Published online Dec 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.840

Revised: October 7, 2014

Accepted: October 23, 2014

Published online: December 16, 2014

Processing time: 167 Days and 6.8 Hours

Necrosis of pancreatic parenchyma or extrapancreatic tissues is present in 10%-20% of patients with acute pancreatitis, defining the necrotizing presentation frequently associated with high morbidity and mortality rates. During the initial phase of acute necrotizing pancreatitis the most important pillars of medical treatment are fluid resuscitation, early enteral nutrition, endoscopic retrograde colangiopancreatography if associated cholangitis and intensive care unit support. When infection of pancreatic or extrapancreatic necrosis occurs, surgical approach constitutes the most accepted therapeutic option. In this context, we have recently assited to changes in time for surgery (delaying the indication if possible to around 4 wk to deal with “walled-off” necrosis) and type of access for necrosectomy: from a classical open approach (with closure over large-bore drains for continued postoperative lavage or semiopen techniques with scheduled relaparotomies), trends have changed to a “step-up” philosophy with initial percutaneous drainage and posterior minimally invasive or endoscopic access to the retroperitoneal cavity for necrosectomy if no improvement has been previously achieved. These approaches are progressively gaining popularity and morbidity and mortality rates have decreased significantly. Therefore, a staged, multidisciplinary, step-up approach with minimally invasive or endoscopic access for necrosectomy is widely accepted nowadays for management of pancreatic necrosis.

Core tip: We have recently assisted to a significant change in surgical approach to acute pancreatitis. Infection continues as the most important pillar where surgical indication is established. Nevertheless, from an early consideration for surgery frequently performed by classical open approach, today we have moved to delay the indication and the procedure as much as possible with step-up philosophies trying to deal with “walled-off” necrosis and considering minimally invasive access like video-assisted retroperitoneal or endoscopic. In this paper, most recent therapeutic trends for acute necrotizing pancreatitis are reviewed.

- Citation: Aranda-Narváez JM, González-Sánchez AJ, Montiel-Casado MC, Titos-García A, Santoyo-Santoyo J. Acute necrotizing pancreatitis: Surgical indications and technical procedures. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(12): 840-845

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i12/840.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i12.840

Gallstones and alcohol are still the most frequent causes of Acute Pancreatitis (AP), a disease with an increasing incidence in recent decades. Diagnosis is based on the presence of two of the following criteria: (1) characteristic upper abdominal pain radiating in a belt-shaped fashion; (2) amylase or lipase values three times above normal levels; and (3) demonstrative radiologic imaging.

Due to the confusion created by certain terminology derived from the Atlanta classification of AP, a recent revision of the terminology has been developed from an International Consensus, which currently constitutes the reference of the conceptual definition of AP (Table 1). AP is classified into its two forms of presentation (Interstitial Edematous Pancreatitis and Necrotizing Pancreatitis), and according to the severity of the clinical course (mild, moderate and severe). Most AP episodes occur as an interstitial edematous form (80%-90%), usually associated to a mild clinical course, while more clinical severity is frequently associated to the characteristic that defines acute necrotizing pancreatitis (ANP): necrosis, pancreatic or peripancreatic, or a mix of both[1,2].

| Types | |

| Interstitial edematous | Inflammation of pancreatic parenchyma and peripancreatic tissue, without necrosis |

| Necrotizing | Inflammation with pancreatic parenchymal and/or peripancreatic necrosis |

| Grades of severity | |

| Mild | No organ failureLack of local or systemic complications |

| Moderate | Transient organ failure (< 48 h) and/orLocal or systemic complications without persistent organ failure |

| Severe | Persistent single or multiple organ failure(> 48 h) |

Local complications associated to the edematous form are defined depending on whether they have or not a well-defined wall and on the time of their arising. Acute fluid collections arise within the first 4 wk of the clinical course and lack a well-defined wall, while pseudocysts are circumscribed fluid collections that occur more than 4 wk after the onset of AP and have a well-defined wall. These complications are out of the scope of the current revision, since their surgical management is not necessary or it is included among elective treatments. On the other part, necrotizing forms may be associated to acute necrotic collections (intra- or extra-pancreatic solid-liquid heterogeneous collection with no defined wall, diagnosed during the first 4 wk of the clinical course) or walled-off necrosis (with similar characteristics but with well-defined wall and with a later diagnosis, above 4 wk). This later concept gathers all previous terms (necroma, pancreatic sequestrum, subacute pancreatic necrosis or pancreatic pseudocyst with necrosis) into a common terminology. Other local complications associated to AP include splenic/portal thrombosis, colon necrosis, retroperitoneal hemorrhage or delayed gastric emptying[1,2].

Physiopathologically, two events may determine the severity of the clinical course. The first of them is the associated Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS), which involves a complex inflammatory cascade, which can finally cause the characteristic single- or multiorgan failure. Respiratory, renal and cardiovascular are the most frequent organic failures associated to AP. The second event is infection of necrosis, which is usually associated to phenomena of bacteria translocation. Both events constitute critical factors determining the clinical course of AP and they establish even the current indications for surgery in AP; thus, they will be expounded in detail later on[3].

During the first week after the onset of AP, treatment is medical. Frequently, surgeons on duty are called to evaluate patients with AP without response to medical treatment during the initial phase of the disease. For decision making in this context it must be assumed that the reason for lack of response in these patients is based more in the presence and progression of SIRS than in the potential necrosis or pancreatic infection. Thus, surgery is not indicated during this phase, unless a suspicion of ischemia or perforation as a secondary complication arises. Surgery during this first phase aggravates the multiorgan failure and results in a greater rate of complications, such as intestinal hemorrhage or fistula[4].

In this phase, fluid resuscitation is essential during the first 12-24 h, having to be reduced later on trying to avoid intra abdominal hypertension (IAH), frequently associated to AP. A recent review could not find any difference between fluid resuscitation with colloid or crystalloid solutions[5]. Prophylactic antibiotics are not indicated, since they have not shown a clear benefit in previous studies and metaanalysis, and thus, they should not be used until an associated infection is clearly demonstrated[4]. Early (on the first 72 h) Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography has not shown benefits when performed systematically in AP in the absence of cholangitis, although an ongoing clinical trial is analyzing this approach again (APEC trial; ISRCTN97372133). However, in presence of bile duct obstruction it is clearly indicated[6].

During this first week, surgeons are occasionally requested to evaluate patients with AP and IAH, present in 61% of episodes of AP. IAH is the precursor of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome (ACS) and, thus, of multiorgan failure. Although the beneficial effect of decompression to alleviate ACS is clear in other situations, in AP the ACS seems to be closer related to massive resuscitation, ascites or retroperitoneal fluid accumulation and, thus, treatment strategies with decompressive laparotomy have not shown a clear benefit in terms of morbidity and mortality. Currently, management strategies for AP-associated ACS are directed towards medical support (negative fluid balance, enteral decompression, pharmacological increase of the abdominal wall compliance) and even towards percutaneous drainage of fluid collections (with a related ongoing clinical trial, the DECOMPRESS Study; ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00793715). In case abdominal surgical decompression had to be performed during this first phase, in absence of infected necrosis, the retroperitoneum should not be opened[4].

This is the moment to consider the necessity and indication for surgery of the pancreatic necrosis, on which we will expound extensively. Other local complications may occur at this phase but they are much less frequent and will be mentioned at the end of the chapter.

Most common indications for surgery of pancreatic necrosis are the following: (1) infection. It is a rare event during the first week of clinical course. The diagnosis is based on the association of sepsis signs with compatible radiologic imaging (extraluminal air in intra- or extra-pancreatic necrotic areas in CT imaging) and on the occasional support of vascular radiologists with percutaneous fine-needle aspiration for Gram staining and culture. There is universal consensus that a need for therapeutic action exists; (2) single- or multiorgan failure. Organ failure is classified as transient or persistent based on whether it lasts less or more than 48 h, respectively. The most recommended system for its definition (even above the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment -SOFA-) is the Marshall score[7] (Table 2), which is easy and repeatable along the clinical course of AP. It evaluates the three most commonly SIRS-affected systems (respiratory, renal and cardiovascular) and defines organ failure as a score of 2 or more.

| Organ system | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Respiratory (PaO2/FiO2) | > 400 | 300-400 | 200-300 | 100-200 | < 100 |

| Renal (Creatinine, mg/dL) | < 1.4 | 1.4-1.8 | 1.8-3.6 | 3.6-5 | > 5 |

| Cardiovascular (mmHg) | > 90 | < 90, fluid responsive | < 90, not fluid responsive | < 90, pH < 7.3 | < 90, pH < 7.2 |

A persistent single- or multiorgan failure refractory to support treatment may constitute an indication for surgery. Numerous studies have shown that in this context, oppositely to what happens when infection constitutes the indication for surgery, necrosectomy does not provide a significant benefit regarding mortality, and thus, it must be considered as the last resource in a patient in whom maximum medical support does not result in clear improvement. We can assert the same statements when surgical indication is established on a patient with ANP with no clinical improvement after 4-6 wk of intensive medical treatment.

We must consider that the indication for surgery in the context of AP must derive more from the need to control complications than from the inflammatory process itself. Regarding this, every necrotic and infected tissue must be removed, and pus drained. Material viscosity, as well as the number and localizations of potentially drainable regions constitute determining factors for the selection of the best therapeutic approach. Morbidity associated to pancreatic debridement includes pancreatic fistula (50%), endo- and exocrine pancreatic failure (20%), intestinal fistula (10%) and the common prolonged hospitalization and delay in the incorporation to daily life activities[3,4].

It is important to underline some important concepts before describing the different surgical options: (1) debridement is preferred over resection for two reasons: first, as an attempt to conserve the maximum quantity of functional pancreatic tissue, and second, due to the frequent technical impossibility of pancreatic resection and its associated morbidity in the context of AP[3,4]; (2) unless evident infection of necrosis exists, survival improves as the surgical indication gets delayed. The best results are obtained when the indication may be delayed up to one month after the onset of the clinical symptoms. A better demarcation of necrosis (conversion to “walled-off” pancreatic necrosis) involves less bleeding and less removal of viable tissues[3,4]; and (3) Two different philosophies define the timing of the surgical approach for a patient with AP. “Step-down” consists on the classical immediate surgical approach when there is an established indication, and, later on, a more conservative treatment for the residual disease. However, there is a trend in the most recent medical literature towards a “step-up” type of concept, where more conservative procedures (percutaneous, laparoscopic or endoscopic procedures) constitute the initial treatment of patients with ANP and a final technique is performed later on if necessary, based on poor clinical evolution[8].

Open necrosectomy: Open necrosectomy (ON) was considered as the gold standard treatment for decades, and it was usually associated to a therapeutic “step-down” type of approach. Classical ON consists on debridement of the necrotic pancreatic tissue through a midline or subcostal bilateral incision and the access to the pancreatic area through the lesser sac, the gastrocolic omentum or by a transmesenteric access through the transverse mesocolon, depending on necrosis extension and localization. Once the necrosectomy has been performed, the options are: (1) usual closure over drains and relaparotomy depending on clinical course; (2) scheduled laparotomies, usually every 48 h, until debridement has been completed. Open abdomen techniques are recommended if this approach is selected, but scheduled laparotomies closing the abdomen after each revision have also been reported; and (3) closed technique with abdominal closure over lavage system with large-bore drains in the pancreatic area.

The last one constitutes the most recommended option based on a mortality < 10%, significantly inferior to those associated to the rest of the techniques. Nevertheless, an effective comparison between the different methods is difficult because of the heterogeneity of patients and surgeons[3,4,9].

Percutaneous drainage: Several series of patients have reported that management of infected pancreatic necrosis with percutaneous drainage (PD) obtains a high success rate and mortality similar to that of ON treatment. In a systematic review[10], the success rate of PD (defined as survival with no need for additional surgical necrosectomy) was 55%, mortality 17% and morbidity 21%, showing pancreaticocutaneous and pancreaticoenteric fistulas as the most frequent complications associated to the procedure. Although PD constitutes a tempting and efficient therapeutic alternative as a minimally aggressive approach, the truth is that frequently success depends on the availability of large caliber catheters and often repeated procedures are needed. For selected patients, like those with AP and easily accessible single infected necrosis, or as a transient step to surgery in unstable patients, this therapeutic option must be considered. However, PD is not accepted as a useful tool when an extensive necrosectomy is needed[3,4,9].

Endoscopic approach: A promising approach for pancreatic necrosis is the transgastric or transduodenal endoscopic approach (EA) under direct vision or with ultrasound support. Very diverse types of instruments are later used to maintain opened the communication between the digestive lumen and the necrosis and to perform the necrosectomy, and frequently repeated procedures are needed. Several series have reported promising results with EA, some as important as the German multicenter GEPARD Study[11] with 93 patients, 81% of clinical success and only 7.5% mortality. The results of EA for necrotizing AP have been recently summarized in a systematic review[12], which reports a success rate of 75% on 260 patients; however, it must be pointed out that data derive from non-randomized studies on selected patients in reference centers.

Laparoscopic approach: Laparoscopic approach (LA) for ANP may result particularly attractive because of its potential of obtaining all the advantages of a minimally invasive approach while maintaining access to the whole abdominal cavity (perirenal and retroduodenal spaces and mesenteric root, as well as both paracolic gutters) and the technical possibility of indicating additional techniques (cholecystectomy or jejunostomy). However, the extension of LA in ANP among professionals is still scarce, since its advantages are overpassed by its limitations: infection dissemination, need for pneumoperitoneum in unstable patients, or the possibility of iatrogenic intestinal perforations. Published series of patients have a scarce number of cases and it is still soon to recommend this approach[3,4].

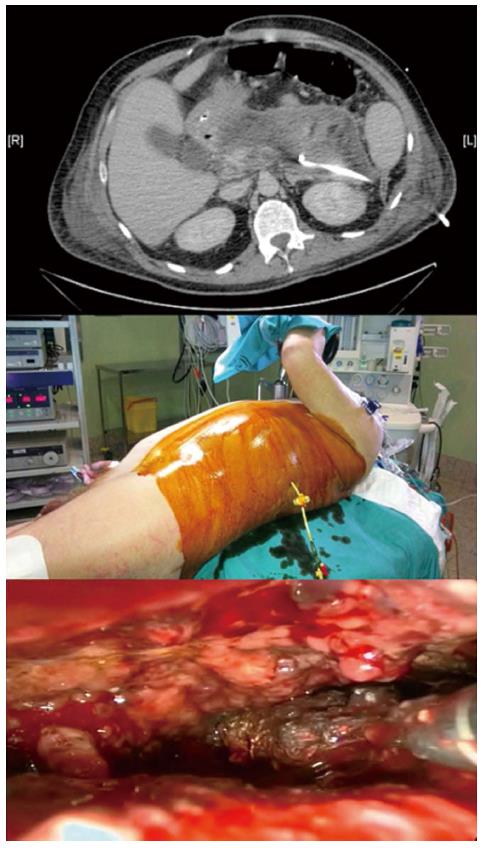

Retroperitoneal approach: It constitutes the maximum example of Minimally Invasive Necrosectomy. Retroperitoneal approach (RA) of the necrosis is performed through small incisions and the use of endoscopic material, guided by a percutaneous drainage previously and strategically indicated, placed laterally, avoiding access to the abdominal cavity and providing all the advantages of the minimally invasive approach. Diverse methods for its performance have been described but the most widely accepted are Minimal Access Retroperitoneal Pancreatic Necrosectomy (MARPN) and Video-Assisted Retroperitoneal Debridement (VARD) (Figure 1). This last one consists in the introduction of a laparoscopic camera, through a 5 cm incision, and after the first liquid and solid debris have been removed a vigorous debridement of the necrotic cavity may be performed with the maintenance of a low-pressure pneumoperitoneum. The number of repeated necrosectomies needed later on is significantly lower with VARD than with MARPN.

In a systematic review, incidence of multiorgan failure, incisional hernia and endo- and exocrine failure was significantly lower with RA than with ON, although mortality was similar and no differences were observed regarding local complications, such as intraabdominal bleeding or pancreatic fistula[13].

Combined approaches with “step-up” philosophy: Probably, management of pancreatic necrosis in an immediate future will not be based only in one of the methods already mentioned. A combination of them with a decision making based on characteristics of the patient, necrosis grade, extension and localization will be the key for defining the best therapeutic option in ANP. The most illustrative of these approaches is the Dutch PANTER[14] (PAncreatitis, Necrosectomy vs sTEp up appRoach) study, a randomized, multicenter, clinical trial in which 88 patients with necrotizing AP who met inclusion criteria, and in whom the need to perform an invasive procedure was established (delayed whenever as possible up to 4 wk from the onset of the clinical symptoms) were divided into two groups: 45 with ON and 43 with “step-up” type minimally invasive approach. Such an approach consisted in placing a percutaneous drainage as the first step (40 retroperitoneal, 1 abdominal and 2 endoscopic), assessing the placement of a second drainage or the performance of RA in the absence of improvement after 72 h, based on clinical and radiologic findings. The morbi-mortality rate of the “step-up” type of approach was significantly lower than that of the ON group (40% vs 69%, P < 0.006), and so was the multiorganic failure (12% vs 40%, P < 0.002). In addition, it was defined that more than 30% of patients in the “step-up” group did not need necrosectomy after the percutaneous or endoscopic drainage.

On the same line of therapeutic combination, the ongoing TENSION study (ISRCTN 09186711) randomizes 98 patients with ANP to receive step-up type endoscopic approach vs surgical approach.

Disruptions of the main pancreatic duct may derive in internal or external fistulas, pancreatic ascites or pleural effusion. Treatment constitutes an important challenge and, depending on location and clinical manifestation, it can require from PD as the only procedure up to pancreatic resection or Roux-en-Y derivation for what is called the Disconnected Pancreatic Duct Syndrome, although a CPRE approach and transpapillar drainage is usually sufficient[3].

Vascular complications occur in 2.4%-10% of patients with AP, and they derive from bleeding into the peritoneal cavity or into the gastrointestinal tract from pseudoaneurysms of vessels close to the inflammatory process, such as the gastroduodenal or pancreaticoduodenal arteries. Nowadays, embolization is the therapeutic method of choice[3,4].

Colonic complications associated with pancreatitis are infrequent (1% of cases). From reactive ileus to most severe forms with obstruction, necrosis or perforation are associated to poor prognosis and mortality increase. For the majority of cases, resection with proximal ostomy and mucous fistula constitutes the treatment for these complications.

Maybe out of the emergency context but of necessary mention, it must be underlined that there is an indication for cholecystectomy in the first admission after the first mild gallstones pancreatitis. A systematic review reported up to 18% readmissions in patients with mild AP if an early cholecystectomy is not indicated and performed[15]. In severe AP, however, cholecystectomy should be deferred until complete resolution of inflammation[16].

In recent years we have witnessed a change in the management of patients with ANP: from a prematurely indicated surgery, performed open, we are moving to less aggressive procedures, indicated later and with “step-up” strategies, performing first PD, preferably retroperitoneal, and continuing with surgical (considering new access routes) or endoscopic necrosectomy in case of absence of improvement. These concepts require a multidisciplinary approach to ANP with implication of surgeons, gastroenterologists, radiologists, and intensive care unit doctors, and the need for contemplating the referral of patients to reference centers when the needed logistic is not available. Trauma and Emergency Surgery Units in the Departments of General and Digestive Surgery constitute, thus, the ideal setting for the early diagnosis, indication, intervention and follow-up of these patients.

P- Reviewer: Bradley EL, Cochior D S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

| 1. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4344] [Article Influence: 362.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 2. | Sarr MG, Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. The new revised classification of acute pancreatitis 2012. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:549-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Martin RF, Hein AR. Operative management of acute pancreatitis. Surg Clin North Am. 2013;93:595-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | da Costa DW, Boerma D, van Santvoort HC, Horvath KD, Werner J, Carter CR, Bollen TL, Gooszen HG, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ. Staged multidisciplinary step-up management for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2014;101:e65-e79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Haydock MD, Mittal A, Wilms HR, Phillips A, Petrov MS, Windsor JA. Fluid therapy in acute pancreatitis: anybody’s guess. Ann Surg. 2013;257:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tse F, Yuan Y. Early routine endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography strategy versus early conservative management strategy in acute gallstone pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD009779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Marshall JC, Cook DJ, Christou NV, Bernard GR, Sprung CL, Sibbald WJ. Multiple organ dysfunction score: a reliable descriptor of a complex clinical outcome. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1638-1652. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schneider L, Büchler MW, Werner J. Acute pancreatitis with an emphasis on infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2010;24:921-941, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Baal MC, van Santvoort HC, Bollen TL, Bakker OJ, Besselink MG, Gooszen HG. Systematic review of percutaneous catheter drainage as primary treatment for necrotizing pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 2011;98:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Seifert H, Biermer M, Schmitt W, Jürgensen C, Will U, Gerlach R, Kreitmair C, Meining A, Wehrmann T, Rösch T. Transluminal endoscopic necrosectomy after acute pancreatitis: a multicentre study with long-term follow-up (the GEPARD Study). Gut. 2009;58:1260-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 333] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 19.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Haghshenasskashani A, Laurence JM, Kwan V, Johnston E, Hollands MJ, Richardson AJ, Pleass HC, Lam VW. Endoscopic necrosectomy of pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3724-3730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cirocchi R, Trastulli S, Desiderio J, Boselli C, Parisi A, Noya G, Falconi M. Minimally invasive necrosectomy versus conventional surgery in the treatment of infected pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and a meta-analysis of comparative studies. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:8-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | van Santvoort HC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, Hofker HS, Boermeester MA, Dejong CH, van Goor H, Schaapherder AF, van Eijck CH, Bollen TL. A step-up approach or open necrosectomy for necrotizing pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1491-1502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1038] [Cited by in RCA: 1037] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Baal MC, Besselink MG, Bakker OJ, van Santvoort HC, Schaapherder AF, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Gooszen HG, van Ramshorst B, Boerma D. Timing of cholecystectomy after mild biliary pancreatitis: a systematic review. Ann Surg. 2012;255:860-866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1041] [Article Influence: 86.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |