Published online Nov 16, 2016. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v4.i11.380

Peer-review started: April 12, 2016

First decision: May 19, 2016

Revised: May 31, 2016

Accepted: September 21, 2016

Article in press: September 22, 2016

Published online: November 16, 2016

Processing time: 216 Days and 21.8 Hours

Tension chylothorax following blunt thoracic trauma is an extremely rare condition. Here we report such a case and review its management. A 31-year-old man was involved in a road traffic collision. The car rolled over and the patient was ejected from the vehicle. On arrival at the Emergency Department the patient was conscious and haemodynamically stable. Clinical examination of the chest and abdomen was normal. The patient had sustained fractures of the sixth cervical vertebra and the tenth thoracic vertebra, left pleural effusion, haematoma around the descending aorta and fracture of the right clavicle. The left pleural effusion continued to increase in size and caused displacement of the trachea and mediastinum to the opposite side. An intercostal chest tube was inserted on the left side on the second day. It drained 1500 mL of milky, blood-stained fluid. We confirmed the diagnosis of chylothorax by a histopathological examination of a cell block prepared from the left pleural effusion using Oil red O stain. The patient was managed conservatively with chest tube drainage and fat free diet. The chylothorax completely resolved on the eighth day after the injury. The patient was discharged home on day 16.

Core tip: Tension chylothorax is an extremely rare complication of blunt chest trauma because the thoracic duct is well protected within the chest cavity. When chyle accumulates in the pleural cavity, it may cause cardiovascular, respiratory, or nutritional, complications. Here we report a patient who had tension chylothorax following blunt chest trauma and review its management.

- Citation: Idris K, Sebastian M, Hefny AF, Khan NH, Abu-Zidan FM. Blunt traumatic tension chylothorax: Case report and mini-review of the literature. World J Clin Cases 2016; 4(11): 380-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v4/i11/380.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v4.i11.380

Chylothorax is usually caused by an iatrogenic injury to the thoracic duct during thoracic surgery or as a complication of malignancy[1]. It is an extremely rare complication of blunt chest trauma[2]. In our hospital, we admit around one thousand blunt trauma patients every year, 18% of whom have chest trauma[3]. During the last fifteen years, we have encountered only a single case of blunt traumatic chylothorax. Chylothorax is caused by an injury of the thoracic duct which is well protected inside the chest. This explains the rarity of this condition. It may be associated with spine injuries[4-6]. When chyle accumulates in the pleural cavity, it may cause cardiovascular, respiratory, or nutritional complications[5]. The adverse effects of chylothorax depend on the size of the leak, associated co-morbidities and management of the patient. Here we report a case of tension chylothorax following blunt chest trauma and review its management.

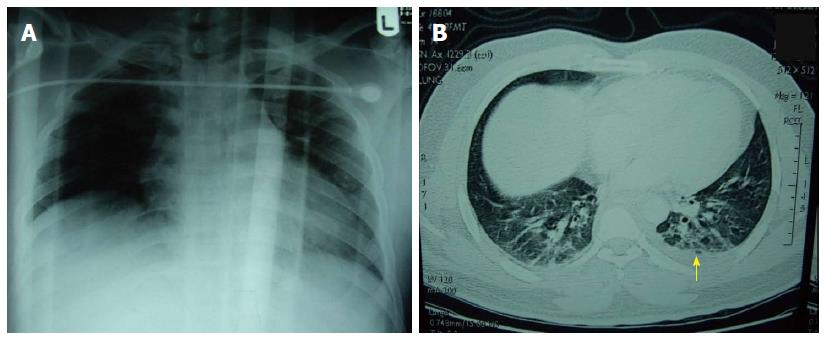

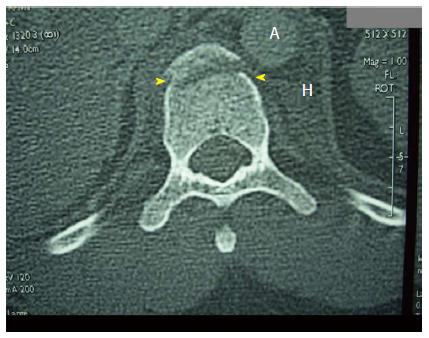

A 31-year-old man was brought to the Emergency Department, Al-Ain Hospital, after being involved in a road traffic collision in which he was ejected from a car during a roll over collision. He lost consciousness on the scene and was found outside the vehicle. He was not under the influence of alcohol or any recreational drug. Physical examination revealed a blood pressure of 148/92 mmHg, pulse of 96 bpm, respiratory rate of 24/min and Glasgow Coma Scale of 15/15. He was fully conscious, had mild neck tenderness, had a clear chest, and a soft abdomen. The patient had normal neurological function of the lower limbs. Chest X-ray showed mild white haziness on the left lung field and fracture of the right clavicle (Figure 1A). Computed tomography (CT) trauma showed the presence of mild pleural effusion on the left side (Figure 1B), fracture of the left lateral ramus of the sixth cervical vertebra, and fracture of the anterior rim of the tenth thoracic vertebra associated with haematoma around the descending aorta (Figure 2).

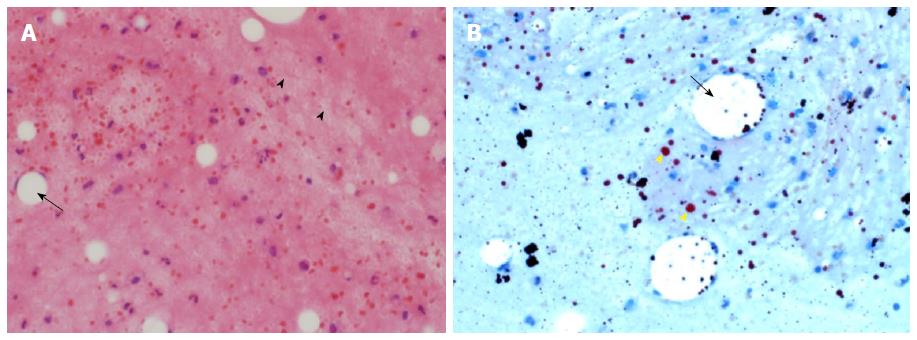

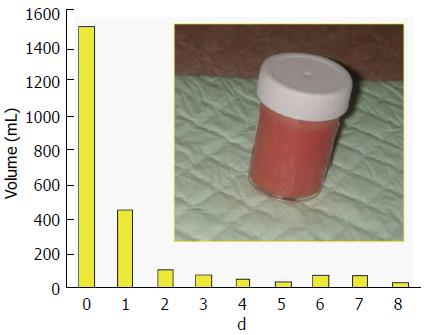

The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit for close observation. Chest X-ray on the second day showed homogenous whitish opacity on the left side suggestive of left pleural fluid (Figure 3). The trachea and mediastinum were shifted to the opposite side. A chest tube was inserted in the left pleural cavity. It directly drained 1500 mL of milky blood-stained fluid. Laboratory analysis of this fluid revealed that 80% of the cells were lymphocytes and 20% were neutrophils. Bacteriological culture of the fluid was negative. Blood cell count was normal (5.96 × 109/L). Histopathology of a cell block of the pleural fluid using Oil red O stain demonstrated that the fluid contained abundant fat globules associated with macrophages containing large fat vacuoles. In addition a few mixed inflammatory cells were present (Figure 4).

The patient was fed a fat free diet for 10 d. The fluid was milky for 6 d then became serous. The volume gradually declined in quantity (Figure 5). The chest tube was removed 9 d after its insertion after less than 50 mL of serous fluid had drained. CT scan of the chest on day 10 revealed complete resolution of the effusion (Figure 6). Blood albumin was normal on admission (35 g/L), dropped to 24 g/L on day 4 and was 39 g/L on discharge. The patient was discharged home in good condition on day 16.

Traumatic chylothorax may occur following cervical, thoracic or abdominal surgical procedures; as a result of malignancy; or as a result of penetrating or blunt trauma[7]. Chylothorax caused by blunt trauma is extremely rare. We have made a detailed search in Medline/PubMed and found only 31 cases of blunt traumatic chylothorax during the last 20 years (1995-2016), an average of 1.5 cases per year. The present case is the only one we have seen in our busy trauma centre in the last 15 years. Blunt traumatic chylothorax can be associated with fractures of the spine and/or posterior ribs[4,8,9]. Injury above the fifth or sixth thoracic vertebra generally results in left sided chylothorax, while injury below that level results in right-sided chylothorax[10]. Chest X-ray may reveal pleural effusion, and drainage of milky white pleural fluid may be indicative of chylothorax as occurred in our patient.

Injury of the thoracic duct can occur through one of three mechanisms: (1) hyperextension of the spine; (2) direct injury as a consequence of vertebral fracture; or (3) direct cut by the diaphragmatic crura[6,11,12]. We think that our patient possibly had an injury to one of the tributaries of the thoracic duct on the left side caused by the burst thoracic vertebra body because the patient responded rapidly to conservative management. Nevertheless, we cannot completely rule out a partial tear of the major thoracic duct leaking chyle with high concentration of lipids.

The diagnosis of chylothorax can be delayed especially in fasting patients when coupled with pleural drainage. We did not measure triglyceride or chylomicron levels in the pleural fluid which is however recommended to establish the diagnosis[2,10]. Although our diagnosis was clinically-based, we confirmed it by the histopathological findings of the cell block using Oil red O stain. Furthermore, lymphocytes are usually predominant in the chylothorax and culture is usually negative due to its bacteriostatic properties as occurred in our patient[7]. The differential diagnosis of a milky pleural fluid in a traumatic patient includes: (1) empyema; (2) tuberculosis; (3) chronic pleural effusion with high cholesterol level; and (4) traumatic chylothorax[2]. The first three diagnoses were unlikely in our patient for different reasons: (1) the initial chest X-ray was almost normal and returned to normal after chest tube drainage; (2) the patient did not develop fever or leukocytosis; (3) the patient recovered completely without specific antibiotic treatment; (4) the pleural fluid had 80% lymphocytes and its bacteriological culture was negative; (5) the patient responded well to the fat free diet; (6) CT scan showed a paravertebral haematoma on the left side of the tenth thoracic vertebra. This indicates that injury and bleeding were more on the left side of the vertebra and possibly including chyle leakage on the left side; and (7) histopathology confirmed that the pleural fluid was a fat rich fluid with minimum inflammatory cells.

Tension chylothorax may cause profound effects on cardiovascular haemodynamics[5,8]. Our patient had tension chylothorax. The left pleural cavity accommodated 1.5 L of chyle and both the trachea and mediastinum were displaced to the other side. We treated our patient conservatively. Initial management of chylothorax aims to decompress the pleural space and minimize chyle production by not feeding the patient via the enteral route. Total parenteral nutrition may be needed if a low fat diet does not reduce the volume of drained chyle[2]. Generally, a small chyle leak is managed conservatively. If there is a heavy loss of chyle it may lead to complications and surgery could be necessary.

It is agreed that conservative management is advised for two weeks, unless thoracotomy is indicated for another reason, in which case ligation of the thoracic duct can be carried out, or unless the patient’s nutritional status deteriorates rapidly due to significant chyle drainage[6,12]. Silen et al[4] reviewed the literature and found only 13 cases associated with thoracic vertebral fracture of whom 2 died, 6 patients required ligation of the thoracic duct, and 6 were treated conservatively.

Open mass ligation through a thoracotomy above the diaphragm is the most common surgical technique[5]. Other new approaches have been developed including ligation via thoracoscopy and thoracic duct embolization[2].

In conclusion, chylothorax caused by blunt trauma is extremely rare. It is usually suspected when a chest tube drains milky pleural fluid. Measuring pleural fluid triglyceride or chylomicron levels is recommended to establish the diagnosis. Conservative management is advised for at least two weeks before considering alternative interventional procedures.

The author thanks Ms. Geraldine Kershaw, Lecturer, Medical Communication and Study Skills, Department of Medical Education, College of Medicine and Health Sciences, UAE University for language and grammar corrections.

A 31-year-old man, who was involved in a road traffic collision, sustained fractures of the tenth thoracic vertebra, left pleural effusion, and haematoma around the descending aorta.

Left pleural effusion. A chest tube drained 1500 mL of milky blood-stained fluid.

Empyema, tuberculosis, chronic pleural effusion with high cholesterol level, or traumatic chylothorax.

Laboratory analysis of the pleural fluid revealed that 80% of the cells were lymphocytes and 20% were neutrophils. Bacteriological culture of the fluid was negative. Blood cell count was normal.

Chest X-ray showed homogenous whitish opacity on the left side suggestive of left pleural fluid. The trachea and mediastinum were shifted to the opposite side.

A cell block of the pleural fluid using Oil red O stain demonstrated that the fluid contained abundant fat globules associated with macrophages containing large fat vacuoles.

Chest tube drainage for 8 d. Feeding the patient fat free diet for 10 d.

Chylothorax caused by blunt trauma is extremely rare and can be associated with fractures of the spine. It is caused by injury of the thoracic duct through one of three mechanisms: (1) hyperextension of the spine; (2) direct injury as a consequence of vertebral fracture; and (3) direct cut by the diaphragmatic crura.

Chylothorax should be suspected when a chest tube drains milky pleural fluid following blunt chest trauma. Measuring pleural fluid triglyceride or chylomicron levels is recommended to establish the diagnosis.

Conservative management is advised for at least two weeks before considering alternative interventional procedures.

The paper discusses an extremely rare condition contributing to trauma literature. The case is interesting, well described, and the data are clearly related.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: United Arab Emirates

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Corbacioglu SK, Durandy YD S- Editor: Kong JX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Sendama W, Shipley M. Traumatic chylothorax: A case report and review. Respir Med Case Rep. 2015;14:47-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pillay TG, Singh B. A review of traumatic chylothorax. Injury. 2016;47:545-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | AlEassa EM, Al-Marashda MJ, Elsherif A, Eid HO, Abu-Zidan FM. Factors affecting mortality of hospitalized chest trauma patients in United Arab Emirates. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;8:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Silen ML, Weber TR. Management of thoracic duct injury associated with fracture-dislocation of the spine following blunt trauma. J Trauma. 1995;39:1185-1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chamberlain M, Ratnatunga C. Late presentation of tension chylothorax following blunt chest trauma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2000;18:357-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | McCormick J, Henderson SO. Blunt trauma-induced bilateral chylothorax. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:302-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Golden P. Chylothorax in blunt trauma: a case report. Am J Crit Care. 1999;8:189-192. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Glyn-Jones S, Flynn J. Traumatic tension chylothorax. Injury. 2000;31:549-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Townshend AP, Speake W, Brooks A. Chylothorax. Emerg Med J. 2007;24:e11. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Seitelman E, Arellano JJ, Takabe K, Barrett L, Faust G, Angus LD. Chylothorax after blunt trauma. J Thorac Dis. 2012;4:327-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kumar S, Mishra B, Krishna A, Gupta A, Sagar S, Singhal M, Misra MC. Nonoperative management of traumatic chylothorax. Indian J Surg. 2013;75:465-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ikonomidis JS, Boulanger BR, Brenneman FD. Chylothorax after blunt chest trauma: a report of 2 cases. Can J Surg. 1997;40:135-138. [PubMed] |