oncology patients ranged from 49 years to 74 years (median = 61 years). The men ranged in age from 55 years to 74 years (median = 63 years). The women ranged in age from 49 years to 74 years (median = 58 years).

Most of the individuals were Caucasian (6/7, 86%). One woman was Taiwanese. The race was not provided for 3 individuals.

Reticulate hyperpigmentation occurred in five patients with hematopoietic malignancies and five individuals with solid tumors. Acute myelogenous leukemia was the most common cancer (3 patients); other lymphoproliferative disorders included acute lymphoblastic leukemia and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Breast cancer was the underlying neoplasm in two women; other metastatic solid tumors, each in one patient, were gastrointestinal tract cancer, mucoid epidermoid carcinoma of the parotid gland, and ovarian carcinoma.

The patients were receiving between one (3 individuals, 30%) to five (2 individuals, 20%) antineoplastic agents. Four patients (40%) were receiving two drugs and one person (10%) was receiving three medications. For all individuals, either one agent (seven patients) or two drugs-cytoxan and idarubicin - (three patients) were considered to be the cause of the hyperpigmentation.

Reticulate hyperpigmentation was associated with Cytoxan-either alone (in one individual) or concurrent with idarubicin (in three patients). Paclitaxel was the causative agent in three women. Two patients’ reticulate hyperpigmentation was related to 5-fluorouracil; bleomycin was the implicated drug in one man.

Paclitaxel is a taxane. It is derived from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). Paclitaxel acts by stabilizing microtubules; this action not only promotes the assembly of tubulin but also prevents the depolymerization of formed polymers. Subsequently, microtubule bundles accumulate and cell death occurs since cell division is interrupted[11-14].

Paclitaxel is used not only in the management of breast cancer, but also other cancers, such as lung and ovary[11-15]. Cutaneous adverse effects of paclitaxel (and nab-paclitaxel) include alopecia, erythema multiforme, hand-foot syndrome (acral erythema), hypersensitivity reaction, mucositis, nail changes, photosensitivity reactions, and subacute lupus erythematosus[15-22]. In addition to the woman with metastatic breast cancer described in this report, paclitaxel-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation occurred in another woman with metastatic breast cancer and a woman with metastatic ovarian cancer.

The onset of reticulate hyperpigmentation following initiation of the associated chemotherapy ranged from 3 d to 18 wk (median = 28 d). Both patients receiving 5-fluorouracil has the most rapid onset of hyperpigmentation. The appearance of hyperpigmentation in women receiving paclitaxel ranged from less than 7 d in the currently described patient to 126 d in another women with breast cancer; the third woman receiving paclitaxel for ovarian cancer developed hyperpigmentation after 6 wk of treatment.

Associated pruritus or erythema or both were described in 40% (4/10 patients) of the individuals with chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation. Asymptomatic erythema was noted in two patients who had received 5-fluorouracil (one man and one woman) and one woman who had been treated with paclitaxel; the paclitaxel treated woman also had pruritus. Another man who was treated with cytarabine and idarubicin also had mild pruritus.

Chemotherapy-related reticulate hyperpigmentation appears as brown colored macular hyperpigmentation without scaling or other epidermal change that is linear, lacy and/or net-like. It was located on the back of all 10 patients. It was also present on the legs (5 patients), the buttocks (3 patients), the shoulders (2 patients) and the abdomen (1 patient). In the reported patient, the hyperpigmentation was not only on her back, but also on her anterior thighs and abdomen; the pigmentation on her abdomen spared her striae.

Microscopic examination was performed in only four patients[6,8]. Common histologic features in all of these individuals included increased melanin in the basal layer of the epidermis and melanophages in the papillary dermis. Increased melanin in the suprabasilar keratinocytes was observed in one patient[6], and melanin pigment incontinence into the upper dermis was noted in three patients[8]. These pathologic changes are similar to those that have been observed in patients with pigment changes from other chemotherapies[8].

Dermoscopy analysis was conducted in a 61-year-old woman with acute myelogenous leukemia. Her reticulate hyperpigmentation appeared 4 wk after treatment with cytarabine and a topoisomerase II inhibitor and showed a hyperpigmented reticulate network; reflectance confocal microscopy of the lesions demonstrated an increased amount of pigment in the basal layer of the epidermis[8]. Reflectance confocal microscopy was also performed in a 74-year-old woman with ovarian carcinoma; 6 wk after receiving paclitaxel and carboplatin, her hyperpigmentation appeared and showed increased content of melanin in basal keratinocytes[8].

Electron microscopy studies were performed in one patient-the 55-year-old man with non-Hodgkin lymphoma who received not only bleomycin, but also adriamycin, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and vincristine. His reticulate hyperpigmentation showed both a marked increase of singly arranged melanosomes in the basal keratinocytes and lipid vacuoles (along with damage to subcellular organelles) in not only the basal keratinocytes but also the melanocytes. In the upper papillary dermis, melanosomal complexes were found in endothelial cells and macrophages[6].

The pathogenesis of chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation remains to be established. All of the previous investigators-based on dermoscopy, confocal reflectance microscopy, pathology, and electron microscopy findings-hypothesize that the hyperpigmentation results from a secondary increase in melanogenesis caused by a direct toxic effect of the chemotherapy on the melanocytes[6-9]. Masson Regnault et al[8] also suggest that, in susceptible individuals, local changes in blood flow may partially account for the lesions being located in areas of contact, such as the back and buttocks.

The reticulate hyperpigmentation persisted while the patients continued to receive the associated antineoplastic agent. Subsequent follow-up was provided for 6 individuals. The hyperpigmentation partially or completed resolved in 83% (5/6) of the patients after the chemotherapy has been discontinued. Fading occurred within 2 to 6 mo.

Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation is a cutaneous reaction that has been described in ten individuals: Four men and six women. The patients were being treated for hematologic malignancies [acute myelogenous leukemia (3 patients), acute lymphoblastic leukemia (1 patient) and non-Hodgkins lymphoma (1 patient)] or solid tumors [breast cancer (2 patients), gastrointestinal carcinoma (1 patient) mucoid epidermal carcinoma of the parotid gland (1 patient) and ovarian cancer (1 patient)]. Cytoxan [alone (1 patient) or concurrent with idarubicin (3 patients)] was the most commonly associated drug. Other causative antineoplastic agents included paclitaxel (3 patients), 5-fluorouracil (2 patients) and bleomycin (1 patient). The skin lesions were asymptomatic in most of the oncology patients; pruritus, erythema, or both were noted in four individuals. The linear macular hyperpigmention was lacy, net-like, or both. It appeared on the back of all patients; other sites included the legs (5 patients), buttocks (3 patients), shoulders (2 patients) and abdomen (1 patient). The hyperpigmentation appeared within 3 d to 18 wk after starting the drug and faded within 2 to 6 mo after stopping the medication. Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation does not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the associated antineoplastic treatment.

A woman with metastatic breast cancer developed a new asymptomatic rash on her abdomen, back and legs after beginning intravenous weekly therapy with paclitaxel.

The patient’s paclitaxel-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation presented as dark brown linear and net-like hyperpigmentation on the extensor arms and legs, on the back, and on the abdomen with sparing of the abdominal striae.

The clinical differential diagnosis of the patient’s chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation includes cutis marmorata, erythema ab igne, livedo reticularis, and vasculitis.

Laboratory studies - including complete blood cell counts with platelets and serum chemistries - were normal.

Imaging studies - including computerized axial tomography scans and positron emission tomography scans - confirmed the presence of metastatic breast cancer in the patient’s lungs and bones.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of a biopsy from the hyperpigmented skin showed deposits of melanin within the basal layer of the epidermis in addition to incontinence of melanin pigment and melanophages in the upper dermis; Fontana-Masson stained sections confirmed the presence of melanin at these locations.

The patient’s chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation had either completely (on her abdomen and legs) or significantly (on her back and arms) faded by 2 mo after stopping the paclitaxel.

Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation has been described in four men and six women. Five patients had hematopoietic malignancies and five individuals had solid tumors. Reticulate hyperpigmentation was associated with Cytoxan-either alone or concurrent with idarubicin, paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil or bleomycin.

Reticulate hyperpigmentation refers to the pattern of linear and flat darkening of the skin being either net-like or lacy or both.

