Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.927

Revised: September 18, 2014

Accepted: October 1, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 176 Days and 15.9 Hours

A 49-year-old female patient consulted us for a cardiac evaluation before undergoing colon adenocarcinoma surgery. Three years prior, the patient underwent coronary angiography for dyspnea. The coronary angiography examination revealed a fistula originating from the left anterior descending artery and left main coronary artery, which had soft aneurysmal sacs and most likely drained into the pulmonary artery. Parasternal short axis echocardiography revealed a color flow that could be related to the fistula, but the other echocardiographic findings were normal. The patient did not accept the proposed examination and invasive treatment.

Core tip: (1) Acquire technical and surgical skills; (2) Learn the coronary anatomy and its variations; and (3) Learn the methodology of for treating coronary anomalies.

- Citation: Emre E, Aktas M, Sahin T, Ural E, Ural D. Rare multiple fistulas with large saccular aneurysms originating from left anterior descending artery and left main coronary artery. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(12): 927-929

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i12/927.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.927

Coronary artery fistulas are rare anomalies that open into the heart chambers, large vessels and other structures by bypassing the myocardial capillary network. Coronary artery fistula is detected in 1.21%-5.60% of all patients undergoing coronary angiography[1]. Left main coronary artery fistula is extremely rare[2]. Not all coronary-pulmonary artery fistulas are hemodynamically significant, however some may cause myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary arterial hypertension, aneurysmal fistula rupture and sudden death[3]. Here we present a case with an angiographically documented coronary artery fistula that originating from the left main coronary artery (LMCA) and dividing into two branches. In addition, another fistula that originated from the left anterior descending artery (LAD) combined with the LMCA fistula and created a new line of fistula, with large saccular coronary sacs, that drained into the pulmonary artery. This type of coronary artery fistula is most rares.

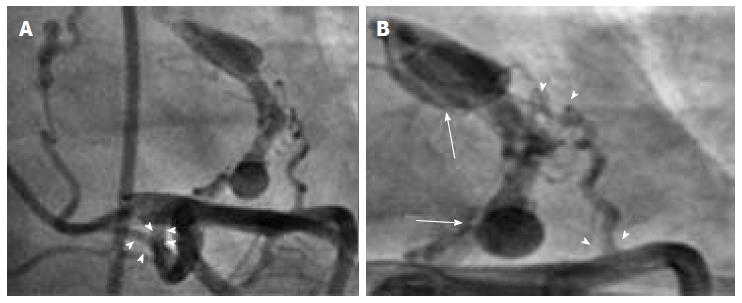

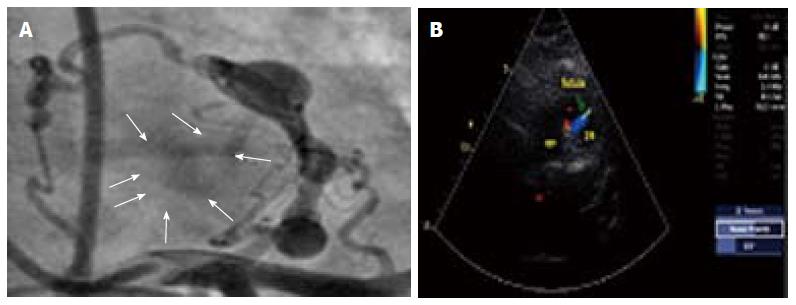

A 49-year-old female patient consulted us for a cardiac evaluation before undergoing colon adenocarcinoma surgery. Three years prior, the patient underwent coronary angiography for dyspnea. The coronary angiography examination revealed, a fistula originating from the LMCA which could be interpreted as draining into the pulmonary artery. Upon examining the coronary angiography in detail, in addition to the LMCA fistula, another fistula emerged from the LAD combined with the LMCA fistula and there was an aneurysmal sac swinging on fistula line (Figure 1). It was thought that the fistula was draining into the pulmonary artery (Figure 2A). Parasternal short axis echocardiography revealed a flow that was most likely caused by the fistula (Figure 2B). There were no regional wall motion abnormalities or systolic dysfunction. Because of excessive fatigue, the stress test was terminated at the end of step 3. The target heart rate and blood pressure were reached and there were no arrhythmia or ST-T wave changes. After further investigations and evaluations were performed, the patient was informed about the the possibility of a cardiac operation. The patient did not accept the treatment proposals and further investigation was not planned. The medical risks were explained to the patient and outpatient follow-up was scheduled with full oral medical treatment.

Coronary artery fistulas are rare anomalies that open into the heart chambers, large vessels and other structures by by-passing the myocardial capillary network[1]. The first case of coronary arteriovenous fistula was reported by Krause[4] in 1865. Coronary artery fistula is detected in 1.21%-5.60% of all patients undergoing coronary angiography[5]. A fistula from the coronary arteries to the pulmonary artery is observed in 0.1%-0.2% of coronary angiographies[6]. Atotal of 92% of coronary artery fistulas drain into the right heart chambers and 8% drains into the left heart chambers. The origins of the fistulae are vary, as follows: right coronary artery (50%-60%), left anterior descending artery (25%-42%), both coronary arteries (5%), circumflex artery (18%), diagonal artery (1.9%), marginal arteries (0.7%). Left main coronary artery fistula is extremely rare[2]. Although coronary artery fistulas are often congenital, they may occur after chest trauma, angiography and bypass surgery[7].

Coronary artery anomalies often affect hemodynamic parameters. Not all coronary-pulmonary artery fistulas are hemodynamically significant, However some may cause myocardial ischemia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary arterial hypertension, aneurysmal fistula rupture and sudden death[3].

Although two-dimensional echocardiography (transesophageal echocardiography complements two-dimensional echocardiography) is valuable in revealing the fistula, it is operator dependent and because it does not have a good acoustic window, determining the fistula location may be insufficient[8].

Until recently, using conventional coronary angiography to detect coronary anomalies was the preferred diagnostic method. However invasiveness, acquisition plane images, the lack of angiographic projection angle and concerns about the contrast load limit this method[9]. Multislice computed tomography (MSCT) can better reveal aneurysms, occlusion; as well as the direction of the fistula and its relationship with the cardiovascular structures along the fistula compared with coronary angiography[8]. MSCT imaging is the recommended technique for the diagnosis and follow up of coronary artery anomalies[10].

The treatment of asymptomatic patients without significant shunts is still a matter of debate[11]. The presence of ischemic symptoms or a positive stress test, aneurysmal dilatation with or without mural thrombus and overload of heart chambers due to excessive blood flow are the indications for fistula closure[12]. In the literature, similar early efficiency, mortality and morbidity rates are observed for both the surgical and transcatheter approaches[13].

In this case, although the fistula did not affect the hemodynamic parameters and the exercise test for ischemia was negative and because there was a large thrombosed aneurysm sac on the fistula line, transcatheter closure of the fistula was considered. The patient did not accept any attempt at surgical treatment, thus, further examination and treatment.could not be performed. The patient was discharged with with full oral medical treatment and recommendations. The patient has the risk of sudden death due to aneurysmal sac rupture and thromboembolic event due to aneurysm sac thrombus. Because of progression in the shunt system, a reduction in functional capacity and heart failure may develop. Coronary artery fistula is a possibility because of the degree of shunt or the patient’s symptoms; in addition, aneurysmal sacs and thrombus in the fistula line are possible[5,12].

The main symptom of the patient was exertional dyspnea.

The authors took into consideration the diseases , comorbidities and patient’s age which causes exertional dyspnea (e.g., coronary artery disease, pulmonary diseases, structural heart diseases, endocrine disoerders).

The authors made routine laboratory tests including BNP, pro-BNP, serum creatinine, urea, electrolytes, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, complete blood count.

Color doppler echocardiography and coronary angiography.

Transcatheter and surgical closure; Heart failure treatment; Nitrates, Acetylsalicylic acid, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor.

Coronary artery fistula: a sizable communication between a coronary artery and a chamber of the heart (coronary-cameral fistula) or any segment of the systemic or pulmonary circulation (coronary arteriovenous fistula).

The authors have learned how to diagnose a coronary fistula, manage its complications and treatment and searched the literature about its frequency and treatment modalities.

Interesting case report of a rare congenital coronary artery anomaly. This case represents the dilemmas of diagnosis, treatment and follow up of this rare cases.

P- Reviewer: Cademartiri F, Castillo R, Celik T, Peteiro J, Vijayvergiya R S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A

E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Vavuranakis M, Bush CA, Boudoulas H. Coronary artery fistulas in adults: incidence, angiographic characteristics, natural history. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1995;35:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chowdhury UK, Rizhvi A, Sheil A, Jagia P, Mittal CM, Govindappa RM, Malhotra P. Successful surgical correction of a patient with congenital coronary arteriovenous fistula between left main coronary artery and right superior cavo-atrial junction. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2009;50:73-78. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Levin DC, Fellows KE, Abrams HL. Hemodynamically significant primary anomalies of the coronary arteries. Angiographic aspects. Circulation. 1978;58:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Angelini P. Normal and anomalous coronary arteries: definitions and classification. Am Heart J. 1989;117:418-434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Rigatelli G, Docali G, Rossi P, Bovolon D, Rossi D, Bandello A, Lonardi G, Rigatelli G. Congenital coronary artery anomalies angiographic classification revisited. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2003;19:361-366. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ata Y, Turk T, Bicer M, Yalcin M, Ata F, Yavuz S. Coronary arteriovenous fistulas in the adults: natural history and management strategies. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;4:62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hsieh KS, Huang TC, Lee CL. Coronary artery fistulas in neonates, infants, and children: clinical findings and outcome. Pediatr Cardiol. 2002;23:415-419. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Jagia P, Goswami KC, Sharma S, Gulati GS. 16-MDCT in the evaluation of coronary cameral fistula. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W227-W228. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chan MS, Chan IY, Fung KH, Lee G, Tsui KL, Leung TC. Demonstration of complex coronary-pulmonary artery fistula by MDCT and correlation with coronary angiography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:S28-S32. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Utsunomiya D, Nishiharu T, Urata J, Ino M, Nakao K, Awai K, Yamashita Y. Coronary arterial malformation depicted at multi-slice CT angiography. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2006;22:547-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hong GJ, Lin CY, Lee CY, Loh SH, Yang HS, Liu KY, Tsai YT, Tsai CS. Congenital coronary artery fistulas: clinical considerations and surgical treatment. ANZ J Surg. 2004;74:350-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Angelini P. Questions on coronary fistulae and microfistulae. Tex Heart Inst J. 2005;32:53-55. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Armsby LR, Keane JF, Sherwood MC, Forbess JM, Perry SB, Lock JE. Management of coronary artery fistulae. Patient selection and results of transcatheter closure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 300] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |