Published online Dec 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i12.1005

Peer-review started: May 8, 2015

First decision: July 17, 2015

Revised: September 25, 2015

Accepted: October 20, 2015

Article in press: October 27, 2015

Published online: December 16, 2015

Processing time: 220 Days and 20 Hours

A 66-year-old, interferon-ineligible, treatment-naive man who was diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C due to hepatitis C virus genotype 1b began combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir. On day 14 of treatment, hepatic reserve and renal function deterioration was observed, while his transaminase levels were normal. Both daclatasvir and asunaprevir were discontinued on day 18 of treatment, because the patient complained of dark urine and a rash on his trunk and four limbs. After discontinuing antiviral therapy, the abnormal laboratory finding and clinical manifestations gradually improved, without recurrence. Our case fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of probable drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom (DRESS) syndrome. Despite the 18-d treatment, sustained virological response 12 was achieved. Based on the clinical course, we concluded that there was a clear cause-and-effect relationship between the treatment and adverse events. To our knowledge, this patient represents the first case of probable DRESS syndrome that includes concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function due to combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir, regardless of normalization of transaminase levels. Our case suggests that we should pay attention not only to the transaminase levels but also to allergic symptoms associated with organ involvement during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir.

Core tip: Oral combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for chronic hepatitis C demonstrates a relatively favorable safety profile. Although the incidence of hyperbilirubinemia, hypoalbuminemia, and a decreased prothrombin activity have been reported, as well as renal damage, concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function without transaminase elevations have not been reported. We observed probable drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom syndrome, including concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function due to the combination therapy, regardless of normalized transaminase levels. Thus, our case highlights the importance of paying attention not only to transaminase levels but also to the allergic symptoms associated with organ involvement during combination therapy.

- Citation: Suga T, Sato K, Yamazaki Y, Ohyama T, Horiguchi N, Kakizaki S, Kusano M, Yamada M. Probable case of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom syndrome due to combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(12): 1005-1010

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i12/1005.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i12.1005

Combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir has been approved as oral antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C due to hepatitis C virus (HCV) genotype 1b. This new type of therapy resulted in a sustained virological response (SVR) rate of over 80% after 24 wk of therapy for chronic hepatitis C patients with genotype 1b[1,2]. In Japan, combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir has been recommended for interferon-ineligible patients based on the Japan Society of Hepatology guidelines for managing HCV infection[3].

One of the most frequent adverse events during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir is elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. In an open-label trial of oral antiviral therapy conducted in Japan[1,4,5], ALT elevations occurred in 17.6% of the patients treated with a combination of daclatasvir and asunaprevir. The incidence of hyperbilirubinemia, hypoalbuminemia or prothrombin activity decrease, which reflect deteriorated hepatic reserve[6-8], were 3.9%, 1.2% or 0.8%, respectively[1,4,5]. The incidence of renal damage was 0.4%[1,4,5]. However, concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function without transaminase elevations has not been reported. Here, we report a case of chronic hepatitis C with concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function that fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of probable drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom (DRESS) syndrome[9] due to combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir. We got written informed consent from the patient in advance.

A 66-year-old man, diagnosed with chronic hepatitis C (genotype 1b) at the age of 50, was started on a scheduled 24-wk course of daclatasvir and asunaprevir for elevated transaminase levels. The patient suffered from a duodenal ulcer, bronchial asthma, hypertension and cerebral hemorrhage. He had undergone antihypertensive therapy with nifedipine and olmesartan for 5 years. These drugs were maintained throughout the antiviral treatment. No relevant family history was noted. The patient did not have a past history or predisposing factors for liver disease, except for chronic hepatitis C. He had no history of drug allergies, although he did have bronchial asthma. Combination therapy with daclatasvir (60 mg once daily) and asunaprevir (100 mg twice daily) was selected because the patient was both interferon-ineligible and interferon-naïve due to his past history of hypertension and cerebral hemorrhage. A V170I mutation in the NS3 lesion was detected by direct sequencing prior to the therapy. Before beginning therapy, the following measurements were noted: serum ALT, 57 IU/L; total bilirubin, 0.5 mg/dL; albumin, 4.1 g/dL; creatinine, 0.7 mg/dL; prothrombin activity, 102%; total white cell count, 5000/μL (eosinophils 150/μL); platelet count, 11.1 × 104/μL; C-reactive protein, < 0.1 mg/dL, and HCV RNA, 5.9 Log IU/mL.

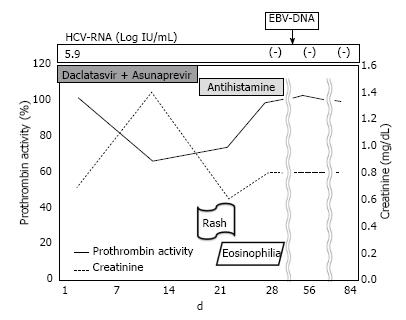

On day 14 of treatment, the patient’s laboratory findings showed concomitant deterioration of hepatic reserve and renal function, without any subjective symptoms. Although the ALT level had decreased to 22 IU/mL, serum total bilirubin had worsened to 1.9 mg/dL, albumin to 3.3 g/dL, creatinine to 1.4 mg/dL, prothrombin activity to 66.4%, total white cell count to 12130/μL (eosinophils 121/μL), platelet count to 7.9 × 104/μL and C-reactive protein to 3.5 mg/dL (Table 1). Abdominal ultrasonography revealed splenomegaly, which was not present before the therapy. There was no evidence of biliary obstruction. Daclatasvir and asunaprevir were continued. The patient complained of headache, dark urine and a partly fused erythematous rash on his trunk and four limbs on day 18 of treatment. In view of the skin lesions, a dermatologist diagnosed the skin rash as a drug eruption or untypical urticarial lesion (Figure 1), although the patient’s vital signs were normal: temperature 36.5 °C, blood pressure 121/58 mmHg and heart rate 72/min. Both daclatasvir and asunaprevir were discontinued based on the dermatologist’s advice and the patient’s request, and an antihistamine was administered for 2 wk. When observed on day 21 of the initiation of treatment, the clinical manifestations had disappeared, and the laboratory findings had returned to normal ranges, except for the serum albumin (3.4 g/dL), prothrombin activity (74.5%) and eosinophilia (2673/μL) levels. These measurements also returned to normal ranges, until day 35 of the initiation of treatment. On day 42 of the initiation of treatment, molecular biological analysis detected Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA but not human herpesvirus (HHV)-6 and HHV-7 DNA in the serum. Although daclatasvir and asunaprevir were discontinued on day 18 of treatment, SVR 12 was achieved (serum HCV RNA was negative after 12 wk of treatment). The clinical course of our case and the time course for the critical laboratory values are shown in Figure 2 and Table 2, respectively.

| On day 14 of antiviral therapy | Virological analysis before antiviral therapy | ||||

| Hematology | Virus markers | Virus marker | |||

| WBC (μL) | 12130 | IgM-HAV Ab | (-) | HCV RNA (Log IU/mL) | 5.9 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 82 | HBs Ag | (-) | ||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 10 | IgM-HBc Ab | (-) | Drug resistant variants | |

| Monocytes (%) | 6 | HBV DNA | (-) | NS3/V36A | (-) |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1 | IgA-HEV Ab | (-) | NS3/T54A | (-) |

| RBC (μL) | 4000000 | IgM-HSV Ab | (-) | NS3/T54S | (-) |

| Hb (g/dL) | 13.2 | IgG-HSV Ab | (+) | NS3/Q80L | (-) |

| Plt (μL) | 79000 | IgM-HHV6 Ab | (-) | NS3/Q80R | (-) |

| IgG-HHV6 Ab | (+) | NS3/R155K | (-) | ||

| Blood chemistry | IgM-CMV Ab | (-) | NS3/R155Q | (-) | |

| TP (g/dL) | 7.4 | IgG-CMV Ab | (+) | NS3/R155T | (-) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 | IgM-EBV VCA Ab | (-) | NS3/A156S | (-) |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 1.9 | IgG-EBV VCA Ab | (+) | NS3/A156T | (-) |

| D-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.7 | EBNA Ab | (+) | NS3/A156V | (-) |

| AST (IU/L) | 15 | NS3/D168A | (-) | ||

| ALT (IU/L) | 22 | Endocrine | NS3/D168E | (±)2 | |

| ALP (IU/L) | 284 | TSH (μIU/mL) | 1.7 | NS3/D168H | (-) |

| γ-GTP (IU/L) | 33 | fT3 (pg/mL) | 2.81 | NS3/D168T | (-) |

| LDH (IU/L) | 147 | fT4 (ng/dL) | 1.1 | NS3/D168V | (-) |

| ChE (IU/L) | 257 | NS3/V170I | (+)2 | ||

| T. Chol (mg/dL) | 126 | Serology | NS5A/L31F | (-) | |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 28 | IgA (mg/dL) | 130 | NS5A/L31M | (-) |

| Cr (mg/dL) | 1.4 | IgE (mg/dL) | 526 | NS5A/L31V | (-) |

| UA (mg/dL) | 5.4 | IgG (mg/dL) | 2225 | NS5A/Y93H | (±)2 |

| CPK (IU/L) | 60 | IgM (mg/dL) | 104 | ||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 3.5 | RF | (-) | ||

| BNP (pg/mL) | 20.1 | ANA | × 40 (+) | ||

| Fe (μg/dL) | 123 | AMA | (-) | ||

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 115 | ASMA | (-) | ||

| Hyaluronic acid1 (ng/mL) | 179 | ||||

| Collagen-41 (ng/mL) | 298 | Tumor markers | |||

| PIVKA-2 (mAU/mL) | 19 | ||||

| Blood coagulation | AFP (ng/mL) | 6.6 | |||

| PT (%) | 66.4 | ||||

| PT-INR | 1.22 | DLST | |||

| Daclatasvir | (-) | ||||

| Asunaprevir | (-) | ||||

| Before antiviral therapy | Day 14 of treatment | Day 21 of the initiation of treatment (day 3 after discontinuation of the treatment) | Day 35 of the initiation of treatment (day 17 after discontinuation of the treatment) | |

| Hematology | ||||

| WBC (μL) | 5000 | 12130 | 7800 | 5950 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 82 | 35 | 47 | |

| Lymphocytes (%) | 10 | 26 | 43 | |

| Monocytes (%) | 6 | 6 | 7 | |

| Eosinophils (%) | 1 | 32 | 3 | |

| Plt (μL) | 111000 | 79000 | 130000 | 115000 |

| Blood chemistry | ||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 4.1 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4.2 |

| T-Bil (mg/dL) | 0.5 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| D-Bil (mg/dL) | 0 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| AST (IU/L) | 57 | 15 | 17 | 28 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 57 | 22 | 18 | 23 |

| ChE (IU/L) | 311 | 257 | 204 | 276 |

| T. Chol (mg/dL) | 170 | 126 | 140 | 179 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 13 | 28 | 6 | 16 |

| Cre (mg/dL) | 0.7 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.1 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 0 |

| Blood coagulation | ||||

| PT (%) | 102 | 66.4 | 74.5 | 95.5 |

| PT-INR | 1.01 | 1.22 | 1.16 | 1.04 |

Here, we described a case of deteriorated hepatic reserve and renal function during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir, regardless of normalized transaminase levels at the development of the symptoms. The decreased cholinesterase and total cholesterol values were also consistent with deteriorated hepatic reserve[10,11]. Drug-induced liver injury generally results in abnormal biochemical liver tests, including transaminase or alkaline phosphatase[12]. In our case, the normal values of transaminase and alkaline phosphatase did not fulfill the diagnostic criteria of drug-induced liver injury. However, the clinical course was similar to that of drug-induced liver injury, key elements of which are drug exposure preceding the onset of liver injury, the exclusion of underlying liver disease, including obstructive jaundice, and improvement after discontinuing the drug[12,13]. Because there have been case reports showing severe liver injury or hepatic decompensation during the therapy of direct-acting antivirals, including telaprevir[14] or simeprevir[15], daclatasvir or asunaprevir may also induce liver injury, with deteriorated hepatic reserve.

The present case also demonstrated renal damage and rash on the trunk and four limbs, which were accompanied by inflammatory reaction and eosinophilia after starting therapy, thereby indicating the possibility of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). The patient’s atopic background, including bronchial asthma, was also a risk factor of drug allergy[16]. In fact, a case associated with DIHS during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir has been reported[17]. The renal damage was not due to dehydration or urinary tract infection; thus, organ involvement associated with a series of symptoms was considered. Rapidly enlarging rash and deteriorating hepatic reserve, as well as eosinophilia and EBV reactivation[18], are the typical hallmark features of DIHS, which might be responsible for the pathophysiology in our case. However, the lack of fever, lymphadenopathy, and HHV-6 reactivation were inconsistent with DIHS. Thus, our case did not fulfil the diagnostic criteria of even atypical DIHS, according to the diagnostic criteria of DIHS[19]. During this therapy, our case was fundamentally different from the case associated with DIHS[17] because our patient did not have lymphadenopathy, fever, ALT elevation but had other organ involvement, such as renal damage.

However, as a severe, adverse, drug-induced reaction, DRESS syndrome is similar to DIHS. DRESS syndrome is characterized by a delayed onset, usually 2-6 wk after the initiation of drug therapy, as well as the possible persistence or aggravation of symptoms, despite the discontinuation of the causative drug; severe skin eruption, fever, hematologic abnormalities (eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytes) and internal organ involvement are also associated with DRESS syndrome. In this case, the patient showed eosinophilia (more than 1500/μL, with a DRESS score of 2), and skin rash (more than 50%), which were indicative of DRESS; in addition, there was liver and kidney involvement and the absence of other potential causes (each with a DRESS score of 1). There were no enlarged lymph nodes or atypical lymphocytes, and the skin biopsy was not performed, thus each received a DRESS score of 0, and high fever was not observed (less than 38.5 °C, with a DRESS score of -1). However, the resolution within 15 d is uncertain. If we estimate this evaluation item at a score of -1, the score of our case was at least 5; therefore, our case was considered to be a probable case, according to the RegiSCAR scoring system[9]. The possible mechanisms of the DRESS syndrome are detoxification defects, which can lead to reactive metabolite formation and subsequent immunological reactions, slow acetylation, and reactivation of human herpesvirus, including EBV, HHV-6 and -7[9].

Both daclatasvir and asunaprevir are metabolized by CYP3A, and asunaprevir is a substrate of OATP1B1[20]. CYP3A activity and OATP1B1 activity are known to be decreased in advanced liver disease and cirrhosis[21,22]. Prior to antiviral therapy, the platelet count, hyaluronic acid and type IV collagen levels suggested hepatic fibrosis in our case[23,24]. Moreover, nifedipine (one of the concomitant drugs) is metabolized by CYP3A and, thus, may compete against daclatasvir and asunaprevir as the substrate. Another concomitant drug, olmesartan, is a substrate of OATP1B1 and, thus, may compete against daclatasvir and asunaprevir as the substrate. Drug interactions may also increase the blood concentration of daclatasvir and asunaprevir. Therefore, higher blood levels of daclatasvir or asunaprevir (based on low hepatic metabolic ability) might cause unexpected adverse events. Indeed, in our case, the achievement of SVR12 supported this hypothesis. As a combination therapy, daclatasvir and asunaprevir are also approved in compensated cirrhosis patients (Child-Pugh A), and careful observation is particularly needed for these patients.

Based on the decreased prothrombin activity and platelet count, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) was a differential diagnosis in our case. Unfortunately, we did not measure the fibrin degradation products, D-dimer, and fibrinogen levels at the onset of the deteriorated laboratory data. According to the ISTH Diagnostic Scoring System for DIC, the score in our case was considered to be 5, at most. Thus, we think that overt DIC was a possible but not the probable diagnosis.

In summary, we experienced an unusual case of probable DRESS syndrome due to combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir. We should pay attention not only to the transaminase levels but also to the allergic symptoms associated with organ involvement during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir.

Dark urine and a rash on his trunk and four limbs.

Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptom (DRESS) syndrome due to combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir.

The ISTH Diagnostic Scoring System for disseminated intravascular coagulopathy and diagnostic criteria of drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome.

Blood drawing and urine collection showed that hepatic reserve and renal function deterioration, eosinophilia and dark urine, respectively.

Inspection of skin and photographic evidence of a skin rash.

Both daclatasvir and asunaprevir were discontinued and an antihistamine was administered for 2 wk.

The reference #1 for the understanding of combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir, and #9 for the understanding of The DRESS syndrome.

DRESS syndrome: DRESS syndrome is characterized by a delayed onset, usually 2-6 wk after the initiation of drug therapy, as well as the possible persistence or aggravation of symptoms, despite the discontinuation of the causative drug; severe skin eruption, fever, hematologic abnormalities (eosinophilia or atypical lymphocytes) and internal organ involvement are also associated with DRESS syndrome.

We should pay attention not only to the transaminase levels but also to the allergic symptoms associated with organ involvement during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir.

It is a very interesting and well explained case worth sharing with the scientific community.

P- Reviewer: Palmero D, Reviriego C S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Kumada H, Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ido A, Yamamoto K, Takaguchi K. Daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for chronic HCV genotype 1b infection. Hepatology. 2014;59:2083-2091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 468] [Cited by in RCA: 488] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Manns M, Pol S, Jacobson IM, Marcellin P, Gordon SC, Peng CY, Chang TT, Everson GT, Heo J, Gerken G. All-oral daclatasvir plus asunaprevir for hepatitis C virus genotype 1b: a multinational, phase 3, multicohort study. Lancet. 2014;384:1597-1605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 289] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Drafting Committee for Hepatitis Management Guidelines, the Japan Society of Hepatology. JSH Guidelines for the Management of Hepatitis C Virus Infection: A 2014 Update for Genotype 1. Hepatol Res. 2014;44 Suppl S1:59-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suzuki Y, Ikeda K, Suzuki F, Toyota J, Karino Y, Chayama K, Kawakami Y, Ishikawa H, Watanabe H, Hu W. Dual oral therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir for patients with HCV genotype 1b infection and limited treatment options. J Hepatol. 2013;58:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chayama K, Takahashi S, Toyota J, Karino Y, Ikeda K, Ishikawa H, Watanabe H, McPhee F, Hughes E, Kumada H. Dual therapy with the nonstructural protein 5A inhibitor, daclatasvir, and the nonstructural protein 3 protease inhibitor, asunaprevir, in hepatitis C virus genotype 1b-infected null responders. Hepatology. 2012;55:742-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 284] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sherlock SP. Biochemical investigations in liver disease; some correlations with hepatic histology. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1946;58:523-544. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Rothschild MA, Oratz M, Zimmon D, Schreiber SS, Weiner I, Van Caneghem A. Albumin synthesis in cirrhotic subjects with ascites studied with carbonate-14C. J Clin Invest. 1969;48:344-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Robert A, Chazouillères O. Prothrombin time in liver failure: time, ratio, activity percentage, or international normalized ratio? Hepatology. 1996;24:1392-1394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cacoub P, Musette P, Descamps V, Meyer O, Speirs C, Finzi L, Roujeau JC. The DRESS syndrome: a literature review. Am J Med. 2011;124:588-597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 10. | Burnett W. An assessment of the value of serum cholinesterase as a liver function test and in the diagnosis of jaundice. Gut. 1960;1:294-302. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Habib A, Mihas AA, Abou-Assi SG, Williams LM, Gavis E, Pandak WM, Heuman DM. High-density lipoprotein cholesterol as an indicator of liver function and prognosis in noncholestatic cirrhotics. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:286-291. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Fontana RJ, Seeff LB, Andrade RJ, Björnsson E, Day CP, Serrano J, Hoofnagle JH. Standardization of nomenclature and causality assessment in drug-induced liver injury: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2010;52:730-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Navarro VJ, Senior JR. Drug-related hepatotoxicity. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:731-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 690] [Cited by in RCA: 642] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gordon SC, Muir AJ, Lim JK, Pearlman B, Argo CK, Ramani A, Maliakkal B, Alam I, Stewart TG, Vainorius M. Safety profile of boceprevir and telaprevir in chronic hepatitis C: real world experience from HCV-TARGET. J Hepatol. 2015;62:286-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stine JG, Intagliata N, Shah NL, Argo CK, Caldwell SH, Lewis JH, Northup PG. Hepatic decompensation likely attributable to simeprevir in patients with advanced cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:1031-1035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Idsoe O, Guthe T, Willcox RR, de Weck AL. Nature and extent of penicillin side-reactions, with particular reference to fatalities from anaphylactic shock. Bull World Health Organ. 1968;38:159-188. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Fujii Y, Uchida Y, Mochida S. Drug-induced immunoallergic hepatitis during combination therapy with daclatasvir and asunaprevir. Hepatology. 2015;61:400-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Seishima M, Yamanaka S, Fujisawa T, Tohyama M, Hashimoto K. Reactivation of human herpesvirus (HHV) family members other than HHV-6 in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shiohara T, Iijima M, Ikezawa Z, Hashimoto K. The diagnosis of a DRESS syndrome has been sufficiently established on the basis of typical clinical features and viral reactivations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:1083-1084. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kiser JJ, Burton JR, Everson GT. Drug-drug interactions during antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:596-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chalasani N, Gorski JC, Patel NH, Hall SD, Galinsky RE. Hepatic and intestinal cytochrome P450 3A activity in cirrhosis: effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2001;34:1103-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kojima H, Nies AT, König J, Hagmann W, Spring H, Uemura M, Fukui H, Keppler D. Changes in the expression and localization of hepatocellular transporters and radixin in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2003;39:693-702. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Fontana RJ, Goodman ZD, Dienstag JL, Bonkovsky HL, Naishadham D, Sterling RK, Su GL, Ghosh M, Wright EC. Relationship of serum fibrosis markers with liver fibrosis stage and collagen content in patients with advanced chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2008;47:789-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |