Published online Sep 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.439

Revised: June 27, 2014

Accepted: July 25, 2014

Published online: September 16, 2014

Processing time: 148 Days and 17.6 Hours

AIM: To study a service model that enables a clinic to be open to all members of the community, irrespective of their ability to pay.

METHODS: Sampling methodology was used to gather information in two phases, with the city of Indore as the target region. In the first phase, dental professionals were surveyed to gather the cost of the facility, land and equipment and the cost of sustaining the practice. In the second phase, the residents of Indore were surveyed to collect information regarding their oral health problems and their expenditure for the same. Assessing the current situation, the questions to answer are related to the issues of dental health care access problems and the resources required, human and financial.

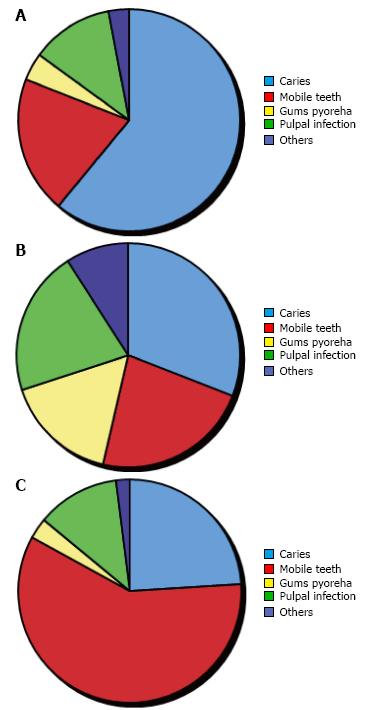

RESULTS: (1) People younger than 20 years of age form a large proportion (43%) of the population of the city and also a large proportion (54%) of people who visit dental clinics; (2) Dental caries are commonly found in the population younger than 20 years of age and mobile teeth in those older than 50 years of age; (3) Dental caries and mobile teeth are almost equally found in people of the age group 20-50 years old; (4) A significantly large proportion of those older than 50 years old have had all their teeth extracted; and (5) A significantly large proportion of the 20-30 years of age group has had no teeth extracted.

CONCLUSION: The model which we propose works well for low income patients; however, it places a lot of extra burden on the higher income group. A lot of effort can be put into generating revenue from other sources, including events and donations.

Core tip: One of the primary reasons for the challenges faced by dental health care in a developing country like India is that when primary health care systems were being implemented, dental health care was not included. Also, although expenditure on health care systems form a significant percentage of the gross domestic product (nearly 5%), it is very small compared to the total population of the country. On top of that, the amount of money spent on dental health care is less compared to some other nations. This has left dental health care in India far behind other health services. The following are some of the challenges faced by dental health care in India: (1) expensive treatment; (2) imbalanced distribution of clinics; (3) unawareness; (4) skewed population to dentist ratio; and (5) changing disease pattern and treatment needs. People in developing regions suffer from different types of dental diseases, which are curable with treatment but not affordable by most people. In this study, a service model was developed that enables a clinic to be open to all members of the community, irrespective of their ability to pay.

- Citation: Sugandhi A, Mangal B, Mishra AK, Sethia B. To explore and develop a model to maintain and build upon a dental clinic open for all in developing regions, with a primary focus on India. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(9): 439-447

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i9/439.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.439

In developing nations such as India, 70% of people live in rural areas and nearly 35% of population is below poverty line. In 2004-2005, around 39 million (30.6 and 8.4 million in rural and urban areas, respectively) of Indians fell into poverty as a result of out of pocket expenditures each year[1,2]. People do not have funds for eating, let alone dental and other medical health care. The impact of health expenditures are greater in rural areas and in poorer states where a greater proportion of the population live near the poverty line[2]. The total expenditure on health was estimated to be 4.13% of the gross domestic product (GDP) in 2008-2009, with public expenditure on health at 1.10% of the share of GDP[3]. Private expenditures on health have remained high over the last decade[4]. A greater proportion of resources are directed towards urban-based services and higher level services, with 29.2% of public expenditures (both central and state) allocated to urban allopathic services compared to 11.8% of public expenditures allocated to rural allopathic services in 2004-2005. This imbalanced allocation is compounded by the private sector’s bias toward higher level curative services which, determined by market forces, tends to be centered in wealthier urban areas[5]. Most public health facilities lack efficiency, are understaffed and have poorly maintained or outdated medical equipment. In addition to the lack of funds and poor infrastructure, India faces a shortage of medical staff for these facilities, especially in rural regions where access to medical care is limited. Thus, it is important to build a model clinic that does not attempt to segregate the poor but is open to all with a sliding-fee schedule to make dental care affordable for the poor and uninsured.

Development of a country is measured with the help of statistical indexes, such as per capita income (GDP), life expectancy, the rate of literacy, educational attainment, etc. The UN developed the Human Development Index (HDI)[6], a standard mean of measuring human development. Thus, it helps to determine whether a country is a developed, developing or underdeveloped country.

A developing country has a low standard of democratic government, industrialization, social programs and human rights guarantees. In other words, it can be said that a developing country has an undeveloped or developing industrial base and an inconsistent varying HDI. However, countries that have more advanced economies than other developing nations but have not fully demonstrated the signs of a developed country are called newly industrialized countries. Countries that have sustained good economic growth over a long period of time and have a good economic potential are termed emerging markets. India falls under this category of big emerging markets, the target of this study.

Over the years, the Indian economy has grown a lot but differences between the rich and poor have widened. In India, the government and private sector provide health care jointly. The poor who were not able to afford expensive medical treatment earlier are still not able to afford it. Since oral health care is still in the developing stage in India, it is expensive compared to other medical treatments, putting it out of the reach of the common man. Private sector hospitals are primarily motivated by profit, thus leaving a majority of population unattended to with public health institutions as the only hope for such underprivileged people. Since these people form a large chunk of the Indian population (over 35%), the cost of treatment becomes all the more important.

One of the primary reasons for the challenges faced by dental health care in India is that when primary health care systems were being implemented, dental health care was not included. Also, although expenditure on health care systems forms a significant percentage of the GDP (nearly 5%), it is very small compared to the total population of the country. On top of that, the amount of money spent on dental health care is much less compared to some other nations. This has left dental health care in India far behind other health services. The following are some of the challenges faced by dental health care in India.

Expensive treatment: The increasing cost of oral healthcare that is paid as “out of pocket” payments makes oral healthcare unaffordable for a growing number of people. The number of people who could not seek oral care because of a lack of money increased significantly between 1986 and 1995 and the proportion of people unable to afford basic oral healthcare has doubled in the last decade. Over 20 million Indians are pushed below the poverty line every year because of the effect of out of pocket spending on health care[7].

Imbalanced distribution of clinics: In India, up to 80% of the population lives in rural areas without any access to dental health care[8]. Community oriented health programs are seldom found in rural areas. For any type of dental health care, they need to go to urban areas, thus compounding the cost of treatment, which makes them unwilling to go for treatment.

Unawareness: It has been found that 30% of population were unaware of the ideal ways of avoiding tooth decay, gum diseases and oral cancer[9]. Only a small number of people go to a dentist on a regular basis or even in a medical emergency.

Skewed population to dentist ratio: The current dentist to population ratio in India is 1:10000[10] in urban and 1: 2.5 lakh in rural areas[11]. This is a significant improvement from the 1980s when it was 1:80000. However, with the geographical imbalance of the situation of dental colleges, the ratio varies significantly in rural and urban areas.

Changing disease pattern and treatment needs: The effectiveness of preventive dentistry is leading to a change in the disease pattern as well as people becoming more aware and concerned about dental health care. Although this number is small it is increasing, thus it has led to a decrease in demand for tooth extraction to an increase in demand for conservative modalities, such as root canal treatment. This puts a lot of pressure on an already stressed out system to introduce different specializations in postgraduate courses.

The cost of treatment is one of the major concerns of the Indian population, forcing them to avoid treatment if at all possible. The following are some of the major reasons for the high cost of dental treatment in India: (1) a skewed dentist to population ratio, leading to a high demand for care; (2) rapidly changing technology and the cost to keep up with it; (3) more remuneration for qualified professionals; (4) high demand for better care; and (5) a large aging population needing special attention.

Primary objective: The primary objective is to explore and develop a model to maintain and build upon a dental clinic open for all in the developing regions, with a primary focus on India.

Secondary objective: The secondary objectives are: to study the challenges in dental health care in India; to study the cost of setting up and maintaining a dental health care clinic; to study the common dental ailments prevailing in Indian patients; and to study the needs of different types of patients.

The underlying challenge to our study was to understand how to achieve a balance between providing dental care to low income patients and financial stability of the clinic. Thus, factors that affect patient care revenue, including the start-up and maintenance cost, needed to be assessed. This sequence of steps was followed to achieve this goal: (1) in assessing the current situation, the questions related to dental health care access problems and human and financial resources required need to be answered; and (2) the need to envision the desired solution and define what is to be achieved.

All our studies and surveys were carried out in the city of Indore, the most populous city in Madhya Pradesh, with a population of about 3600000[12]. Its population is a mix of low and high income. Although there are no specific data regarding the income of people in Indore, a survey of the population of Madhya Pradesh indicated that 38% of the urban population[13] lives below the poverty line. Thus, assuming that this data can be extended to the population in Indore, this number is a significantly large proportion of the population. There are four dental colleges and several public and private dental clinics around the city.

As a first step, the needs of a dental clinic were determined. The assessment considered the following factors: (1) population demographics: collecting information regarding poverty, age and insurance is helpful to provide a perspective about the underlying population as dental disparities occur in many population subgroups. This information is available in the 2001 census of India[14] (Table 1); (2) dental needs of the target population; (3) accessibility of current dental care resources for the target population, including availability and utilization of public and private dental care units; and (4) community perceptions of the need for dental care resources.

| Variable | n (%) |

| Population | |

| Total | 2465827 (-) |

| Males | 1289352 (53) |

| Females | 1176475 (47) |

| Rural | 735464 (29.7) |

| Males | 379624 (15.3) |

| Females | 355840 (14.4) |

| Urban | 1730363 (70.3) |

| Males | 909728 (36.9) |

| Females | 820635 (33.4) |

| Age Distribution | |

| < 10 yr | 538943 (21.8) |

| 10-20 yr | 524116 (21.2) |

| 20-30 yr | 460948 (18.6) |

| 30-50 yr | 625071 (25.3) |

| > 50 yr | 309070 (12.5) |

In order to determine the dental needs of the people of Indore and status of the current dental health care in the city, a survey at four medical hospitals and several dental clinics was conducted to collect responses from 40 dentists across the city. The survey included a questionnaire (Table 2) to be filled in by the dentist.

| Age group | % |

| 1 Percentage distribution of different age groups that have visited the dentist in the previous year | |

| < 10 yr | |

| 10-20 yr | |

| 20-30 yr | |

| 30-50 yr | |

| > 50 yr | |

| 2 Percentage distribution of different age groups needing dental treatment according to urgency of need | |

| < 10 yr | |

| 10-20 yr | |

| 20-30 yr | |

| 30-50 yr | |

| > 50 yr | |

| 3 Percentage distribution of children < 20 yr of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | |

| Mobile teeth | |

| Gums pyorrhea | |

| Pulpal infection | |

| Others | |

| 4 Percentage distribution of people between 20-50 yr of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | |

| Mobile teeth | |

| Gums pyorrhea | |

| Pulpal infection | |

| Others | |

| 5 Percentage distribution of people above 50 yr of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | |

| Mobile teeth | |

| Gums pyorrhea | |

| Pulpal infection | |

| Others | |

| 6 Percentage of different age groups who had all their teeth extracted | |

| < 10 yr | |

| 10-20 yr | |

| 20-30 yr | |

| 30-50 yr | |

| > 50 yr | |

| 7 Percentage of different age groups who had no teeth extracted | |

| < 10 yr | |

| 10-20 yr | |

| 20-30 yr | |

| 30-50 yr | |

| > 50 yr | |

The survey was carried out to identify the dental health care needs and problems of different age groups and to identify the minimum level of care needed to be provided at the clinic.

The following section summarizes the results of the survey.

Tables 3-6 and Figures 1-2 contain an average of the responses received from various sources for questions 1-7 in the survey (Table 2). The results from the data are: (1) people < 20 years of age form a large proportion (43%) of the population of the city and a large proportion (54%) of the people who visit dental clinics; (2) dental caries is the most widespread dental disease (or ailment) faced by the population < 20 years of age; (3) mobile teeth is the most wide spread disease (or ailment) faced by the population > 50 years of age; (4) dental caries and mobile teeth are almost equally found in people in the 20-50 years of age group and together they form the most widespread disease (or ailment) in the age group; (5) A significantly large proportion of the > 50 years age group has had all their teeth extracted; and (6) a significantly large proportion of the 20-30 years age group had no teeth extracted.

| Age group | % |

| < 10 yr | 23 |

| 10-20 yr | 31 |

| 20-30 yr | 19 |

| 30-50 yr | 16 |

| > 50 yr | 11 |

| Age group | % |

| < 10 yr | 15 |

| 10-20 yr | 24 |

| 20-30 yr | 13 |

| 30-50 yr | 19 |

| > 50 yr | 29 |

| Disease | % |

| Children < 20 yrs of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | 61 |

| Mobile teeth | 20 |

| Gums pyorrhea | 4 |

| Pulpal infection | 12 |

| Others | 3 |

| People between 20-50 yrs of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | 34 |

| Mobile teeth | 25 |

| Gums pyorrhea | 18 |

| Pulpal infection | 23 |

| Others | 10 |

| People above 50 yrs of age with the following diseases or dental ailments | |

| Caries | 24 |

| Mobile teeth | 59 |

| Gums pyorrhea | 3 |

| Pulpal infection | 12 |

| Others | 2 |

| Age group | % |

| Different age groups who had all their teeth extracted | |

| < 10 yr | 3 |

| 10-20 yr | 4 |

| 20-30 yr | 3 |

| 30-50 yr | 7 |

| > 50 yr | 42 |

| Different age groups who had no teeth extracted | |

| < 10 yr | 21 |

| 10-20 yr | 33 |

| 20-30 yr | 67 |

| 30-50 yr | 8 |

| > 50 yr | 2 |

Based on these results, the following level of service to be provided at the clinic was identified.

Services are provided early in the disease process which limits the disease from progressing further. These include diagnostic procedures, simple restoration of diseased teeth, early treatment of periodontal disease and many surgical procedures needed to treat oral pathologies.

These include the services which prevent the onset of the dental disease process.

The next step was to estimate the expenses of a dental clinic. We conducted another survey (Table 7) to estimate start up and operational cost of a dental clinic. This survey was conducted with the suppliers for each of these commodities to determine the costs and dentists were asked about average operational costs. Table 8 summarizes the result of the expense survey.

| Expense | Cost |

| Start-up costs | |

| Construction (or remodeling cost) | |

| Dental equipment cost (including supplies and instruments) | |

| Furniture | |

| Record filling system | |

| Phone / intercom system | |

| Computer / data / billing | |

| Operating Expenses | |

| Dental assistant | |

| Billing Clerk (or Secretary or Receptionist) | |

| Clinical supplies | |

| Office supplies | |

| Equipment maintenance | |

| Housekeeping | |

| Laundry | |

| Communications | |

| Equipment reserve fund | |

| Expense | Cost |

| Start-up costs | |

| Construction (or remodeling cost) | Rs. 1205000 |

| Dental equipment cost (including supplies and instruments) | Rs. 924500 |

| Furniture | Rs. 45900 |

| Record filling system | Rs. 12500 |

| Phone /intercom system | Rs. 9300 |

| Computer/data/billing | Rs. 35200 |

| Total start-up costs | Rs. 2232400 |

| Operating expenses | |

| Dentist | Rs. 750000 |

| Dental assistant | Rs. 24000 |

| Billing clerk (or secretary or receptionist) | Rs. 5000 |

| Clinical supplies | Rs. 107900 |

| Office supplies | Rs. 12500 |

| Equipment maintenance | Rs. 21400 |

| Housekeeping | Rs. 13600 |

| Laundry | Rs. 26700 |

| Communications | Rs. 24000 |

| Equipment reserve fund | Rs. 10000 |

| Total operating expenses | Rs. 995100 |

| Total expenses | Rs. 3227500 |

The equipment reserve fund is the money set apart for buying expensive equipment in the future. The list of essential dental equipment (Table 9) was determined from a list of the supplies and instruments from a dental clinic in Indore. As well as these dental instruments and supplies, a dental chair is also present at the clinic.

| Operative Instruments | Handpieces | Other instruments | Operative supplies | Disposables | Infection control supplies | Standard oral surgery kit | Oral surgery instruments | Oral surgery supplies |

| Mouth Mirrors #5 | High-Speed Handpiece | Dental Mirrors #5 for Exam Kits | Lidocaine 2% 1: 100000 epi/can | Tray Covers -Mauve lOOO/Box | Latex Exam Gloves, pick size | Surgical Handles, #3 | 150 Forceps | 3-0 Silk Sutures, 18” Cutting, Needle C-6 12/Box |

| Mirror Handles | Low-Speed Handpiece | Mirror Handles for Exam Kits | 3% Mepivicaine/can | 2 x 2 gauze 8 ply 200/Pkg | Sterile Surgeons Gloves, pick size | #9 Molt Periosteal Elevator | 151 Forceps | 3-0 Chromic Gut Sutures, 27”, C-6 12IBox |

| 23 Explorer/PSR | Ball-Bearing Contra Angle Assembly (Latch) | Explorer/PSR Periodontal Probes for Exam Kits | 5% Marcaine 1:200000 epi/can | 4 x 4 gauze 8 ply 200/Pkg | Utility Gloves, Large | Needle Holder, Crile-Wood 6 inch | 17 Forceps | Biopsy Bottles |

| Scissors, Iris 41/2" Straight, Economy | Prophy Contra Angle Head Assembly | Cement Spatulas #24 | 27 gauge Long Needles/box | Dry-Gard Patient Bibs (rose) 500/Case | Face Masks, 50 per box | 301 Elevator | 23 Forceps | Dry Socket Paste, 1 oz |

| Cotton Pliers(s), College #317 | Contra Angle Sheath | Aspirating Syringe CW Type | 30 gauge Short Needles/box | Napkin Holder | Safety Glasses | 34 Elevator | 88R Forceps | Iodoform Gauze 1f4”× 5 yd |

| Spoon Excavator #38-39 | Straight Attachment | Composite Instruments, Set of 3 | Topical Anesthetic | Cotton Tip Applicators 6” non-sterile lOOO/Box | Disposable Cover Gowns, pick size | Minnesota Retractor | 88L Forceps | Gelfoam |

| Amalgam Carrier Double Ended I | Spray and Clean Handpiece Lubricant | Rubber Dam Punch | Sharps Container | Cotton Pellets #2 2000/Box | Antiseptic Hand Soap, | Curette | #1 Forceps | #15 Blades 100/Box |

| Amalgam Plugger l/2 Black | Rubber Dam Clamps, Starter Kit | Accu Film II/box | Cotton Pellets #4 3000/Box | Cleaning Solution | Kelly Hemostats, Curved 51/2” | Cryer 30 | ||

| Cleoid-Discoid 89/92 | Amalgam -Regular Set/can | Cotton Rolls 2000/Box | Banicide Plus, 3.4% Glutaraldehyde, 1 Gallon | Mouth Mirror 1 Mouth Handle | Cryer 31 | |||

| Cleoid-Discoid 3/6 | Glass Ionomer Kit | Cotton Roll Dispenser | Disinfectant | Scissors Kelly 61/4”, Curved | Crane Pick | |||

| Hollenbach | IRM Caps 50/Pkg. | Plastic Cups, 1OOO/Case | Self Seal Sterilization Pouches 31/2”× 9” | Mouth Prop (adult) 2/Box | Periosteal Elevator #9 Molt | |||

| Interproximal Carver | Clear Matrix Strips/box | Cup Holder | Self Seal Sterilization Pouches 31/2”× 51/4”, | Suction Tips | Heidbrink #1 Root Tip Pick | |||

| Articulatiilg Paper Forceps | Sof-Lex Pop-On Kit #1980 | Safe-Tips EZ 150/Pouch | Self Seal Sterilization Pouches 51/4”× 10” | Heidbrink #2 Root Tip Pick | ||||

| Rubber Dam Frame | Finishing Strips Coarse/Medium 150/Box | High Speed Evacuation Tips SO/Bag | Self Seal Sterilization Pouches 71/2 × 13”, | Heidbrink #3 Root Tip Pick | ||||

| Rubber Dam Clamp Forceps | Lightening Strips Medium 12/tube | Saliva Ejectors White Opaque 100/Bag | Chair Covers 48”× 56" | Tissue Forceps | ||||

| Dycal Instrument | Polishing Paste/can | Dappen Dishes lOOO/Box | Air/Water Syringe Covers | Rongeurs | ||||

| Tofflemire(s) 2 per kit, universal | Toillemire Matrix Bands #1, .0015 12/Pkg | Oral Evacuation Cleaner | Light Handle Covers | Bone File, 12 Howard | ||||

| Tofi1emire Matrix Bands #2 .0015 12/Pkg | Disposable Spatulas l00/Box | ALLRAP 1200 Sheets/Roll | Straight Hemostat, Crile 51/2” | |||||

| Dycal Ivory Shade/tube | Benda Brush 144/Box | Mouth wash, may want to order pump | Needle Holder, Crile-Wood | |||||

| Copalite 1/2oz/bottle | Disposable Mirrors 72/Box | Periogard 16 oz | Surgical Handle | |||||

| Vitrebond 3M/box | Disposable Traps Dental Unit 144/Box, pick size needed | Cure Sleeve, Steri Shield 5OO/Box | Dental Mirror for Post-Op Kit | |||||

| Disposable Traps Central Suction 8/Box, pick size needed | Tube Sleeve 2” | Mirror Handles for Post-Op Kit | ||||||

| Paper Towels | X-ray sleeve 14” W × 13” D x 241/2” L | Iris Scissors for Post-Op Kit | ||||||

| Biological Monitoring System Biological Indicators (25/box) | Cotton forceps for Post-Op Kit |

In order to design a sliding fee model, the expected revenue from the clinic should be known in order to be able to sustain the clinic. Thus, a survey was conducted (Table 10) to determine the revenue from the clinic from sources at all the hospitals and clinics where the first survey was conducted. Table 11 contains the results of dental clinic revenue survey.

| Source | Income |

| Patient care revenue - self pay | |

| Patient care revenue - insurance | |

| Patient care revenue - total | |

| Donations and other sources | |

| Individual donations | |

| Corporate donations | |

| Events | |

| Source | Income |

| Patient care revenue | |

| Patient care revenue – self pay | Rs. 866050 |

| Patient care revenue – insurance | Rs. 166450 |

| Patient care revenue – total | Rs. 1032500 |

| Donations and other sources | |

| Individual donations | Rs. 9000 |

| Corporate donations | Rs. 13000 |

| Events | Rs. 6000 |

| Donations – total | Rs. 28000 |

| Total revenue (all sources) | Rs. 1060500 |

While calculating the expense of a clinic, we observed that the initial cost of starting the clinic was a major component (nearly 66%). Thus, the question was asked if it was necessary to have a fixed dental clinic or if a mobile clinic was sufficient, thus reducing the initial start-up cost. Mobile clinics are used to serve small pockets of patients scattered over a geographic area. The greatest advantage of such a clinic is that initial cost of setup is low but the future cost of maintenance is high and the life of a mobile facility is shorter than a fixed facility. One of the aims of the open-to-all clinic is to provide care to as many people as possible so as to maximize the revenue, which would be otherwise difficult in a mobile clinic. Thus, it makes more sense to have a fixed facility that can serve a large number of people.

Once we had determined the expenses and revenue of a dental clinic had been determined, the next step was to develop a sliding fee model for patient charges, which was our initial goal. However, to build such a model we still needed information such as the average number patients from different income groups who visit dental clinics (Table 12). Another survey was conducted to determine this and the results are presented in Table 13.

| Variable | Value |

| Patient Visits | |

| Total number of patient visits: | |

| Well off patients1 | |

| Low income patients2 | |

| Patients with insurance | |

| Per patient visit charge | |

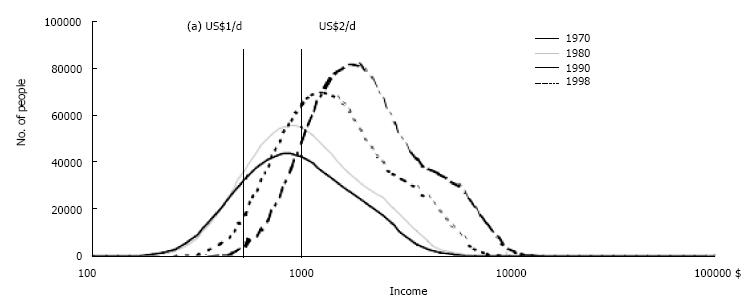

After gathering all the relevant data, a sliding fee model that can be used for a dental clinic in India was developed. Figure 3 shows a graph from the G20 report[15] on poverty and inequality, showing the distribution of population and their income. It can be seen that less than one-fifth of the population lies below the two dollar (Rs. 100) line and around 1% lies below the one dollar (Rs. 50) line. The maximum percentage of the population earns close to Rs. 300-350 (per day).

The per visit charge for patients was determined, which was taken as the basis for providing a discount to the low income group. This had to be greater than the average per visit charge we estimated from our survey in order to sustain the clinic financially. The extra amount of money being charged to the high income group will help to subsidize the fees for the low income group. The population was then divided into five different groups on the basis of their income: (1) low income group, earning < Rs. 100/d; (2) lower-middle income group, earning > Rs. 100 but < Rs. 300/d; (3) middle income group, earning > Rs. 300 but < Rs. 400/d; (4) higher-middle income group, earning > Rs. 400 but < Rs. 1000/d; and (5) higher income group, earning > Rs. 1000/d.

Well off patients (including the higher middle and higher income group) constitute a significant proportion of the population that visits dental clinics (Table 13) and is nearly thrice as large as the low income patients that visit dental clinics. So, in order to provide X% discount to the lower income group, X /3% more is charged to the higher income group. The baseline charge of Rs. 400 per visit is fixed. It was estimated that the low income group would form approximately 10% of the total patients, lower middle income group nearly 16%, middle income nearly 35%, higher middle income nearly 22% and higher income nearly 17% of the total population. Discounts are now provided to various income groups (Table 14).

| Income group | Discount |

| Lower income | 75% |

| Lower-middle income | 50% |

| Middle income | 12.50% |

| Higher-middle income | 0% |

| Higher income | -75% |

The bottom line in establishing various discounts is that the weighted sum of the discount and proportion of the population that group forms should not be negative if the clinic is to be sustained financially. The sliding fee schedule is used by totaling the full fees, multiplying the discount factor and subtracting to determine the charge to the patient. Note that the negative discount for the higher income group means that they have an extra fee compared to the other income groups. There are fees for cases that would not be discounted in the case of a very high cost of treatment to the higher income group or giving a very large discount to a lower income group.

These dental clinics address dental access problems and barriers in several ways and should be distributed throughout the state in urban and rural locations. They will serve communities for many years and maintain adequate hours of practice. Such dental clinics provide the most common dental services and, when additional services are needed, referrals to dental colleges are made. The clinic treated low income patients living below the poverty line at a very low cost and also treated low middle and middle income group patients with a sufficient discount. Because most of the clinics are located within facilities that provide oral health care service at very low cost, especially for the low income group, patients might perceive them as being more accessible and familiar. This assistance and familiarity will reduce important nonfinancial access barriers. These dental clinics will offer a variety of oral health outreach and educational programs designed to reach broader groups and expand the oral health message, possibly preventing further dental problems.