Chemotherapy-induced reticulate hyperpigmentation is a morphologically distinctive and clinically benign cutaneous reaction to various antineoplastic agents in oncology patients with either hematologic malignancies or solid tumors that does not require dose reduction or discontinuation of the associated antineoplastic treatment and typically resolves or fades spontaneously within 2 to 6 mo after stopping the medication.

This manuscript reported a case pigmentation after treatment with paclitaxel. The author also reviewed the literature on this phenotype, and provided some pathological examination of the pigmentation area. The manuscript is well written and is worthy of publication.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Fang BL, Higa GM, Hakenberg OW, Sugawara I, Shimoyama S, Takahashi T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Sardana K, Goel K, Chugh S. Reticulate pigmentary disorders. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79:17-29. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Zhang X, Khimji I, Gurkan UA, Safaee H, Catalano PN, Keles HO, Kayaalp E, Demirci U. Lensless imaging for simultaneous microfluidic sperm monitoring and sorting. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2535-2540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Weinberg JM, Moss T, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC. Reticulate hyperpigmentation of the skin after topical application of benzoyl peroxide. Acta Derm Venereol. 1998;78:301-302. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Jaka A, López-Pestaña A, Tuneu A, Lobo C, López-Núñez M, Ormaechea N. Letter: Photodistributed reticulated hyperpigmentation related to diltiazem. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:14. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Patel AN, Perkins W, Ravenscroft A, Varma S. Extraordinary reticulate hyperpigmentation occurring after Bier block. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:94-95. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Wright AL, Bleehen SS, Champion AE. Reticulate pigmentation due to bleomycin: light- and electron-microscopic studies. Dermatologica. 1990;180:255-257. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Allen BJ, Parker D, Wright AL. Reticulate pigmentation due to 5-fluorouracil. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:219-220. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Masson Regnault M, Gadaud N, Boulinguez S, Tournier E, Lamant L, Gladieff L, Roche H, Guenounou S, Recher C, Sibaud V. Chemotherapy-Related Reticulate Hyperpigmentation: A Case Series and Review of the Literature. Dermatology. 2015;231:312-318. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Jogi R, Garman M, Pielop J, Orengo I, Hsu S. Reticulate Hyperpigmentation secondary to 5-fluorouracil and idarubicin. J Drugs Dermatol. 2005;4:652-656. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, Domecq C, Greenblatt DJ. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:239-245. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Bachegowda LS, Makower DF, Sparano JA. Taxanes: impact on breast cancer therapy. Anticancer Drugs. 2014;25:512-521. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Binder S. Evolution of taxanes in the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2013;17 Suppl:9-14. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Gradishar WJ. Taxanes for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2012;6:159-171. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Pazdur R, Kudelka AP, Kavanagh JJ, Cohen PR, Raber MN. The taxoids: paclitaxel (Taxol) and docetaxel (Taxotere). Cancer Treat Rev. 1993;19:351-386. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Donati A, Castro LG. Cutaneous adverse reactions to chemotherapy with taxanes: the dermatologist’s point of view. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:755-758. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Payne AS, James WD, Weiss RB. Dermatologic toxicity of chemotherapeutic agents. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:86-97. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Reyes-Habito CM, Roh EK. Cutaneous reactions to chemotherapeutic drugs and targeted therapies for cancer: part I. Conventional chemotherapeutic drugs. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:203.e1-203.e12; quiz 215-216. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: An update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:545-570. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Payne JY, Holmes F, Cohen PR, Gagel R, Buzdar A, Dhingra K. Paclitaxel: severe mucocutaneous toxicity in a patient with hyperbilirubinemia. South Med J. 1996;89:542-545. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Cohen PR. Photodistributed erythema multiforme: paclitaxel-related, photosensitive conditions in patients with cancer. J Drugs Dermatol. 2009;8:61-64. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Paul LJ, Cohen PR. Paclitaxel-associated subungual pyogenic granuloma: report in a patient with breast cancer receiving paclitaxel and review of drug-induced pyogenic granulomas adjacent to and beneath the nail. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:262-268. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Beutler BD, Cohen PR. Nab-paclitaxel-associated photosensitivity: report in a woman with non-small cell lung cancer and review of taxane-related photodermatoses. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2015;5:121-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |