Published online Apr 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i4.381

Peer-review started: June 8, 2014

First decision: June 27, 2014

Revised: January 20, 2015

Accepted: February 4, 2015

Article in press: February 9, 2015

Published online: April 16, 2015

Processing time: 312 Days and 2.3 Hours

This paper reports two cases of long QT syndrome (LQTS) which presented with seizures as their initial feature. Case 1, AB was seen in emergency department with post-partum seizure, discharged and re-presented following cardiac arrest associated with LQTS. Case 2, CD presented initially with tonic-clonic seizure and because of experience with AB, CD was assessed for LQTS which was subsequently confirmed. The legal medicine experience re Dobler v Halverson, which involved a young boy with LQTS, who suffered cardiac arrest without prior diagnosis of LQTS, has reinforced the requirement to seriously consider LQTS as an aetiological factor in first seizure presentations.

Core tip: Long QT syndrome (LQTS), with subsequent cerebral ischemia due to cardiac dysrhythmia, may cause seizures. It is imperative to consider LQTS in patients presenting with first seizure so as to avoid possible brain damage from prolonged cerebral hypoxemia. Failure to recognise LQTS may result in successful suit for negligence if not properly investigated and managed.

- Citation: Choong H, Hanna I, Beran R. Importance of cardiological evaluation for first seizures. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(4): 381-384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i4/381.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i4.381

Long QT syndrome (LQTS) represents channelopathies of cardiac potassium/sodium ion channels. Channelopathies may present with seizures and/or risk sudden death because ventricular dysrhythmia known as torsades de pointes (TdP).

AB was a 26-year-old Asian female, 6 wk post-partum with emergency lower cesarean section at 38 wk into her first pregnancy because of pre-eclampsia and fetal distress. Past medical and family histories were unremarkable and she was not on regular medication.

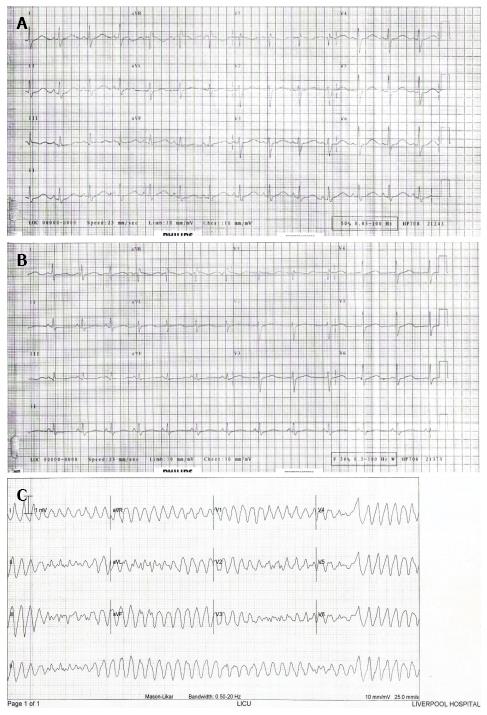

She had acute “dizziness” when rising from the sitting to standing position, and then collapsed to the floor and was witnessed to be cyanosed. Her husband performed cardiopulmonary resuscitation until the ambulance arrived. Her Glasgow Coma Scale improved with stable vital signs at that time. The paramedics witnessed an episode of generalised tonic-clonic seizure associated with tongue biting that lasted for a few minutes whilst en-route to Liverpool Hospital. In the Emergency Department, she was sedated and intubated because of post-ictal aggression. She was afebrile, blood pressure 127/78 mmHg and pulse rate 70 beats/min. Blood tests were unremarkable with normal computed tomography (CT) pulmonary angiogram, CT brain and CT cerebral venogram. Her electrocardiogram (ECG) showed corrected QT interval (QTc) of 526 ms (Figure 1A), which was above the normal limit for her gender (QTc < 460 ms). She was extubated 24 h later and was back to her normal state. Full neurological examination was unremarkable. No antiepileptic medication was prescribed as this was her first seizure. Electroencephalogram (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain were organised but she refused to stay in hospital for those investigations and was to be followed by the neurologist.

She was re-admitted the next day after being found unconscious. She was in ventricular fibrillation requiring cardioversion by the paramedics. Her ECG was similar to the previous recording, demonstrating abnormal QTc of 505 ms (Figure 1B) and hence prompting a diagnosis of LQTS. She had further symptomatic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia suggestive of TdP that required cardioversion (Figure 1C). She was subsequently started on beta-blocker therapy and had implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) for secondary prevention.

CD was a 50-year-old Caucasian male with no regular medication. His father died at 57 years old in his sleep.

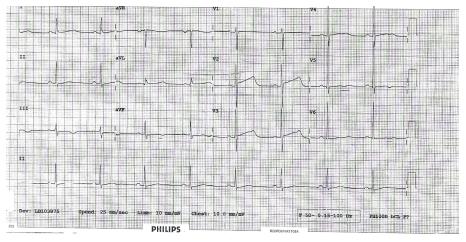

He presented to Liverpool Hospital with 2 min of witnessed generalised tonic-clonic seizure. This was associated with post-ictal drowsiness but no tongue biting or incontinence. Previously he had three episodes of unconsciousness. The first two were 30 years ago resulting in his being prescribed carbamazepine which he took for a few years but had not taken same for approximately 20 years. He was unable to provide adequate further history nor could he offer more detailed information regarding specific investigations related to those events. Full neurological and cardiological examinations, blood tests, EEG, MRI brain and echocardiography were all unremarkable. ECG showed QTc of 566 ms which was above the normal limit for his gender (QTc < 450 ms) (Figure 2) prompting a diagnosis of LQTS. Beta-blocker therapy was commenced. ICD was indicated due to his family history and possible ventricular dysrhythmias that could have accounted for his previous events of loss of consciousness thought possibly to be misdiagnosed as epileptic seizures.

Both patients in Cases 1 and 2 presented with generalised convulsive “seizures”. AB was initially discharged with conservative management and LQTS was diagnosed on representation. CD was diagnosed because of the experience with AB. This demonstrates that LQTS crosses age, gender and racial boundaries (AB being a young Asian female and CD a middle-aged Caucasian male) demanding a high index of suspicion and consideration of LQTS in all first seizures.

LQTS is a collection of genetically distinct arrhythmogenic disorders resulting in abnormal cardiac potassium and sodium ion channels causing delayed cardiac depolarization[1]. LQTS affects approximately 1 in 2000 people[2,3] and symptomatic cases may present with syncope, seizures or sudden death due to ventricular dysrhythmia known as TdP. These cases are often “erroneously” diagnosed as a primary seizure disorder, having unexplained syncope, or having ill defined “spells”[4,5] which could potentially lead to expensive legal-medicine consequences, such as the Dobler v Halverson case of 2006. This Australian, NSW Court of Appeal, case involved LQTS in a young boy diagnosed by a neurologist as a “faint” without further investigation. Halverson was then managed by his general practitioner (GP), Dr Dobler. Halverson experienced cardiac arrest with severe brain damage and the GP was found negligent for not performing an ECG nor organizing for cardiological assessment.

There is increasing support that seizures, in LQTS, are not solely due to acute cerebral hypoxic-ischemic event secondary to ventricular arrhythmias. It has been proposed that the aetiologies of LQTS and epilepsy may partly overlap via a possible link between the cardiac and neural ion channelopathies. It has been demonstrated that patients with LQTS type 2 are more commonly associated with epilepsy, hence supporting the possibility that mutation of KCNH2 gene responsible for LQTS type 2 may also predispose to seizure activity[5]. Similarly, various case reports and observational studies have suggested that mutation in the SCN5A gene, responsible for LQTS type 3, is also associated with epilepsy[6,7]. It follows that initial diagnosis of seizure disorder or epilepsy, with subsequent neurological investigations and antiepileptic treatment, may be inadequate if it does not also include cardiological evaluation. ECG, Holter monitoring and formal cardiological evaluation should become an integral part of a seizure/epilepsy assessment, to identify a subset of patients who also have concomitant LQTS. Failure to do so may predispose the patient to very serious or even fatal consequences and the treating clinician to subsequent personal and legal medicine ramifications.

Two cases presenting to hospital after witnessed generalised seizures.

Both cases had normal physical examination but had prolonged QTc on their electrocardiograms (ECGs), and evidence of torsades de pointes on the ECG for Case 1, prompting the diagnosis of long QT syndrome (LQTS).

Convulsive syncope, secondary to cardiogenic causes; primary or secondary generalised seizure disorder.

Both cases had normal routine blood tests, echocardiogram and electroencephalogram.

Both cases had normal computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging brain.

Beta-blocker medication and implantable cardioverter-defibrillator insertion were instigated after the diagnosis of LQTS in both cases.

There is a possible link between the cardiac and neural ion channelopathies, hence patients with LQTS may have concurrent primary epilepsy disorder causing seizures rather than solely from the consequences of the ventricular arrhythmias.

TdP refers to Tordes de Pointes which is an uncommon and distinctive form of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia characterized by a gradual change in the amplitude and twisting of the QRS complexes around the isoelectric line; Channelopathies are diseases caused by disturbed function of ion channel subunits or the proteins that regulate them; and KCNH2 and SCN5A are genetic abnormalities found to occur in both inherited epilepsies and LQTS.

Initial diagnosis of seizure disorder or epilepsy, with subsequent neurological investigations and antiepileptic treatment, may be inadequate if it does not also include cardiological evaluation.

The viewpoint of this paper is useful in clinical practice.

P- Reviewer: Tang FR, Tanaka N S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Ackerman MJ. The long QT syndrome: ion channel diseases of the heart. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:250-269. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Modi S, Krahn AD. Sudden cardiac arrest without overt heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:2994-3008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Anderson JH, Bos JM, Meyer FB, Cascino GD, Ackerman MJ. Concealed long QT syndrome and intractable partial epilepsy: a case report. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1128-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vincent GM, Timothy KW, Leppert M, Keating M. The spectrum of symptoms and QT intervals in carriers of the gene for the long-QT syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:846-852. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Johnson JN, Hofman N, Haglund CM, Cascino GD, Wilde AA, Ackerman MJ. Identification of a possible pathogenic link between congenital long QT syndrome and epilepsy. Neurology. 2009;72:224-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Parisi P, Oliva A, Coll Vidal M, Partemi S, Campuzano O, Iglesias A, Pisani D, Pascali VL, Paolino MC, Villa MP. Coexistence of epilepsy and Brugada syndrome in a family with SCN5A mutation. Epilepsy Res. 2013;105:415-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heron SE, Hernandez M, Edwards C, Edkins E, Jansen FE, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC. Neonatal seizures and long QT syndrome: a cardiocerebral channelopathy? Epilepsia. 2010;51:293-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |