INTRODUCTION

Anterior glenohumeral dislocation during sports activities or social life is one of the most commonly seen pathologies in the clinical practice of orthopedic traumatology. The prevalence of anterior glenohumeral instability has been reported as 2%[1]. The glenohumeral joint has been reported as the most commonly dislocated synovial joint of the human body[2]. Forced abduction and external rotation of the shoulder can cause anterior dislocation resulting in instability[3]. Participation in athletics can place exceptional demands on the musculoskeletal system, especially the shoulders of the ones who perform overhead activities[4]. Shoulder instability most commonly affects people who are in their late teens to mid-thirties[5]. A major problem following a primary traumatic anterior shoulder dislocation is the high risk of recurrence among young patients[6]. Rhee et al[7] mentioned that these injuries occur at a younger age, with higher rates of recurrence, and with shorter intervals between initial injury and recurrent instability events among athletes. Because of increasing participation of people from any age group of the population in sports activities, health care professionals dealing with the care of trauma patients must have a thorough understanding of the anatomy, patho-physiology, risk factors, and management of anterior shoulder instability. Degenerative arthropathy in the shoulder joint is generally the final result of chronic instability[8]. The purpose of this review article is to discuss the clinical spectrum of recurrent traumatic anterior shoulder instability with the current concepts and controversies at the scientific level.

FUNCTIONAL ANATOMY

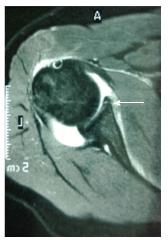

Shoulder joint is a complex anatomical and biomechanical structure which functions in a manner that several stabilizers play role in a special harmony in different stages of motion. Stability of the shoulder is established by the glenohumeral articulation, labrum, glenohumeral ligaments, rotator cuff, and deltoid muscle. The contact surface of the humeral head with the glenoid is about 30%, which means that the joint has a limited osseous constraint so that the primary stability is due to other soft tissue components rather than the osseous contact[9]. This allows a very large range of motion but in turn, a predisposition to subluxation or dislocation as well. The anterior labrum plays a key role in anteroposterior stability as it deepens the glenoid cavity up to 50%[10]. Therefore, injuries causing detachment of the labrum from its original anatomic location can cause recurrent anterior instability. A Bankart lesion, which is defined as the anteroinferior detachment of the glenoid labrum, was demonstrated in 87% to 100% of first-time dislocations[11-13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1 The Bankart lesion on magnetic resonance imaging.

The superior, middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments unite to form a soft tissue complex which functions as a static stabilizer for the joint. Each component of this ligamentous structure has its unique contribution to joint stability during different stages of motion. The coracohumeral ligament also functions synergistically with the superior glenohumeral ligament in resisting inferior translation of an adducted shoulder joint[14]. The middle and inferior glenohumeral ligaments provide anterior stability in different degrees of shoulder abduction and external rotation. The anteroinferior portion is the weakest part of the glenohumeral ligament complex in an abducted and externally rotated shoulder.

The deltoid muscle and the rotator cuff are named as the primary dynamic stabilizers which are active during shoulder motion in all axes[9]. The pathologies affecting the deltoid muscle and the rotator cuff not only cause decrease in range of motion of the shoulder joint but also disturbance of the biomechanical stability. Muscle weakness and/or imbalance of the dynamic stabilizers have been reported as leading to recurrent anterior shoulder instability[15-20].

CLINICAL EVALUATION

A detailed history and a careful physical examination of the patient are the primary steps of the clinical assessment. Mechanism of the first incident, time period from the first dislocation to recurrent instability, activities leading to recurrence or apprehension, number of dislocations, and history of reducibility without emergency visit should be noted for each patient. Schrumpf et al[14] mentioned the importance of distinguishing traumatic subluxation or dislocation and multidirectional instability, as the pathophysiologies and the treatment approaches of them were far different.

Physical examination is crucial in understanding the mechanism of recurrent dislocations. Comparative evaluation of both shoulders should be performed. Any visible deformity and/or muscle atrophy with respect to contralateral shoulder, or any scar tissue related to past trauma or surgery are important and simply recognizable just by a careful inspection. Active and passive range of motion in all planes should be measured and noted for both shoulders in every patient. Generalized ligamentous laxity should be kept in mind and checked in every patient. Axillary nerve examination should always be considered as critically important during clinical assessment. Apprehension and relocation tests as provocative examination are the fundamentals of clinical evaluation of any patient with a medical history of recurrent instability (Figure 2). Anterior apprehension test is performed with the shoulder in 90 degrees of abduction and the elbow in 90 degrees of flexion, with forced external rotation applied to the extremity as anterior stress is applied to the humerus. Relocation test is performed while the patient is supine and the shoulder in 90 degrees of abduction and external rotation. Anterior stress is applied to the humerus in various degrees of abduction. When the pain or apprehension occurs, posterior-directed force is applied to relocate the humeral head. If the release of posteriorly directed stress used to relocate the humeral head produces a feeling of apprehension or subluxation, it indicates anterior instability. Laxity specific to lesions of inferior glenohumeral ligament can be distinguished by performing the hyperabduction test (Gagey’s sign)[21].

Figure 2 Apprehension and relocation tests.

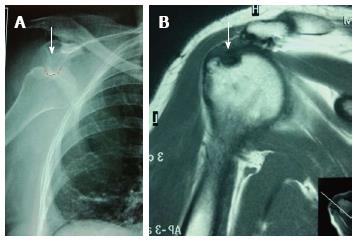

Anteroposterior, axillary lateral and scapular Y-view images are the primary routine radiographic evaluation tools in patients with recurrent instability (Figure 3). Different specific radiographic imaging techniques including apical oblique view, West point axillary view or Stryker notch view can also be valuable to detect particular pathologies related to patient’s complaint. West point axillary view is used to evaluate for a glenoid rim fracture, whereas Stryker notch view is for Hill-Sachs lesion. However, a three-dimensional computed tomography is gold-standard technique to detect osseous pathologies as well as quantifying the degree of bone loss[22]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a very useful tool in detecting soft tissue pathologies. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI is a minimally invasive and effective radiographic method to diagnose any capsular or labral damage pre-operatively.

Figure 3 Anteroposterior shoulder view and scapular Y view radiographs.

RISK FACTORS FOR RECURRENT INSTABILITY

Many different risk factors for recurrent anterior shoulder dislocation such as young age, participation in high demand contact sports activities, previous history of ipsilateral traumatic dislocation, presence of Hill-Sachs or osseous Bankart lesion, ipsilateral rotator cuff or deltoid muscle insufficiency, and underlying ligamentous laxity have been described[1,23-30]. Ramsey et al[31] reported that traumatic anterior instability of the shoulder is associated with a high rate of recurrence in young patients. Marans et al[32] reported 100% redislocation rate in twenty-one skeletally immature patients who were treated with a sling.

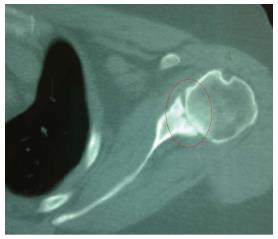

According to Porcellini et al[33], age at the time of the first dislocation, male sex, and the time from the first dislocation until surgery were significant risk factors for recurrence. However, in a prospective multicenter clinical study with twenty-five years of follow-up no significant differences with respect to gender could be demonstrated[34]. According to the results of a Level-I prospective cohort study subjects with a prior history of glenohumeral joint instability were approximately five times more likely to experience a subsequent instability event, regardless of direction[35]. Although glenoid bone loss is more common, engaging Hill-Sachs lesions can also be a cause of recurrent instability[36] (Figure 4). A Hill-Sachs lesion, which is defined as an osseous defect resulting from forceful impaction on the posterolateral side of the humeral head during anterior dislocation, was demonstrated as high as 90% to 100% of the patients with shoulder instability[11-13]. Hovelius et al[34] reported that immobilization was not found to be associated with the risk of re-dislocation.

Figure 4 Engaging Hill-Sachs lesion leading to recurrent anterior instability (A) and Hill-Sachs lesion on magnetic resonance imaging (B).

TREATMENT

Recurrent anterior shoulder instability resulted from an initial traumatic dislocation can be as serious as preventing an athlete from returning to sports. Without proper treatment, chronic instability generally results in a degenerative arthropathy in the shoulder joint (Figure 5). The common surgical interventions address the labral tears as well as the capsular laxity which are generally the basic underlying pathologies. Surgical repair of any accompanying rotator cuff tear should also be included in the treatment process (Figure 6). Although many different surgical techniques have been described to treat traumatic recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder, the best method still remains controversial. A successful clinical outcome basically requires an accurate surgical technique applied via adequate exposure. The main objective of the treatment should be considered as the most anatomical repair of the well defined pathological condition leading to recurrent instability. Achieving the best result for any particular patient depends on the procedure which allows observation of the joint surfaces, provides the anatomical repair, maintains range of motion, and also can be applied with low rates of complications and recurrence.

Figure 5 Degenerative arthritis secondary to chronic instability.

Figure 6 Rotator-cuff tear in a patient with recurrent anterior instability.

Open and arthroscopic procedures are treatment options in patients with traumatic recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder which is unresponsive to conservative measures. The arthroscopic treatment of glenohumeral instability requires that a level of expertise be achieved and retained[31]. Although open stabilization was reported as more effective than arthroscopic stabilization in the aspect of post-operative recurrence rates in 1990s, clinical outcomes have become similar in time. Technological improvements in arthroscopic instrumentation as well as the development of the innovative surgical techniques as a result of the cumulative experience with improved understanding of the factors leading failure in such patients have played the key role[24,33,37-43]. In their prospective randomized study, Fabbriciani et al[41] reported equal results between arthroscopic and open surgical repair of Bankart lesion in the aspect of recurrence. According to the results of another recent prospective randomized clinical trial comparing open and arthroscopic techniques, the difference in quality of life between the patients in the two groups was neither significant nor clinically important at two years follow-up; however significantly lower risk of recurrence was obtained in patients for whom open repair was preferred[5]. Surgical treatment of athletes participating in contact sports is still controversial. Rhee et al[44] compared the results of arthroscopic and open stabilization in young contact athletes and reported recurrent instability as 25% in the arthroscopic group and 13% in the open stabilization group. Some authors mentioned that athletic activity plays a greater role in post-operative recurrence than the surgical method used for stabilization[39,45].

Bone loss either on the glenoid or the humeral head may cause or complicate recurrent shoulder dislocations. Recurrent episodes of anterior instability of the shoulder joint may cause Hill-Sachs or osseous Bankart lesion get larger which leads further instability[46,47]. Therefore, isolated Bankart repair is generally not sufficient as the surgical management of the patients with osseous lesions. In their study which evaluates the morphology of the glenoid cavity in patients with recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder, Sugaya et al[48] concluded that 10% of subjects did not have osseous pathology, 40% had bony erosion, and 50% had an osseous Bankart lesion. If bone loss is greater than 25% of the glenoid surface, surgical treatment should include a bony reconstruction procedure[49]. Ideal technique for the surgical management of bony defects on the glenoid rim is controversial. Reduction and fixation of the displaced glenoid rim fracture, transfer of the coracoid process to the anterior glenoid, and reconstruction by using autograft or allograft bone block are the methods to restore the normal width and depth of the glenoid cavity. Basically, all of the various surgical interventions aim to restore more anatomic glenoid morphology to prevent recurrent instability. Park et al[50] reported that following successful fixation of the glenoid fracture in its anatomic position, fragments unite and survive without resorption at one year. When the bone loss is greater than 25% of the glenoid surface with a missing fragment, transfer of the coracoid process to the anterior glenoid rim as a structural block is the best approach. Bristow, Latarjet, or Trillat procedures are effective, most widely known and used techniques of coracoid transfer into the glenoid lesion. Latarjet procedure, which was first described in 1954, is the transfer of the coracoid process through the subscapularis tendon to provide an osseous block during joint motion. Bristow procedure is the technique in which the terminal 1 cm of the coracoid is transferred together with the conjoint tendon onto the neck of the scapula through a horizontal slit in the subscapularis muscle. In Trillat procedure, the coracoid is osteotomized following an arthrotomy, then it is displaced and fixed with a coracoscapular screw. Burkhart et al[51] reported that no recurrent instability was detected at a mean follow-up of 4.9 years following coracoid transfer performed in forty-seven patients. The Latarjet procedure, also as a revision to manage recurrence of anterior shoulder instability after previous operative repair associated with defects of the anterior glenoid rim and an intact subscapularis muscle, was reported as satisfactorily restoring glenohumeral stability[52]. Warner et al[53] and Scheibel et al[54] evaluated recurrence of the anterior instability following anterior glenoid augmentation by using iliac crest bone autograft and they reported no evidence of recurrent instability in their series.

Burkhart et al[24] used the term “engaging Hill-Sachs lesion” to describe a compression fracture on the posterosuperior aspect of the humeral head which drops over the glenoid rim in external rotation of an abducted shoulder and is associated with recurrent instability. Tenodesis of the infraspinatus into the lesion which is also called “remplissage” and bone grafting of the defect are the surgical interventions described to address the osseous defect on the humeral head. Boileau et al[55] reported that arthroscopic Hill-Sachs remplissage procedure in combination with Bankart repair in the treatment of patients with a large bony defect on the humeral head was an effective method. The authors also concluded that 98% of the patients had a stable shoulder joint at the latest follow-up with approximately 10 degrees of restriction in external rotation which did not significantly affect return to sports activity. An in-vitro study evaluating biomechanical effects of remplissage showed that in specimens with a 30% Hill-Sachs lesion it prevented engagement of the lesion[56]. Bone grafting can also be applied as another treatment option for defects of the humeral head. Osteoarticular plugs and osteoarticular humeral head allograft are the options for large diameter lesions[36,57]. Collapse or resorption of the graft should be kept in mind as an important risk factor which may lead to failure in such cases.

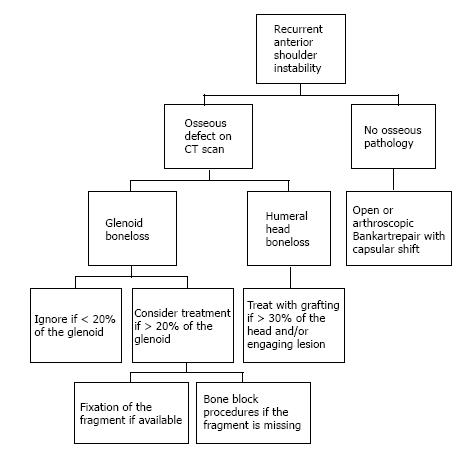

There are various techniques addressing different pathologies of both the soft tissues and bones which generally unite to form a complex disease process. Therefore, when dealing with the clinical management of recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder joint, one should always carefully analyze the patient-specific pathologies and consider treatment options according to the needs of every particular case. In this regard, a guideline is generally needed. Figure 7 demonstrates the algorithm that we use in the management of patients with recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder joint.

Figure 7 Treatment algorithm that we follow in our clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

Anterior shoulder instability is among the most commonly seen disorders in traumatology, which typically affects the younger age population with high rates of recurrence. Recurrent anterior instability of the shoulder is a complex disease which may include both soft tissue and osseous pathologies. Primary clinical approach should be the combination of a careful medical history, a detailed physical examination, and appropriate imaging studies to recognize changes leading to recurrence. Although various surgical techniques have been described, a consensus does not exist and thus, surgeons should select the most effective procedure to restore joint stability in a patient-specific manner.

P- Reviewer: Ertem K, Swanik C S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Lu YJ