Published online Nov 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.728

Revised: July 7, 2014

Accepted: August 27, 2014

Published online: November 16, 2014

Processing time: 188 Days and 8.3 Hours

Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rare cause of intestinal obstruction with unknown etiology. Diagnosis of this syndrome, which can be summarized as the small intestine being surrounded by a fibrous capsule not containing the mesothelium, is difficult in the preoperative period. A 47-year-old male patient was referred to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for two days. The abdominal computed tomography examination detected dilated small intestinal loops containing air-fluid levels clustered in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and surrounded by a thick, saclike, contrast-enhanced membrane. During exploratory surgery, a capsular structure was identified in the upper left quadrant with a regular surface that was solid-fibrous in nature. Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rarely seen condition, for which the preoperative diagnosis is difficult. The combination of physical examination and radiological signs, and the knowledge of “recurrent characteristics of the complaints” that can be learned by a careful history, may be helpful in diagnosis.

Core tip: Abdominal “cocoon” is an extremely rare cause of small bowel obstruction. It should be thought of as a rare cause of small bowel obstruction. Its diagnosis is rarely made preoperatively. It has been reported mainly in young adolescent women. But in this adult patient, the small bowel is encased in a fibrous sac called an abdominal cocoon. The clinical manifestations of abdominal “cocoon” are non-specific. The combination of physical examination and radiological signs, and the knowledge of “recurrent characteristics of the complaints” which can be learned by a careful history, may be helpful in diagnosis. Surgery remains the main stay of treatment with satisfactory outcome.

- Citation: Uzunoglu Y, Altintoprak F, Yalkin O, Gunduz Y, Cakmak G, Ozkan OV, Celebi F. Rare etiology of mechanical intestinal obstruction: Abdominal cocoon syndrome. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(11): 728-731

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i11/728.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.728

Abdominal cocoon syndrome, which was first defined in 1978[1], is relatively rare, with descriptions in the literature limited to case reports. In this syndrome, a portion or all of the small intestine is surrounded with a fibrocollagenous membrane not containing the mesothelium. As it is rarely seen, and its clinical findings nonspecific, it is generally diagnosed during surgery[2]. However, it can be characterized by the membrane surrounding the small intestine with contrast-enhanced abdominal computerized tomography (CT) during the preoperative period. Surgical treatment that releases the small intestine by cutting away the adhesions after excision of the membrane is the basic intervention in these cases. This article presents a case with abdominal cocoon syndrome diagnosed, following recurrent complaints, with abdominal CT during the preoperative period and surgically treated.

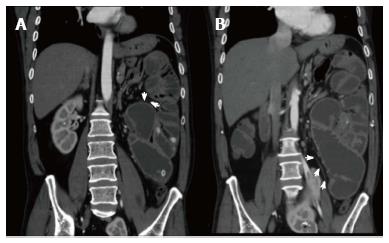

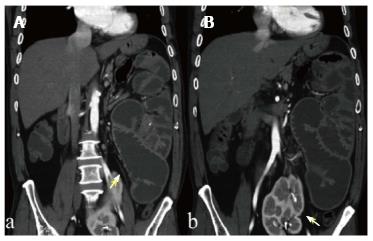

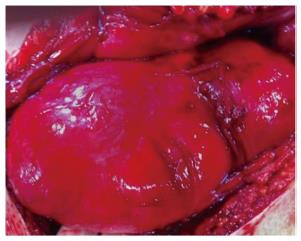

A 47-year-old male patient was referred to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for two days. The detailed medical history of the patient, who did not have a known chronic systemic disease or a previous history of any abdominal procedures, revealed similar complaints dating back several years that recurred at certain time intervals and had been treated. Upon physical examination, there was asymmetrical distension and general tenderness, especially prominent in upper regions of the abdomen, with heightened intestinal sounds. The laboratory examinations were normal, except for leukocytosis (14.300 mm3). Multiple air-fluid levels were detected on abdominal radiography, which was more prominent in the left upper quadrant (Figure 1). The abdominal CT examination detected dilated small intestinal loops containing air-fluid levels clustered in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and surrounded by a thick, saclike, contrast-enhanced membrane. The left kidney was also located ectopically at the midline in the abdomen at the level of the pelvis (Figures 2 and 3). During exploratory surgery, widespread adhesions with the peritoneum and small intestine could not be seen. Upon further exploration, a capsular structure was identified in the upper left quadrant with a regular surface that was solid-fibrous in nature. Only 20 cm of the jejunal and ileal segments in the proximal and distal portions of the small intestine were intra-abdominally localized. The remaining small intestinal segments were inside this structure and the greater omentum was hypoplastic (Figure 4). When the capsule was opened, the small intestinal segments inside the capsule were dilated due to obstruction but otherwise normal in structure. The obstruction was caused by fibrous bands of irregular thickness inside the capsule. The operation was completed after total excision of the capsule and removal of the adhesions. The patient manifested clinical signs of ileus on postoperative day 3 due to the adhesions. He was medically treated with nasogastric decompression and parenteral nutrition and discharged on postoperative day 12 without any problems. Upon histopathological examination, a nonspecific inflammatory reaction in conjunction with fibrous connective tissue proliferation was found. On the third month of his follow-up, the patient did not report any problems.

Abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rare cause of acute or subacute intestinal obstruction, and its’ classified as primary (idiopathic) and secondary. Although the etiology is not precisely known, conditions that result in chronic asymptomatic peritonitis (such as: the use of practalol, peritoneal dialysis, endometriosis, and abdominal tuberculosis) are risk factors. Moreover, accompanied by some diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, familial Mediterranean fever, infections of the Fallopian tubes, retrograde menstruation) have also been reported[3-6] . In a two-case series reported by Yeniay et al[7], the greater omentum was absent, suggesting that genetic factors may also play a role in the etiology. Our case reports the role of genetic factors since our patient developed chronic peritonitis without having any of the known risk factors, the greater omentum was hypoplastic, and there was a locational abnormality in the left kidney.

The clinical presentation of abdominal cocoon syndrome is generally acute or subacute intestinal obstruction. There is an increase in intestinal sounds and abdominal distension on physical examination. However, abdominal distension may be asymmetrical, as the small intestine is surrounded by a membrane and not mobile[8]. Common complaints during patient history include the recurrence of nonspecific symptoms such as nausea and vomiting that spontaneously recover or respond to medical therapy. Chronic constipation, anorexia, weight loss, and intra-abdominal masses rarely present in these patients[9]. In the current case, there were signs of intestinal obstruction associated with asymmetrical distension during the physical examination of the abdomen.

As it is rarely seen and the clinical symptoms are nonspecific, diagnosis in the preoperative period is difficult. Clusters of intestinal loops and a surrounding membrane in contrast-enhanced abdominal CT, especially multislice CT, are diagnostic[10]. An abdominal CT that is performed during the preoperative period provides both diagnosis and differential diagnosis, and determines the associated congenital changes, such as the midline location of the left kidney in our case. This prevents undesirable complications during surgery. However, in spite of all opportunities, preoperative diagnosis is difficult and requires advanced radiological experience. In a retrospective study of twenty-four cases, it was reported that only 16% of the cases could be preoperatively diagnosed[11].

There is a consensus that surgical treatment is ideal in these patients. The recommended procedure excises the membrane and unbinds the adhesions between intestinal segments[7,10]. However, this process requires great care, due to the general possibility of secondary damage, as there are extensive adhesions between the membrane and between the intestinal segments. Bowel perforation, enterocutaneous fistula or sepsis occurring as a result of secondary damage, are among the complications that can be encountered during the postoperative period[3]. The recurrence of the cocoon in the postoperative period is rare but the most probable complication is the obstruction of small intestine due to adhesions. The current case revealed clinical signs of ileus during postoperative day 3 that responded to medical therapy.

In conclusion, abdominal cocoon syndrome is a rarely seen condition, for which the preoperative diagnosis is difficult. The combination of physical examination and radiological signs, and the knowledge of “recurrent characteristics of the complaints” which can be learned by a careful history, may be helpful in diagnosis. It should be remembered that medical treatment will not be beneficial and definitive treatment requires careful surgical excision during the early stages of the disease.

Patient was referred to the emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting for two days.

Upon physical examination, there was asymmetrical distension and general tenderness, especially prominent in upper regions of the abdomen, with heightened intestinal sounds.

The abdominal computerized tomography examination detected dilated small intestinal loops containing air-fluid levels clustered in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and surrounded by a thick, saclike, contrast-enhanced membrane.

During exploratory surgery, widespread adhesions with the peritoneum and small intestine could not be seen.

Please summarize imaging methods and major findings in one sentence.

When the capsule was opened, the small intestinal segments inside the capsule were dilated due to obstruction but otherwise normal in structure.

The operation was completed after total excision of the capsule and removal of the adhesions.

Early diagnosis is important.

It should be remembered that medical treatment will not be beneficial and definitive treatment requires careful surgical excision during the early stages of the disease.

The case report and the discussion are well-written.

P- Reviewer: Hedgire SS, Prasad KK, Paraskevas KI S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Foo KT, Ng KC, Rauff A, Foong WC, Sinniah R. Unusual small intestinal obstruction in adolescent girls: the abdominal cocoon. Br J Surg. 1978;65:427-430. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hur J, Kim KW, Park MS, Yu JS. Abdominal cocoon: preoperative diagnostic clues from radiologic imaging with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:639-641. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Meshikhes AW, Bojal S. A rare cause of small bowel obstruction: Abdominal cocoon. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:272-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Akbulut S, Yagmur Y, Babur M. Coexistence of abdominal cocoon, intestinal perforation and incarcerated Meckel’s diverticulum in an inguinal hernia: A troublesome condition. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;6:51-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li N, Zhu W, Li Y, Gong J, Gu L, Li M, Cao L, Li J. Surgical treatment and perioperative management of idiopathic abdominal cocoon: single-center review of 65 cases. World J Surg. 2014;38:1860-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Singh B, Gupta S. Abdominal cocoon: a case series. Int J Surg. 2013;11:325-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yeniay L, Karaca CA, Calışkan C, Fırat O, Ersin SM, Akgün E. Abdominal cocoon syndrome as a rare cause of mechanical bowel obstruction: report of two cases. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2011;17:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Naidoo K, Mewa Kinoo S, Singh B. Small Bowel Injury in Peritoneal Encapsulation following Penetrating Abdominal Trauma. Case Rep Surg. 2013;2013:379464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kayastha K, Mirza B. Abdominal cocoon simulating acute appendicitis. APSP J Case Rep. 2012;3:8. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Hu D, Wang R, Xiong T, Zhang HW. Successful delivery after IVF-ET in an abdominal cocoon patient: case report and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:994-997. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Wei B, Wei HB, Guo WP, Zheng ZH, Huang Y, Hu BG, Huang JL. Diagnosis and treatment of abdominal cocoon: a report of 24 cases. Am J Surg. 2009;198:348-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |