Published online Jan 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i1.77

Peer-review started: July 1, 2014

First decision: August 14, 2014

Revised: October 14, 2014

Accepted: October 23, 2014

Article in press: December 23, 2014

Published online: January 16, 2015

Processing time: 197 Days and 17.9 Hours

Xanthogranulomas (XG) are benign proliferative disorder of histiocytes, a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Whose etiology is unknown. The nature of these lesions is controversial and could be either reactive or neoplastic; the presence of monoclonal cells does, however, favor the second hypothesis. Xanthogranuloma is frequently found in young adults and children (under 20 years old), mainly in the skin. In about 5%-10% of all Juvenile XG (JXG) cases xanthogranuloma are extracutaneous. Within this group, the site most frequently involved is the eye. Other involved organs are heart, liver, adrenals, oropharynx, lung, spleen, central nervous system and subcutaneous tissue, although involvement of the spine is uncommon. Isolated lesions involving the sacral region are extremely rare. To date, this is the first reported case of a giant JXG arising from S1 with extension into the pelvic region in an adult spine.

Core tip: Xanthogranulomas (XG) are benign lesions derived by histiocytes, also called histiocytosis with non-Langerhans cell. Isolated xanthogranuloma involving the sacral region are unique. We report the unique giant Juvenile XG arising from S1 with extension into the pelvic region in an adult spine. Complete surgical removal is the goal of the treatment and usually curative even if there is not a study in the literature with a long follow up able to confirm this. If total resection is not possible, the patients must be followed by strictly clinical examination or should undergo adjuvant radiotherapy.

- Citation: Marotta N, Landi A, Mancarella C, Rocco P, Pietrantonio A, Galati G, Bolognese A, Delfini R. Giant xanthogranuloma of the pelvis with S1 origin: Complete removal with only posterior approach, technical note. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(1): 77-80

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i1/77.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i1.77

Xanthogranulomas (XG) are benign proliferative disorder of histiocytes, a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis[1]. Whose etiology is unknown. The nature of these lesions is controversial and could be either reactive or neoplastic; the presence of monoclonal cells does, however, favor the second hypothesis[2]. Xanthogranuloma is frequently found in the skin of young population, especially under 20 years old. In about 5%-10% of all Juvenile XG (JXG) cases xanthogranuloma is extracutaneous. Within this group, the eye appears to be the site most frequently involved. Other involved organs include the oropharynx, heart, liver, lung, spleen, adrenals, muscles , central nervous system and the subcutaneous tissues, although involvement of the spine is uncommon[1]. Isolated xanthogranuloma of the sacral region are extremely rare[1,3]. To date, this is the first case of a giant JXG arising from S1 with extension into the pelvic region in an adult spine.

A 44-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a 9 mo history of pollakiuria, stypsis, and sciatica along the S2 left dermatome, the symptoms appeared slowly worsening. The patient underwent lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with gadolinium that demonstrated the presence of a presacral, giant, well-circumscribed round formation. The lesion compressed the left S4, S3 and S2 roots and dislocated the urinary bladder, rectum, and iliac artery, and it extended ventrally from the left articular mass of S1 to the pelvic region. The lesion was hypointense on T1 weighted images and isointense on T2 ones with dishomogeneous contrast enhancement after gadolinium diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA) (Figure 1). The computed tomography (CT) bone scanning showed the erosion of S3-S4 foramen and bone involvement of left sacral wing. On physical examination, the patient had a positive right Lasegue sign. Rectal inspection revealed the presence of a posterior hard-elastic lesion.

The patient underwent CT-guided biopsy at the division of general surgery of the Policlinico Umberto I. A juvenile xantogranuloma was diagnosed at the histological examination. The patient was then referred to our attention and underwent surgery performing a posterior approach: the patient was placed in prone position; Intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring has been utilized. A standard electromyography monitoring of L4, L5 and S1 was conducted bilaterally. Moreover the insertion of electrodes in the urethra and anal sphincter during the surgical procedure helps to discriminate between nerve root and tumor. A U shaped skin incision was performed, followed by a complete exposure of the spinal column and partially of the sacro-iliac region with prevalent lateral extension on the left side. A complete laminectomy and partial left sacrectomy (25% of left sacrum removal) was performed. Because of the benign nature of the lesion and the space formed by tumor growth, we performed a less invasive procedure with intralesional posterior tumor removal, obtaining enough space without total sacrectomy that could be destabilizing for spine. We used the posterior approach to easily reach the lesion right after the opening of the subcutaneous layer and because it was easier to reach the origin point of the lesion and to control the S2, S3 and S4 root. Intraoperatively, the lesion appeared xanthochromic, friable, moderately bloody and presented a discontinuous capsule. The consistency was really flabby so that the cranial part of the tumor was easily mobilization and the removal was safe for structures as like as rectum and sacral plexus. The lesion was very adherent to the surrounding tissues. The lesion was macroscopically total removed. Immediately after surgery, the patient had relief of pain and had a progressive resolution of sphincter disturbances, with complete recovery after 15 d from surgery. A complete removal of the tumor was shown in the postoperative spine MRI (Figure 2). The patient was discharged on the tenth postoperative day. Clinical follow-up at 1 year showed the stability of symptoms. Radiological follow up using MRI (3T, T1, T2, STIR, T1 sequences with contrast) at 3, 6 and 12 mo showed no signs of recurrent disease.

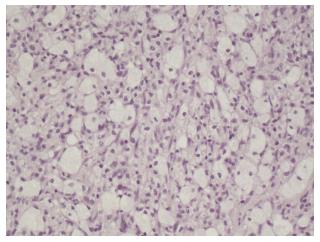

Gross examination showed a 13 cm × 10 cm × 13 cm round lesion, discontinuously encapsulated and adherent to surrounding tissues. The cut surface was homogeneous, yellow and of gelatinous consistency. Microscopic examination revealed the presence of typical touton giant cells. In general, a finding of such cells is sufficient for a diagnosis of xanthogranuloma. Immunohistochemical studies, in one of Dehner’s series, showed an immunopositive response for CD68, factor XIIIa and Vimentin of the tumor cells, and are not reactive for S100 and CD1a (Figure 3)[4].

Proliferative disorders of histiocytes were described in 1905 by Adamson[5]. Those diseases comprehend a group of pathologies in which the main hstological patterns are dendritic cells and macrophages. The xanthogranuloma has called a non-Langerhans cell histiocytosis as soon as other entities as: Rosai-Dorfman disease (if associated with lymphadenopathy), benign cephalic histiocytosis, the papular xanthoma, and hemophagocytic histiocytosis. Xanthogranuloma is usually benign and is also known as juvenile because it occurs predominantly in young people under the age of twenty years[1]. Etiology of JXG is unknown, but probably is the result of alteration in macrophagic response to an aspecific injury, resulting in a granuloma.

On the other hand, the recent discovery of the monoclonal nature of the cell population of these lesions, has suggested a possible neoplastic origin[2]. The skin of neck and head are the most frequent location of the JXG 67%[3]. It can be multiple or solitary with red-to-yellowish nodules and papules. The involvement of extracutaneous tisuues occurs in about 5%-10% and mainly involves eyes (uvea). Involvement has been reported in other organs including the lung, heart, liver, oropharynx, central nervous system, spleen, adrenals, muscles and subcutaneous tissues, although spinal involvement is extremely rare[3]. The lesions are self-limiting regressing over several years and predominantly occur in childhood. In these cases, conservative treatment and clinical observation is therefore indicated. Adults do not usually experience spontaneous resolution[3] and injuries may present invasive characteristics, meaning that surgical procedures become the treatment of choice. The gold standard radiological examination is MRI, useful for defining the localization and relation to the other structures. Today a standard treatment for extracutaneous JXG is not defined. However, literature indicates that total removal of the tumor is the treatment of choice and it is important the excision of the origin of the tumor. According to some authors, en-bloc excision of the lesion to healthy margins could be a curative treatment option. If total resection is not possible, the patients should be followed under medical observation or be submitted to adjuvant radiotherapy[3]: if the symptoms recur, the patients should be re-operated[1]. On the other hand, radiation treatment, besides not being free from complications, poses the lesion at risk of malignant transformation. To date, this is the first case of giant JXG arising S1 with extension into the pelvic region in an adult spine. All spinal surgeons know and understand the risk of vascular injury because iliac arteries, aorta, and other vascular structures are strictly related to the anterior lumbar spine. We used the posterior approach to reduce the risk of vascular injury, to easily reach the lesion right after the opening of the subcutaneous layer and the origin point of the lesion and to control the S2, S3 and S4 root. Although the depth of the cable and the relationships with the adjacent vascular structures made it particularly difficult to remove the lesion, total removal was achieved by a posterior approach. The placing of neurophysiological electrodes monitor during the surgical procedure in the urethra sphincter and anal sphincter allows surgeons to distinguish between nerve roots and tumor, and to prevent urinary dysfunctions.

The follow-up at one year showed an improvement in reported preoperatively symptoms and confirmed radical removal, without any signs of disease recurrence.

A standard treatment for extracutaneous JXG is not still accepted. However, complete surgical removal is the goal of treatment although the size and the aggressive behavior of the tumor may condition the procedure. Complete surgical removal is usually curative even if there is not a study in the literature with a long follow up able to confirm this. If total resection is not possible, the patients have to be followed under close medical observation or should undergo adjuvant radiotherapy. Important is the use of neurophysiological monitoring especially of the pelvic region to prevent any neurological dysfunction.

Pollakiuria, stypsis, and sciatica along the S2 left dermatome.

On physical examination, the patient had a positive right Lasegue sign. Rectal inspection revealed a posterior hard-elastic lesion.

Lumbosacral magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium demonstrated the presence of a presacral, giant, well-circumscribed round formation. A computed tomography bone scanning showed erosion of the left sacral wing at S3-S4 foramen.

Microscopic examination revealed the presence of typical touton giant cells. In general, a finding of such cells is sufficient for a diagnosis of xanthogranuloma.

Surgical treatment.

The recent discovery of the monoclonal nature of the cell population of these lesions, has suggested a possible neoplastic origin. The lesions are self-limiting and predominantly occur in infancy and childhood, and typically regress over several years. In these cases, conservative treatment and clinical observation is therefore indicated. Adults do not usually experience spontaneous resolution and injuries may present invasive characteristics, meaning that surgical procedures become the treatment of choice.

Xanthogranuloma, a proliferative histiocytic disorders.

Complete surgical removal is the gold standard for the treatment of this pathology.

The paper describes a rare (probably unique) case of symptomatic giant xanthogranulomas of the pelvis in a 40 years old male. Authors explain clearly why they decided to manage surgically the lesion. Excision was successfully performed trough a posterior route to avoid damages to the surrounding neurovascular structures. Symptoms relief was immediate and preserved one year after surgery. The paper is really interesting.

P- Reviewer: Naselli A, Soria F S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Cao D, Ma J, Yang X, Xiao J. Solitary juvenile xanthogranuloma in the upper cervical spine: case report and review of the literatures. Eur Spine J. 2008;17 Suppl 2:S318-S323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Janssen D, Fölster-Holst R, Harms D, Klapper W. Clonality in juvenile xanthogranuloma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:812-813. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Agabegi SS, Iorio TE, Wilson JD, Fischgrund JS. Juvenile xanthogranuloma in an adult lumbar spine: a case report. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36:E69-E73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dehner LP. Juvenile xanthogranulomas in the first two decades of life: a clinicopathologic study of 174 cases with cutaneous and extracutaneous manifestations. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:579-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 369] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Adamson HG. Congenital xanthoma multiplex. Br J Dermatol. 1905;17:222. |