Published online Jul 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i7.671

Peer-review started: September 22, 2014

First decision: December 17, 2014

Revised: March 3, 2015

Accepted: April 1, 2015

Article in press: April 7, 2015

Published online: July 16, 2015

Processing time: 308 Days and 4.3 Hours

Gallbladder perforation (GBP) is a rare but serious complication of cholecystitis and needs to be managed promptly. Acalculus cholecystitis leading to GBP is frequently associated with enteric fever and found in critically ill patients, and a surgical approach is not always feasible in such patients. Use of percutaneous tube cholecystostomy (PTC) in such patients is a known entity but it is usually followed by interval cholecystectomy. Here we report a case of perforated gallbladder in a child managed conservatively and successfully with PTC as the definitive treatment wherein cholecystectomy was avoided. The functionality of the gallbladder was confirmed by a Tc99m-HIDA scan.

Core tip: Percutaneous cholecystostomy for selected patients with gallbladder perforation or distended gallbladder with symptoms is a good technique to tide over the acute crisis and may even avert the need for cholecystectomy.

- Citation: Dikshit V, Gupta R, Kothari P, Gupta A, Kamble R, Kesan K. Conservative management of type 2 gallbladder perforation in a child. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(7): 671-674

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i7/671.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i7.671

Gallbladder perforation (GBP) is rare in children and is seen as a complication of cholecystitis. Gallbladder stone disease is the most frequent cause of acute cholecystitis and acalculus cholecystitis is seen in only 5%-10% of cases[1]. The majority of the reported cases of GBP are associated with enteric fever. High level of suspicion, early diagnosis and prompt management are of paramount importance in dealing with this entity.

A 12-year-old male patient admitted on the medical side was referred to us with complaints of pain in the abdomen for 12 d. The pain was dull aching in nature, more in the right hypochondrium. He had a history of 7-8 episodes of vomiting, gastric in nature with mild fever and headache.

The child was febrile and had tachycardia. There was no icterus or features of liver failure. The abdomen was distended and there was guarding in the right hypochondrium without any rigidity. The liver was palpable 2 cm below the costal margin and the gallbladder was felt as a firm, globular and tender mass.

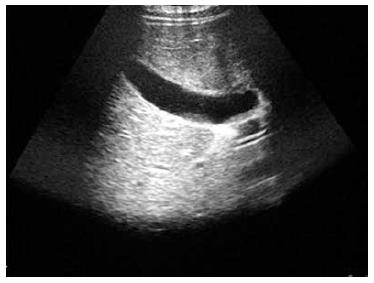

Complete haemogram, bilirubin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time and renal function tests, were within normal limits. Widal test and blood culture were negative. An erect X-ray of the abdomen was suggestive of gaseous distention of bowel loops. Ultrasonography (USG) on admission was suggestive of a hugely distended gallbladder with echogenic sludge within and mild hepatosplenomegaly. The patient was being treated conservatively and a follow-up USG was done 2 d later for persistence of pain. This time sonography revealed an over-distended (13 cm) gallbladder with perforation at the tip with a narrow tract and small volume of sealed-off collection with duodenal wall thickening and edema (Figure 1).

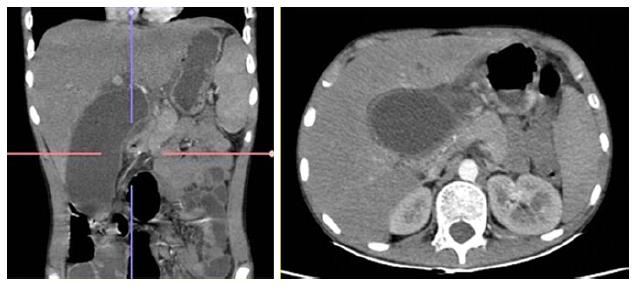

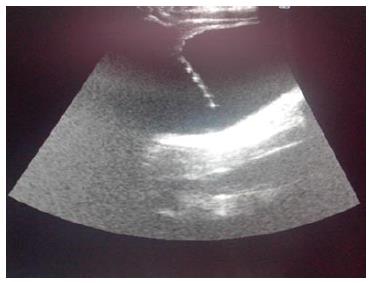

With these findings the patient was transferred to us and underwent a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen which confirmed the USG findings (8.5 mm sized rent seen in the gallbladder wall with mild peri-gallbladder collection 4.2 cm × 2.3 cm × 2.2 cm suspected of sealed-off gallbladder perforation. No free fluid was noted in the abdomen) (Figure 2). USG guided percutaneous cholecystostomy using an 8-Fr pigtail catheter was done and around 150 mL of bile was drained (Figure 3).

Bile culture showed Enterobacter species sensitive to piperacillin and amikacin. The patient received intravenous piperacillin at 250 mg/kg per day for 10 d and amikacin at 15 mg/kg per day for 5 d. Daily bile output through the cholecystostomy tube was around 120 to 140 mL. There was improvement in the patients’ general condition with resolution of fever and abdominal pain.

One week after the procedure bile culture showed no growth and liver function tests (LFTs) were normal. Tube cholecystogram showed free passage of contrast into the bowels (Figure 4), hence, intermittent clamping of the pigtail was started with monitoring for fever, pain and change in LFTs. Clamping trial after 4 d was successful and the pigtail was removed on post procedure day 13.

The patient was discharged symptom free and a Tc-99m Mebrofinin (HIDA) scan done 1 mo later showed morphologically normal liver with normal hepatic function and hepatobilliary drainage (Figure 5). At follow-up after 1 year of the episode, the patient remained to be asymptomatic.

GBP is a rare complication of acute cholecystitis (2%-11%)[1,2] and is more often seen in patients having critical illness like severe trauma, burns and cardiovascular surgeries. Compared with adult population GBP is even rarer in children and is mainly due to acalculus cholecystitis, trauma, enteric fever, gallbladder wall necrosis due to sepsis or sometimes it may occur spontaneously[3,4].

The most common part of the gallbladder to perforate is the fundus followed by the body, with the reason being attributed to poor blood supply[1]. The majority of the cases of cholecystitis followed by perforation are seen in gallbladder stone disease where the cystic duct often gets occluded, leading to retention of secretions and rise in the intraluminal pressure. Acalculus cholecystitis is seen in 5%-10% of patients with acute cholecystitis[1] and may lead to perforation as seen in our case.

GBP may be traumatic, iatrogenic or idiopathic (spontaneous) and was classified by Niemeier[5] into 3 types. Type 1 (acute) is associated with generalized biliary peritonitis; type 2 (subacute) consists of localized fluid collection at the site of perforation, pericholecystic abscess and localized peritonitis; and type 3 (chronic) has an internal or external fistula formation.

Most recent studies have cited highest rates of type 2 GBP and the same was the case in our patient.

Historically GBP has been associated with a high mortality rate which ranges from 11% to 26%[6] and great care must be taken to diagnose the condition as early as possible. Generally GBP mimics bowel perforation and many cases are diagnosed intra-operatively. Modalities useful for this condition are USG and CT scan, with the latter being more sensitive[1]. Abdominal X-ray may not always show free gas in the peritoneum. HIDA scan, retrograde cholangiography and peritoneal lavage may also be used[7].

Reported complications include bile peritonitis, intrahepatic abscess formation (possible mechanisms include direct extension, subcapsular extension and hematogenous dissemination via the portal vein), subhepatic abscess formation, pelvic abscess formation, pneumonia, pancreatitis and acute renal failure[8].

Once diagnosed GBP mandates early intervention, and cholecystectomy with peritoneal lavage is considered sufficient. Laproscopic approach may also be used[2]. In our patient USG and CT scan showed a sealed-off perforation without any free fluid in the peritoneum but a distended gallbladder which was persistent even on post prandial scans. Hence, a tube cholecystostomy was done under USG guidance by which the patient improved dramatically and a cholecystectomy was avoided. In many reports tube cholecystostomy is followed by interval cholecystectomy, but in our case we successfully avoided the procedure, thus preserving the gallbladder. Similar management in children has been reported by Mirza B[4] and Alghamdi[9]. The patient also underwent a Tc99m-HIDA scan to confirm the integrity and functionality of the biliary outflow tract, which did well at one-year follow-up.

It should also be mentioned that one must be very vigilant regarding the complications of GBP like persistent bile leak, persistent peritonitis, gallbladder necrosis, etc.[4] as they may warrant surgical exploration if not responding to percutaneous cholecystostomy.

In conclusion, we would like to highlight that GBP is a rare condition but demands a high level of suspicion, early diagnosis and prompt management. Using a percutaneous tube cholecystostomy in selected cases may help in avoiding cholecystectomy.

The patient was a 12-year-old boy who came with pain in the abdomen, fever and vomiting. He had abdominal distention and guarding in the right hypochondrium.

The initial suspicion was bowel perforation.

Gallbladder perforation, even though rare, was kept as a differential diagnosis due to guarding localized to right hypochondrium.

Complete hemogram, bilirubin, liver enzymes, prothrombin time and renal function tests, were within normal limits. Widal test and blood culture were negative.

An erect X-ray of the abdomen was unremarkable except gaseous distention of bowel loops. Ultrasonography revealed a perforated gallbladder which was confirmed by a computed tomography scan.

As the gallbladder remained persistently over distended and the patient continued to have fever, a tube cholecystostomy was performed which led to resolution of the symptoms. Tube cholecystogram showed free flow of bile into the bowel without any leak.

Similar technique of tiding over the acute phase of cholecystitis has been used before but is usually followed by interval cholecystectomy. In the case authors performed a HIDA scan at one month interval to confirm the functionality of the gallbladder and the billiary outflow system and found it satisfactory, thus cholecystectomy was successfully avoided.

Gallbladder perforation is a rare but serious complication of cholecystitis and needs to be managed promptly. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is a good technique to tide over such crisis and can even be used as the definitive treatment, thus avoiding cholecystectomy altogether.

This is an interesting case history.

P- Reviewer: Kumar A, Sartelli M, Soreide JA S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Alvi AR, Ajmal S, Saleem T. Acute free perforation of gall bladder encountered at initial presentation in a 51 years old man: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Derici H, Kara C, Bozdag AD, Nazli O, Tansug T, Akca E. Diagnosis and treatment of gallbladder perforation. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7832-7836. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Pandey A, Gangopadhyay AN, Kumar V. Gall bladder perforation as a complication of typhoid fever. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mirza B, Ijaz L, Saleem M, Iqbal S, Sharif M, Sheikh A. Management of biliary perforation in children. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 1990;7:147-150. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Wig JD, Chowdhary A, Talwar BL. Gall bladder perforations. Aust N Z J Surg. 1984;54:531-534. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Goel A, Ganguly PK. Gallbladder perforation: a case report and review of the literature. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:155-156. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Alghamdi HM. Acute Acalculous Cholecystitis Perforation in a Child Non-Surgical Management. Gastroent Res. 2012;5:174-176. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ergul E, Gozetlik EO. Perforation of gallbladder. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2008;109:210-214. [PubMed] |