In this study, it was found that the middle and higher income group constituted a significant portion of the population who visit the dental clinic, about thrice as large as the low income group, according to the result of survey given in Table 13. So, by giving 1/3% of discount to low income group, a better oral health service is provided for them (Table 14). The almost 75% discount to the low income group and 50% discount to lower middle income group allows problem free thinking in approaching oral health care. A slightly higher fee is charged to patients with insurance to increase revenue and reduce the burden on the higher income group patients. The study limitations are that the higher income group is charged an extra fee compared to other income groups.

One of the important aims of developing such a clinic was to provide dental care to low income populations who have poor access to health care. However, it should not be forgotten that a clinic is of no use if it cannot keep its door open. The more inclusive a clinic seeks to be in providing access, the greater the risk of operating in the red because of uncompensated care. By the same token, the more a clinic limits uncompensated care, the greater its risk of limiting access to dental care for people with low income. Thus, it is always important to achieve a balance between the two. The model which we have proposed in Table 14 works well for low income patients in terms of providing them dental care at low and affordable cost; however, it places a lot of extra burden on the higher income group, which may not be acceptable to them. In this case, effort can be put into generating revenue from other sources, including events and donations.

This model has been used to open a dental clinic in a developing region in India, providing access irrespective of the patient’s ability to pay. So far, however, no such survey has taken place before opening a dental clinic in which both lower income and higher income group are considered.

The model given is good for giving dental care at low and affordable cost to the low income group but it places an extra burden on the higher income group which may not be acceptable to them.

This is a pioneering study in which the authors used sampling methodology for a survey conducted in two phases. The first phase was to ascertain the cost of the facility, land and equipment and the cost of sustaining the practice. In the second phase, a survey of the residents of Indore was carried out to collect information regarding their oral health problems and their expenditure for the same.

In developing regions like India, this model may have success for people with low income and the extra burden on the higher income group can be distributed by generating funds by events and donations.

GDP: Gross Domestic Product; HDI: Human Development Index.

The paper is acceptable in its current form.

P- Reviewer: Oji C, Ozcan M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Selvaraj S, Karan A. Deepening Health Insecurity in India: Evidence from National Sample Surveys since 1980s. E PW. 2009;44:55-60. |

| 2. | Garg CC, Karan AK. Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: a disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:116-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | India Go. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare; 2009. India: National Health Accounts, 2004- 2005; . |

| 4. | National Health Accounts, 2009 [EPB003(9-10)_WHO_India_National 1 1]. India: National Health Accounts, 2004-; . |

| 5. | Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV. Health care and equity in India. Lancet. 2011;377:505–511. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 667] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Balarajan Y; UNDP. Human Development Report, 2010. New York, USA: United Nations Development Programme 2010; . |

| 9. | Bhat KP, Kumar A, Aruna CN. Preventive oral health knowledge, practice and behaviour of patients attending dental institution in Bangalore, India. J Int Oral Health. 2010;2. |

| 10. | Ahuja NK, Parmar R. Demographies & current scenario with respect to dentist, dental institutions & dental practice in India. Ind J Dent Sciences. 2011;2: 8-14. |

| 11. | Tandon S. Challenges to the oral health workforce in India. J Dent Educ. 2004;68:28-33. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Census of India. Madhya Pradesh: Directorate of census operations; Ministry of Home affairs, 2011. Available from: http: //www.censusindia.gov.in/2011-prov-results/data_files/mp/00-1PPT_Madhya P_cover.pdf]. |

| 13. | SP Batra, Chitranjan singh and Mangesh tyagi. District wise poverty estimates for Madhya Pradesh; Poverty Monitoring and Policy Support Unit, 2004-05. [. Available from: http: //mpplanningcommission.gov.in/international-aided-projects/pmpsu/outputs to be upload 08.11.10/District Wise Poverty Estimates.pdf]. |

| 14. | Census of India. . Madhya Pradesh: Directorate of census operations. : Ministry of Home affairs 2001; . |

| 15. | Xavier Sala-i-Martin, Mohapatra Sanket. Poverty, inequality & the distribution of income in the group of 20; Dept of Economics: Columbia university, 2002 [. Available from: http://archive.treasury.gov.au/documents/580/HTML/docshell.asp?URL=Poverty_Inequality.asp]. |