Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.918

Revised: August 24, 2014

Accepted: September 16, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 165 Days and 12.1 Hours

Bezoars are accumulations of human or plant fiber located in the gastrointestinal tract of both humans and animals. Patients remain asymptomatic for several years, and the symptoms develop as these accumulations increase in size to the point of obstruction or perforation. We report the case of a 21-year-old patient at 10 d postpartum, who presented with acute abdomen associated with sepsis. Given the urgency of the clinical picture, at no point was the presence of a giant bezoar at gastric level suspected, specifically a trichobezoar. The emergency abdominal and pelvic ultrasound revealed only unspecific signs of perforated hollow viscus. Diagnosis was therefore made intraoperatively. A complete gastric trichobezoar was found with gastric perforation and secondary peritonitis. The peritoneal fluid culture revealed Candida glabrata.

Core tip: This case report describes the presentation of a gastric trichobezoar as an acute abdomen in puerperal woman with a detailed clinical description and images. The discussion provides an extensive analysis on the various types of treatments that exist today and their results, as well as evaluating its association with specific psychiatric diseases, and the finding of Candida infection in the patient evolution.

-

Citation: Morales HL, Catalán CH, Demetrio RA, Rivas ME, Parraguez NC, Alvarez MA. Gastric trichobezoar associated with perforated peptic ulcer and

Candida glabrata infection. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(12): 918-923 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i12/918.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.918

The trichobezoar is a rare medical condition composed of a mass of hair in the proximal gastrointestinal tract, which can cause obstruction, and almost exclusively affects young women[1,2]. Its prevalence ranges from 0.06% to 4% in the general population[3]. It is considered a result of trichotillomania, a psychiatric disorder linked to compulsively removing hair from the head and body in general[4]. When hair is ingested, it resists digestion and peristalsis, which is why it accumulates in the folds of the gastric mucosa. Mostly it remains confined to this level; but on some occasions it passes the pylorus, reaching the jejunum, ileum and even the colon. This condition was described for the first time by Vaughan et al[5] in 1968, and was called Rapunzel syndrome. The aim of this work is to report the clinical case of a patient with acute abdomen involving perforated hollow viscus associated with sepsis during the post-Cesarean period, who presented with a giant trichobezoar intraoperatively, and to review the clinical presentation, study through imaging, risk factors, complications and treatment.

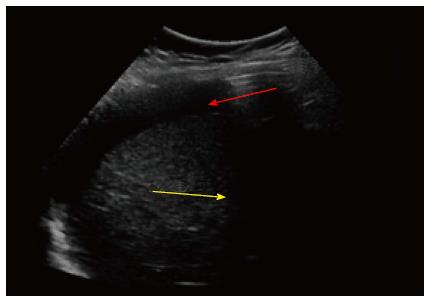

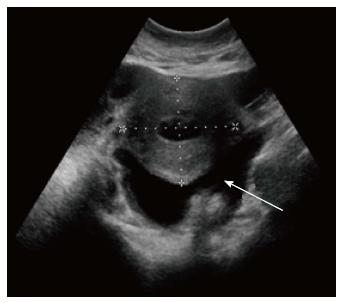

Patient, 21 years of age, female, with a history of insulin resistance with no current pharmacological treatment. She came to the emergency room of the Clínica Alemana Temuco, Chile ten days after an uneventful Cesarean section, referred from the hospital in Angol due to acute pain in her left side with 24 h of evolution, colicky in nature and with an intensity of 10/10 on the pain scale, without radiation, associated with sweating and involvement of her general state. In the initial evaluation, she was described as endomorph (BMI: 26), with altered vital signs in the range of systemic inflammatory response syndrome: blood pressure 124/80 mmHg; mean blood pressure 87 mmHg; heart rate 150 beats per minute in sinus rhythm; temperature 36 °C; respiratory rate 21 breaths per minute; oxygen saturation 98% with 3 L/min of oxygen via nasal prongs. On physical examination she was alert, focused and responsive (Glasgow Scale: 15 points), pale in skin and mucosa, vesicular murmur reduced in both lung fields, and abdomen distended with no sounds, yielding to the touch with diffuse tenderness with signs of peritoneal irritation. The laboratory examinations on admittance were as follows: hematocrit 34.7%; leukocyte count: 16100 K/uL; platelets: 984000 K/uL; erythrosedimentation rate: 41 mm/h; C-reactive protein: 502 mg/L; creatinine: 1.52 mg/dL; uremia: 64 mg/dL; prothrombin percentage/thromboplastin time: 55.7%/42.1 s; INR: 1.3; sodium: 134 mmol/L; potassium: 5.5 mmol/L; chlorine: 105 mmol/L. The abdominal-pelvic ultrasound taken in the emergency room revealed a moderate amount of free fluid and pneumoperitoneum; the uterus was enlarged due to purulent fluid at the bottom of the Pouch of Douglas (Figures 1 and 2). The patient was admitted to the ICU with diagnoses of: (1) Acute abdomen; (2) Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS); (3) Early postpartum 10th day Cesarean section; and (4) Acute renal dysfunction.

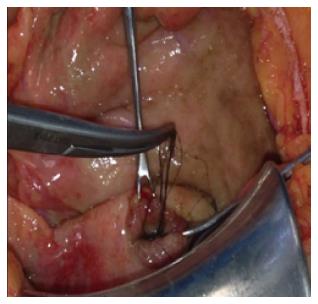

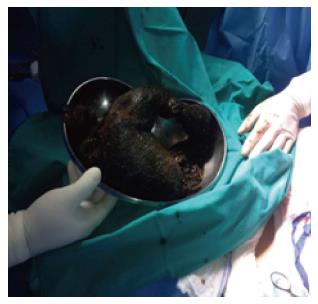

Support began with conservative therapy: zero regimen, oxygen therapy and resuscitation with fluids. Follow-up tests 3 h later: hematocrit: 23.5; leukocytes: 10500; platelets: 735000. The patient received antibiotic prophylaxis (2 g ceftriaxone and 500 mg metronidazole) and a transfusion of 2 UI of deep frozen fresh plasma. Through imaging, the patient was considered to be in post-Cesarean period with acute abdomen, abdominal sepsis and possible perforated hollow viscus. An exploratory laparotomy was performed, which found purulent fluid in 4 quadrants, a left subphrenic abscess, cecal appendix with the end phlegmonous and ulcerated, two perforated gastric ulcers, one in the anterior wall and another in the posterior wall, with a collection of gastric fluid in the omental bursa, and complete gastric trichobezoar involving the stomach and duodenum (weight: 1090 g) (Figure 3). The technique used was an anterior gastrotomy and bezoar extraction (Figures 4-6), closing the wound, including the ulcer, with a running stitch of 3-0 polydioxanone, single-layer suture and running stitch with 2-0 silk. Closing the ulcer in the posterior wall was done with 3-0 polydioxanone and an omental patch, fixing it with 3-0 silk.

The patient evolved favorably in the early postoperative phase, but at 3 d she began with a fever up to 38.9 °C, for which empirical antibiotic treatment was introduced. She remained hospitalized 25 d and in total and four days in intensive care unit. Peritoneal fluid culture was positive for Candida Glabrata; therefore, infectology assessed the case and decided to initiate anti-fungal drugs due to the presentation in the case of a hollow viscus rupture in conjunction with a bezoar. During hospitalization a psychiatric evaluation, during an interview of the patient and her mother, revealed that she had exhibited trichotillomania and trichophagia daily since the age of 12. The behavior decreased during pregnancy, and she was therefore diagnosed with moderate anxiety disorder with trichotillomania and inactive trichophagia. The methylene blue test was negative on the seventh postoperative day. Antibiotic therapy with ertapenem in addition to caspofungin was completed after two weeks. Evolution was good, with a good response, so discharge was given, completing oral anti-fungal treatment with voriconazole for three weeks.

A bezoar is defined as a mass of ingested foreign material accumulated in the digestive tract. It means “protection against poison” or antidote, given its use for curative purposes and even superstitions associated with good luck[6,7]. The first recorded case was in 1779, when Baudamant described the presentation in a woman[8]. Bezoars are classified into 5 groups according to the substance that comprises it: phytobezoar, pharmaco-bezoar, trichobezoar, lactobezoar and foreign body bezoar[9].

Bezoars are described as occurring in 1% of the population, associated mainly with gastric disorders such as hypomotility, hyposecretion with hypochlorhydria, and a history of resection[10]. In one retrospective study, 87 cases of intestinal bezoars were presented, in which diagnosis was made using the clinical history plus an endoscopy. The results included the presence of a prior surgery in 76 of the cases. In 3% of the cases, the most widely used technique was the bilateral truncal vagotomy with a pyloroplasty (75.8%). Other factors to consider would be an excess of plant fiber ingestion in 39.5%, and alterations in teething and chewing in 24%[11].

In our case it was more important specifically to investigate the presence of trichotillomania, a disorder listed in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, in the section on Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders[12]. Although its prevalence and comorbidity have not been clearly determined, different series of cases describe from 5% to 30% of patients with trichotillomania as having associated trichophagia[13-15], while 1% to 37.5% of these will develop a trichobezoar[13,15-17].

The clinical presentation generally occurs with symptoms and signs of acute abdomen and intestinal obstruction. This includes abdominal pain, nausea, bilious vomiting, hematemesis, anorexia, early satiety, weakness, weight loss and an abdominal mass[18-20]. Associated systemic complications include anemia, due either to nutritional deficit or gastrointestinal bleeding, and gastric ulcers have been documented in cases of gastric bezoars[21]. Imaging, such as ultrasound, can be useful in the detection of an abdominal mass, although computed tomography is more precise in assessing the characteristics of a bezoar and will allow the additional identification of bezoars in other places in the gastrointestinal tract. The diagnosis is established by endoscopy[2,18,22], and sometimes this can be effective as a treatment as we will analyze later.

In terms of surgical approach, this is where most of the debate lies with respect to management. Laparotomy, laparoscopy, endoscopic removal and even chemical dissolution in the case of phytobezoars have all been proposed. The choice is made on the basis of the size and composition of the bezoar[6,23].

The endoscopic removal of a trichobezoar has not been standardized, and a variety of techniques have been described in the literature, among which the following have been emphasized: fragmentation and removal with forceps, polypectomy snare, hydrolysis, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser, mechanical lithotripsy, electrohydraulic lithotripsy or extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy[9,24-27]. The first report of the successful endoscopic removal of a trichobezoar was for one that weighed 55 g[28]. An analysis of case reports where endoscopy was used as a first approach revealed a success rate of only 5%[29]. The difficulties of this technique are due to an unsuccessful fragmentation that might be explained by the size trichobezoars can reach, as well as by the density and hardness of the formed mass[30,31]. The repeated introduction of the endoscopy to achieve removal of all the fragments can cause esophagitis, pressure ulcers and even esophageal perforation[32]. Even in cases like ours of large trichobezoars, the attempt at fragmentation may allow the bezoars to migrate beyond they pylorus and cause an intestinal obstruction. The search for satellites in the intestine is not optimal with endoscopy, and their removal is impossible. Thus the role of endoscopy has advanced more towards diagnostic management than treatment. It allows us to differentiate, in the context of a gastric mass of an unknown nature, between a trichobezoar and foreign bodies that can be extracted or fragmented via endoscopy[33].

As far as surgical removal is concerned, it is important to differentiate between the classic and the laparoscopic approaches. The first report of a successful result of laparoscopy for a trichobezoar was published in 1998 regarding a 7-year-old girl[21]. To date the case reports endorsing this technique have been few, mainly in the pediatric population, limited mainly by the size and the presence of satellites in the intestine[29,30,32,34-37]. The combination of techniques has been used, implementing fragmentation laparoscopically and removal endoscopically[38]. The advantages of laparoscopy as it relates to a trichobezoar are a lower rate of postoperative complications, a reduced hospital stay, and a better cosmetic result. The disadvantages are a longer operating time, greater complexity in the review of the intestine in search of satellites, and the risk of contaminating the abdominal cavity with hair fragments[39].

The laparotomy has been successful in most cases: over 100 cases of successful results with this technique have been described[40]. Complications with this technique are described in 12% of the cases[40], and these include intestinal perforation during removal of the trichobezoar[41,42], infection of the surgical wound[43], pneumonia, and paralytic ileum[44].

Another interesting point to analyze in our case is the Candida Glabrata infection. One study reported on the cases presented for one year with a diagnosis of peritonitis due to a perforated peptic ulcer. There were 62 cases in all, of which 23 (37.09%) had peritoneal fluid cultures that tested positive for Candida, ten (16.12%) for isolated bacteria and the rest were negative. That analysis concluded there were no significant risk factors for developing the different species. In addition, they marked an important prognostic factor with an up to 21.7% likelihood of mortality for the case of Candida peritonitis, compared to the results for bacterial peritonitis and negative cultures, which were 0% and 3.4% respectively. The specific case of Candida Glabrata peritonitis was second in frequency (13.04%) in this series, surpassed by Candida Albicans peritonitis with 78.26%[45]. Other reports associate the gastric mycotic infection as a factor related to gastric perforation[46]. This point emphasizes the importance of taking a peritoneal fluid culture in patients with secondary peritonitis.

After the anti-fungal treatment, the patient in our report presented a good clinical evolution and was discharged with no associated morbidity.

Abdominal pain in a puerperal woman associated with systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Acute abdomen.

The principal differential diagnosis was the complications of previous cesarean section , as an uterine rupture or large bowel perforation.

Laboratory signs of systemic response.

Pneumoperitoneum and free fluid suggestive of pus.

Tricobezoar.

Anterior gastrotomy and bezoar extraction.

Psychiatric diseases in relation with tricobezoar.

Association with Candida Glabrata infection.

The authors need a high level of diagnostic suspicion, and use the anamnesis to find trichotillomania in antecedents to supply our diagnosis.

The case-report is interesting and so is the complication and super infection.

P- Reviewer: Coskun A, Zamir DL S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Diefenbach GJ, Reitman D, Williamson DA. Trichotillomania: a challenge to research and practice. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20:289-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Carr JR, Sholevar EH, Baron DA. Trichotillomania and trichobezoar: a clinical practice insight with report of illustrative case. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106:647-652. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Duke DC, Keeley ML, Geffken GR, Storch EA. Trichotillomania: A current review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:181-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association 2000; . |

| 5. | Vaughan ED, Sawyers JL, Scott HW. The Rapunzel syndrome. An unusual complication of intestinal bezoar. Surgery. 1968;63:339-343. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Andrus CH, Ponsky JL. Bezoars: classification, pathophysiology, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 1988;83:476-478. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Barbosa AL, Bromberg SH, Amorim FC, Gonçalves JE, Godoy AC. Obstrução intestinal por tricobezoar: Relato de caso e revisão da literatura. Rev Bras Coloproct. 1998;18:190-193 Available from: http://www.jcol.org.br/pdfs/18_3/07.pdf. |

| 8. | Koulas SG, Zikos N, Charalampous C, Christodoulou K, Sakkas L, Katsamakis N. Management of gastrointestinal bezoars: an analysis of 23 cases. Int Surg. 2008;93:95-98. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Hall JD, Shami VM. Rapunzel’s syndrome: gastric bezoars and endoscopic management. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006;16:111-119. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hewitt AN, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Laufer I. Gastric bezoars: reassessment of clinical and radiographic findings in 19 patients. Br J Radiol. 2009;82:901-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Escamilla C, Robles-Campos R, Parrilla-Paricio P, Lujan-Mompean J, Liron-Ruiz R, Torralba-Martinez JA. Intestinal obstruction and bezoars. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:285-288. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Stein DJ, Grant JE, Franklin ME, Keuthen N, Lochner C, Singer HS, Woods DW. Trichotillomania (hair pulling disorder), skin picking disorder, and stereotypic movement disorder: toward DSM-V. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:611-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bouwer C, Stein DJ. Trichobezoars in trichotillomania: case report and literature overview. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:658-660. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Frey AS, McKee M, King RA, Martin A. Hair apparent: Rapunzel syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:242-248. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Salaam K, Carr J, Grewal H, Sholevar E, Baron D. Untreated trichotillomania and trichophagia: surgical emergency in a teenage girl. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:362-366. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Christenson GA, Mackenzie TB, Mitchell JE. Characteristics of 60 adult chronic hair pullers. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:365-370. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Christenson GA, Crow SJ. The characterization and treatment of trichotillomania. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57 Suppl 8:42-47; discussion 48-49. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Sehgal VN, Srivastava G. Trichotillomania +/- trichobezoar: revisited. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:911-915. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Pérez E, Sántana JR, García G, Mesa J, Hernández JR, Betancort N, Núñez V. Gastric perforation due to trichobezoar in an adult (Rapunzel syndrome). Cir Esp. 2005;78:268-270. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Deslypere JP, Praet M, Verdonk G. An unusual case of the trichobezoar: the Rapunzel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1982;77:467-470. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Nirasawa Y, Mori T, Ito Y, Tanaka H, Seki N, Atomi Y. Laparoscopic removal of a large gastric trichobezoar. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:663-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coulter R, Antony MT, Bhuta P, Memon MA. Large gastric trichobezoar in a normal healthy woman: case report and review of pertinent literature. South Med J. 2005;98:1042-1044. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lee J. Bezoars and foreign bodies of the stomach. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:605-619. [PubMed] |

| 24. | O’Sullivan MJ, McGreal G, Walsh JG, Redmond HP. Trichobezoar. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:68-70. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Muguruma N, Okamura S, Okahisa T, Yasuda M, Hayashi S, Shibata H, Ito S. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy treatment for persimmon bezoars. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S60. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Wang YG, Seitz U, Li ZL, Soehendra N, Qiao XA. Endoscopic management of huge bezoars. Endoscopy. 1998;30:371-374. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Kuo JY, Mo LR, Tsai CC, Chou CY, Lin RC, Chang KK. Nonoperative treatment of gastric bezoars using electrohydraulic lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 1999;31:386-388. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Saeed ZA, Ramirez FC, Hepps KS, Dixon WB. A method for the endoscopic retrieval of trichobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:698-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pogorelić Z, Jurić I, Zitko V, Britvić-Pavlov S, Biocić M. Unusual cause of palpable mass in upper abdomen--giant gastric trichobezoar: report of a case. Acta Chir Belg. 2012;112:160-163. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Tudor EC, Clark MC. Laparoscopic-assisted removal of gastric trichobezoar; a novel technique to reduce operative complications and time. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48:e13-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Tiago S, Nuno M, João A, Carla V, Gonçalo M, Joana N. Trichophagia and trichobezoar: case report. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2012;8:43-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kanetaka K, Azuma T, Ito S, Matsuo S, Yamaguchi S, Shirono K, Kanematsu T. Two-channel method for retrieval of gastric trichobezoar: report of a case. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:e7. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Gaia E, Gallo M, Caronna S, Angeli A. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastric bezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:113-114. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Cintolo J, Telem DA, Divino CM, Chin EH, Midulla P. Laparoscopic removal of a large gastric trichobezoar in a 4-year-old girl. JSLS. 2009;13:608-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Meyer-Rochow GY, Grunewald B. Laparoscopic removal of a gastric trichobezoar in a pregnant woman. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2007;17:129-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hernández-Peredo-Rezk G, Escárcega-Fujigaki P, Campillo-Ojeda ZV, Sánchez-Martínez ME, Rodríguez-Santibáñez MA, Angel-Aguilar AD, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez C. Trichobezoar can be treated laparoscopically. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:111-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Levy RM, Komanduri S. Images in clinical medicine. Trichobezoar. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Yau KK, Siu WT, Law BK, Cheung HY, Ha JP, Li MK. Laparoscopic approach compared with conventional open approach for bezoar-induced small-bowel obstruction. Arch Surg. 2005;140:972-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Memon SA, Mandhan P, Qureshi JN, Shairani AJ. Recurrent Rapunzel syndrome - a case report. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:CS92-CS94. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Al-Janabi IS, Al-Sharbaty MA, Al-Sharbati MM, Al-Sharifi LA, Ouhtit A. Unusual trichobezoar of the stomach and the intestine: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Perera BJ, Romanie Rodrigo BK, de Silva TU, Ragunathan IR. A case of trichobezoar. Ceylon Med J. 2005;50:168-169. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Larsson LT, Nivenius K, Wettrell G. Trichobezoar in a child with concomitant coeliac disease: a case report. Acta Paediatr. 2004;93:278-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zent RM, Cothren CC, Moore EE. Gastric trichobezoar and Rapunzel syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Varma A, Sudhindra BK. Trichobezoar with small bowel obstruction. Indian J Pediatr. 1998;65:761-763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lee SC, Fung CP, Chen HY, Li CT, Jwo SC, Hung YB, See LC, Liao HC, Loke SS, Wang FL. Candida peritonitis due to peptic ulcer perforation: incidence rate, risk factors, prognosis and susceptibility to fluconazole and amphotericin B. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;44:23-27. [PubMed] |

| 46. | Gupta N. A rare cause of gastric perforation-Candida infection: a case report and review of the literature. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1564-1565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |