Published online Sep 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.459

Revised: July 10, 2014

Accepted: July 18, 2014

Published online: September 16, 2014

Processing time: 151 Days and 1.6 Hours

Iliopsoas abscess (IPA) is an uncommon infection. The clinical presentation is usually insidious. Most patients present with nonspecific symptoms, leading to difficulty in prompt and accurate diagnosis. Delay in diagnosis can lead to complications, such as sepsis and death. Tattooing has become more popular over the recent years and has been associated with tattooing-related and blood-borne infections. We present two related cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus IPA after tattooing and review the epidemiology, etiology, clinical features, and management of IPA.

Core tip: Iliopsoas abscess (IPA), a collection of pus in the iliopsoas compartment, is classified as primary or secondary depending on the source of infection. While immunocompromise and intravenous drug abuse are the most common known risk factors for primary IPA, tattooing may represent a novel risk factor as well. We present two related cases of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus IPA after tattooing and review the epidemiology, etiology, clinical features, and management of IPA. Maintaining a high clinical suspicion for this condition in patients with risk factors is important for prompt and accurate diagnosis and prevention of complications, such as sepsis and death.

- Citation: Gulati S, Jain A, Sattari M. Tattooing: A potential novel risk factor for iliopsoas abscess. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(9): 459-462

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i9/459.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.459

Iliopsoas abscess (IPA) is a collection of pus in the iliopsoas compartment[1]. The unique anatomy of the psoas muscle predisposes it to infections by both direct extension and hematogenous spread[2]. The close proximity of the psoas muscle to sigmoid colon, jejunum, appendix, ureters, aorta, renal pelvis, pancreas, iliac lymph nodes, and spine makes it susceptible to contiguous spread of infections from these organs[3]. The abundant vascular supply of the muscle predisposes it to hematogenous spread of infections from occult sites[4]. The insidious onset and occult characteristics of IPAs can cause diagnostic delays and result in high mortality and morbidity[2].

A 48-year-old female with past medical history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and migraines presented with 4 d of abdominal and back pain, dysuria, nausea, and vomiting. She denied alcohol use, but admitted to cigarettes (34 pack-years) and previous intravenous (IV) drugs (most recent use 2 mo prior to presentation). Vitals included temperature of 98.3 degrees Fahrenheit, heart rate 103 beats per minute, blood pressure 138/84 mmHg, and respiratory rate 28 per minute. Physical exam was unremarkable. Laboratory data revealed a white blood cell count (WBC) of 34.6 × 103 cells per microliter, 92.8% neutrophils, 2% bands, hemoglobin of 12.4 g per deciliter, sodium of 135 mmol per liter, chloride of 97 mmol per liter, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) of 19 mg per deciliter, AST of 53 IU per liter, and ALT of 42 IU per liter. Urinalysis revealed cloudy urine with pH of 5.5, specific gravity of > 1.030, > 25 squamous epithelial cells, 11-17 WBC, 9-15 red blood cells, moderate bacteria, positive nitrites, negative leukocyte esterase, 2+ bilirubin, and 3+ urine protein, blood, and ketones. Urine toxicology screen was positive only for tricyclic antidepressants. Viral hepatitis panel was positive for Hepatitis C antibody. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) serology was negative. Initial blood gram stain revealed gram positive cocci in clusters, blood cultures grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), and urine culture remained negative. Vancomycin was initiated.

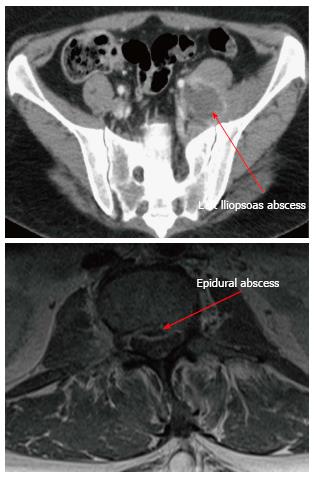

Transthoracic echocardiogram did not show evidence of endocarditis. Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast revealed abscess formation in the left posterior paraspinal muscles with retroperitoneal extension along the left iliopsoas and pelvis (Figure 1). Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of lumbar spine with and without contrast showed epidural abscess spanning the lumbar spine along the anterior epidural compartment (from T12 to S1), a small epidural abscess in the left posterolateral epidural compartment in the sacrum, left psoas abscess, left retroperitoneal abscess, left paraspinal abscess, a tiny intra psoas abscess on the right, and inflammatory changes in the right posterior paraspinal muscles without an associated abscess (Figure 1). Neurosurgery did not recommend surgical intervention. Interventional radiology performed CT-guided aspiration of the left paraspinal and left psoas abscesses, draining 14 and 15 milliliters of purulent material, which grew MRSA.

Interestingly, patient’s husband was also admitted to the same hospital at the same time and diagnosed with IPA due to MRSA. Our patient gave further history that her husband had used the same ink and equipment to tattoo his own arm and her back (Figure 2). Shortly afterwards, he had developed a superficial infection at his tattoo site which resolved prior to admission. Of note, comparison of MRSA isolated from our patient and her husband revealed identical sensitivities to antibiotics, suggesting the same strain (Table 1). Our patient was eventually discharged with outpatient IV antibiotics. At discharge, she was stable and afebrile with negative blood cultures and normal WBC.

| Antibiotic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 |

| Ciprofloxacin | Resistant | Resistant |

| Clindamycin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Daptomycin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Erythromycin | Resistant | Resistant |

| Gentamicin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Inducible Clindamycin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Levofloxacin | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Linezolid | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Minocycline | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Moxifloxacin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Oxacillin | Resistant | Resistant |

| Penicillin | Resistant | Resistant |

| Rifampin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Synercid | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Tetracycline | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Tigecycline A | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole | Sensitive | Sensitive |

| Vancomycin | Sensitive | Sensitive |

IPA is an uncommon infection[5]. There are two types of IPA: primary and secondary[2]. Primary IPAs are caused by hematogenous or lymphatic spread of bacteria, usually from occult distant sources[4]. While Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for the majority of primary IPAs[6], infections from other organisms such as Streptococci, Escherichia coli, Enterobacter, and Salmonella have also been reported[7,8]. Risk factors for primary IPAs include IV drug use (IVDU), HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, active malignancy, diabetes mellitus, receipt of steroids or chemotherapy, and renal failure[2,5]. Secondary IPAs result from local extension of adjacent sources of infection[5]. Risk factors for secondary IPAs include inflammatory or neoplastic diseases of the bowel, kidney, and spine, such as crohn’s disease, appendicitis, spinal pathology, trauma, or instrumentation in the groin, lumbar, or hip areas[3,4]. While secondary IPAs caused by Staphylococcus aureus have been reported[5], they are thought to be predominantly caused by enteric organisms, such as Escherichia coli, Enterobacter, Klebsiella, Streptococcus, Bacteroides, and Salmonella[3].

The clinical presentation of IPA is often variable. Symptoms are non-specific and include pain in back, abdomen, flank, hip, or thigh, as well as fever, limp, malaise, nausea, weight loss, and lump in the groin[2]. These unusual clinical features and subacute or chronic nature of symptoms may lead to delay in diagnosis[9]. Laboratory investigations may reveal leukocytosis, anemia, elevations in C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and BUN, as well as positive blood cultures[8,10]. While CT is considered the gold standard for definitive diagnosis[11], use of MRI has also been advocated because of better discrimination of soft tissues and the ability to visualize the abscess wall and surrounding structures without an intravenous contrast medium[12,13]. Characteristic radiographic features include focal hypodense lesion(s) within the psoas muscle, presence of gas within the muscle, and CT enhancement of the rim of the abscess with contrast[11]. In addition to confirming diagnosis of an IPA, imaging studies can demonstrate co-existing causative retro- or intra-peritoneal disease in secondary IPA[11].

Once IPA is diagnosed, treatment involves the use of appropriate antibiotics and drainage of the abscess[2]. If primary IPA is suspected, antibiotics with staphylococcal coverage should be selected[14]. In secondary IPA, broad spectrum antibiotics with both aerobic and anaerobic coverage should be considered[15]. Antibiotic therapy can subsequently be tailored to the results of the abscess fluid culture and sensitivity. Drainage of the abscess may be done percutaneously or surgically[2]. CT -guided percutaneous drainage is less invasive and has been proposed as the draining method of choice[16]. Surgical intervention for drainage can be considered in cases of failure of percutaneous drainage, multiloculated abscesses, inability or contraindication to undergo percutaneous drainage, or presence of surgical indication for another intra-abdominal pathology[2,17].

In our patient, radiological investigations led to the diagnosis, which was later confirmed by microbiological reports. While our patient was diagnosed with primary IPA, she did not have evidence of associated risk factors, such as HIV or active malignancy. Both she and her husband denied IVDU in the previous two months. Interestingly, there has been a previous case report of a patient developing IPA two months after cessation of IVDU[6]. However, our patient and her husband also reported sharing the same equipment for home-made tattoos. The identical antibiotic sensitivities of both patients’ MRSA strain as well as the reported superficial infection of husband’s tattoo site prior to developing IPA suggest that tattooing might have been the etiology of IPA development in these 2 cases. While the temporal relationship as well as biological plausibility makes this a possibility, we cannot confirm a causal relationship since we did not phenotype the MRSA strains or obtain environmental sampling (e.g., culture of the tattooing equipment).

This potential risk factor for IPA is important to recognize as tattooing has become more popular over the recent years. In 2012, 21% of adults in the United States had one or more tattoos, compared to 14% in 2008[18]. There have been reports of outbreaks of tattooing-related infections, including mycobacterial and MRSA infections from contaminated ink[18-20]. Tattooing is also associated with blood-borne infections such as Hepatitis C, independent of IVDU or blood transfusions prior to 1992[20]. It is conceivable that tattooing with potentially contaminated equipment caused transient bacteremia in our patient and her husband, leading to MRSA IPA. To our knowledge, IPA secondary to tattooing has not been reported in the literature. This case report demonstrates importance of recognition of tattooing as a possible risk factor for IPA, which along with maintaining a high clinical suspicion and meticulous clinical examination, can lead to prompt diagnosis, timely initiation of treatment, and reduction of morbidity and mortality.

A 48-year-old female presented with abdominal and back pain, nausea, and vomiting. Physical exam revealed fever, tachycardia, and tachypnea.

An inflammatory or infectious process involving the gastrointestinal (e.g., cholecystitis) or genitourinary system (e.g., pyelonephritis).

Labs were only remarkable for leukocytosis, elevated BUN, mild transaminitis, and abnormal urinalysis.

Computed tomography (CT) of abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast revealed iliopsoas abscess (IPA). CT-guided aspiration of the IPA drained purulent material, which grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Patient was treated successfully with a prolonged course of intravenous vancomycin.

Very well documented. Excellent diagnostic approach and treatment. Important description of potential risks from the tattooing process, expecially when strict antiseptic measures are not followed.

P- Reviewer: Fett JD, Wong OF S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Mynter H. Acute psoitis. Buffalo Med Surg J;. 1881;202-210. |

| 2. | Mallick IH, Thoufeeq MH, Rajendran TP. Iliopsoas abscesses. Postgrad Med J. 2004;80:459-462. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Tasci T, Zencirci B. A female presenting with prolonged fever, weakness, and pain in the bilateral pelvic region: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:194. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Adelekan M. A review of psoas abscess. Afr J Clin Exp Microbiol. 2004;5 Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/ajcem.v5i1.7360. |

| 5. | Alonso CD, Barclay S, Tao X, Auwaerter PG. Increasing incidence of iliopsoas abscesses with MRSA as a predominant pathogen. J Infect. 2011;63:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Olson DP, Soares S, Kanade SV. Community-acquired MRSA pyomyositis: case report and review of the literature. J Trop Med. 2011;2011:970848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ricci MA, Rose FB, Meyer KK. Pyogenic psoas abscess: worldwide variations in etiology. World J Surg. 1986;10:834-843. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Santaella RO, Fishman EK, Lipsett PA. Primary vs secondary iliopsoas abscess. Presentation, microbiology, and treatment. Arch Surg. 1995;130:1309-1313. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Vaz AP, Gomes J, Esteves J, Carvalho A, Duarte R. A rare cause of lower abdominal and pelvic mass, primary tuberculous psoas abscess: a case report. Cases J. 2009;2:182. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Taiwo B. Psoas abscess: a primer for the internist. South Med J. 2001;94:2-5. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Zissin R, Gayer G, Kots E, Werner M, Shapiro-Feinberg M, Hertz M. Iliopsoas abscess: a report of 24 patients diagnosed by CT. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:533-539. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Qureshi NH, O’Brien DP, Allcutt DA. Psoas abscess secondary to discitis: a case report of conservative management. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:73-76. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Wu TL, Huang CH, Hwang DY, Lai JH, Su RY. Primary pyogenic abscess of the psoas muscle. Int Orthop. 1998;22:41-43. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Gruenwald I, Abrahamson J, Cohen O. Psoas abscess: case report and review of the literature. J Urol. 1992;147:1624-1626. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Bresee JS, Edwards MS. Psoas abscess in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1990;9:201-206. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Cantasdemir M, Kara B, Cebi D, Selcuk ND, Numan F. Computed tomography-guided percutaneous catheter drainage of primary and secondary iliopsoas abscesses. Clin Radiol. 2003;58:811-815. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Wong OF, Ho PL, Lam SK. Retrospective review of clinical presentations, microbiology, and outcomes of patients with psoas abscess. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19:416-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | LeBlanc PM, Hollinger KA, Klontz KC. Tattoo ink-related infections--awareness, diagnosis, reporting, and prevention. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:985-987. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kennedy BS, Bedard B, Younge M, Tuttle D, Ammerman E, Ricci J, Doniger AS, Escuyer VE, Mitchell K, Noble-Wang JA. Outbreak of Mycobacterium chelonae infection associated with tattoo ink. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1020-1024. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Carney K, Dhalla S, Aytaman A, Tenner CT, Francois F. Association of tattooing and hepatitis C virus infection: a multicenter case-control study. Hepatology. 2013;57:2117-2123. [PubMed] |