Published online Nov 16, 2014. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.724

Revised: June 27, 2014

Accepted: October 1, 2014

Published online: November 16, 2014

Processing time: 221 Days and 10.4 Hours

In the last years, operative laparoscopy became a standard approach in gynaecology and general surgery. Even in pregnancy its use is becoming more widely accepted. In fact, it offers advantages similar to those in no pregnant women, associated with good maternal and fetal outcomes. Around 0.2% of pregnant women require abdominal surgery. The most common indications of laparoscopy in pregnancy are cholelithiasis complications, appendicitis, persistent ovarian cyst and adnexal torsion. Authors describe a very rare case of acute abdomen due to isolated Fallopian tube torsion in a 24th weeks pregnant woman, managed by laparoscopic salpingectomy.

Core tip: Authors describe a very rare case of acute abdomen due to isolated Fallopian tube torsion in a 24th weeks pregnant woman, managed by laparoscopic salpingectomy. In all literature the most recent estimation for its incidence dates from 1970, when Hansen estimated 1 per 1.5 million women to have isolated Fallopian tube torsion in Denmark. And since 1933 only 25 cases of Fallopian tube torsion in pregnant women were described.

- Citation: Sidiropoulou Z, Setúbal A. Acute abdomen in pregnancy due to isolated Fallopian tube torsion: The laparoscopic treatment of a rare case. World J Clin Cases 2014; 2(11): 724-727

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v2/i11/724.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v2.i11.724

The Fallopian tube torsion is a rare cause of acute abdomen and even more rare during pregnancy. In 1933, Regad )[1] reported 201 cases of tubal torsion, 12% of these occurred in pregnant women (n = 24). Since 1933 until 2013 only 25 cases were described.

The etiology is uncertain, but some authors described factors that could be implicated in the occurrence of Fallopian tube torsion. Some of them are intrinsic of the tube like congenital anomalies or acquired pathology (hidrosalpinx, hematosalpinx, neoplasm, surgery) or autonomic dysfunction and abnormal peristalsis; and other are extrinsic like adhesions, pregnancy, mechanical factors, movement or trauma to the pelvic organs or pelvic congestion[2,3].

Since the Fallopian tube torsion is a rare condition and sporadic cases are reported, its real incidence is unknown, and it seems that it is more frequent in the reproductive age, which is understandable because almost all risk factors are not frequent before menarche or during menopause[3].

The clinical characteristics, the laboratory or the imaging studies are not specific, so the diagnosis is difficult. The acute abdominal pain at the lower quadrants is the most common symptom, with sensitive painful palpation of the same abdominal area. As the clinical and the complementary study are not specific, the definitive diagnosis can be made by laparoscopy. The authors think that, at the present time, laparoscopy in the setting of experienced and dedicated teams should be the standard approach for this situation, even in pregnant women.

We described a case of a 24 wk pregnancy with a right Fallopian tube torsion which was managed by laparoscopic salpingectomy.

A 36-year-old healthy primigravida, with an uneventful pregnancy until the 24th week of pregnancy. At this time she complained of a persistent right flank abdominal pain with a sudden increase. Physical examination revealed abdominal enlargement compatible with pregnancy age and a painful right mid abdominal quadrant palpation, with tenderness and without palpable masses.

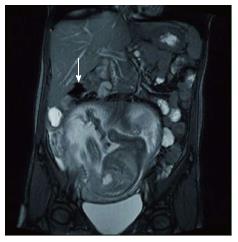

The ultrasound study revealed a single, life fetus, with a biometry compatible to a 24 wk pregnancy, with normal amniotic fluid volume and with a normal placenta with no signs of abruption; and in the right lower area it showed a cystic structure measuring 4 cm × 3 cm in diameter, probably with an adnexial origin. The MRI confirmed the cystic image, without anyother pathology (Figure 1). Because pain persists, laboratory findings were unspecific and physical examination then was a persisting pain with poor tenderness and peritoneal reaction (acute abdominal pain), two diagnoses were made - acute appendicitis and adnexal torsion.

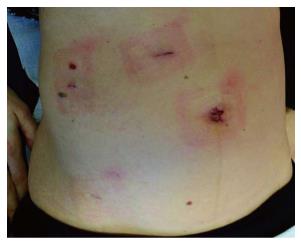

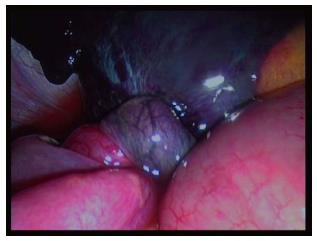

A diagnostic laparoscopy was then performed. Because the uterus extends 5 cm above the umbilicus, this fact limits the abdomen first entrance, so a direct entrance in the umbilicus could accidental damage the uterus. Alternative Palmer point or the 9th intercostal space is also dangerous because the big pregnant uterus push all the abdominal viscera up. The surgery that we described was an emergent situation, the bowel was not prepared, the viscera distortion was bigger. So the decision was to perform the open technique with the Hasson trocar. The problem was identified by the diagnostic laparoscopy and then the auxiliary trocars were placed underdirect vision and according to the best ergonomic approach for the salpingectomy (Figure 2). We decided to perform a salpingectomy because of the gangrenous aspect of the tube as consequence of its pedicle torsion (Figure 3), without any macroscopic changes of the appendix. The specimen was extracted with a laparoscopic bag. The patient was discharged on the second day after surgery without any complains or surgical and obstetric complication. The reason for two days of hospital stay was based on the diagnosis in a 24th week pregnant woman and immediate control of fetal well-being.

The histopathologic examination of the specimen showed a necrotic tube, secondary of a paraovarian cyst torsion. She delivery a healthy, 3350 g, baby at the 40th week of pregnancy by an instrumental vaccum vaginal delivery because of a progressive distocia at the 2nd stage. No maternal or fetal complications occurred at the peripartum period.

Isolated torsion of Fallopian tube is a very uncommon condition, even more rare in pregnant women. In all literature the most recent estimation for its incidence dates from 1970, when Hansen[4] estimated 1 per 1.5 million women to have isolated Fallopian tube torsion in Denmark. And since 1933 only 25 cases of Fallopian tube torsion in pregnant women were Described[2,5,6]. Since this is a very rare situation, probably the series published underestimate the real incidence of this pathology.

Other aspect hard to describe is its etiology. Its real cause is uncertain and it can happen in healthy tubes, but some risk factors were described as possible causes. This factors were divided in two types: internal or intrinsic like congenital anomalies (excessive length of tube or spiral course), acquired pathology (hidrosalpinx, hematosalpinx, neoplasm, surgery) or autonomic dysfunction and abnormal peristalsis; and external or extrinsic factors such as changes in neighboring organs (neoplasm, adhesions, pregnancy), mechanical factors, movement or trauma to the pelvic organs or pelvic congestion[2,3,7].

Although the clinical characteristics are not exclusive of the Fallopian tube torsion, the most common symptom is the lower abdominal pain, generally with a sudden onset and accompanied by nausea, vomiting or urinary urgency[2,3]. Physical findings include abdominal tenderness, with or without peritoneal signs and an inconstant palpable mass[2,3].

All this clinical signs and symptoms are common with other medical conditions and give the physician a differential diagnosis problem, which includes ovarian torsion, acute appendicitis, ectopic pregnancy, acute salpingitis, tuboovarian abscess, ruptured ovarian cyst, degenerated leiomyoma, urolithiasis, intestinal obstruction or perforation[7-9]. Laboratory values are nonspecific and do not help in the differential diagnosis[7,9]. The sonographic findings of isolated Fallopian tube torsion are not pathognomonic and are quite variable[9], especially in second and third trimesters of pregnancy, where the adnexas are more difficult to visualize. But the finding of a high impedance or absence of flow in a tubular structure, especially in a patient with a history of tubal ligation, can be indicative of the diagnosis[10,11].

Pre-operative diagnosis of tubal torsion is very difficult and as its management is surgical the diagnostic laparoscopy is the tool for the definitive diagnosis and treatment[3], even in advanced pregnancies, like the case described.

Until now, there are no prospective and randomized studies that compared laparoscopic procedures with laparotomy during pregnancy. Retrospective studies published, show that laparoscopy in pregnancy appears safe and can be performed without a considerable increment in maternal and fetal complications. Mathevet et al[12] published the results of 48 laparoscopic procedures for management of adnexal masses in pregnancy (17 cases were performed during the first trimester, 27 cases in the second trimester and 4 in the third trimester). Except one fetal loss 4 d after surgery, no complications were observed during the intra and post-operative periods and obstetrical outcomes were. So the authors concluded that laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnancy is a safe and effective procedure, performed by an experienced team. Similar conclusions were made by Lenglet et al[13] in a series of 26 pregnant patients who underwent the laparoscopic surgery of ovarian cysts.

Despite the limited data, it seems that laparoscopic surgery in pregnancy, in experienced hands, is a technique acceptable with some advantages, including early return of bowel function, early ambulation, short hospital stay, rapid return to normal activity, low rate of wound infection and hernia and less pain after the procedure[14,15]. Another advantage of laparoscopy is the lesser manipulation of the uterus which leads to less uterine contractions, so less spontaneous abortion, preterm labor and premature delivery[14]. However laparoscopy during pregnancy should be performed with caution and some precautions should be taken like: routinely intraoperative fetal monitoring, attention with patient position (for example, the lateral decubitus position should be preferred to prevent inferior vena cava compression), the Hasson trocar open technique seems to be safer to prevent inadvertent puncture of the uterus (but no studies showed a real advantage under the Veress technique), intra-abdominal pressure should be kept less than 15 mmHg, maternal end- tidal volume CO2 should be monitored and kept within the normal range, depending on the height of the uterus the secondary trocars should be inserted under direct vision and their position decided according to the uterus size and the position of the abnormal findings. The administration of prophylactic tocolytics is not necessary; it can be given if there is evidence of uterine contractions[14,16].

In conclusion, isolated Fallopian tube torsion should be considered as a possible diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in pregnancy. The diagnostic laparoscopy is the gold standard for its definitive diagnosis and allows the tube torsion resolution with a minimal invasive technique, even in pregnant women.

Acute abdómen in pregnancy, diagnostic challenges.

Abdominal enlargement compatible with pregnancy age and a painful right mid abdominal quadrant palpation, with tenderness and without palpable masses.

Laboratory and image exams, high clinical suspicion.

Ultrasonnography in first approach, magnetic resonance imaging confirmation.

Histology validates the findings.

Laparoscopy, diagnostic and treatment.

Laparoscopy in experienced hands might be the gold standard approach in acute abdómen in pregnant woman.

In this case report, the authors highlighted the useful of laparoscopic approach for emergent abdominal surgery in pregnant women. Their assertion is acceptable and the manuscript is well written.

P- Reviewer: Agresta F, Noguera J, Yokoyama N S- Editor: Song XX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ

| 1. | Regad J. Etude anatomo-pathologique de la torsion des trompets uterines. Gynecol Obstet. 1933;27:519-35. |

| 2. | Origoni M, Cavoretto P, Conti E, Ferrari A. Isolated tubal torsion in pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;146:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krissi H, Shalev J, Bar-Hava I, Langer R, Herman A, Kaplan B. Fallopian tube torsion: laparoscopic evaluation and treatment of a rare gynecological entity. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2001;14:274-277. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hansen OH. Isolated torsion of the Fallopian tube. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1970;49:3-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Işçi H, Güdücü N, Gönenç G, Basgul AY. Isolated tubal torsion in pregnancy--a rare case. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2011;38:272-273. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Duncan RP, Shah MM. Laparoscopic salpingectomy for isolated fallopian tube torsion in the third trimester. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2012;2012:239352. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Antoniou N, Varras M, Akrivis C, Kitsiou E, Stefanaki S, Salamalekis E. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2004;31:235-238. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Yalcin OT, Hassa H, Zeytinoglu S, Isiksoy S. Isolated torsion of fallopian tube during pregnancy; report of two cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1997;74:179-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Batukan C, Ozgun MT, Turkyilmaz C, Tayyar M. Isolated torsion of the fallopian tube during pregnancy: a case report. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:745-747. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Baumgartel PB, Fleischer AC, Cullinan JA, Bluth RF. Color Doppler sonography of tubal torsion. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1996;7:367-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Elchalal U, Caspi B, Schachter M, Borenstein R. Isolated tubal torsion: clinical and ultrasonographic correlation. J Ultrasound Med. 1993;12:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Mathevet P, Nessah K, Dargent D, Mellier G. Laparoscopic management of adnexal masses in pregnancy: a case series. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2003;108:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lenglet Y, Roman H, Rabishong B, Bourdel N, Bonnin M, Bolandard F, Duband P, Pouly JL, Mage G, Canis M. [Laparoscopic management of ovarian cysts during pregnancy]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2006;34:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Al-Fozan H, Tulandi T. Safety and risks of laparoscopy in pregnancy. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;14:375-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Fatum M, Rojansky N. Laparoscopic surgery during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:50-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kilpatrick CC, Orejuela FJ. Management of the acute abdomen in pregnancy: a review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:534-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |